Introduction

Laryngeal mask airways (LMA) are single-use or reusable supraglottic airway devices that may be used as a temporary method to maintain an open airway during the administration of anesthesia or as an immediate life-saving measure in a difficult or failed airway as outlined in the difficult airway algorithm published by many societies of anesthesiology worldwide. Introduced into clinical practice in the 1980s, they were initially used predominantly in the operating room but have become widely used in the intensive care unit, emergency department, and field settings. LMAs are easier to use and more effective than a bag-valve-mask in the hands of basic life support providers and may be used as an alternative to intubation by advanced life support providers. Some models may be used as a conduit to facilitate endotracheal intubation.[1][2][3]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Supraglottic devices, like the LMA, are designed to be inserted blindly through the mouth and into the hypopharynx to seal around the glottic opening allowing for ventilation. The mnemonic RODS can be used to predict difficulty in either placing an extraglottic device or in providing adequate gas exchange through one. RODS stands for Restriction, Obstruction/Obesity, Disrupted or Distorted anatomy, and Short thyromental distance. Restriction refers to both increased airway resistance - extraglottic devices have lower leak pressures than endotracheal tubes - as well as restricted mouth opening insufficient to allow for the passage of the device. Patients with upper or lower airway obstruction due to a tumor or foreign body may make passage of or ventilation through the device difficult or impossible. Obese patients may have redundant tissue, making it more difficult to seat the device in place, and the increased ventilatory pressures required in obese patients may increase the likelihood of a leak. Distortion or disruption of the airway from the midline makes the device less likely to seat properly. Small mandibular spaces, assessed by shortened thyromental distance, are associated with the difficult use of extraglottic devices due to the position of the tongue.

Indications

LMAs may be used as a primary airway management devices in the operative setting in pre-selected, fasted patients. In the emergency setting, LMAs are used as a temporary bridge to intubation by pre-hospital providers, in cardiac arrest situations, as a rescue device in “can’t intubate, can’t oxygenate” situations, as a means to attempt ventilation in a failed airway situation followed by either intubation through the device or while a surgical airway is performed.[4][5][6]

LMAs are excellent alternatives to the use of bag masks to reduce the risk of gastric inflation, thus decreasing the risk of aspiration. While it may decrease the risk of aspiration, it is far less protective than an endotracheal tube. LMAs are an effective method of ventilation and should be utilized unless it is ineffective in patients requiring prolonged mask ventilation.

LMAs have been used successfully with pediatric patients, adults, and individuals with obesity.

Contraindications

The LMA offers a great alternative to endotracheal intubation in pre-fasted, selected patients and may be associated with fewer complications as compared to intubation in selected patients. Despite this, significant complications may result from the utilization of an LMA, including laryngospasm, nausea, vomiting, aspiration, and coughing. They may stimulate the gag reflex and, therefore, should not be used in a conscious or awake patient. Contraindications to elective use include poor pulmonary compliance, high airway resistance, pharyngeal pathology, risk for aspiration, and/or airway obstruction below the larynx.

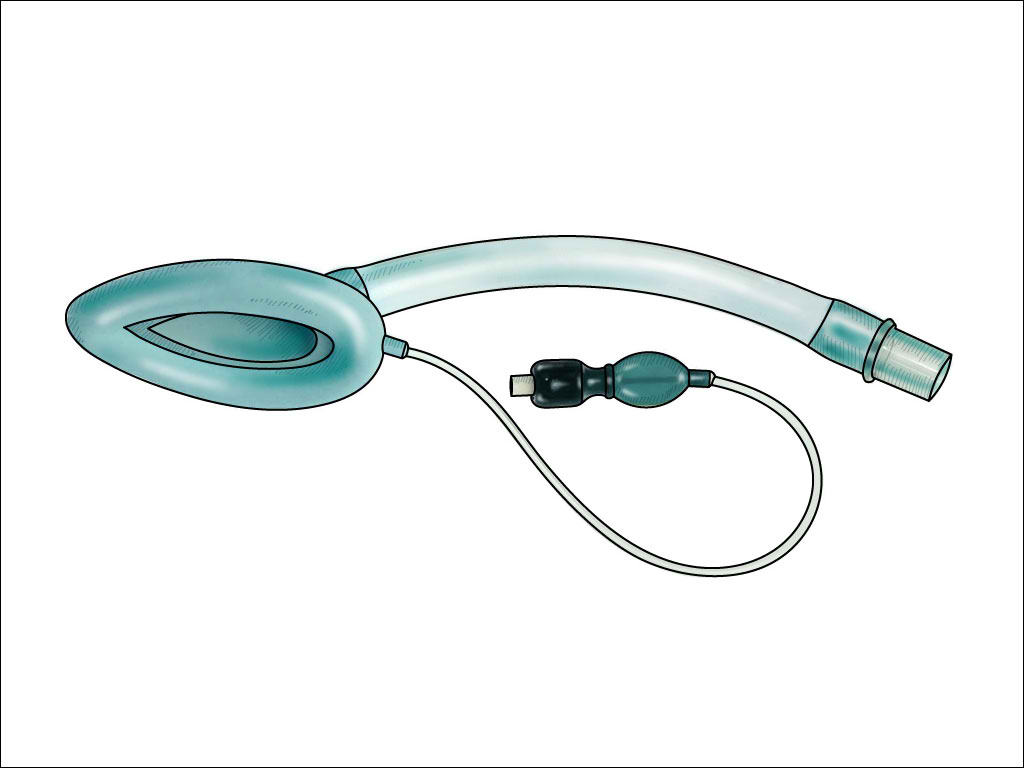

Equipment

LMAs come in many forms and configurations. They consist of a tube attached to an inflatable, elliptical cuff designed to cover the supraglottic area, facilitating an open airway passage and allowing for either spontaneous or positive pressure ventilation. While the original LMA was a multi-use device, cleaning requirements, and high cost have steered providers towards less costly, single-use LMAs. Several configurations are available from multiple vendors. The original LMA design has crossbars over the aperture designed to prevent passive herniation of the epiglottis into the opening. However, that design makes intubation through that device much more challenging. Those first-generation devices are still commonly used for routine cases due to their low cost and they have low complication rates. Newer second-generation LMAs are now available and provide for higher seal pressures due to improved seal material or design, have no aperture bars, allow for easier intubation using regular endotracheal tubes, and provide a gastric access port to vent or aspirate gastric contents. Some even incorporate a bite block.

The LMA Fastrach, also called the ILMA, is specifically designed to facilitate blind intubation. It is available in both reusable and disposable forms and has a handle designed to allow for optimal positioning and a bar designed to elevate the epiglottis out of the way to facilitate intubation. This device is designed for use with specialized endotracheal proprietary tubes made and packaged with the ILMA.

The I-Gel devices are unique in that they have a pre-shaped non-inflatable cuff. They are made from a gel-like substance, which may be easier to insert because there is no cuff to inflate. The i-Gel also allows for the passage of standard endotracheal tubes. It may be used in patients of all ages, from small infants to adults.

Personnel

While initially used by anesthesia providers, success in placing LMAs has been demonstrated by novice intubators, EMS providers, nurses, advanced practice providers, and physicians of multiple specialties.

Preparation

Prior to the insertion of an LMA, the patient should ideally be fasted and assessed for markers of difficulty or contraindications. This may not be possible in emergency situations where it is used as a rescue device. The LMA comes in various sizes, and recommendations are generally weight-based and printed on the package and the devices. For adults, the following is a simple size guide: size three for adults 30 to 50 kg, size four for adults 50 to 70 kg, and size five for adults over 70 kg. In general, the larger size should be chosen for patients between sizes because it will seal more effectively.[7]

Technique or Treatment

Prior to insertion, the device should be placed on a flat surface. The cuff should be inflated and then completely deflated to ensure the cuff is not folded, pressing firmly on the flat surface. Lubricate both sides of the device with a water-soluble lubricant. When there is no risk of neck damage, the neck is extended in a sniffing position. Otherwise, a jaw thrust may be performed to facilitate passage. The LMA is introduced behind the tongue with backward pressure using the index finger, pressing the device against the hard palate until it is completely inserted. Then use the other hand to push the LMA until some resistance is felt and it can go no further. The collar should then be inflated with approximately 20 mL for number three, 30 mL for number four, and 40 mL for number five. This volume may need to be adjusted to optimize the seal and minimize the air leak. Once the cuff is inflated with the designated amount of air and placement is checked by attaching a bag mask and delivering breaths, assessing breath sounds, and/or using continuous waveform capnography or, at a minimum, a CO2 detector device.

Endotracheal intubation can be achieved by inserting the endotracheal tube (ETT) through most second-generation LMAs. Those devices do not have aperture bars at the cuff end and usually have higher seal pressures than the original LMAs that are still frequently used. The LMA Fastrach has a higher rate of intubation success compared to the standard 1 generation and is designed for blind intubation using the company’s proprietary endotracheal tube. However, failure rates can be as high as 40%, and endotracheal intubation is best facilitated under direct visualization using a flexible bronchoscope. Regular endotracheal tubes are usually not long enough to go past the vocal cords when inserted through an LMA. Using either a tube exchanger that slides over a flexible bronchoscope or using a nasal RAE tube, which is longer, will overcome that problem.

Complications

The distal tip of the collar on the LMA may occasionally roll upwards on insertion, which may hinder optimal placement. Some experts recommend partial inflation of the cuff before insertion or inserting the LMA upside-down and rotating it into position to prevent this complication, but there is insufficient evidence to recommend this practice. Forceful insertion may cause abrasion of the pharyngeal tissues or bleeding. Insufflation of the stomach may occur. It is not known to what degree an LMA will prevent aspiration of gastric contents, and it should be considered a temporary or rescue measure in patients at risk for vomiting and aspiration and not considered a replacement for endotracheal intubation. It may be difficult to maintain an effective seal in patients with high airways pressures. The device may become easily malpositioned during CPR or if the patient is moved during transport and must be maintained in the midline.[8]

LMAs are not a good primary airway device in morbidly obese patients as those patients do require higher positive airway pressures that may produce leaks around the LMA cuff. In addition, having morbidly obese patients breathe spontaneously through an LMA during anesthesia may lead to significant hypoventilation due to the position of the patient and the weight of the abdomen.[9]

The complication rates with LMAs are low and less than those associated with both endotracheal intubation and the use of bag valve masks.

Clinical Significance

LMAs have been shown to be as effective as other airway management strategies in patients receiving CPR.

LMAs may be used appropriately and successfully in pediatric patients.

Success rates for blind intubation through an LMA range from 60 to 99%, depending on the device and skill of the operator. Blind intubation rates are highest for the Fastrach LMA (ILMA) as compared to other supraglottic devices but should best be facilitated by flexible fiberoptic guidance whenever possible.

LMAs should not be the final secured airway solution in a failed airway rescue. They can become displaced when changing from a temporarily stable situation to another airway emergency and should be used as a conduit to a secure airway with an endotracheal tube.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

LMAs have an important role in the management of a patient with respiratory distress. While most healthcare workers are familiar with the endotracheal tube, the use of the LMA does require experience. Healthcare workers, including nurse practitioners who have never used an LMA, should first consult with an anesthesiologist before attempting intubation. The LMA is only a temporary solution to the airway and can be easily dislodged with patient movements; hence, it is generally only used in the operating theater.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Strametz R, Bergold MN, Weberschock T. Laryngeal mask airway versus endotracheal tube for percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy in critically ill adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Nov 15:11(11):CD009901. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009901.pub3. Epub 2018 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 30536850]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSingh A, Bhalotra AR, Anand R. A comparative evaluation of ProSeal laryngeal mask airway, I-gel and Supreme laryngeal mask airway in adult patients undergoing elective surgery: A randomised trial. Indian journal of anaesthesia. 2018 Nov:62(11):858-864. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_153_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30532321]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceArmstrong L, Caulkett N, Boysen S, Pearson JM, Knight CG, Windeyer MC. Assessing the Efficacy of Ventilation of Anesthetized Neonatal Calves Using a Laryngeal Mask Airway or Mask Resuscitator. Frontiers in veterinary science. 2018:5():292. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00292. Epub 2018 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 30519563]

Klučka J, Šenkyřík J, Skotáková J, Štoudek R, Ťoukalková M, Křikava I, Mareček L, Pavlík T, Štouračová A, Štourač P. Laryngeal mask airway Unique™ position in paediatric patients undergoing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): prospective observational study. BMC anesthesiology. 2018 Oct 24:18(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0617-2. Epub 2018 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 30355285]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIn CB, Cho SA, Lee SJ, Sung TY, Cho CK. Comparison of the clinical performance of airway management with the i-gel® and laryngeal mask airway SupremeTM in geriatric patients: a prospective and randomized study. Korean journal of anesthesiology. 2019 Feb:72(1):39-46. doi: 10.4097/kja.d.18.00121. Epub 2018 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 30343563]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWhite L, Melhuish T, Holyoak R, Ryan T, Kempton H, Vlok R. Advanced airway management in out of hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Dec:36(12):2298-2306. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.09.045. Epub 2018 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 30293843]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDe Rosa S, Messina A, Sorbello M, Rigobello A, Colombo D, Piccolo A, Bonaldi E, Gennaro P, Urukalo V, Pellizzari A, Bonato R, Carboni SC. Laryngeal Mask Airway Supreme vs. the Spritztube tracheal cannula in anaesthetised adult patients: A randomised controlled trial. European journal of anaesthesiology. 2019 Dec:36(12):955-962. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001106. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31644512]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSabuncu U, Kusderci HS, Oterkus M, Abdullayev R, Demir A, Uludag O, Ozdas S, Goksu M. AuraGain and i-Gel laryngeal masks in general anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Performance characteristics and effects on hemodynamics. Saudi medical journal. 2018 Nov:39(11):1082-1089. doi: 10.15537/smj.2018.11.22346. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30397706]

Kim HY, Baek SH, Cho YH, Kim JY, Choi YM, Choi EJ, Yoon JP, Park JH. Iatrogenic Intramural Dissection of the Esophagus after Insertion of a Laryngeal Mask Airway. Acute and critical care. 2018 Nov:33(4):276-279. doi: 10.4266/acc.2016.00829. Epub 2017 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 31723897]