Introduction

An esophageal stricture refers to the abnormal narrowing of the esophageal lumen; it often presents as dysphagia, commonly described by patients as difficulty swallowing. It is a serious sequela to many different disease processes and underlying etiologies. Its recognition and management should be prompt. Stricture formation can be due to inflammation, fibrosis, or neoplasia involving the esophagus and often posing damage to the mucosa and/or submucosa.

The esophagus loses distensibility with stricture formation, and this may be localized or diffuse throughout the length of the esophagus. The luminal stricture itself may have abrupt or tapered margins. Recent advancement in the use of endoscopic procedures for diagnostic as well as therapeutic purposes has increased the occurrence of iatrogenic post-procedural esophageal stricture formation resulting from the mucosal injury.

Generally, the term esophageal stricture is reserved for intraluminal esophageal disorders resulting in narrowing, although extrinsic esophageal compression and luminal compromise can sometimes occur by direct invasion of malignancy or lymph node enlargement, for example, and therefore result in esophageal stricture as well. Regardless of etiology, stricture disease is best managed promptly and aggressively to restore luminal patency; this is done for symptomatic improvement and/or palliative management in cases of cancer. New technological advancements in endoscopic therapy and different stent products have shown promising results with notable improvement in stricture management with low recurrence rates and fewer complications.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A stricture is either benign or malignant. Appropriate management depends on identifying the correct etiology for stricture. The majority of esophageal strictures result from benign peptic strictures from long-standing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which accounts for 70 to 80% of adult cases.[1] Early and preventive use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) has somewhat decreased the incidence of such peptic strictures. In addition to chronic poorly controlled acid reflux disease, other etiologies for esophageal stricture development exist. In young children and adolescent populations, corrosive substance ingestion is the leading cause of stricture formation in the esophagus.[2] The following classification and list of common and uncommon causes for stricture formation in the esophagus can guide physicians in their approach to management:

Benign Strictures

- Corrosive substance ingestion: Accidental ingestion of, or suicidal poisoning with, household cleaning products are not uncommon occurrences. Exposure to these corrosive substances is one of the top five most common causes of poisoning in adults and children below five years of age, according to data from the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC).[3] Substance ingestion could cause anything from mild injury to extensive full-thickness necrosis of the esophagus. Stricture development is a common consequence of ingesting such as toxic substances.[4][5]

- Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE): It represents a distinct chronic, local immune-mediated esophageal disease clinically characterized by dysphagia and histologically by eosinophilic-predominant inflammation.[6][7] Due to the chronicity of this condition and the recent rise in the prevalence of the disease, it contributes to a significant number of cases of esophageal strictures.[8] The prevalence of esophageal stricture disease increases with diagnostic delay in EoE (From 17% at 0 to 2 years to 71% at over 20 years), given the time-dependent fibrotic features of EoE the correlate with the duration of untreated disease.[9]

- Drug-induced esophagitis: Many medications can cause pill-induced esophagitis. Common culprits include NSAIDs, potassium chloride tablets, and tetracycline antibiotics, among other medications. Frequently the initial symptoms are self-limiting, and therefore the patient continues with medication usage and is exposed persistently to the drug, causing esophagitis.[10][11] This situation could lead to severe complications such as esophageal stricture in a small percentage of patients.

- Radiation injury: Radiation therapy, when offered alone or combined with surgery, can cause esophageal stricture as a side effect. Radiation is an integral part of head and neck cancer and lung cancer treatment. Radiation targeting the cervical or thoracic regions can cause damage to the surrounding normal soft tissue and result in one of the most common late complications (median duration of 6 months) called radiation-induced esophageal stricture (RIES).[12] The risk of stricture increases substantially with a higher dose of radiation.[13]

- Iatrogenic stricture post-endoscopic therapy: Upper GI endoscopy is commonly an option for diagnostic and therapeutic interventions involving the esophagus. A routine biopsy may be performed in cases of suspected Barrett esophagus or malignancy. Therapeutically, the endoscopic mucosal and submucosal resections of superficial esophageal malignancy are other possibilities. A side effect of these interventions includes damage to the underlying regenerative cell layer, leading to fibrosis and stricture formation. The risk of stricture increases with extensive circumferential resection.[14]][15]

- Anastomotic Stricture: Certain early-stage esophageal cancers and head & neck cancers are managed with an esophagectomy with a high end-esophagogastrostomy or bowel loop interposition. Such procedures have a postoperative risk of anastomotic stricture formation at the anastomosis; this can occur in 22 to 50% of cases and often require repeat endoscopic interventions to dilate the stricture due to high recurrence rates.[16]][17]

- Chemotherapy-induced esophageal stricture: Stricture occurrence related to chemotherapy is rare, and there are few case reports.[18] In pediatric patients, it is reported as a rare event and a result of chemotherapy treatment, but it has been described to possibly have a multifactorial etiology, including infectious and inflammatory factors causing esophagitis.[19]

- Thermal Injury: This is a rare cause of stricture formation in patients who accidentally drink hot edible foods and fluids, especially coffee or tea. The majority of these cases respond to conservative management successfully. A small number of published case reports, where esophageal strictures developed after accidental ingestion of hot substances, described the need for endoscopic dilation or surgical correction to manage the strictures.[20]

- Infectious Esophagitis: Viral infections with cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex (HSV), human immune deficiency virus (HIV) and fungal infections with Candida can cause esophageal mucosal inflammation and stricture formation. They tend to occur in immunocompromised patients, and odynophagia is usually present.

- Other Rare Etiologies:[21][22]

- Prolonged use of nasogastric tube

- Collagen vascular diseases such as scleroderma or SLE.

- Benign mucosal pemphigoid

- Graft versus host disease

- Esophageal web in Plummer-Vinson syndrome.

- Crohn disease

- Tuberculosis

Malignant Stricture

- Esophageal adenocarcinoma

- Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Metastatic esophageal neoplasm - usually from lung cancer

Epidemiology

Esophageal stricture formation is not common. There is an overall low disease prevalence for the condition. One study reported an incidence rate of 1.1 per 10000 person-years, which also increases with age. Peptic strictures, being the most common among them, have decreased in incidence from 1994 to 2000 along with a substantial increase in PPI use during this time. History of GERD, hiatal hernia, prior dysphagia, peptic ulcer disease, and use of alcohol are known risk factors for peptic stricture formation.

Esophageal strictures can occur in any age group or population when one considers all the different possible etiologies. Strictures due to caustic esophagitis or eosinophilic esophagitis, however, are more common in children and young patients. Strictures related to acid reflux, iatrogenic or drug-induced esophagitis, on the other hand, are more common in adults. Malignant strictures are found in older people, as cancer prevalence is higher in older populations.

Peptic strictures are tenfold more common in Whites than Blacks or Asians. There is no clear association between sex genotype and esophageal stricture, but men are at higher risk than women for erosive esophagitis.[23]

Pathophysiology

The normal esophagus measures up to 30 mm in diameter. A stricture can narrow this down to 13 mm or less, causing dysphagia. The pathophysiology of stricture development differs based on the underlying etiology, but the basic pathological changes include damage to the mucosal lining. Over time, this leads to chronic inflammatory changes in the wall of the esophagus. Chronic esophagitis progresses even further with subsequent development of intramural fibrosis and scarring, leading to luminal constriction.

In peptic stricture, these pathophysiological changes happen due to exposure of the esophageal mucosa to refluxed acid-peptic content from the stomach. This reflux can exacerbate with the weakening of the lower esophageal sphincter or impaired esophageal motility, or both.[24] Hiatal hernia contributes significantly as an independent risk factor in the pathophysiology of peptic strictures, given that hiatal hernia presents in 85% of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease with a stricture. Delayed gastric emptying and excessive pepsin secretion could contribute to the process, but these suggested factors lack good evidence for confirmation.

Similarly, most of all other benign strictures result from chronic, long-standing esophagitis secondary to different causes, as described in the section on etiology above.

Malignant stricture develops from intrinsic direct proliferation and invasion of cancer cells from the luminal mucosa. Adenocarcinoma commonly arises from the lower part of the esophagus, and squamous cell carcinoma frequently occurs in the middle and upper parts of the esophagus. Very rarely, the direct growth of lung tumor mass or mediastinal lymph node enlargement can also produce stricture.

History and Physical

Regardless of the nature of the stricture, patients typically present with one or all of the following symptoms: dysphagia, food impaction, odynophagia, chest pain, and weight loss.[25] The most relevant symptom is progressive dysphagia to solid food, and this sometimes progresses to involve semisolid and liquid foods. The rate and type of symptom progression correlate with the underlying type of stricture. Physical examination findings are usually not significant in these patients.

Benign stricture follows a slow and insidious course, while malignant stricture develops rapidly. Sometimes dysphagia is combined with pain in the presence of acute esophagitis. Food impaction requires instant recognition and prompt management to avoid severe complications like aspiration or perforation. Patients presenting with such clinical symptoms have an underlying stricture in about 45% of cases diagnosed at endoscopy.[26]

A careful clinical evaluation, including a directed history and physical examination, can suggest information about the underlying cause of a suspected or endoscopically diagnosed stricture. The physician should gather information about dysphagia pertaining to its nature, duration, onset, severity, and associated symptoms such as heartburn, vomiting, pain while swallowing, any upper respiratory symptoms, or chest pain. Sometimes the patient may report having water brash, morning soreness of throat, or asthma-like wheezing, which may be due to severe regurgitation. In the case of peptic stricture, weight loss is uncommon, and a good appetite is usually present. Weight loss and anorexia, along with long-standing weakness, are more associated with malignant strictures or refractory strictures.[23] The following historical information can also help understand the cause of stricture formation and guide management:[27]

- Known medical history of GERD, Barrett esophagus, hiatal hernia, or medication use that could cause peptic ulcers and GI irritations; any of these are risk factors for peptic stricture.

- The patient has a history of recent caustic product ingestion.

- A prior history of endoscopic treatment or esophageal surgery for any esophageal pathology. Such patients are at risk for developing anastomotic or iatrogenic stricture.

- There is a history of radiation therapy for any prior head & neck or chest malignancy.

- A history of medication use, including alendronate, tetracycline or other antibiotics, NSAIDs, and many others that predispose one to pill-induced esophagitis.

Evaluation

Once a thorough medical history and bedside evaluation are complete, and there is suspicion of esophageal stricture, the next best investigation would be an esophagogastroduodenoscopy or contrast-enhanced esophagogram. Both are principal diagnostic modalities for esophageal stricture. Depending on the severity of dysphagia and the presence of other clinical symptoms, an X-ray of the chest (PA and lateral views) may be acquired to assess for problems such as foreign body impaction or diaphragmatic hernia and rule out some other pulmonary conditions. Sometimes a CT scan is more helpful in patients with a history of caustic substance ingestion to rule of esophageal perforation. However, X-ray and CT imaging are not necessary in routine cases. CT is helpful in a patient who is found to have a malignant stricture on biopsy and helps with disease staging.

The majority of the patients are evaluated by endoscopy since it can provide overall information on esophageal anatomy and establish not just the diagnosis of a stricture but also allow for biopsy of the mucosa. Endoscopy affords an opportunity for therapeutic dilation of the stricture when indicated. Contrast fluoroscopy is only for those patients who have a complex stricture or when endoscopy is incomplete due to excessive narrowing of the lumen. Choosing a water-soluble contrast agent for first-pass viewing is advised here to avoid inspissation of heavy agents such as barium and thereby minimizing the risk for obstruction and/or aspiration.

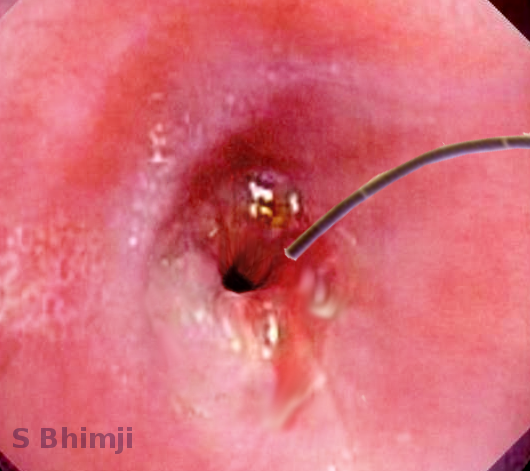

UGI Endoscopy

Upper GI endoscopy is the most important diagnostic and therapeutic intervention in the case of a stricture. After the presence of a stricture is confirmed, the most important step is to biopsy the stricture to rule out malignancy. Differentiation of benign stricture from malignant stricture is absolutely necessary to guide further management approaches. Endoscopy not only allows for the biopsy but it also visualizes the area around the stricture for any mass or lesions. Benign esophageal strictures classify as simple or complex strictures based on the size, involved area, surface, luminal narrowing, and margins. Simple strictures are usually under 2 cm in size, straight, and allow easy passage for the endoscope. Complex strictures, on the other hand, are typically longer than 2 cm, have an uneven surface, tortious margins, and a narrow diameter. Complex strictures are difficult to manage and require additional fluoroscopy or advanced thin-caliber endoscopes for further assessment.[28]

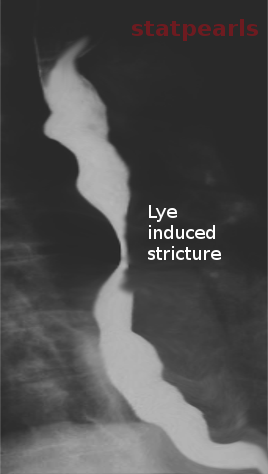

Barium Contrast Swallow

It can show the abnormality in the esophagus and provide an understanding of the level, size, extent, and severity of strictures, especially when standard endoscopes cannot pass through the stricture and thin-caliber scopes are not available. Barium contrast swallows are found to have 95% sensitivity for diagnosing esophageal stricture. The radiographic appearance of a stricture differs based on the underlying etiology.[29][30] Water-soluble contrast is used in patients with suspected perforation or to get a first image before passing barium. Currently, barium contrast fluoroscopy is the recommended first-line investigation in patients with suspected complex strictures, such as patients having a history of radiation therapy or a history of caustic substance ingestion.[31]

Endoscopic Ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can provide high-resolution images of the esophageal wall, and it can provide detailed information about the extent of the esophageal injury in other benign causes of stricture. Sometimes multiple biopsy specimens of stricture are non-conclusive. These cases can also have normal mucosa with CT also showing only wall thickening. They pose difficult challenges for diagnosis. In such cases, EUS can provide critical information. Patients with malignant esophageal strictures have a thicker esophageal wall on EUS, with a loss of wall stratification compared to patients with benign esophageal strictures, who demonstrate preservation of wall stratification more frequently. With EUS, suspected malignancy cases could benefit from identification and elective surgical resection rather than offering resection to all cases, including indeterminate ones.[32]

Treatment / Management

Any stricture requires treatment to establish adequate luminal patency. Various methods and instruments are used to achieve this goal. Treatments include the use of dilators, stent placement, surgical resection, and medical management. The technique most utilized for benign stricture management is endoscopic dilation using a bougie or a balloon dilator. The main objective is to improve symptoms, mainly in relieving patients of dysphagia.[33] In clinical practice, treatment outcome is evaluated by a dysphagia scoring system. Ogilvie et al. first introduced such a scoring system, but they applied it in the context of esophageal malignancy palliated with stent placement to relieve dysphagia. However, it has application to almost all types of benign and malignant stricture management situations.[34] The following describes the clinical dysphagia scoring system:

Score:

- 0 - No dysphagia: able to eat a normal diet.

- 1 - Moderate passage: able to eat some solid foods.

- 2 - Poor passage: able to eat only semi-solid foods.

- 3 - Very poor passage: able to swallow only liquids only.

- 4 - No passage: unable to swallow anything.

Upon establishing the type of stricture, the dilation management plan involves the following considerations:

- Selection of appropriate dilation technique

- The need for adjunctive methods

- The safe level of dilation

Benign strictures commonly receive treatment with endoscopic dilators followed by disease-specific management approaches to treat the underlying inflammatory process.[35]

Esophageal Stricture Dilation

Dilator Selection

There are currently two main types of dilators in use in clinical practice. Each has its own advantage and disadvantage.[36](A1)

- Mechanical (push type or bougie): They come with a variety of sizes and are made up of different types of materials such as rubber. Maloney bougie dilator can be freely passed without the use of the guidewire. While Savary-Gilliard has a guidewire to assist in the passage.

- Balloon: Expansion of a balloon produces radial force to dilate the lumen. Different sizes are available, and a balloon dilator gets passed through the scope (TTS).[37] Newer balloon dilators from having an inbuilt guidewire and also allow for three different size expansions without changing the balloon. (B3)

Stricture dilation is an ambulatory outpatient procedure that requires certain levels of expertise from an endoscopist.[38] Appropriate selection of dilator is determined usually based on the complexity, size, and site of the stricture. A lower esophageal stricture is commonly peptic in nature; due to their simple characteristic and small size, mechanical dilators are safe and effective in treating them. Complex strictures tend to undergo management with balloon dilators.

Technique

First, the size of the dilator that is going to be used is estimated endoscopically by assessing the diameter of the stricture area. The first dilation performed should be the same size as the stricture. It is advanced in increments. No excessive force is used. The majority of surgeons or endoscopists follow the “rule of three,” performing up to three dilations per session while successively increasing the diameter of the dilator by 2 mm (6Fr).[39][31][40] The use of fluoroscopy is controversial, but can certainly be helpful in complex strictures. It can play a contributory role based on the endoscopist’s experience.[41][42](B2)

Use of Adjunctive Methods

At present two main adjunctive treatment methods are employed based on preference: Intra-lesion injection of steroid, or oral steroid gel use, and endoscopic stricturoplasty. Steroids help in decreasing the inflammation related to injury from dilation and, hence, reduce the chance of restenosis. However, long-term data are needed to establish its standard use.[43] Other studies have shown better outcomes based on the lower recurrence of stenosis and the achievement of larger diameter patency.[44] Four-quadrant stricturoplasty can be one option to consider in highly fibrotic strictures.(A1)

Long-term success with dilation can often be challenging to achieve in all cases of stricture. Unfavorable outcomes are more common in strictures from corrosive injury. Dilation is successful in only about 25% of such cases. Successful outcomes here refer to the ability to swallow solid food without intervention for 6 months after the first procedure.[45]

The major problem one faces in stricture management is a recurrence. A stricture is recurrent when there is an inability to maintain a satisfactory luminal diameter for 4 weeks after achieving the target diameter of 14 mm. A stricture is refractory when there remains a persistent dysphagia score of 2 or more, as a result of an inability to successfully achieve a diameter of 14 mm over five sessions of dilation done at 2-week intervals.[46](B3)

Esophageal Stents

Stents are often reserved for malignant stricture and refractory benign strictures. The goal of stent placement is to hold the stricture open for prolonged periods, causing the stricture, or the tissue around it, to remodel so that the stricture does not recur after stent removal. In malignant stricture, this could be either used for complete palliation in case of advanced cancer or temporary palliation in cases of ongoing neoadjuvant treatment.[47][48]

Stents are the breakthrough inventions considering the extent of benefits they can provide in terms of symptom improvement and quality of life enhancement, especially in patients who are suffering from terminal cancer. Over the years, esophageal stents have evolved from rigid plastic conduits to self-expanding metal stents (SEMS). Improvements continued to address the disadvantages of previous models. This trend is notable with SEMS, where initially non-covered stents were the initial offering. Later, partially and then fully covered stents were developed to correct the issue of epithelialization and tumor growth in the previous older uncovered SEMS, allowing feasibility of stent removal. Covered stents, however, show a higher displacement rate (20%) compared to there metal counterparts. To resolve this, biodegradable stents and suture fixation techniques are under clinical evaluation, and initial evidence shows promising outcomes.[49][50][51][52] Biodegradable stents show superiority in outcomes and symptomatic improvements in patients with a corrosive esophageal stricture.[53](B2)

Benefits, safety, and feasibility of different stents have undergone comparison in various clinical and randomized controlled trials. Currently, no clear outcome benefit is apparent between the use of partial vs. full covered SEMS for palliative management of malignant strictures in regards to recurrent obstruction and symptomatic success (the COPAC Study).[54] The FDA has approved the use of SEPS (Self-expanding plastic stents) for the indication of benign esophageal stricture.(A1)

Surgical Management

Surgical resection is reserved for malignant disease-causing esophageal stricture or benign conditions recalcitrant to less aggressive forms of medical and/or endoscopic therapy. When surgery is necessary for benign refractory peptic strictures, an antireflux procedure is selectively done to prevent further stenosis.[55] Extensive surgery may be necessary in cases of malignant stricture, where concurrent removal of a mass also takes place if staging is favorable. In such cases, partial or complete esophagectomy, with gastric tube pull-up or bowel loop interposition and anastomosis is performed. Otherwise, palliative surgical approaches are considered to relieve symptoms or obstruction and to provide a route for enteral nutrition distal to a stricture, usually via gastrostomy tube placement.

Differential Diagnosis

In the workup and management of suspected esophageal stricture disease, it is prudent to assess for the concomitant presence of esophageal motility disorders that may influence management. The following conditions are important to consider:

- Diffuse esophageal spasm: with this condition, the esophagus contracts asynchronously, leading to uneven peristalsis. Patients present with mid-chest pain following ingestion of food. They also experience dysphagia, although chest pain is a more common presenting symptom. Esophageal manometry is the most accurate diagnostic test to detect irregular peristalsis. A barium swallow can show abnormal esophageal contractions, and in some cases of the hypercontracted esophagus, also known as nutcracker esophagus, a classic “cork-screw” like appearance may be present.[56]

- Achalasia: in this condition, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) fails to relax properly due to idiopathic or infectious damage to the myenteric plexus of the esophageal wall. With the failure of LES relaxation, food gets stuck at the lower esophagus, causing dysphagia and halitosis. A barium swallow may show a classic bird beak appearance, and this is diagnostic for achalasia in the absence of any pathological abnormality on endoscopic biopsy.[57]

- Pseudo-achalasia: This is similar to achalasia, except the pathophysiology involves neoplastic tumor cell invasion at a lower esophageal wall. An endoscopic biopsy will help to differentiate it from stricture.[58]

- Esophageal cancer: although malignant stricture can form as a serious complication in local thoracic neoplastic masses, sometimes the tumor itself can cause the obstruction of the lumen and cause dysphagia. Endoscopy will help to distinguish this condition.

Prognosis

Esophageal stricture develops over time, and prognosis depends on the timing of evaluation and management and the underlying cause of stricture. While esophageal dilation is the first-line management in cases of benign esophageal stricture, regardless of the underlying cause, it poses a 10 to 30% chance of re-stenosis. Stricture recurrence is the primary concern resulting in added risks and costs. Peptic stricture shows an excellent prognosis when treated promptly with endoscopic dilation and long-term PPI therapy. Surgical correction of a hiatal hernia, if present, produces excellent results with minimal risk for re-stenosis and significant symptomatic improvement.[55] To improve prognosis in terms of decreasing stricture recurrence, concurrent steroid injection therapy or steroid pill therapy have been used and are showing promising clinical outcomes.[43] Stent placement is kept reserved for benign stricture cases where repeated dilation is not adequate and symptomatic control is poor. In the case of malignant stricture, the prognosis depends on the cancer type, tumor invasion, and disease stage. Surgical resection demonstrates a better prognosis for cancer, which hasn’t yet invaded lymph nodes and surrounding tissue. When stricture management is with stent placement for palliation, the prognosis is almost always poor.

Complications

Untreated esophageal stricture related complications:

- Food impaction

- Food particle aspiration

- Asthma from aspiration

- Severe chest pain

- Esophageal perforation from long-standing inflammation

- Fistula formation

Iatrogenic complication from stricture dilation and stent placement:[59][60]

- Esophageal perforation

- Bleeding

- Hemorrhage

- Anesthesia-related complications (such as respiratory failure, sedation)

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Bacteremia - 22% of cases develop transient bacteremia from esophageal dilation

- It is usually associated with malignant stricture dilation and multiple dilations

- Periprocedural antibiotics are usually recommended to avoid this

- Re-stricture formation

- New stricture formation

- Traumatic stent removal

- Epithelization of the uncovered stent

- Displacement of stent proximally which could potentially cause choking sensation and difficulty in breathing

Deterrence and Patient Education

Stricture is a complicated disease process and requires a thorough understanding and cooperation from patients for adequate management. The patient should know the potential complications which could happen during the stricture treatment since they could be more severe, involving esophageal perforation and bleeding. Patients should receive education about the long-term management of the underlying disease process and chances of recurrence and regarding seeking immediate medical attention when symptoms like dysphagia, regurgitation recur. Patients should receive immediate attention when they are diagnosed with any of the etiologies which could cause stricture about preventive therapies to decrease the chances of developing such severe complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

The etiology behind stricture formation can be managed with appropriate treatment modalities to prevent future stricture formation as well as the progression of the pathology. Peptic strictures are best managed with long-term PPI therapy.[61] Eosinophilic esophagitis should undergo a trial of a PPI, as the clinical response to the PPI trial indicates GERD associated eosinophilia rather than eosinophilic esophagitis. If repeat endoscopy still shows eosinophilia, they are diagnosed as true eosinophilic esophagitis and best treated medically with vaporized glucocorticoids such as fluticasone or budesonide. Pill-induced esophageal stricture requires proper measures in regards to pill ingestion. Patients should be advised to take plenty of water while taking pills, take one pill at a time and avoid lying down for 30 min after pill ingestion. Such measures help in preventing further damage to mucosa and recurrence of stricture.[62]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Esophageal stricture is an emergency condition, which requires prompt recognition and management by health care providers in the emergency room or clinic setting. Outcomes are enhanced when primary care teams recognize concerning signs and symptoms and take immediate measures to minimize complications for patients with partial or complete obstruction of the esophagus. Being selective with the diagnostic workup is essential, and appropriate, timely referrals to an endoscopist merit consideration. A solid clinical knowledge base and endoscopic skill level are needed for the endoscopist to successfully diagnose and treat patients who present with dysphagia or other esophageal-related symptoms. In addition to early treatment, stricture requires long-term clinical observation and management to prevent a recurrence. Nursing personnel and pharmacists familiar with the etiologies for esophageal stricture formation can help deliver appropriate treatment and guide patients to seek specialty consultations when needed. Their knowledge of medications that could potentially cause esophagitis and stricture is important in assisting them in modifying care and suggesting preventive measures such as drinking plenty of water and staying upright for a minimum amount of time when taking pills orally. Malignant stricture requires a team approach to management with the involvement of medical, radiation, and surgical oncologists in addition to GI consultants, nutritional specialists, and hospice nursing staff. It is important to recognize that most benign strictures should have initial treatment with endoscopic dilation. If refractory or malignant, they can be candidates for stent placement for palliative relief in individual cases. All interprofessional healthcare team members (physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists) need to communicate across disciplines to achieve optimal clinical outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

References

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Pasha SF, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley KQ, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Sharaf R, Saltzman JR, Shergill AK, Cash B. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of dysphagia. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2014 Feb:79(2):191-201. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.042. Epub 2013 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 24332405]

Lamoria S, De A, Agarwal S, Singh Lamba BM, Sharma V. Peptic esophageal stricture in an adolescent with Barrett's esophagus. International journal of adolescent medicine and health. 2016 Feb 27:29(5):. pii: /j/ijamh.2017.29.issue-5/ijamh-2015-0106/ijamh-2015-0106.xml. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2015-0106. Epub 2016 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 26926861]

Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, McMillan N, Ford M. 2013 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 31st Annual Report. Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2014 Dec:52(10):1032-283. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.987397. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25559822]

Chirica M, Bonavina L, Kelly MD, Sarfati E, Cattan P. Caustic ingestion. Lancet (London, England). 2017 May 20:389(10083):2041-2052. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30313-0. Epub 2016 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 28045663]

Le Naoures P, Hamy A, Lerolle N, Métivier E, Lermite E, Venara A. Risk factors for symptomatic esophageal stricture after caustic ingestion-a retrospective cohort study. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2017 Jun 1:30(6):1-6. doi: 10.1093/dote/dox029. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29207003]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, Burks AW, Chehade M, Collins MH, Dellon ES, Dohil R, Falk GW, Gonsalves N, Gupta SK, Katzka DA, Lucendo AJ, Markowitz JE, Noel RJ, Odze RD, Putnam PE, Richter JE, Romero Y, Ruchelli E, Sampson HA, Schoepfer A, Shaheen NJ, Sicherer SH, Spechler S, Spergel JM, Straumann A, Wershil BK, Rothenberg ME, Aceves SS. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2011 Jul:128(1):3-20.e6; quiz 21-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. Epub 2011 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 21477849]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLucendo AJ, Molina-Infante J, Arias Á, von Arnim U, Bredenoord AJ, Bussmann C, Amil Dias J, Bove M, González-Cervera J, Larsson H, Miehlke S, Papadopoulou A, Rodríguez-Sánchez J, Ravelli A, Ronkainen J, Santander C, Schoepfer AM, Storr MA, Terreehorst I, Straumann A, Attwood SE. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United European gastroenterology journal. 2017 Apr:5(3):335-358. doi: 10.1177/2050640616689525. Epub 2017 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 28507746]

Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Grize L, Bucher KA, Beglinger C, Simon HU. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow-up of 30 adult patients for up to 11.5 years. Gastroenterology. 2003 Dec:125(6):1660-9 [PubMed PMID: 14724818]

Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, Kuchen T, Portmann S, Simon HU, Straumann A. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013 Dec:145(6):1230-6.e1-2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. Epub 2013 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 23954315]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAbid S, Mumtaz K, Jafri W, Hamid S, Abbas Z, Shah HA, Khan AH. Pill-induced esophageal injury: endoscopic features and clinical outcomes. Endoscopy. 2005 Aug:37(8):740-4 [PubMed PMID: 16032493]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKim SH, Jeong JB, Kim JW, Koh SJ, Kim BG, Lee KL, Chang MS, Im JP, Kang HW, Shin CM. Clinical and endoscopic characteristics of drug-induced esophagitis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Aug 21:20(31):10994-9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10994. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25152603]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChoi GB, Shin JH, Song HY, Lee YS, Cho YK, Bae JI, Kim JH, Jeong YH, Park MH. Fluoroscopically guided balloon dilation for patients with esophageal stricture after radiation treatment. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2005 Dec:16(12):1705-10 [PubMed PMID: 16371539]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePark JH, Kim KY, Song HY, Cho YC, Kim PH, Tsauo J, Kim MT, Jun EJ, Jung HY, Kim SB, Kim JH. Radiation-induced esophageal strictures treated with fluoroscopic balloon dilation: clinical outcomes and factors influencing recurrence in 62 patients. Acta radiologica (Stockholm, Sweden : 1987). 2018 Mar:59(3):313-321. doi: 10.1177/0284185117713351. Epub 2017 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 28573925]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMartínek J, Juhas S, Dolezel R, Walterová B, Juhasova J, Klima J, Rabekova Z, Vacková Z. Prevention of esophageal strictures after circumferential endoscopic submucosal dissection. Minerva chirurgica. 2018 Aug:73(4):394-409. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4733.18.07751-9. Epub 2018 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 29795068]

Yang D, Coman RM, Kahaleh M, Waxman I, Wang AY, Sethi A, Shah AR, Draganov PV. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for Barrett's early neoplasia: a multicenter study in the United States. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2017 Oct:86(4):600-607. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.023. Epub 2016 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 27688205]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePark JY, Song HY, Kim JH, Park JH, Na HK, Kim YH, Park SI. Benign anastomotic strictures after esophagectomy: long-term effectiveness of balloon dilation and factors affecting recurrence in 155 patients. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2012 May:198(5):1208-13. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7608. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22528915]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZieren HU, Müller JM, Pichlmaier H. Prospective randomized study of one- or two-layer anastomosis following oesophageal resection and cervical oesophagogastrostomy. The British journal of surgery. 1993 May:80(5):608-11 [PubMed PMID: 8518900]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSedhom D, Sedhom R, Mishra A, Razjouyan H, Rustgi V. Esophageal Stricture Resulting from Systemic Chemotherapy for Solid Malignancy. ACG case reports journal. 2017:4():e99. doi: 10.14309/crj.2017.99. Epub 2017 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 28848771]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKelly K, Storey L, O' Sullivan M, Butler K, McDermott M, Corbally M, McMahon C, Smith OP, O' Marcaigh A. Esophageal strictures during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 2010 Mar:32(2):124-7. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181ced25c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20168244]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKitajima T, Momose K, Lee S, Haruta S, Shinohara H, Ueno M, Fujii T, Udagawa H. Benign esophageal stricture after thermal injury treated with esophagectomy and ileocolon interposition. World journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Jul 21:20(27):9205-9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.9205. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25083096]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoleiro J, Faias S, Afonso A. Esophageal Stricture of an Unusual Etiology. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2016 Jun:14(6):e59-e60. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.006. Epub 2015 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 26598227]

Mbiine R, Kabuye R, Lekuya HM, Manyillirah W. Tuberculosis as a primary cause of oesophageal stricture: a case report. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery. 2018 Jun 5:13(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s13019-018-0743-4. Epub 2018 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 29871658]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRichter JE, Rubenstein JH. Presentation and Epidemiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan:154(2):267-276. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.045. Epub 2017 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 28780072]

Kuo WH, Kalloo AN. Reflux strictures of the esophagus. Gastrointestinal endoscopy clinics of North America. 1998 Apr:8(2):273-81 [PubMed PMID: 9583006]

Smith CD. Esophageal strictures and diverticula. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2015 Jun:95(3):669-81. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2015.02.017. Epub 2015 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 25965138]

Gretarsdottir HM, Jonasson JG, Björnsson ES. Etiology and management of esophageal food impaction: a population based study. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2015 May:50(5):513-8. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.983159. Epub 2015 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 25704642]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKikendall JW. Pill-induced esophagitis. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2007 Apr:3(4):275-6 [PubMed PMID: 21960840]

Shami VM. Endoscopic management of esophageal strictures. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014 Jun:10(6):389-91 [PubMed PMID: 25013392]

Luedtke P, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Weinstein DS, Laufer I. Radiologic diagnosis of benign esophageal strictures: a pattern approach. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2003 Jul-Aug:23(4):897-909 [PubMed PMID: 12853664]

Karasick S, Lev-Toaff AS. Esophageal strictures: findings on barium radiographs. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1995 Sep:165(3):561-5 [PubMed PMID: 7645471]

Sami SS, Haboubi HN, Ang Y, Boger P, Bhandari P, de Caestecker J, Griffiths H, Haidry R, Laasch HU, Patel P, Paterson S, Ragunath K, Watson P, Siersema PD, Attwood SE. UK guidelines on oesophageal dilatation in clinical practice. Gut. 2018 Jun:67(6):1000-1023. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315414. Epub 2018 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 29478034]

Rana SS, Sharma R, Gupta R. High-frequency miniprobe endoscopic ultrasonography for evaluation of indeterminate esophageal strictures. Annals of gastroenterology. 2018 Nov-Dec:31(6):680-684. doi: 10.20524/aog.2018.0307. Epub 2018 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 30386117]

Standards of Practice Committee, Egan JV, Baron TH, Adler DG, Davila R, Faigel DO, Gan SL, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, Lichtenstein D, Qureshi WA, Rajan E, Shen B, Zuckerman MJ, VanGuilder T, Fanelli RD. Esophageal dilation. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2006 May:63(6):755-60 [PubMed PMID: 16650533]

Ogilvie AL, Dronfield MW, Ferguson R, Atkinson M. Palliative intubation of oesophagogastric neoplasms at fibreoptic endoscopy. Gut. 1982 Dec:23(12):1060-7 [PubMed PMID: 6184269]

Dakkak M, Hoare RC, Maslin SC, Bennett JR. Oesophagitis is as important as oesophageal stricture diameter in determining dysphagia. Gut. 1993 Feb:34(2):152-5 [PubMed PMID: 8432464]

Cox JG, Winter RK, Maslin SC, Dakkak M, Jones R, Buckton GK, Hoare RC, Dyet JF, Bennett JR. Balloon or bougie for dilatation of benign esophageal stricture? Digestive diseases and sciences. 1994 Apr:39(4):776-81 [PubMed PMID: 7818628]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTaub S, Rodan BA, Bean WJ, Koerner RS, Mullin DM, Feng TS. Balloon dilatation of esophageal strictures. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1986 Jan:81(1):14-8 [PubMed PMID: 3942119]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAbele JE. The physics of esophageal dilatation. Hepato-gastroenterology. 1992 Dec:39(6):486-9 [PubMed PMID: 1483657]

Tulman AB, Boyce HW Jr. Complications of esophageal dilation and guidelines for their prevention. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 1981 Nov:27(4):229-34 [PubMed PMID: 7030864]

Spechler SJ. AGA technical review on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1999 Jul:117(1):233-54 [PubMed PMID: 10381933]

Raymondi R, Pereira-Lima JC, Valves A, Morales GF, Marques D, Lopes CV, Marroni CA. Endoscopic dilation of benign esophageal strictures without fluoroscopy: experience of 2750 procedures. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2008 Jul-Aug:55(85):1342-8 [PubMed PMID: 18795685]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePereira-Lima JC, Ramires RP, Zamin I Jr, Cassal AP, Marroni CA, Mattos AA. Endoscopic dilation of benign esophageal strictures: report on 1043 procedures. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1999 Jun:94(6):1497-501 [PubMed PMID: 10364013]

Yan X, Nie D, Zhang Y, Chang H, Huang Y. Effectiveness of an orally administered steroid gel at preventing restenosis after endoscopic balloon dilation of benign esophageal stricture. Medicine. 2019 Feb:98(8):e14565. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014565. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30813172]

Ramage JI Jr, Rumalla A, Baron TH, Pochron NL, Zinsmeister AR, Murray JA, Norton ID, Diehl N, Romero Y. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of endoscopic steroid injection therapy for recalcitrant esophageal peptic strictures. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2005 Nov:100(11):2419-25 [PubMed PMID: 16279894]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTharavej C, Pungpapong SU, Chanswangphuvana P. Outcome of dilatation and predictors of failed dilatation in patients with acid-induced corrosive esophageal strictures. Surgical endoscopy. 2018 Feb:32(2):900-907. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5764-x. Epub 2017 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 28733733]

Kochman ML, McClave SA, Boyce HW. The refractory and the recurrent esophageal stricture: a definition. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2005 Sep:62(3):474-5 [PubMed PMID: 16111985]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSharma P, Kozarek R, Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology. Role of esophageal stents in benign and malignant diseases. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2010 Feb:105(2):258-73; quiz 274. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.684. Epub 2009 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 20029413]

Hindy P, Hong J, Lam-Tsai Y, Gress F. A comprehensive review of esophageal stents. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2012 Aug:8(8):526-34 [PubMed PMID: 23293566]

Repici A, Vleggaar FP, Hassan C, van Boeckel PG, Romeo F, Pagano N, Malesci A, Siersema PD. Efficacy and safety of biodegradable stents for refractory benign esophageal strictures: the BEST (Biodegradable Esophageal Stent) study. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2010 Nov:72(5):927-34. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.07.031. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21034894]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKantsevoy SV, Bitner M. Esophageal stent fixation with endoscopic suturing device (with video). Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2012 Dec:76(6):1251-5. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.08.003. Epub 2012 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 23031249]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLi X, Zhang W, Zhang G. Endoscopic suturing device with Overstitch for esophageal stent fixation. Digestive endoscopy : official journal of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. 2019 Jan:31(1):e3-e4. doi: 10.1111/den.13268. Epub 2018 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 30153347]

Imaz-Iglesia I, García-Pérez S, Nachtnebel A, Martín-Águeda B, Sánchez-Piedra C, Karadayi B, Demirbaş AR. Biodegradable stents for the treatment of refractory or recurrent benign esophageal stenosis. Expert review of medical devices. 2016 Jun:13(6):583-99. doi: 10.1080/17434440.2016.1184967. Epub 2016 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 27152556]

Karakan T, Utku OG, Dorukoz O, Sen I, Colak B, Erdal H, Karatay E, Tahtaci M, Cengiz M. Biodegradable stents for caustic esophageal strictures: a new therapeutic approach. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2013 Apr:26(3):319-22. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01418.x. Epub 2012 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 22974043]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDidden P, Reijm AN, Erler NS, Wolters LMM, Tang TJ, Ter Borg PCJ, Leeuwenburgh I, Bruno MJ, Spaander MCW. Fully vs. partially covered selfexpandable metal stent for palliation of malignant esophageal strictures: a randomized trial (the COPAC study). Endoscopy. 2018 Oct:50(10):961-971. doi: 10.1055/a-0620-8135. Epub 2018 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 29895072]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePregun I, Hritz I, Tulassay Z, Herszényi L. Peptic esophageal stricture: medical treatment. Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2009:27(1):31-7. doi: 10.1159/000210101. Epub 2009 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 19439958]

Frieling T. Non-Cardiac Chest Pain. Visceral medicine. 2018 Apr:34(2):92-96. doi: 10.1159/000486440. Epub 2018 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 29888236]

Swanström LL. Achalasia: treatment, current status and future advances. The Korean journal of internal medicine. 2019 Nov:34(6):1173-1180. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.439. Epub 2019 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 30866609]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLawal A, Antonik S, Dua K, Massey BT. Esophageal adenocarcinoma: pseudo-nutcracker esophagus. Dysphagia. 2009 Jun:24(2):234-7. doi: 10.1007/s00455-008-9175-y. Epub 2008 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 18626696]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWesdorp IC, Bartelsman JF, den Hartog Jager FC, Huibregtse K, Tytgat GN. Results of conservative treatment of benign esophageal strictures: a follow-up study in 100 patients. Gastroenterology. 1982 Mar:82(3):487-93 [PubMed PMID: 7054043]

Nelson DB, Sanderson SJ, Azar MM. Bacteremia with esophageal dilation. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 1998 Dec:48(6):563-7 [PubMed PMID: 9852444]

Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013 Mar:108(3):308-28; quiz 329. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444. Epub 2013 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 23419381]

Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA, American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013 May:108(5):679-92; quiz 693. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71. Epub 2013 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 23567357]