Introduction

Inguinal hernia repair is an extremely common operation performed by surgeons. More than 800,000 repairs performed annually. An inguinal hernia is an opening in the myofascial plain of the oblique and transversalis muscles that can allow for herniation of intraabdominal or extraperitoneal organs. These groin hernias can be divided into indirect, direct, and femoral based on location. Most patients present with a bulge or pain in the groin. Healthcare professionals recommend repairing all symptomatic hernias to avoid complications. An open or laparoscopic approach can be used with the goal of defect closure and a tension-free repair. A mesh is usually used for a tension-free repair. When the mesh is contraindicated, primary suture repair can be performed.[1][2][3][4][5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Inguinal hernias are considered to have both a congenital and acquired component. Most adult hernias are considered acquired. However, there is evidence to suggest genetics also play a role. Patients with a known family history of a hernia are at least 4 times more likely to have an inguinal hernia than patients with no known family history. Studies have also shown that certain diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Marfan syndrome contribute to increased incidence of an inguinal hernia. Also, it is believed that increased intra-abdominal pressure, as seen in obesity, chronic cough, heavy lifting, and straining due to constipation, also plays a role in the development of an inguinal hernia.

Epidemiology

Inguinal hernia repair is a common surgery in the United States. It is estimated that about 800,000 inguinal hernias are performed annually. Inguinal hernias account for 75% of all abdominal wall hernias. The incidence of inguinal hernias has a bimodal distribution, with peaks around age 5 and after age 70. Two-thirds of these hernias are indirect, making an indirect hernia the most common groin hernia in both males and females. Males account for about 90% of all inguinal hernias and females about 10%. Femoral hernias account for only 3% of all inguinal hernias and are more commonly seen in women with females accounting for about 70% of all femoral hernias. An inguinal hernia will affect nearly 25% of men and less than 2% of women over their lifetime. An indirect hernia occurs more often on the right. This is believed to be attributed to the slower closure of a patent processus vaginalis on the right side compared to the left.

Pathophysiology

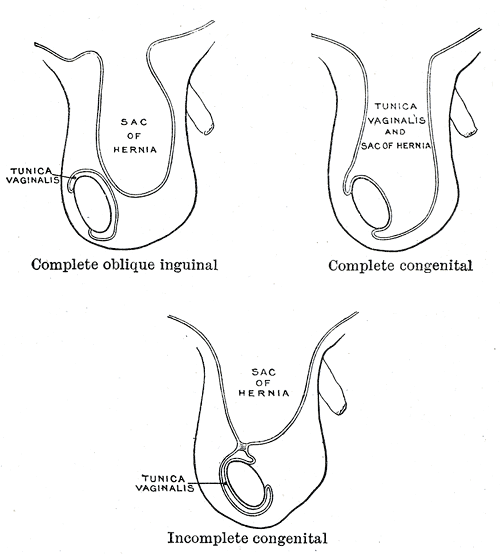

Studies have shown that inguinal hernia patients have demonstrated higher proportions of type III collagen as compared to type I. Type I collagen is associated with better tensile strength than type III. Studies have also shown that a patent processus vaginalis predisposes to the development of an inguinal hernia in adulthood. The majority of pediatric inguinal hernias are thought to be congenital due to a patent processus vaginalis. During normal development, the testes descend from the abdomen into the scrotum leaving behind a diverticulum that protrudes through the inguinal canal and becomes the processus vaginalis. In normal development, the processus vaginalis closes around 40 weeks of gestation eliminating the peritoneal opening at the internal ring. Failure of this closure can lead to an indirect hernia in the pediatric population. A patent processus vaginalis does not always lead to an inguinal hernia.

History and Physical

Inguinal hernias can present with an array of different symptoms. Most patients present with a bulge in the groin area, or pain in the groin. Some will describe the pain or bulge that gets worse with physical activity or coughing. Symptoms may include a burning or pinching sensation in the groin. These sensations can radiate into the scrotum or down the leg. It is important to perform a thorough physical and history to rule out other causes of groin pain. At times an inguinal hernia can present with severe pain or obstructive symptoms caused by incarceration or strangulation of the hernia sac contents.[6][7][8][9]

A proper physical exam is essential in the diagnosis of an inguinal hernia. Physical examination is the best way to diagnose a hernia. The exam is best performed with the patient standing. Visual inspection of the inguinal area is conducted first to rule out obvious bulges or asymmetry in groin or scrotum. Next, the examiner palpates over the groin and scrotum to detect the presence of a hernia. The palpation of the inguinal canal is completed last. The examiner palpates through the scrotum and towards the external inguinal ring. The patient is then instructed to cough or perform a Valsalva maneuver. If a hernia is present, the examiner will be able to palpate a bulge that moves in and out as the patient increases intraabdominal pressure through coughing or Valsalva. Examination of the contralateral side is essential as this allows the clinician to compare right versus left for symmetry and/or abnormalities. It is not essential to differentiate an indirect from a direct hernia on the exam as the surgical repair is the same for both. A femoral hernia should be palpable below the inguinal ligament and just lateral to the pubic tubercle. Femoral hernias can easily be missed in an obese patient. In cases when there is high suspicion but no hernia can be detected on physical exam, a radiologic investigation may be warranted to elicit the diagnosis.

Evaluation

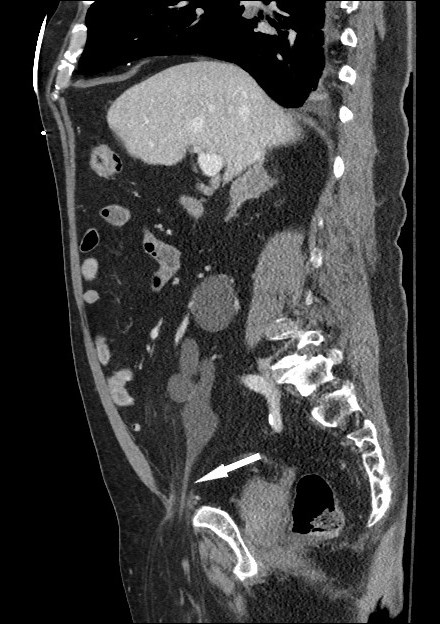

Most inguinal hernias are diagnosed with a thorough history and physical examination. When history strongly suggests a hernia, but none can be elicited on an exam or in situations where body habitus makes physical examination limited, then a radiologic investigation may be warranted. Radiologic modalities include ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An ultrasound is the least invasive modality, but it is largely dependent on the skill of the examiner. The examination should be conducted with a Valsalva maneuver to increase intra-abdominal pressure. An ultrasound can detect an inguinal hernia with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 77%. CT imaging is beneficial when the diagnosis is obscure. CT scan can better delineate groin anatomy and help to detect other etiologies of groin mass or in cases of complicated hernias. CT scan can detect inguinal hernias with a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 65%. MRI has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 96% in the detection of an inguinal hernia. However, MRI is costly and rarely used for diagnosis of an inguinal hernia due to its limited access. When indicated, MRI can be used to assist in the differentiation of sports-related injuries versus inguinal hernias.

Treatment / Management

Surgical Repair

Surgical repair is the definitive treatment for an inguinal hernia. As a general rule, all symptomatic inguinal hernias should be repaired when possible. In some asymptomatic or minimally bothersome hernias, watchful waiting can be an option. There is a multitude of different techniques for hernia repair with different complication and recurrence profiles.

Open Approach

Tissue Repairs

Tissue repairs are repairs where the native tissue is used to close the hernia defect with suture, and no mesh is used. These repairs are used when the operative field is contaminated or in emergency surgery where the viability of the hernia contents is in question. The 3 main primary tissue repairs are the Bassini, Shouldice, and McVay. The Shouldice has the lowest recurrence rate when experienced surgeons perform tissue repairs. McVay is the only technique that can be used in femoral hernia repair. All surgeons should have a good grasp of the technical aspects of these repairs, as a primary repair will likely be the only option in a contaminated case. Prosthetic repairs are preferred over native tissue repair due to lower incidence of recurrence.

Prosthetic Repairs

The prosthetic repairs are tension-free repairs, and thus, these have a lower hernia recurrence rate as compared to tissue repairs. The prosthetic repairs are the Lichtenstein tension-free repair, plug and patch, and Prolene Hernia System (PHS). Lichtenstein repair is the most popular and used most around the world. The Prolene Hernia System repair is the only one of the 3 that places a mesh in the preperitoneal space with an open repair. Mesh repairs are contraindicated in a contaminated field due to the high rate of infection.

Laparoscopic Repairs

Transabdominal Preperitoneal Procedure (TAPP)

The transabdominal preperitoneal procedure TAPP is a technique where a hernia is repaired through an intraperitoneal approach. TAPP can be useful for bilateral hernia repair, large hernia defects, and recurrence after open repair. A large mesh can be placed with this approach covering the direct, indirect and femoral spaces. The disadvantage to this approach is a complication to other intraperitoneal viscera and structures. A patient must be able to tolerate pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic approaches.

Total Extraperitoneal Procedure (TEP)

The laparoscopic extraperitoneal procedure is a technique where the hernia repair is completed without intraperitoneal infiltration. This minimizes risks of injury to intraperitoneal viscera and structures when compared to a TAPP repair. The TEP procedure also avoids intraperitoneal adhesions from prior surgery making the dissection quicker and easier. The disadvantage to the TEP procedure is that the surgeon is constrained to limited space while dissecting. Visualization of the surrounding anatomy is limited as compared to TAPP repair. If the peritoneum is violated during the procedure, then conversion to TAPP may be warranted.

Laparoscopic repairs compared to open repairs have equivalent recurrence rates. The laparoscopic approach has been shown to improve postoperative pain and patients may resume normal activities sooner as compared to open repair. However, laparoscopic repair is associated with higher operative costs, and technical proficiency can be difficult to achieve. Some studies suggest it takes as many as 250 laparoscopic hernia repairs for a surgeon to reach optimal proficiency.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for a groin bulge includes a hernia, lymphadenopathy, lymphoma, metastatic neoplasm, hydrocele, epididymitis, testicular torsion, abscess, hematoma, femoral artery aneurysm, and/or an undescended testicle.

Staging

Groin hernias are categorized into 2 main categories: inguinal and femoral. Inguinal hernias are further subdivided into direct and indirect. An indirect hernia occurs when abdominal contents protrude through the internal inguinal ring and into the inguinal canal. This occurs lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. The hernia contents may extend into the scrotum. A direct inguinal hernia is protrusion of abdominal contents through the transversalis fascia within Hesselbach’s triangle. The borders of Hesselbach’s triangle are the inferior epigastric vessels superolaterally, the rectus sheath medially, and inguinal ligament inferiorly. A femoral hernia is a protrusion into the femoral ring. The borders of the femoral ring are the femoral vein laterally, Cooper’s ligament posteriorly, the iliopubic tract/inguinal ligament anteriorly and lacunar ligament medially.

Classification

There are several classifications for inguinal hernias. Currently, there is no universal classification system for inguinal hernias. One simple and widely used classification is the Nyhus classification which categories hernia defects by size, location, and type.

Nyhus Classification System

Type I

- An indirect hernia; normal size internal ring; typically in infants, children and small adults

Type II

- An indirect hernia; enlarged internal ring without impingement on the floor of the inguinal canal; does not extend to the scrotum

Type IIIA

- A direct hernia; size not taken into account

Type IIIB

- An indirect hernia that has grown enough to infringe upon the posterior inguinal wall; indirect sliding or scrotal hernias are regularly assigned to this category because they are often associated with the extension to direct space. This type also includes pantaloon hernias

TYPE IIIC

- A femoral hernia

Type IV

- A recurrent hernia; modifiers A to D are sometimes added that correspond with direct, indirect, femoral or mixed respectively

Prognosis

Overall, inguinal hernias are associated with a good prognosis. It has generally been accepted that all inguinal hernias should be repaired; although, this idea has recently come into question. Recent articles suggest that watchful waiting is a safe and acceptable option for men in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic cases. Watchful waiting is considered an acceptable treatment option as the risk of incarceration and strangulation in the studies was minimal. It is generally accepted that all hernia patients who are medically cleared for surgery, as well as patients with symptomatic inguinal hernia, should be offered elective surgery. Femoral hernias should always be repaired as they have a high risk of incarceration. The risk of complication is increased in incarcerated, strangulated and recurrent hernias.

Complications

Reports of complications after elective inguinal hernia repair are approximately 10% overall. The most commonly reported complications are similar to those seen in other operations and include seroma, hematoma, urinary retention, and surgical site infection. Two serious complications directly related to an inguinal hernia are hernia recurrence and chronic pain.

Hernia Recurrence

Elective repair of an inguinal hernia has a low rate of recurrence overall. Recurrence with mesh repair is lower compared to recurrence with suture repair with rates of 3% to 5% and 10% to 15% respectively. Recurrence is associated with technical factors like improper mesh size, excessive tension on repair, missed hernias and tissue ischemia. Comorbidities associated with hernia recurrence are smoking, steroid use, diabetes, malnutrition, and chronic cough. As a general rule, re-operations are usually done laparoscopically for previous open repairs and open approach for previous laparoscopic hernia repairs. This facilitates easy exposure and dissection through a fresh plane without scar tissue and decreases injury and complications to cord structures and nerves.

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain following inguinal hernia repair is reported in approximately 10% of cases overall. It remains a challenging problem and has superseded hernia recurrence as the primary complication. In open repairs, identification, and protection of the ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and iliohypogastric nerves are essential in the prevention of nerve entrapment injuries. In laparoscopic repairs, it is essential to avoid using tacks or sutures to secure the mesh inferior to the iliopubic tract beyond the external iliac artery as this can cause injury of the genitofemoral or lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. When a nerve is injured, it should be transected and ligated proximally. Treatment of chronic pain should be conservative, and a multidisciplinary approach is essential. Anti-inflammatory medications should be used as first-line agents. When these are unsuccessful nerve blocks may be implemented. Groin exploration with neurectomy of all three nerves may be necessary and may improve pain when other treatments have failed.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Inguinal hernia repair is usually performed in an ambulatory setting with the patient being discharged the same day of operation. The patient should be able to void independently before discharge. Proper detailed instructions should be given. Narcotics can be given for pain control but should be alternated with NSAIDs or acetaminophen. Patients should be instructed on their pain experience and side effects of narcotic use. A stool softener or cathartic should be used to avoid constipation with narcotic use. Patients are usually able to advance their diet as tolerated to a regular diet on the day of discharge. The patient can usually shower 24 to 48 hours after discharge per surgeon preference. The activity should be limited to lifting no more than 10 pounds (4.5 kg) the first week, 20 pounds (9 kg) the next week, and lifting as needed after that. Vigorous activities should be avoided for 4 to 6 weeks. Return to work is normally 1 to 2 weeks after surgery. However, return to work is dependent on individual work activities and the patient’s pain experience and thus needs to be determined on a case by case basis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of inguinal hernia is best done with an interprofessional team. The majority of patients with an inguinal hernia first present to the nurse practitioner and primary care provider. These clinicians should be able to work up a patient with an inguinal hernia and make the appropriate referral to a surgeon. Unlike the past, the accumulating evidence indicates that asymptomatic patients with small hernias can be observed. Thus, the primary care providers including the nurse should advocate weight loss, a healthy diet and a change in lifestyle to avoid progression of the hernia.

All patients with an inguinal hernia should be referred to a general surgeon because there is always the potential for incarceration or strangulation. Today, there are many surgical techniques available to repair inguinal hernias. While most patients do have a good outcome, complications like nerve injury, bowel injury, recurrence, and wound infections are not uncommon. Prior to surgery, all men older than 50 and have risk factors for cardiac and lung disease should be seen by the anesthesiologist nurse to ensure that they are fit for surgery. Some of these patients may need cardiology and pulmonary clearance.

After surgery, recovery is often prolonged and most patients have moderate to severe pain, depending on how the surgery was performed. The pharmacist should advise the patient on how to manage the pain, discontinuation of smoking, and gradually becoming active after the pain has subsided.

Irrespective of how the surgery is done, a small percentage of patients do develop recurrence.[10] (Level 1). The primary care providers should encourage patients to lose weight to reduce the risk of recurrence.[11][12]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Decker E, Currie A, Baig MK. Prolene hernia system versus Lichtenstein repair for inguinal hernia: a meta-analysis. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2019 Jun:23(3):541-546. doi: 10.1007/s10029-019-01897-w. Epub 2019 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 30771031]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMuschaweck U, Koch A. [Sportsmen's groin : Definition, differential diagnosis and treatment]. Der Radiologe. 2019 Mar:59(3):224-233. doi: 10.1007/s00117-019-0499-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30767027]

Sun L, Shen YM, Chen J. Laparoscopic versus Lichtenstein hernioplasty for inguinal hernias: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Minimally invasive therapy & allied technologies : MITAT : official journal of the Society for Minimally Invasive Therapy. 2020 Feb:29(1):20-27. doi: 10.1080/13645706.2019.1569534. Epub 2019 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 30762458]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLi J,Gong W,Liu Q, Intraoperative adjunctive techniques to reduce seroma formation in laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty: a systematic review. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2019 Feb 8; [PubMed PMID: 30734117]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFernando H, Garcia C, Hossack T, Ahmadi N, Thanigasalam R, Gillatt D, Leslie S, Doeuk N, Smith I, Woo HH. Incidence, Predictive Factors and Preventive Measures for Inguinal Hernia following Robotic and Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy: A Systematic Review. The Journal of urology. 2019 Jun:201(6):1072-1079. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000133. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30730406]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchmitz R, Willeke F, Barr J, Scheidt M, Saelzer H, Darwich I, Zani S, Stephan D. Robotic Inguinal Hernia Repair (TAPP) First Experience with the New Senhance Robotic System. Surgical technology international. 2019 May 15:34():243-249 [PubMed PMID: 30716159]

Tam V, Rogers DE, Al-Abbas A, Borrebach J, Dunn SA, Zureikat AH, Zeh HJ 3rd, Hogg ME. Robotic Inguinal Hernia Repair: A Large Health System's Experience With the First 300 Cases and Review of the Literature. The Journal of surgical research. 2019 Mar:235():98-104. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.09.070. Epub 2018 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 30691857]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePayiziwula J,Zhao PJ,Aierken A,Yao G,Apaer S,Li T,Tuxun T, Laparoscopy Versus Open Incarcerated Inguinal Hernia Repair in Octogenarians: Single-Center Experience With World Review. Surgical laparoscopy, endoscopy [PubMed PMID: 30640818]

Clelland AD, Varsou O. A qualitative literature review exploring the role of the inguinal ligament in the context of inguinal disruption management. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2019 Mar:41(3):265-274. doi: 10.1007/s00276-018-2170-6. Epub 2018 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 30570676]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNedelcu M, Verhaeghe P, Skalli M, Champault G, Barrat C, Sebbag H, Reche F, Passebois L, Beyrne D, Gugenheim J, Berdah S, Bouayed A, Michel Fabre J, Nocca D. Multicenter prospective randomized study comparing the technique of using a bovine pericardium biological prosthesis reinforcement in parietal herniorrhaphy (Tutomesh TUTOGEN) with simple parietal herniorrhaphy, in a potentially contaminated setting. Wound repair and regeneration : official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society. 2016 Mar:24(2):427-33. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12386. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26609642]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVu JV, Gunaseelan V, Dimick JB, Englesbe MJ, Campbell DA Jr, Telem DA. Mechanisms of age and race differences in receiving minimally invasive inguinal hernia repair. Surgical endoscopy. 2019 Dec:33(12):4032-4037. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-06695-0. Epub 2019 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 30767140]

Mellert LT,Cheung ME,Zografakis JG,Dan AG, Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair Using ProGrip Self-Fixating Mesh: Technical Learning Curve and Mid-Term Outcomes. Surgical technology international. 2019 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 30753740]