Introduction

Regional anesthetic blocks constitute an integral component of a multimodal pain management strategy, frequently employed within emergency departments and perioperative clinical contexts. Preoperatively, such blocks find utility across a diverse spectrum of surgical procedures. In emergency department scenarios, their application facilitates procedures like inserting internal jugular central venous catheters, treating clavicular fractures, wound repair, and drainage of abscesses involving the earlobe and submandibular areas. The superficial cervical plexus block (CPB), in particular, confers ipsilateral anesthesia encompassing the anatomical region colloquially referred to as the "cape." This region delineates its boundaries by the posterior tip of the earlobe, the clavicle's lateral extremity, the mandible's medial aspect, and the clavicle's inferior surface.[1]

Remarkably, CPBs are characterized by their ease of administration and proficiency in conferring anesthesia within the distribution spanning C2 to C4. This includes their applicability in procedures such as carotid endarterectomies, lymph node dissection, and plastic surgery.[2][3] Furthermore, the superficial CPB can be judiciously combined with the deep CPB to furnish comprehensive regional anesthesia, notably within the realm of oral and maxillofacial surgery.[4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The superficial cervical plexus originates from the ventral rami of nerve roots C2 to C4. These nerve roots contribute to the sensory innervation of the skin and superficial structures of regions such as the auricle of the ear, acromioclavicular joint, clavicle, and anterolateral neck.[1] Notably, these branches emerge at a midpoint along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), precisely at the level corresponding to the thyroid cartilage notch. Converging from these roots, the plexus forms 4 terminal branches: the lesser occipital, greater auricular, transverse cervical, and supraclavicular nerves, all exiting from behind the posterior border of the SCM. While it is often possible to visualize the plexus as a collection of hypoechoic oval structures situated deep or lateral to the posterior border of the SCM, this presentation may not always be evident. The primary objective of this block is to facilitate the precise deposition of a local anesthetic near the sensory branches arising from nerve roots C2, C3, and C4. This task is particularly challenging because the SCM forms a protective "roof" over these nerve roots.

Deep Cervical Plexus Block

The following are the 3 landmarks identified to perform a deep CPB:

- Mastoid process

- Chassaignac tubercle (the transverse process of the sixth cervical vertebra)

- The posterior border of the SCM

To estimate the line of needle insertion that overlies the transverse processes, the mastoid process (MP) and the Chassaignac tubercle, the transverse process of the sixth cervical vertebra (C6), are identified and marked (see Image. Mastoid Process). The transverse process of C6 is usually easily palpated behind the clavicular head of the SCM at the level just below the cricoid cartilage. Next, a line is drawn connecting the MP to the Chassaignac tubercle. Once this line is drawn, label the insertion sites over the C2, C3, and C4 transverse processes located on the MP–C6 line 2 cm, 4 cm, and 6 cm, respectively, caudal to the mastoid process.

Superficial Cervical Plexus Block

A line extending from the MP to C6 is drawn as described above. The site of needle insertion is marked at the midpoint of this line. This is where the branches of the superficial cervical plexus emerge from behind the posterior border of the SCM (see Image. Cervical Plexus Block Probe Placement).

Indications

The CPB is pivotal in delivering anesthesia and analgesia to the head and neck region, with its application contingent upon the specific surgical context. The CPB encompasses distinct depths, eg, deep, intermediate, and superficial, each catering to various branches of the cervical plexus. Depending on the surgical procedure, the plexus can be targeted at either a superficial or deep level or occasionally both. The superficial branches of the plexus are responsible for innervating the skin and superficial structures of the head, neck, and shoulder. In contrast, the deep branches extend their innervation to the muscles in the deep anterior neck and even the diaphragm.

A superficial CPB is indicated when there is a need for dense anesthesia and analgesia to the skin and underlying anatomy of the anterolateral neck (see Image. Superficial Cervical Plexus Block Anesthetic Area). In addition to the anterolateral neck, anesthesia is achieved in the superficial structures of the ear, clavicle, and acromioclavicular joint.[5] Common superficial CPB indications include carotid endarterectomies, lymph node dissections, and superficial neck surgeries. The versatility of the CPB is further exemplified by its safe utilization in emergency departments for addressing soft tissue and bony injuries, encompassing injuries to the ear, neck, and clavicular region, including conditions like clavicular fractures and acromioclavicular dislocations.[1] While no other published studies are available, a single case series showed this block to be successfully used in pediatric patients requiring internal jugular venous placement for emergent dialysis.[6] Another study showed that using a superficial CPB for anesthesia during anterior cervical discectomy and fusion enhanced recovery outcomes without significantly impacting overall opioid consumption or discharge times.[7]

The deep CPB specifically targets adjacent levels along the cervical spine and finds utility in more profound head and neck surgical interventions, including vocal cord surgeries, dental abscess procedures, lymph node dissections, and plastic repairs. Recent developments have extended the application of deep CPB to managing cervicogenic headaches, offering a diagnostic tool to distinguish them from migraines.[8]

Furthermore, CPBs can complement the interscalene approach to the brachial plexus, mainly when large volumes are used for shoulder surgery, serving as an advantageous addition for shoulder surgery patients. In cases where supra- or infra-clavicular approaches are preferred to circumvent phrenic nerve block, these approaches can be supplemented with a superficial CPB to ensure comprehensive analgesia for shoulder surgeries.

Bilateral superficial blocks can be harnessed effectively for certain surgical scenarios like thyroid and parathyroid surgeries. These blocks have even been employed as sole anesthetics for high-risk patients under monitored anesthesia care (MAC) and for postoperative analgesia. Nevertheless, it's worth noting that unilateral superficial cervical blocks are sometimes underutilized despite their capacity to provide anesthesia not only to the neck but also to the subcutaneous tissue over the clavicle, mediated by the supraclavicular nerves. This block has proven valuable for central venous cannulation via the internal jugular or subclavian routes.

Contraindications

Contraindications for superficial CPB include:

- Patient refusal

- Active infection overlying the injection site

- Contralateral phrenic nerve paralysis

- Previous neck surgery

- Neck radiation

- Allergy to amide and ester local anesthetic agents [5]

Caution must be exercised in patients who have severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or an untreated contralateral pneumothorax, as this block has the potential for accidental phrenic nerve dysfunction. However, a prospective randomized study has recently challenged this potential complication.[9]

Equipment

The equipment needed to perform a CPB include:

- Sterile towels

- Sterile 4 × 4 inches gauze pads

- Sterile gloves

- High-frequency (6-13 Hz) linear ultrasound probe, ultrasound gel, and sterile probe cover

- Chlorhexidine or iodine-based solution for skin preparation

- Local anesthetic with the appropriate duration of action, eg, shorter-acting agents like lidocaine for laceration repairs and longer-acting agents like ropivacaine for clavicular fractures

- 25 gauge 1.5-inch needle for the block

- 10 mL to 20 mL syringe

- Low-volume extension tubing

Personnel

Personnel necessary to perform a CPB include:

- Clinician performing procedure

- Assistant can be used but is not necessary

- Nurse to monitor patient vitals and comfort as well as retrieve any needed supplies

Preparation

Certain standard precautions are typically taken when preparing for a CPB. The patient must be fully informed about the procedure, and written or verbal consent may be required depending on institutional policy. The clinician, primary nurse, and pharmacist should know how to identify and treat local anesthetic systemic toxicity.[10] Ensuring the injection site is entirely free of any signs of infection and cleaned with an antiseptic solution is crucial. Additionally, sterile gloves must be worn, the probe surface must be covered with a sterile cover, and sterile ultrasound gel must be applied over the probe contact site.

Technique or Treatment

When using CPBs in clinical practice, considering individual patient factors, potential complications, and proper technique selection is essential.[11]

Patient Positioning

The patient can be placed into 1 of the following positions: supine or semi-sitting, both with head turned to the contralateral side, or lateral decubitus. The lateral decubitus position allows the ultrasound to be placed across from the patient for optimal ergonomics and viewing of the display screen. The patient's comfort and limitations must be taken into consideration during positioning. In patients who are obese, the posterior border of the SCM can be challenging to identify. The patient can lift their head off the bed to facilitate palpation of the posterior border of the SCM.

Use of Ultrasound

Using ultrasound guidance offers many advantages, including visualizing vascular structures, real-time visualization of local anesthetic dispersion, and continuous monitoring of needle tip depth. Ultrasound can be confidently used to perform a superficial CPB, but experience with ultrasound-guided deep CPB is still in its infancy and not well described in the literature.[12] Notably, experienced operators have been found to have a similar success rate when using the landmark-based technique only vs an ultrasound-guided approach.[13]

Techniques

Landmark-Based Technique

A line extending from C6 to the MP is drawn along the posterior border of the SCM. The needle insertion is at the midpoint of this line. The branches of the superficial cervical plexus emerge behind the posterior border of the SCM at this point. Skin is prepped and draped in the usual fashion. Employing the "needle fanning" technique involves repeated needle redirections and injecting the local anesthetic along the posterior border of the SCM, both 2 cm below and above the needle insertion site. Caution is advised against deep needle insertion exceeding 1 cm to 2 cm.

Ultrasound-Based Technique

The procedure commences with identifying the relevant anatomy utilizing a high-frequency linear probe. The probe is positioned transversely at the midpoint between the mastoid process and the clavicle, precisely over and slightly posterior to the SCM. An additional common anatomical landmark is the superior aspect of the thyroid cartilage. Before initiating the procedure, ensuring skin disinfection and appropriate draping is imperative.

Once the SCM is visualized, the transducer is carefully moved posteriorly until the lateral edge of the muscle is in view, covering the levator scapulae muscle and, further caudad, the interscalene groove. Particular attention should be devoted to visualizing the local neurovascular anatomy, including the internal jugular vein, external jugular vein, common carotid artery, and the brachial plexus.

The fascial plane delineating the space between the levator scapulae and SCM can then be discerned. Within this striated, hyperechoic substance, a hypoechoic cluster representing the superficial cervical plexus can be visualized, typically located just deep to the posterior surface of the lateral SCM.

With an in-plane technique, the needle is introduced parallel to the ultrasound beam, proceeding from the posterolateral to the medial direction. The needle is advanced through the skin and platysma under real-time ultrasound guidance until it approaches the vicinity of the plexus. Aspiration is performed to ensure the needle tip is not within a vascular structure. Following this, hydrodissection is employed to verify the optimal placement of the anesthetic. Approximately 10 mL of the local anesthetic is administered in roughly 2 mL aliquots to ensure a linear spread across the SCM's deep margin.[1][5]

Complications

Complications may arise while administrating a CPB, with a higher incidence in deep blocks than superficial ones. An adequate understanding of the block's physiology and local anesthetic toxicity can mitigate these issues.[10] Superficial CPB shares common complications with other local anesthetic-based nerve blocks, including intravascular injection into a vein or artery, hematoma formation, infection risk, and local anesthetic toxicity.

In contrast, deep CPB presents more severe complications, notably the inadvertent intravascular injection into the vertebral artery. This artery lies within the vertebral canal, situated approximately 0.5 cm below the tip of the transverse process, the anatomical landmark for local anesthetic deposition during deep CPB. Since the vertebral artery directly supplies blood to the brain, even a minute amount of local anesthetic can lead to central nervous system (CNS) effects as it swiftly reaches the brain. Therefore, maintaining continuous verbal contact with the patient during injection is crucial to promptly detect early signs of CNS toxicity, such as perioral numbness, disorientation, or tinnitus. Frequent aspiration should also be performed. With a slow injection rate and sustained patient communication, the progression of toxicity from the CNS to cardiac manifestations is highly improbable.

Another concerning complication of deep CPB is subdural injection. Placing the needle too far can inadvertently penetrate the dural sleeve surrounding the nerve root, potentially resulting in a subarachnoid block leading to unconsciousness and hypotension. In such cases, endotracheal intubation and respiratory and cardiovascular support may become necessary.

Furthermore, the cervical plexus is closely situated to large vessels (ie, the internal jugular vein and carotid artery) in the neck, and accidental vessel puncture may lead to significant hematoma formation.[5] Early recognition allows for local compression to alleviate the issue; however, in rare instances, when left unaddressed, it can lead to airway compromise. Additionally, unintentional deep injection or excessive local anesthetic volume can cause dysfunction and blockade of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, deep cervical plexus, and brachial plexus.[1] Accidentally blocking the accessory nerve can cause SCM and trapezius muscle weakness; this is also thought to cause phrenic nerve dysfunction, though a recent prospective randomized study found this untrue.[9]

Clinical Significance

The CPB is a valuable option for anesthesia and analgesia in various surgical procedures. CPBs are simple to learn, and their indications are expanding as we know more about the applications of these blocks. Carotid endarterectomy remains the most common indication of a CPB. Other than carotid endarterectomy, there are many other procedures on the neck where this block can be utilized, including procedures like internal jugular venous cannulation, lymph node biopsies, lymph node dissection, plastic surgery, laceration repairs, incision and drainage of abscesses, and thyroid and parathyroid surgeries. The block is also finding its place in the emergency department for simple procedures for soft tissue and bone injuries, such as ear, neck, and clavicular region injuries, including fractures and dislocations. Recently, the use of this block has also been described for cervicogenic headaches.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Administering a CPB requires a multidisciplinary approach involving physicians, nurses, and pharmacists to ensure patient-centered care and optimize outcomes. Clinicians must possess the skills to perform the procedure accurately, adhering to stringent anatomical knowledge and precise techniques. Pharmacists ensure all medications used are not expired and correctly dosed. Nurses care for the patient before, during, and after the procedure, ensuring patient comfort and stability. Ethical considerations come into play when determining patient suitability for the block, weighing potential risks and benefits, and obtaining informed consent.

Interprofessional communication between the clinician and the nurse is essential for comprehensive patient assessment, pre-procedural planning, and post-procedure monitoring, fostering a shared understanding of the patient's condition. Care coordination involves orchestrating the patient's journey from evaluation to recovery, including vigilant monitoring for potential complications. Collaborative teamwork ensures prompt response to adverse events and overall enhances patient safety. This collective effort aims to improve patient-centered care, minimize risks, and elevate team performance throughout the CPB procedure.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

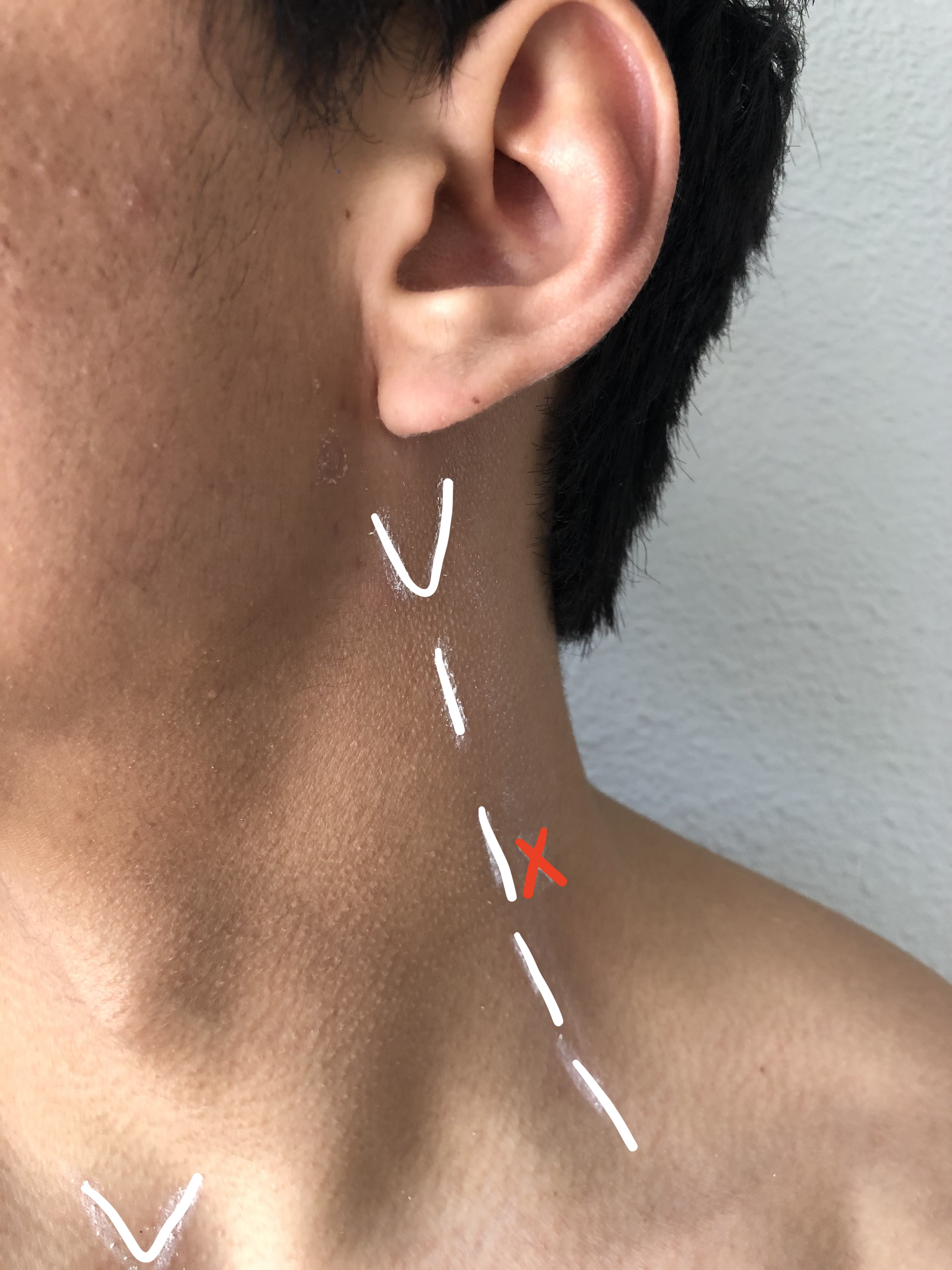

Cervical Plexus Block Probe Placement. Correct probe placement is at the middle of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle for a superficial cervical plexus block. Inserting the needle at the point marked by the red X positions it correctly in the initial step of the procedure.

Contributed by J Hipskind, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Mastoid Process. The white "V" inferior to earlobe is over the mastoid process. The dotted line is the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The red "X" is the mid-point where the block needle is inserted. The midline "V" is over the sternal notch. This approximates the inferior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Contributed by J Hipskind, MD

References

Herring AA, Stone MB, Frenkel O, Chipman A, Nagdev AD. The ultrasound-guided superficial cervical plexus block for anesthesia and analgesia in emergency care settings. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2012 Sep:30(7):1263-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.06.023. Epub 2011 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 22030184]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFlaherty J, Horn JL, Derby R. Regional anesthesia for vascular surgery. Anesthesiology clinics. 2014 Sep:32(3):639-59. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2014.05.002. Epub 2014 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 25113725]

Calderon AL, Zetlaoui P, Benatir F, Davidson J, Desebbe O, Rahali N, Truc C, Feugier P, Lermusiaux P, Allaouchiche B, Boselli E. Ultrasound-guided intermediate cervical plexus block for carotid endarterectomy using a new anterior approach: a two-centre prospective observational study. Anaesthesia. 2015 Apr:70(4):445-51. doi: 10.1111/anae.12960. Epub 2014 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 25440694]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePerisanidis C, Saranteas T, Kostopanagiotou G. Ultrasound-guided combined intermediate and deep cervical plexus nerve block for regional anaesthesia in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Dento maxillo facial radiology. 2013:42(2):29945724. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/29945724. Epub 2012 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 22933534]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHo B, De Paoli M. Use of Ultrasound-Guided Superficial Cervical Plexus Block for Pain Management in the Emergency Department. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Jul:55(1):87-95. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.04.030. Epub 2018 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 29858144]

Ciftci T, Daskaya H, Yıldırım MB, Söylemez H. A minimally painful, comfortable, and safe technique for hemodialysis catheter placement in children: superficial cervical plexus block. Hemodialysis international. International Symposium on Home Hemodialysis. 2014 Jul:18(3):700-4. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12164. Epub 2014 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 24708342]

Adamczyk K, Koszela K, Zaczyński A, Niedźwiecki M, Brzozowska-Mańkowska S, Gasik R. Ultrasound-Guided Blocks for Spine Surgery: Part 1-Cervix. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2023 Jan 23:20(3):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20032098. Epub 2023 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 36767465]

Goyal S, Kumar A, Mishra P, Goyal D. Efficacy of interventional treatment strategies for managing patients with cervicogenic headache: a systematic review. Korean journal of anesthesiology. 2022 Feb:75(1):12-24. doi: 10.4097/kja.21328. Epub 2021 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 34592806]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKim HY, Soh EY, Lee J, Kwon SH, Hur M, Min SK, Kim JS. Incidence of hemi-diaphragmatic paresis after ultrasound-guided intermediate cervical plexus block: a prospective observational study. Journal of anesthesia. 2020 Aug:34(4):483-490. doi: 10.1007/s00540-020-02770-2. Epub 2020 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 32236682]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGitman M, Fettiplace MR, Weinberg GL, Neal JM, Barrington MJ. Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity: A Narrative Literature Review and Clinical Update on Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2019 Sep:144(3):783-795. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005989. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31461049]

Jarvis MS, Sundara Rajan R, Roberts AM. The cervical plexus. BJA education. 2023 Feb:23(2):46-51. doi: 10.1016/j.bjae.2022.11.008. Epub 2022 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 36686890]

Saranteas T, Kostroglou A, Efstathiou G, Giannoulis D, Moschovaki N, Mavrogenis AF, Perisanidis C. Peripheral nerve blocks in the cervical region: from anatomy to ultrasound-guided techniques. Dento maxillo facial radiology. 2020 Dec 1:49(8):20190400. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20190400. Epub 2020 Mar 16 [PubMed PMID: 32176537]

Tran DQ, Dugani S, Finlayson RJ. A randomized comparison between ultrasound-guided and landmark-based superficial cervical plexus block. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2010 Nov-Dec:35(6):539-43. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181faa11c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20975470]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence