Introduction

The great vessels are a part of the vascular system that first appears in the mid-third week of development from mesoderm/ectoderm-derived angiogenic cells. The arteries arise from the combination of the ectoderm (cells from the neural crests) and the mesoderm (pharyngeal mesoderm).

The first arteries that develop are the right and left primitive aortae, which are a continuation of endocardial cardiac tubes. These primitive aortae curve posteriorly in the first pharyngeal arch, around the anterior part of foregut and then continue posteriorly as two dorsal aortae. These two aortae also fuse cranially close to the heart, forming the aortic sac. The aortic sac continues caudally as truncus arteriosus and lies ventral to the pharynx. The two dorsal aortae lie dorsal to the primitive gut and pass caudally and fuse at the distal end to form a common aorta while the cranial part remains separate.

Development

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Development

The aortic sac and the two dorsal aortae connect ventrally with aortic arches that are six pairs of arteries. The aortic arches run in the pharyngeal arches along the pharyngeal wall. During the development of the pharyngeal arches, the aortic sac sends a pair of branches to each pharyngeal arch which curves around the pharynx in the corresponding pharyngeal arch and eventually ends in the dorsal aorta. This artery is called an aortic arch artery, and these six pairs of arteries are never present at the same time in an embryo; by the time the third pair develops, the first pair has regressed.[1]

The aortic arches decrease in number and undergo rearrangement, and each arch then gives rise to a structure vital for adult life. The structures arising from the aortic arches are as follows[2]:

First aortic arch: It regresses except for a very small part that gives rise to the maxillary artery.

Second aortic arch: It regresses except for a very small part giving rise to the stapedial artery.

Third aortic arch: This arch is the source of the common carotid artery and the proximal part of the internal carotid artery, and the external carotid which arises as a bud from this arch.

Right Fourth aortic arch: Is the genesis of the proximal part of the right subclavian artery.

Left Fourth aortic arch: Gives rise to the medial portion of the arch of the aorta.

Fifth aortic arch: The fifth aortic arch regresses completely and very early in the development.

Sixth aortic arch: Either of the sixth aortic arches divides into ventral and dorsal segments, and therefore, their derivatives also divide into these two segments.

- Right Sixth Arch:

- Ventral: Gives rise to the right pulmonary artery.

- Dorsal: It degenerates completely and loses its connection with the dorsal aorta.

- Left Sixth Arch

- Ventral: It gives rise to the left pulmonary artery that goes to the left pulmonary bud.

- Dorsal: It forms a vital connection during intrauterine life between the left pulmonary artery and the arch of the aorta. This structure is called ductus arteriosus.

The aortic sac has two horns; right and left.[3]

- The right horn gives rise to the brachiocephalic artery, which is continuous with the right subclavian artery stem and the right common carotid artery.

- The left horn and the stem of the aortic sac give rise to the proximal part of the arch of the aorta.

Development of the Aortic Arch:

The arch of the aorta has origins from multiple structures. The part of the aortic arch proximal to the origin of the innominate artery is the proximal part of the aorta, and it arises from the stem of the aortic sac. The area between the innominate artery and the left common carotid is called the middle region of the aortic arch and develops from the left horn of the aortic sac. The part of the aortic arch distal to the left common carotid artery forms from the left fourth aortic arch and the lower part of the left dorsal aorta.[4]

Both the dorsal aortae also give rise to seven cervical intersegmental arteries, and upper six of those anastomose vertically which eventually gives rise to the second part of the vertebral artery, superior intercostal artery, and the deep cervical artery. The last seventh segmental artery gives rise to the subclavian artery.[5]

The Common Dorsal Aorta:

It forms when the right and left dorsal aorta merge at the level of fourth thoracic to fourth lumbar somite segment. It gives off several branches which later become blood supply to vital organs in the adult life[6]:

- Splanchnic arteries:

- Ventral splanchnic arteries[7]:

- Arise from the ventral aspect.

- Supply the blood for the foregut, the midgut, and the hindgut.

- Its branches anastomose with each other to form a network that supplies the gut.

- Lateral splanchnic arteries:

- These arteries arise from the lateral aspect of the dorsal aorta in a pair, i.e., right and left.

- Supply structures arising from the intermediate mesoderm

- The middle suprarenal, gonadal, and renal arteries are its branches.

- Ventral splanchnic arteries[7]:

- Intersegmental arteries:

- These arteries arise from the posterolateral aspect of the common dorsal aorta in pairs passing laterally between the somites.

- In adult life, it manifests as the posterior intercostal, lumbar and subcostal arteries.

- The fifth lumbar intersegmental artery gives rise to the external iliac artery

- They anastomose ventrally to form the internal thoracic, inferior, and superior epigastric arteries.

- Umbilical arteries[8]:

- They arise from the dorsal aorta, but once they anastomose and communicate with the intersegmental artery, they disconnect with the dorsal aorta.

- The fifth lumbar intersegmental artery gives rise to the external iliac artery while the umbilical artery is attached to its distal end, which later transforms into the internal iliac artery.

- The proximal part of the parent artery then forms the common iliac artery.

Development of the arteries in the extremities:

- The arteries in the upper extremity develop from the axial artery.

- The axial artery comes from the seventh intersegmental artery and continues distally to form axillary, subclavian, and anterior interosseous arteries.

- The axial artery terminates in the hand and forms the deep palmar arch of the hand in the adult life.

- The anterior interosseous artery gives out a branch called the median artery, which runs alongside the median nerve and merges with the capillary plexus in the hand.

- The axial artery also gives off two more branches in the region of the elbow: the radial and ulnar arteries.

- Similarly, the axial artery in the lower limb is the continuation of the fifth lumbar intersegmental artery and follows the course of and with the sciatic nerve. Therefore, it is named as the sciatic artery as it travels downwards from the gluteal region traversing the back of the thigh, back of the leg and running deep to the popliteus muscle and the calf muscles ending in the sole of the foot after forming a deep vascular plexus.

- The external iliac artery continues in the lower limb to become the femoral artery and travels in the front of the thigh but bends posteriorly to join the axial artery in the popliteal fossa forming the popliteal artery just above the popliteal muscle.

- The tibial arteries originate from the local vascular network in the anterior and posterior portion of the leg and communicate with the popliteal artery.[9]

- In adult life, the axial artery degenerates and leaves behind the inferior gluteal artery, peroneal artery, and the companion artery of the sciatic nerve as remnants.

Cellular

Two types of vascular cells derive from mural cells. The first is the pericyte, which affects more small vessels, while the second type, vascular smooth muscle cells, are found, especially in large vessels. Pericytes play immune functions and can behave like stem cells. Vascular smooth muscle cells are involved in the function of vasoconstriction and vasodilation of the vessels (blood pressure and distribution of blood to the tissues). These cells also have the task of maintaining the morphology of the vessel.

Biochemical

Many molecules stimulate the maturation of mural cells (angiogenic factors and cytokines). For example, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and beta-FGF, transforming growth factor of alpha type (TGF-alpha), angiogenin, interleukin type 8 (IL-8), angiopoietins.

Molecular Level

Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), Notch (receptor affine to integrin proteins) and Gata (transcription factors) families, T-box (a group of transcription factors); myocardin, semaphorin family are protein molecules capable of inducing a correct embryological development of the aortic arch.

Hoxa3 is a protein-coding gene involved in the regulation of the third pharyngeal arch, which molecule comes from the neural crests. This molecule conditions the physiological development of the carotid artery system.

Testing

There was an article on genetic tests published by several groups dealing with cardiac and arterial diseases: European Society of Cardiology Working Group of Grown-Up Congenital Heart Disease, the European Society of Cardiology the European Society of Human Genetics. Genetic testing could help prevent diseases and provide adequate treatment in clinical practice in the near future. Further advances in research are necessary before endorsing genetic testing as a first approach for human embryological assessment.

Pathophysiology

Notch pathway is essential for the construction of the aorta and aortic arch. We know several receptors like Notch1–4, and the related ligands (Jagged1–2, Delta-like1-4); these molecules are found on the surface of the cell and are defined as transmembrane proteins. The activation of these molecules produces a cascade of metabolic reactions that come to influence DNA. Alagille syndrome is a complex pathology, which carries links to an alteration of Jagged's response1; the disease alters, among other pathological signs, the function and morphology of large vessels.

A new protein-coding, the HECTD1 ubiquitin ligase, has been shown to be essential in the development of the aortic arch, influencing the function of retinoic acid. Its functional alteration causes hypoplasia or pathological changes of the aortic arch.

Inosine 5 'monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) of type 2, deriving from the neural crests is fundamental for the development of large vessels. Its importance derives from its ability to influence the guanine nucleotide synthesis correctly; its dysfunction causes aberrations of the large vessels.

In the Human Gene Mutation Database, it is possible to find all the mutations known about humans and large vessels.

Clinical Significance

The in-depth and thorough knowledge regarding the embryological origin and evolution in adulthood is pivotal in understanding the pathophysiology of various congenital and acquired anomalies and enables physicians to initiate the treatment in the most accurate fashion. Integration of embryology in the medical curricula with the assistance of cutting-edge technology is also essential as it is associated with better patient outcomes.[10]

Media

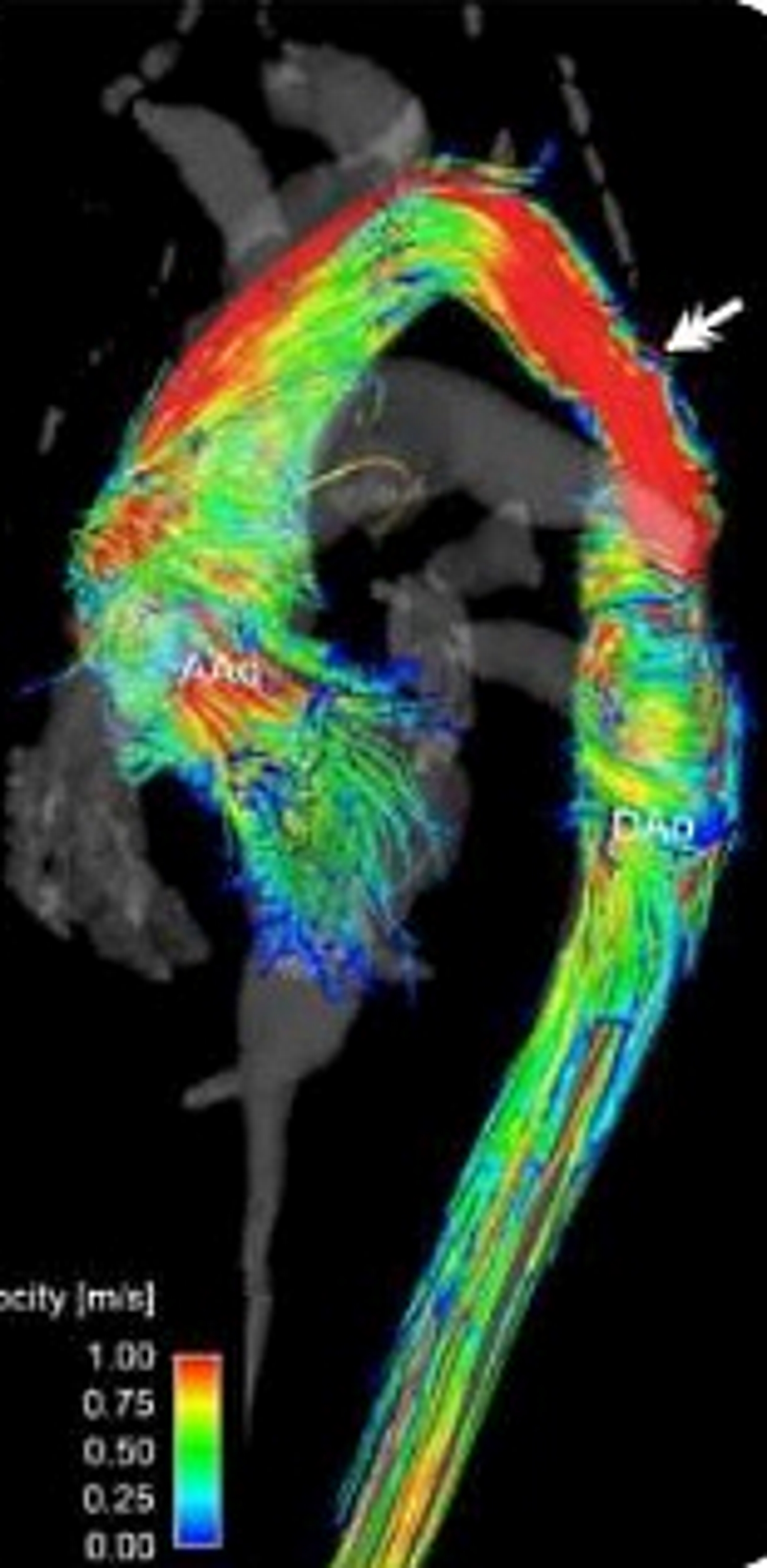

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Computerized angio-tomographic showing coarctation of the aorta. The alteration of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), in particular hypervariable segments 1-4 (HV1-3) can cause alterations in the development of the aortic arch, leading to an aortic coarctation and/or Bovine aortic arch. Contributed by Bruno Bordoni, PhD

References

EDWARDS JE. Anomalies of the derivatives of the aortic arch system. The Medical clinics of North America. 1948 Jul:32():925-49 [PubMed PMID: 18877614]

Türkvatan A,Büyükbayraktar FG,Olçer T,Cumhur T, Congenital anomalies of the aortic arch: evaluation with the use of multidetector computed tomography. Korean journal of radiology. 2009 Mar-Apr [PubMed PMID: 19270864]

Onwuka E, King N, Heuer E, Breuer C. The Heart and Great Vessels. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2018 Mar 1:8(3):. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a031922. Epub 2018 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 28289246]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVANMIEROP LH,ALLEY RD,KAUSEL HW,STRANAHAN A, PATHOGENESIS OF TRANSPOSITION COMPLEXES. I. EMBRYOLOGY OF THE VENTRICLES AND GREAT ARTERIES. The American journal of cardiology. 1963 Aug [PubMed PMID: 14047494]

Cantador AA,Siqueira DED,Guillaumon AT, Anomaly in the Embryogenesis of the Aorta associated with Subclavian Steal Phenomenon. Annals of vascular surgery. 2019 Oct [PubMed PMID: 31200064]

Bhatia A, Shatanof RA, Bordoni B. Embryology, Gastrointestinal. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725857]

Agarwal S, Pangtey B, Vasudeva N. Unusual Variation in the Branching Pattern of the Celiac Trunk and Its Embryological and Clinical Perspective. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2016 Jun:10(6):AD05-7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19527.8064. Epub 2016 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 27504274]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHegazy AA, Anatomy and embryology of umbilicus in newborns: a review and clinical correlations. Frontiers of medicine. 2016 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 27473223]

Jordan JA, Burns B. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Hip Arteries. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194331]

Upson-Taboas CF,Montoya R,O'Loughlin VD, Impact of cardiovascular embryology animations on short-term learning. Advances in physiology education. 2019 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 30615476]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence