Introduction

Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis, also known as chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis (CNH), is a relatively common benign inflammatory condition that affects the skin and cartilage of the pinna. The condition, also known as Winkler disease, was named for the Swiss dermatologist who first described it in Lucerne in 1916.[1] It was further characterized in 1918 by Foerster, who also outlined the disease's microscopic, clinical, and treatment details.[2][3]

This condition commonly affects the helix of the pinna, although in certain cases, the antihelix may be affected. For this reason, some have suggested renaming the condition chondrodermatitis nodularis auricularis. Other synonyms for the condition are nodular chondrodermatitis and chondrodermatitis nodularis antihelicis.[4][5]

The appearance of the lesion and the pain associated with it often lead clinicians to biopsy it out of concern for malignancy, such as squamous cell carcinoma, but CNH is histologically very distinct from cutaneous carcinomas despite its gross features and presentation.

It is believed to result from pressure on the auricle but can be exacerbated by various factors. The predominant presenting symptom is ear pain, usually at the helix. Pressure offloading remedies constitute the first line of therapy. Surgery to remove the lesion should be the last resort. Improving healthcare professionals' understanding of how to promptly evaluate and treat this condition will lead to better patient outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The exact etiology behind the development of CNH remains unclear. Most authors believe it is caused by chronic and excessive pressure on the pinna. Consistently sleeping on the same side seems to contribute to the condition. Other causes of pressure include the continuous and prolonged use of hearing aids, headphones, and other headgear.

CNH may also be associated with autoimmune and connective tissue disorders, especially in young female patients. Anatomical features like a protruding helix or antihelix have also been considered potential contributing factors. Additional predisposing conditions include repeated trauma, surgery, radiation, solar damage, and exposure to cold weather.[6][7][8]

Certain unique anatomical features make the pinna vulnerable to the development of CNH, specifically minimal subcutaneous tissue and a limited blood supply. The auricular cartilage is at risk for damage due to pressure and cold as a result of the thinness of its skin and subcutaneous tissue. The nature of the auricle as an appendage on the side of the head also limits its vascularity, which further compounds the problem by delaying the healing process and increasing the chances of ischemia.[9]

Epidemiology

CNH probably occurs commonly but is infrequently described or studied in the literature. For this reason, the exact incidence remains unknown. When not associated with autoimmune processes, the condition much more commonly affects men, usually of middle age or older (70% to 90% of patients). Still, it may affect women and younger adults, although only very rarely children.[1] CNH can occur in all ethnicities; however, it is more frequent among fair-skinned people with a history of chronic sun exposure.[7]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathological mechanism behind CNH remains unknown; however, several risk factors have been identified, as mentioned above. The perichondrial vasculitis theory, described in 2009 by Upile et al, proposes that the disease process begins as a result of pressure on the auricle, potentially exacerbated by consistently sleeping on the same side of the body and prominauris, which subsequently causes arteriolar narrowing in the perichondrium of the helix. This leads to ischemia, necrosis, and exposure of underlying cartilage. Ultimately, a foreign body reaction ensues, resulting in severe localized inflammation and the development of CNH.[10][11][12]

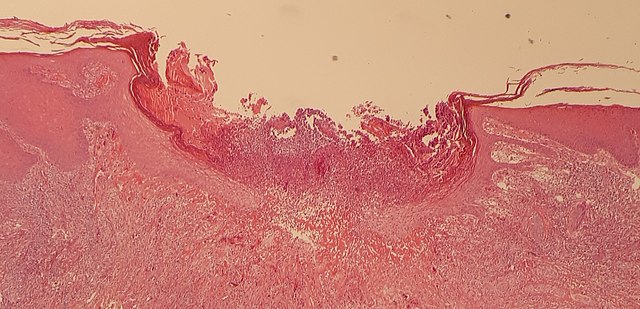

Histopathology

Histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis with adjacent hyperplasia of the epithelium, and substantial destruction of dermal tissue, usually lined by sclerotic tissue (see Image. Histopathology of Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis). Other features include the proliferation of dermal vessels and perichondritis with or without the destruction of underlying cartilage.[13][12][14] In cases where pain is a prominent feature, neural hyperplasia may be associated with the lesion.[15]

History and Physical

History

CNH patients typically present with the complaint of a painful nodule on the helix or antihelix of the pinna without a known history of trauma. CNH primarily occurs on the dependent ear of patients who sleep in a lateral decubitus position, more often the right ear in men and the left ear in women.[16] The condition classically presents unilaterally; nevertheless, bilateral ear involvement is also observed. Prominauris, wearing headgear or hearing aids, frequent talking on the telephone, and an autoimmune predisposition often precipitate onset. The nodule grows rapidly and then typically plateaus in size. Nocturnal pain is the most frequent symptom. Only a few cases have been reported with daytime pain, usually worsened by touching the ear.

Physical Examination

Physical examination usually reveals a well-circumscribed, rounded nodule with raised edges and a crust in its center, often overlying an ulcer that may have exposed cartilage at the bottom (see Image. Skin Changes Typical for Chondrodermatitis Helicis Nodularis Over the Pinna of the Left Ear). Occasionally, the lesion may be flat or tethered to surrounding skin via scarring.[1] The nodule typically has a diameter of 4 mm to 6 mm and may be surrounded by an erythematous area, particularly when painful. The most common site is the apex of the helix. The lesion tends to be firm, tender, and usually fixed to the underlying auricular cartilage. Other associated features include bleeding and exudate accumulation after removal of the crust. The development of CNH on the antihelix is more common among females than males. Rarely, appearance at other sites, such as the external auditory canal and posterior part of the pinna, has been reported.[17]

Evaluation

Diagnosis of CNH begins with a clinical examination. Histopathological examination of a skin biopsy may confirm the diagnosis. Some authors recommend laboratory studies to rule out systemic illnesses such as dermatomyositis, scleroderma, thyroid disorders, and other collagen vascular diseases, especially in adults younger than 40 years of age.[6][3][7]

Treatment / Management

There are several therapeutic options for the management of CNH. These can be broadly divided into conservative treatment and surgical excision.[12][13][7]

Conservative Treatment

- Pressure-relieving prosthesis/padding is a cost-effective and inexpensive treatment method. The primary goal of these prostheses is to relieve or eliminate pressure on the lesion. They are available in various forms, such as self-adherent foam sponges, foam bandages attached to the head, and doughnut pillows for sleeping. These methods are met with variable success, predominantly dependent upon patient compliance rates, but successful treatment rates may be as high as 87%.[18]

- Some clinicians have used topical and intralesional steroids; however, in the absence of interventions to alleviate physical pressure, steroids do not appear to be effective.

- Hyaluronic acid injection may provide relief by offering cushioning and insulation (as a supplement to the thin subcutaneous tissue that naturally exists in the area in question).[19]

- Photodynamic therapy may be effective; however, a disadvantage of this modality is the requirement for multiple treatment sessions.

- Carbon dioxide/argon LASER is another treatment option. The lesion is ablated with the laser, and the wound is allowed to heal by secondary intention. This essentially represents an alternative to conventional surgical excision.

- Topical application of 2% nitroglycerine paste twice daily has been shown to relieve symptoms and appearance by improving perfusion to the affected area. Nitroglycerine patches may be used as a substitute.

- Diltiazem topical cream has also been described as an effective alternative.

- Cryoablation with liquid nitrogen is another option to remove the lesion.

- Electrocauterization/curettage is yet another treatment modality, basically an alternative to surgical excision with a blade. (B2)

Surgery

Many techniques have been developed over the years for surgical excision of CNH. These include wedge excision with margins followed by auricular reconstruction with primary closure or local flaps, removal of the lesion skin and cartilage, and skin-sparing, cartilage-only excision techniques. Most studies agree that the simplest approach, with primary excision and meticulous trimming of cartilage, is the method of choice and provides adequate results. Nevertheless, recurrence rates may be as high as 30%.[18] A less invasive "punch and graft" technique has also been described, in which the lesion is removed with a biopsy punch, and a small, full-thickness skin graft is applied to the wound. The recurrence rate for this technique is reported to be 17%.[20](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

CNH may be confused with a malignant skin condition such as basal cell carcinoma due to its nodular appearance and central crusting. Larger, inflamed lesions may mimic squamous cell carcinoma. Gouty tophi are also in the differential diagnosis; however, unlike CNH, tophi appear as multiple lesions and tend to occur at other sites, such as fingers and toes. Keratoacanthoma may appear similar to CNH initially but grows much faster and classically resolves spontaneously after a few months due to its growth outstripping its blood supply. CNH is unlikely to resolve spontaneously.[21] CNH lesions with substantial keratosis may resemble seborrheic or keratotic dermatitis and verruca vulgaris.[1]

Prognosis

CNH has a good prognosis, although recovery with conservative measures typically takes months. Spontaneous resolution is extremely rare. Recurrence is often seen when lifestyle modifications are not maintained.

Complications

While CNH is unlikely to resolve spontaneously, its progression tends to be limited to a single, well-circumscribed lesion measuring 4 mm to 6 mm in diameter. Leaving the lesion untreated does not put the patient at risk for additional long-term sequelae; however, the patient may lose sleep and suffer chronic discomfort because the lesions are uncomfortable. Additionally, the lesions may become infected due to violation of the skin and potential exposure of the underlying cartilage. Complications may also arise from the treatment, particularly surgical procedures, which may heal poorly or fail to alleviate the problem. If a surgical resection leaves a palpable cartilaginous edge or point, chronic pressure may lead to the development of a de novo lesion.

Deterrence and Patient Education

While it is certainly unnecessary to counsel all patients on the importance of shifting from side to side at night to prevent the development of CNH, it is important for primary care providers to be aware of the condition and to have a low threshold for advising patients to avoid pressure on their ears should painful lesions with a central crust appear along the helix or antihelix, because a significant proportion of CNH cases can be remedied with conservative measures over several months. Taking a break from headgear or hearing aids, finding a different way to talk on the telephone, protecting the ears from the cold, and sleeping on a different side or on a doughnut-shaped pillow can all play important roles in the resolution of CNH. It is essential to have a low threshold for biopsy of these lesions, particularly if they are not painful because they tend to appear in areas that are prone to developing non-melanomatous skin cancer, especially in males older than 40 years with a history of skin damage due to sun exposure.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CNH is best managed by an interprofessional team, including otolaryngology or dermatology nurses. Health professionals caring for patients with CNH should possess skills in accurate diagnosis, distinguishing CNH from potential malignancies, and employing appropriate evaluation techniques. This includes proficiency in dermatological examinations. Developing a strategic approach involves formulating evidence-based treatment plans for CNH, considering individual patient factors and preferences. Implementing preventive strategies, such as educating patients about risk factors like pressure points and lifestyle modifications, contributes to a proactive care strategy. Health professionals should strategize for long-term management, minimizing recurrences, and optimizing patient outcomes.

Over the years, many treatments have been proposed for this condition, including prosthetic appliances and surgical excision. To improve outcomes, clinicians should first attempt pressure-reducing remedies. Surgery has historically been the gold standard therapy, but recent advances in conservative therapies have challenged this treatment paradigm. Due to a lack of large studies, there is no general consensus on which management strategies are most effective. For this reason, patients should be counseled initially to avoid pressure on the ear, which appears to provide symptom relief in most cases.[13]

Timely and collaborative exchanges of information between physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other team members facilitate a cohesive approach to CNH management. Coordinating efforts to address the underlying causes of CNH, such as lifestyle factors and pressure points, enhances the effectiveness of interventions. Seamless coordination ensures that patients receive comprehensive care, minimizing the impact of CNH on their overall well-being.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Wagner G, Liefeith J, Sachse MM. Clinical appearance, differential diagnoses and therapeutical options of chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis Winkler. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2011 Apr:9(4):287-91. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07601.x. Epub 2011 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 21276202]

Cohen PR, Erickson CP, Calame A. Painful tumors of the skin: "CALM HOG FLED PEN AND GETS BACK". Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2019:12():123-132. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S193359. Epub 2019 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 30858718]

Morgado-Carrasco D, Fustà-Novell X, Podlipnik S, Ferrandiz L. Dermoscopic Features of Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis: A Case Series. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2019 Jan:9(1):52-53. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0901a12. Epub 2019 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 30775149]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDarragh CT, Om A, Zwerner JP. Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis of the Right Nasal Vestibule. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2018 Nov:44(11):1475-1476. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001515. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30359339]

Di Berardino F, Zanetti D. The Direct Use of Mobile Phone and the Occurrence of Chondrodermatitis Nodularis in the Antihelix: An Exemplificative Case. Indian dermatology online journal. 2018 Nov-Dec:9(6):438-440. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_57_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30505787]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGarcía-García B, Munguía-Calzada P, Aubán-Pariente J, Junceda-Antuña S, Zaballos P, Argenziano G, Vázquez-López F. Dermoscopy of chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. Archives of dermatological research. 2018 Sep:310(7):551-560. doi: 10.1007/s00403-018-1844-6. Epub 2018 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 29926164]

Salah H, Urso B, Khachemoune A. Review of the Etiopathogenesis and Management Options of Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis. Cureus. 2018 Mar 26:10(3):e2367. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2367. Epub 2018 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 29805936]

Armenta AM, Codrea VA, Sou EL, Wagner RF Jr. Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Helicis After Mohs Micrographic Surgery and Radiation Therapy. Cutis. 2023 May:111(5):E5-E7. doi: 10.12788/cutis.0773. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37406315]

Elsensohn A, Getty S, Shiu J, de Feraudy S. Intradermal Proliferative Fasciitis Occurring With Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Helicis. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2018 Feb:40(2):139-141. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29210713]

Upile T, Patel NN, Jerjes W, Singh NU, Sandison A, Michaels L. Advances in the understanding of chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helices: the perichondrial vasculitis theory. Clinical otolaryngology : official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2009 Apr:34(2):147-50. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2008.01851.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19413613]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKumar P, Barkat R. Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis. Indian dermatology online journal. 2017 Jan-Feb:8(1):48-49. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.198767. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28217474]

Shah S, Fiala KH. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis: A review of current therapies. Dermatologic therapy. 2017 Jan:30(1):. doi: 10.1111/dth.12434. Epub 2016 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 27723195]

Juul Nielsen L, Holkmann Olsen C, Lock-Andersen J. Therapeutic Options of Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Helicis. Plastic surgery international. 2016:2016():4340168. doi: 10.1155/2016/4340168. Epub 2016 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 26925262]

Rickli H, Hardmeier T. [Winkler's chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis]. Der Pathologe. 1988 Jan:9(1):25-9 [PubMed PMID: 3279412]

Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Peltre B. Neural hyperplasia in chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2006 Nov:55(5):844-8 [PubMed PMID: 17052491]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFeldman AL, Manstein CH, Manstein ME, Czulewicz A. Chondrodermatitis nodularis auricularis: a new name for an old disease. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2009 Jan:123(1):25e-26e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318194d1d4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19116517]

Cox NH. Posterior auricular chondrodermatitis nodularis. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2002 Jun:27(4):324-7 [PubMed PMID: 12139683]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoncrieff M, Sassoon EM. Effective treatment of chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis using a conservative approach. The British journal of dermatology. 2004 May:150(5):892-4 [PubMed PMID: 15149500]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCarey W. Intralesional Hyaluronic Acid Injection for Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Helicis: A Novel Treatment for Rapid Relief of Pain and Healing of Ulcerations. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2021 Mar 1:47(3):373-376. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002790. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34328289]

Rajan N, Langtry JA. The punch and graft technique: a novel method of surgical treatment for chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. The British journal of dermatology. 2007 Oct:157(4):744-7 [PubMed PMID: 17672876]

Zito PM, Scharf R. Keratoacanthoma. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763106]