Introduction

Vertebrae, along with intervertebral discs, compose the vertebral column or spine. The vertebral column extends from the skull to the coccyx and includes the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions. The spine has several significant roles in the body, including protection of the spinal cord and branching spinal nerves, support for the thorax and abdomen, and enabling flexibility and mobility. The intervertebral discs are responsible for this mobility without sacrificing the supportive strength of the vertebral column. The lumbar region contains five vertebrae, denoted L1-L5. The intervertebral discs, along with the laminae, pedicles, and articular processes of adjacent vertebrae, create a space through which spinal nerves exit. The lumbar vertebrae, as a group, produce a lordotic curve.[1]

Typical vertebrae consist of a vertebral body, a vertebral arch, and seven processes. The vertebral body bears the majority of the force placed on the vertebrae. Vertebral bodies increase in size as the column descends. The vertebral body consists of trabecular bone, which contains the red marrow, surrounded by a thin external layer of compact bone. The arch, along with the posterior aspect of the body, forms the vertebral (spinal) canal, which houses the spinal cord. The arch consists of bilateral pedicles, pieces of bone that connect the arch to the body, and bilateral lamina, bone segments that form most of the arch, connecting the transverse and spinous processes. A typical vertebra also contains four articular processes, two superior and two inferior, which contact the inferior and superior articular processes of the two adjacent vertebrae, one superior and one inferior.

The point at which superior and articular facets meet is known as a facet, or zygapophyseal, joint. These maintain vertebral alignment, control the range of motion, and are weight-bearing in certain positions. The spinous process projects posteriorly and inferiorly from the vertebral arch and overlaps the inferior vertebrae to various degrees, depending on the region of the spine. Lastly, the two transverse processes project laterally from the vertebral arch in a symmetric fashion.[2]

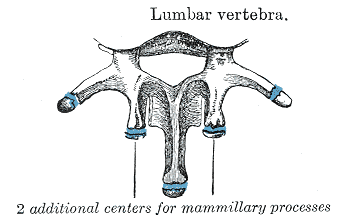

Typical lumbar vertebrae have several features distinct from those typical of cervical or thoracic vertebrae. The most notable distinction is the presence of a large vertebral body. The spinous process is short and thick, relative to the size of the vertebra, and projects perpendicularly from the body. The articular facets are markedly vertical, with the superior facets directed posteromedially and medially. The facets also have the unique feature of a curved articular surface. This is one feature that differentiates lumbar vertebrae from thoracic. There is also the mammillary process on the posterior aspect of the superior articular process. Disc thickness generally increases from rostral to caudal, with the lumbar intervertebral disc height greater than cervical and thoracic intervertebral discs.[3][4]

There is only one lumbar vertebra that may be considered atypical. L5 has the largest body and transverse processes of all vertebrae. The anterior aspect of the body has a greater height compared to the posterior. This creates the lumbosacral angle between the lumbar region of the vertebrae and the sacrum.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

As with all physiology, the anatomy of a structure is related directly to its function. The lumbar vertebrae have the largest bodies of the entire spine and progressively increase in size, moving more inferiorly. This marked increase in size reflects the responsibility of the lumbar spine to support the weight of the entire upper body.

Due to the size of the intervertebral discs relative to the size of the vertebral body and the size and horizontal direction of the spinous processes, the lumbar spine has the greatest degree of extension of the vertebral column. The near-vertical orientation of the superior articular facets allows for flexion, extension, and lateral flexion but limits rotation. The mammillary processes provide a point of attachment for the intertransversarii muscles and multifidus. The curvature of articular facets is thought to assist in the stabilization and weight-bearing capacity of the lumbar vertebrae.[5]

Embryology

All vertebrae begin ossification in the embryonic period of development around 8 weeks of gestation. The vertebrae ossify from three primary ossification centers: one in the endochondral centrum (which will develop into the vertebral body) and one in each neural process (which will develop into the pedicles). This begins at the thoracolumbar junction and proceeds in the cranial and caudal directions. The neural processes fuse with the centrum between three and six years of age.[6]

During puberty, five secondary ossification centers develop at the tip of the spinous proc, both transverse processes and on the superior and inferior surfaces of the vertebral body. The ossification centers on the vertebral body are responsible for the superior-inferior growth of the vertebrae. Ossification is complete around the age of 25.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The lumbar vertebrae are supplied mainly by the subcostal and lumbar arteries. These main arteries branch out into the periosteal and equatorial arteries, which in turn branch into anterior and posterior canal branches. Anterior vertebral canal branches send nutrient arteries into the vertebral body to supply the red marrow.[7]

Spinal veins form venous plexuses inside and outside the vertebral canal. These plexuses lack valves and allow blood flow to occur superiorly or inferiorly, depending on pressure gradients. The blood eventually drains into the segmental veins of the trunk.

Nerves

Meningeal branches of spinal nerves innervate all vertebrae. These are responsible for the paralumbar spasm and pain observed in cases of herniated nucleus pulposus of the lumbar spine.

Muscles

Lumbar vertebrae provide attachment points for numerous muscles: erector spinae, interspinales, intertransversarii, latissimus dorsi, rotatores, and serratus posterior inferior.

Surgical Considerations

Several surgical procedures can be performed on the lumbar spine, especially for degenerative, infective, and traumatic spinal conditions. These operative procedures include the following:

Clinical Significance

The vertebral venous plexuses lack valves. Therefore, they allow for cancer metastasis from the pelvis through the vertebral venous plexus. An example of this phenomenon involves the metastatic spread of prostate cancer to the vertebral column. Tumors in bone are extremely painful.

The lumbar region has a lower incidence of neurological injury due to fractures compared to those in the thoracic region. This is due to the large size of the vertebral canal, the inferior end of the spinal cord at the level of L2, as well as the relative resilience of the nerve roots of the cauda equina (Latin = horse's tail). This is why spinal taps are performed inferior to L2; the roots forming the cauda equina, suspended in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), move out of the way of the spinal needle.[14][15]

Spinal nerves increase in size as the spinal cord descends; however, the intervertebral foramina decrease in size. In addition to pathology such as intervertebral disc degeneration that brings two adjacent vertebrae closer together, this combination commonly leads to lateral canal stenosis, a condition in which the vertebral foramen compresses the spinal nerves. This may be treated with a laminectomy, in which the spinous process, laminae, and pedicles are removed to create more room for the spinal cord and spinal nerves.

Disc herniations can be corrected using various surgical procedures (laminectomy, microdiscectomy, to remove the herniated nuclear tissue and alleviate nerve root pressure. In some instances, non-invasive techniques may work in these cases, although the data at present remains equivocal.[16]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

DeSai C, Reddy V, Agarwal A. Anatomy, Back, Vertebral Column. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30247844]

Lafian AM, Torralba KD. Lumbar Spinal Stenosis in Older Adults. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 2018 Aug:44(3):501-512. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2018.03.008. Epub 2018 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 30001789]

Berven S, Wadhwa R. Sagittal Alignment of the Lumbar Spine. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2018 Jul:29(3):331-339. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2018.03.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29933801]

Waxenbaum JA, Reddy V, Futterman B. Anatomy, Back, Intervertebral Discs. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262063]

Berger-Pasternak B, Brylka D, Sipko T. Lumbar Spine Kinematics in Asymptomatic People When Changing Body Position From Sitting to Standing. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2021 Feb:44(2):113-119. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2020.07.014. Epub 2021 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 33431283]

Kalamchi L, Valle C. Embryology, Vertebral Column Development. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751107]

Can H, Diren F, Peker B, Gomleksiz C, Guclu DG, Kucuk C, Civelek E, Aydoseli A, Sencer A. Morphometric Analysis of Lumbar Arteries and Relationship with Intervertebral Discs: A study of Surgical Anatomy on Human Fresh Cadavers. Turkish neurosurgery. 2020:30(4):577-582. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.29021-20.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32530478]

Fan Y, Zhou S, Xie T, Yu Z, Han X, Zhu L. Topping-off surgery vs posterior lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar disease: a finite element analysis. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2019 Dec 30:14(1):476. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1503-4. Epub 2019 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 31888664]

Jin M, Zhang J, Shao H, Liu J, Huang Y. Percutaneous Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Interbody Fusion for Degenerative Lumbar Diseases: A Consecutive Case Series with Mean 2-Year Follow-Up. Pain physician. 2020 Mar:23(2):165-174 [PubMed PMID: 32214300]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEpstein NE. Review of Risks and Complications of Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF). Surgical neurology international. 2019:10():237. doi: 10.25259/SNI_559_2019. Epub 2019 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 31893138]

Tang L, Wu Y, Jing D, Xu Y, Wang C, Pan J. A Bayesian network meta-analysis of 5 different fusion surgical procedures for the treatment of lumbar spondylolisthesis. Medicine. 2020 Apr:99(14):e19639. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019639. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32243393]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLi R, Li X, Zhou H, Jiang W. Development and Application of Oblique Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Orthopaedic surgery. 2020 Apr:12(2):355-365. doi: 10.1111/os.12625. Epub 2020 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 32174024]

Roumeliotis AG, Swiatek PR, Goedderz C, Mathur P, Zhang Y, Gerlach EB, Divi SN, Hsu WK, Patel AA. Patient and Surgeon Perceptions Regarding Microdiscectomy Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Social Media Posts. International journal of spine surgery. 2023 Jun:17(3):434-441. doi: 10.14444/8450. Epub 2023 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 37085321]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatel EA, Perloff MD. Radicular Pain Syndromes: Cervical, Lumbar, and Spinal Stenosis. Seminars in neurology. 2018 Dec:38(6):634-639. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673680. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30522138]

Shin EH, Cho KJ, Kim YT, Park MH. Risk factors for recurrent lumbar disc herniation after discectomy. International orthopaedics. 2019 Apr:43(4):963-967. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4201-7. Epub 2018 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 30327934]

Hornung AL, Baker JD, Mallow GM, Sayari AJ, Albert HB, Tkachev A, An HS, Samartzis D. Resorption of Lumbar Disk Herniation: Mechanisms, Clinical Predictors, and Future Directions. JBJS reviews. 2023 Jan 1:11(1):. doi: e22.00148. Epub 2023 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 36722839]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence