Introduction

Sebaceous carcinoma is an uncommon and aggressive epithelial malignancy involving the sebaceous gland. While this malignancy is predominant in the head and neck region, it represents a rare malignant skin adnexal tumor typically observed in individuals in their 7th decade of life.[1]

The World Health Organization classifies sebaceous carcinoma into 2 categories: periocular and extraocular.[2] The former accounts for 75% of cases, primarily affects the eyelid, and exhibits a higher metastatic potential. Periocular sebaceous carcinoma also ranks as the 3rd most common eyelid malignancy after basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Notably, extraocular sebaceous carcinoma tumors demonstrate a significant association with visceral malignancies.

Within the spectrum of sebaceous carcinoma, the periocular subtype presents a distinct management challenge due to the increased likelihood of regional metastasis and poorer prognosis, largely stemming from the possibility of orbital invasion. These rare adnexal tumors, commonly misdiagnosed as chalazion, blepharitis, or nevus, are fast-growing and may lead to distant metastasis. Sebaceous carcinoma's association with Muir-Torre syndrome (MTS)—a condition characterized by cutaneous sebaceous tumors, visceral malignancies, and keratoacanthomas due to deoxyribonucleic acid microsatellite instabilities—adds another layer of complexity to its clinical presentation. Experts recommend screening patients with sebaceous carcinoma for MTS, emphasizing the importance of early detection and comprehensive management.[3]

Historically, wide local excision (WLE) was the mainstay of treatment for sebaceous carcinoma. However, recent developments advocate Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) as a more favorable option. MMS ensures clear margins before reconstruction and proves particularly attractive in the treatment of this tumor, allowing for tissue conservation in cosmetically sensitive areas and potentially lowering recurrence rates.[4] Despite the reduced recurrence and metastatic rates, sebaceous carcinoma still has a high mortality and poor prognosis rate. A quicker and more accurate diagnosis can improve patient outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Sebaceous carcinoma development is linked to various factors, including ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure, organ transplants, and immunosuppression with medications like cyclosporine. Additionally, this malignancy is associated with genetic cancer predisposition syndromes, such as MTS-I, which is a distinct variant of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), sometimes referred to as Lynch syndrome.[5] Sebaceous carcinoma is also associated with MTS-II, a MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) variant.[6]

MTS-I is characterized by a germline mutation in mismatch repair (MMR) genes, including mutL homolog1 (MLH1), mutS homolog2 (MSH2), mutS homolog6 (MSH6), postmeiotic segregation increased 2 (PMS2), and the non-MMR gene epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EBCAM), which epigenetically silences the closely linked MSH2 gene. These germline mutations are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. Patients with mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 tend to have a higher risk of malignant tumors than those with MSH6 gene mutations. Notably, 90% of mutations in MTS occur in the MSH2 gene, which is associated with more sebaceous neoplasms than the MLH1 gene.

Approximately 18.8% to 33.3% of patients with sebaceous tumors are diagnosed with HNPCC. Notably, sebaceous skin lesions develop after a visceral malignancy is diagnosed in over half of the cases. In 22% of cases, skin tumor growth precedes visceral neoplasia by up to 25 years. Malignancies commonly associated with HNPCC include gastrointestinal (colorectal), endometrial, and genitourinary types. Research suggests a more aggressive sebaceous carcinoma in patients with MTS than in those without, with a 5-year sebaceous carcinoma-specific survival of 52.5% in patients with MTS compared to 78.2% in individuals without the syndrome. However, this observation is based on a small patient sample.[7]

The subtype MTS-II, a variant of MAP, comprises around 35% of tumors in patients with MTS. This subtype is due to Y179C and G396D mutations in the MUTYH base excision repair gene, leading to an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern.[8] In addition to developing numerous adenomatous polyps and, consequently, colorectal cancer, affected individuals are predisposed to sebaceous adenomas, sebaceous epitheliomas, and sebaceous carcinomas. In contrast to patients with MTS-I, MTS-II cases present later in life.[9]

Epidemiology

In 2020, sebaceous carcinoma demonstrated an estimated annual incidence rate of 1 to 2 cases per million people, positioning it as the 3rd most prevalent eyelid malignancy after BCC and SCC. The peak incidence of this malignancy is observed in individuals between 60 and 79, with a higher incidence in men compared to women; the male-to-female ratio is 1.4:1. Periocular sebaceous carcinoma exhibits distinct epidemiological patterns; in Asia, the neoplasm accounts for 40% to 60% of eyelid tumors, while it represents only 1% of periorbital tumors in resource-rich nations. Additionally, extraocular sebaceous carcinoma comprises 25% of all sebaceous carcinomas, primarily occurring in the head and neck region, especially on the face.[10]

Risk factors for the development of sebaceous carcinoma include male sex, White, Asian, and Indian ethnicities, a history of radiation and UVR exposure, preexisting nevus sebaceous tumors, MTS, and immunosuppression. While MTS is considered a relatively rare disorder, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 500,000 people, underdiagnosis suggests the true prevalence may be higher. MTS is present in 9.2% of patients with HNPCC, with a male-to-female ratio of 3:2 and an HNPCC incidence of 1:440. The 5-year survival rate for patients in England with sebaceous carcinoma was recorded at 78.2%, with a mean survival of 3.04 years following diagnosis. In patients with MTS, the observed lower survival rate may be attributed to the presentation of other cancers associated with HNPCC that remained undiagnosed at the time of sebaceous carcinoma detection.

In one study, approximately 19% of patients developed at least 1 additional recognized HNPCC-associated cancer, with 29% of these cancers occurring after a diagnosis of sebaceous carcinoma. The median time from the diagnosis of sebaceous carcinoma to the development of a subsequent HNPCC-associated cancer was 2.3 years. Certain malignancies, including colorectal, small bowel, upper urinary tract, and salivary gland cancers, demonstrated significantly higher rates following sebaceous carcinoma diagnosis. Sebaceous carcinoma cohorts exhibited high yields of underlying MTS or HNPCC, with estimates ranging from 18.8% to 33.3%.[11]

Pathophysiology

The sebaceous glands exhibit structural and embryological associations with the hair sheath, positioning themselves adjacent to hair follicles, apocrine ducts, and arrector pili muscles. Their concentration is highest over the head and neck region. Notably, sebaceous glands change over time, with older individuals producing less sebum and the sebocytes displaying slower migration and prolonged retention.

Sebaceous carcinoma originates from sebaceous glands and can manifest in any location where these glands are present. The transcription enhancer binding factor LEF1 mutation plays a critical role in skin tumor development, characterized by complete silence in sebaceous carcinomas. At the same time, sebaceomas and sebaceous adenomas may also present mutations related to this factor.

The dysregulation of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), phosphatase and TENsin homolog (PTEN), and nuclear factor κ-B (NFk-B) and the inactivation of p53 have been identified in some sebaceous carcinomas. Additionally, elevated expression levels of tyrosine kinase, particularly HER2, have been linked to sebaceous tumors, prompting investigations into targeted treatment. Aberrations in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway also strongly correlate with abnormal and malignant proliferation within the sebaceous gland.

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is commonly dysregulated in sebaceous carcinoma and may represent a potential therapeutic target.[12][13][14] Aberrant activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway promotes tumor cell proliferation, survival, and resistance to apoptosis, contributing to disease progression and treatment resistance. Targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway components with inhibitors has shown promise in preclinical studies and may offer therapeutic benefits to patients with advanced or refractory sebaceous carcinoma.

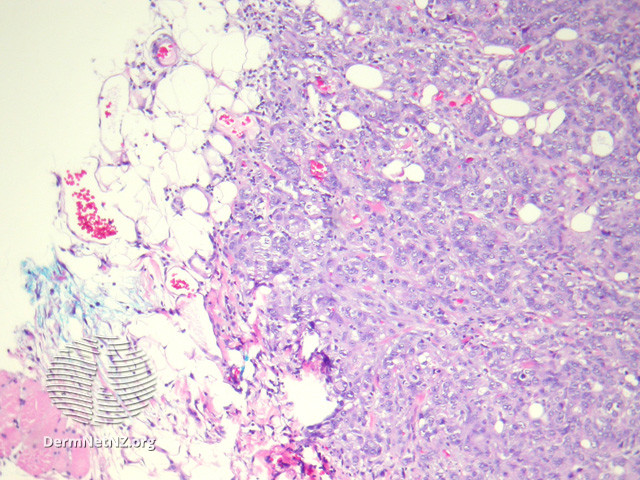

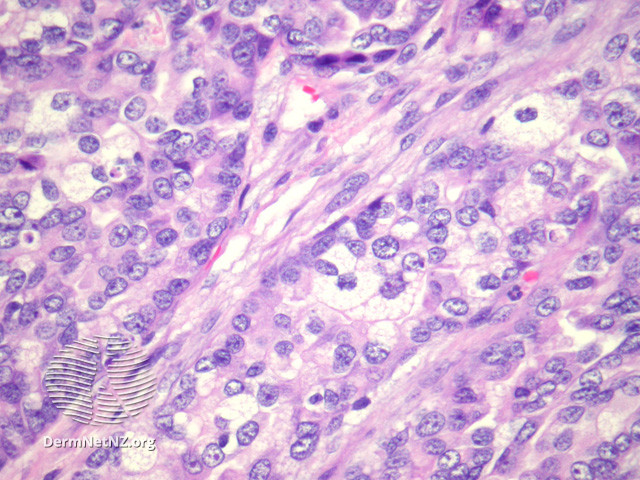

Histopathology

Sebaceous carcinoma histologically exhibits an irregular lobular basaloid tumor with pagetoid spread extending into the epidermis, potentially reaching the dermis and subcutis (see Image. Sebaceous Carcinoma, Low Power).[15] Increased foamy cells with undifferentiated and pleomorphic sebocytes are characteristic (see Image. Sebaceous Carcinoma, High Power).[16] Sebaceous carcinoma exhibits significant histological diversity, with classifications based on differentiation and distinct patterns. Tumors may be well, moderately, or poorly differentiated, with 4 recognized patterns that include lobular, comedocarcinoma, papillary, and mixed. The cells display marked variations in nuclear shape and size, hyperchromatism, a basaloid appearance, and high mitotic activity. Notably, undifferentiated cells exhibit eosinophilic cytoplasm with frothy appearance-inducing lipid granules. Pagetoid tumor growth is common in periocular lesions, while extraocular locations may present with unusual features, such as squamous metaplasia or focal apocrine differentiation.

The World Health Organization proposes 3 levels of grading, ranging from well-demarcated tumors, designated as grade I, to highly invasive growth patterns, designated as grade III. High-grade status is an independent predictor of advanced disease and poor outcomes in sebaceous carcinoma. Staining techniques play a crucial role in diagnosis, with oil red O stain, Sudan IV stains, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and Leu-M1 being helpful. Immunohistochemical markers such as creatine kinase, EMA, cytokeratin 5.2, and anti-breast cancer antigen-225 antibodies are commonly positive, confirming sebaceous differentiation. Positive immunoreactivity for EMA and negative staining for Ber-Ep4 are characteristic of sebaceous tumors and SCCs, distinguishing them from BCCs. Additionally, PRAME (PReferentially expressed Antigen in MElanoma) immunostaining is emerging as a valuable tool for subclassifying sebaceous carcinoma into grades I, II, and III, highlighting the presence or absence of mature sebaceous differentiation. Potential mimickers, including benign sebaceous neoplasms, endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma, spiradenocarcinoma, clear cell hidradenocarcinoma, and poroma, must be recognized. A comprehensive understanding of sebaceous carcinoma's histopathological features and immunohistochemical markers is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

History and Physical

Sebaceous carcinoma initially manifests as a painless, flesh-colored papule (see Image. Sebaceous Carcinoma, Left Nasal Ala). Lesions gradually expand within the surface epithelium and may exhibit a yellow coloration due to lipid accumulation. Alternatively, sebaceous carcinoma can present as a pedunculated lesion, irregular mass, or diffusely thickened skin. Notably, approximately 75% of these cases occur in the periocular region, with the upper eyelid 2 to 3 times more frequently involved than the lower eyelid.

Sebaceous carcinoma manifests as yellow, pink, or red firm nodules of varying sizes in extraocular presentations. Unlike the periocular subtype, the clinical features of extraocular neoplasms are nonspecific. Extraocular sebaceous carcinoma primarily localizes to the head and neck, followed by the trunk, salivary glands, genitalia, breast, ear canal, and oral cavity.

Evaluation

The diagnosis and management of sebaceous carcinoma pose challenges due to the condition's diverse histologic growth patterns and varied clinical presentations, often leading to its misidentification as a common benign entity. This confusion is a key factor contributing to diagnostic delays, inappropriate management, and increased morbidity and mortality. The definitive diagnosis of sebaceous carcinoma is established through incisional or partial-thickness biopsy, with scouting biopsies performed in cases of severe inflammation. In the periocular area, conjunctival map biopsies help determine the extent of the disease.

Cheung et al reported patterns of managing periocular sebaceous carcinoma, noting a consensus on performing mapping biopsies when clinical suspicion arose for pagetoid involvement of the conjunctiva in cases of recurrent disease or when both upper and lower eyelids were involved.[17] Notably, periocular primary site tumor size exceeding 2 cm and regional or distant disease correlates strongly with high-grade tumors compared to truncal and localized involvement.[18] In advanced cases, sebaceous carcinoma may lead to ulceration and distorted vision. If left untreated, metastasis to local lymph nodes and the parotid gland is not infrequent.

Extraocular sites are more commonly associated with syndromic conditions such as MTS. The identification of MTS employs criteria from the Mayo MTS risk score. The scoring system incorporates the following:

- Age younger than 60 years at diagnosis of sebaceous neoplasm: 1 point

- Two or more sebaceous neoplasms, including sebaceoma and sebaceous adenoma: 2 points

- Presence of a personal or family history of an HNPCC-associated neoplasm: 1 point each

The Mayo MTS risk score demonstrates a reported sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 81%. Total scores, ranging from 0 to 5, create the Mayo MTS risk score, with a score of 2 or more having a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 81% for predicting a germline mutation in an HNPCC mismatch repair gene. This scoring system applies to patients with sebaceous adenomas, sebaceous epitheliomas, sebaceomas, and sebaceous carcinomas. HNPCC-related cancers encompass colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, small bowel, urinary tract, and biliary tract cancers.

Treatment / Management

The gold standard technique for sebaceous carcinoma treatment is complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment (CCPDMA), which includes MMS and the Tubingen torte technique. Sebaceous carcinomas may also be treated with WLE.[19] Excision margins of 5 to 6 mm are commonly regarded as standard. However, these margins have been linked to a 5-year mortality rate of 18% and recurrence rates of up to 30% to 37% within 5 years, with regional metastases occurring in 28% of cases. Outcomes are similar regardless of the addition of adjuvant radiotherapy. Frozen section margin control is also recommended, although freezing artifacts may pose challenges.[20]

Since sebaceous carcinoma predominantly occurs on the head or neck in 70% of cases, it necessitates a tissue-preserving surgical approach. MMS for sebaceous carcinoma exhibits significantly lower local recurrence rates (11%) and regional metastases (6%-8%) than WLE. MMS may also gain preference due to shorter healing times and minimal scar formation, increasing patient satisfaction. Despite MMS showing lower recurrence and metastatic rates, retrospective studies underscore the need for standardized protocols and acknowledge potential shortcomings, such as false margins and the requirement for multiple Mohs stages to achieve histological clearance.[21]

Destructive techniques, such as electrodesiccation and curettage, are discouraged due to the propensity for relapse or metastasis. Incomplete removal of the primary tumor poses a significant concern, as do other high-risk factors like comorbidities, advanced age, and the primary site influencing overall survival. Radiation and systemic therapy have become a recommended alternative for nonsurgical candidates, with adjuvant indications for positive margins, incomplete excision, or perineural invasion.

Regional radiotherapy is also preferred over complete node dissection in patients who have positive sentinel lymph node biopsy results, are status post lymphadenectomy, show evidence of nodal metastasis, or require palliative treatment.[22] Systemic therapies for the management of unresectable sebaceous carcinoma include immunotherapies or targeted therapies such as antiandrogens, retinoid receptor ligands, and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Close examination and lymph node imaging, with ultrasound or computed tomography and positron emission tomography-computed tomography for advanced cases, should be performed every 6 months for the first 3 years after treatment.

Management guidelines of sebaceous carcinoma recommend germline testing for MTS or HNPCC for any extraocular sebaceous carcinoma, a Mayo MTS risk score greater than or equal to 2, or age younger than 50 years with a sebaceous carcinoma tumor that has an MMR mutation. These patients must be screened, as sebaceous carcinoma tends to precede visceral cancers in approximately 60% of cases. Endoscopic examinations should start at 25 years of age and be performed annually. Colonoscopies should start at 25 years of age and be performed every 1 to 2 years, or 5 years from the youngest age of colorectal cancer diagnosis in a 1st-degree family member. Annual complete blood cell count and age-appropriate colon cancer screening or surveillance should be ordered. Men should do annual prostate and testicular exams, as indicated. Women should have an annual breast and pelvic examination with endometrial sampling as well as uterine ultrasound, as indicated.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for ocular sebaceous carcinoma encompass a range of conditions, such as chalazion, cysts, blepharitis, and other inflammatory ocular disorders, including blepharoconjunctivitis or keratoconjunctivitis. Similarly, for extraocular sebaceous carcinoma, the spectrum of potential differentials widens to include pyogenic granuloma, molluscum contagiosum, BCC, SCC, and adnexal neoplasms like sebaceous adenoma. Histologically, distinguishing sebaceous hyperplasia, nevus sebaceous (of Jadassohn), sebaceous adenoma, sebaceoma, and BCC with sebaceous differentiation from sebaceous carcinoma can be challenging. Additionally, the often nonspecific appearance of extraocular sebaceous carcinomas complicates clinical diagnosis, leading many cases to be initially mistaken for BCC until confirmed by histopathological examination.

Radiation Oncology

The role of radiation therapy in the management of periocular sebaceous carcinomas has been a subject of ongoing investigation. Adjuvant radiotherapy emerges as a crucial consideration, particularly when the lacrimal system or the orbit is involved, offering a viable alternative to exenteration. Additionally, adjuvant radiotherapy may be considered in cases where perineural invasion is evident or excisional margins are positive. Nevertheless, uncertainties persist regarding the overall increase in survival with lymph node radiation therapy, underscoring the need for further investigation in this domain.

Notably, radiation treatment as monotherapy is currently not recommended and should be reserved for inoperable cases. However, studies advocate for its primary application, showcasing promising outcomes such as complete or near-complete response rates and favorable prognosis for eyelid carcinomas. Importantly, the success of primary radiotherapy correlates with dosing, with 5-year progression-free survival rates ranging from 57% to 93%.[23] Sessions delivering doses over 55 Gy have shown promise in enhancing disease control, albeit in a limited number of cases.

Conversely, information concerning radiation therapy for extraocular carcinomas remains limited, primarily reserved for nonsurgical candidates, metastatic cases, and residual tumors. Notably, definitive treatment with radiation therapy for sebaceous carcinoma is recommended for nonsurgical candidates, with dosages ranging from 50 to 70 Gy in 2-Gy fractions with a 2-cm margin for extraocular tumors and variable margin for periocular lesions, depending on specific location. Adjuvant radiotherapy enhances overall survival rates in cases where surgical margins are positive or nodal metastases are evident. Whether as a complementary measure following complete excision or as a standalone treatment for incomplete excised tumors or perineural invasion, radiation therapy demonstrates notable efficacy, with 5-year overall survival rates ranging from 57% to 80%.

Moreover, adjuvant radiation therapy to the regional nodal basin offers a viable alternative to completed lymph node dissection in patients with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy and post therapeutic lymphadenectomy for evident nodal metastasis. Palliative radiotherapy is a valuable tool in managing advanced disease and cutaneous metastases, offering symptom relief and enhancing the quality of life for affected individuals.[22]

Staging

Staging guidelines for periocular sebaceous carcinoma are outlined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual 8th Edition (AJCC8):

- T1: Tumor size is less than or equal to 10 mm in greatest dimension

- T1a: No invasion of the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T1b: Invasion of either the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T1c: Involves full thickness of the eyelid [24]

- T2: Tumor size is more than 10 mm but less than or equal to 20 mm

- T2a: No invasion of the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T2b: Invasion of either the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T2c: Involves full thickness of the eyelid

- T3: Tumor size is greater than 20 mm but less than or equal to 30 mm

- T3a: No involvement of the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T3b: Involvement of either the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T3c: Involves full thickness of the eyelid

- T4: Any eyelid tumor that invades adjacent ocular, orbital, or facial structures

- T4a: Invades ocular or intraorbital structures

- T4b: Invades the body walls of the orbit, extends to the paranasal sinuses, or invades the lacrimal sac, nasolacrimal duct, brain

A tumor size of 1 to 2 cm correlates with a worse overall prognosis. A sentinel lymph node biopsy may be considered for Stage T2c periocular sebaceous carcinoma or higher-grade disease.[25]

Meanwhile, consensus or staging guidelines for extraocular sebaceous carcinoma have yet to be established. Thus, this malignancy is staged like cutaneous SCC of the head and neck based on the AJCC8.[26]

- Stage I

- Tumor size smaller than or equal to 2 cm in greatest dimension (T1)

- No regional lymph node metastasis (N0)

- No distant metastasis (M0)

- Stage II

- Tumor size greater than 2 cm but less than 4 cm (T2)

- No regional lymph node metastasis (N0)

- No distant metastasis (M0)

- Stage III

- Tumor size greater than 4 cm (T3) or one of the following is an associated feature:

- Minor bone erosion

- Perineural invasion

- Deep invasion beyond the subcutaneous fat

- No regional lymph node metastasis (N0)

- No distant metastasis (M0)

- Also includes T1 to T3 with metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node that is 3 cm or greater, no extranodal extension (N1), and no distant metastasis (M0) [27]

- Stage IV

- A tumor can be classified as s

- tage IV without any lymph node involvement or distant metastasis if it demonstrates gross cortical bone involvement, bone marrow invasion, skull base invasion, or skull base foramen involvement (T4).

- Nodal events may also lead to a Stage IV classification without distant metastasis.

- Any distant metastasis (M1) results in a stage IV classification.

Prognosis

In recent years, advancements in disease awareness and the application of advanced excision procedures, such as MMS, have led to a significant improvement in survival rates among individuals diagnosed with sebaceous carcinoma. However, despite these advancements, sebaceous carcinoma remains a formidable challenge due to its high rates of recurrence and metastasis. Notably, mortality rates for sebaceous carcinoma vary widely, ranging from 9% to 50%, reflecting the heterogeneity of the disease and its management outcomes. Periocular sebaceous carcinoma exhibits recurrence rates ranging from 11% to 30%, with distant metastasis occurring in 3% to 25% of cases.

Initially perceived as less aggressive, extraocular sebaceous carcinoma has garnered more attention due to emerging evidence suggesting comparable aggressiveness to its ocular counterpart. Results from a study examining 91 cases of extraocular sebaceous carcinoma revealed a recurrence rate of 29%, with 21% progressing to metastasis. These findings challenge previous assumptions and underscore the need for comprehensive management strategies, irrespective of tumor location.

Moreover, the impact of MTS association on sebaceous carcinoma prognosis has been subject to debate. While earlier studies suggested worse outcomes in patients with MTS, recent research by Maloney et al indicates a trend toward improved sebaceous carcinoma-specific survival in this cohort. Notably, this trend aligns with observations of MMR-deficient visceral tumors in MTS, which tend to exhibit less aggressiveness and lower-grade characteristics. Maloney et al also note that when not associated with MTS, trunk and extremity tumors are associated with worse overall survival and overall disease-specific survival compared to periocular tumors, possibly due to their larger size.

Another consideration affecting prognosis is disease state. Localized disease carries a more favorable prognosis, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 78%. However, metastatic disease significantly diminishes survival rate, with the 5-year overall survival rate reduced to 50%. This trend highlights the complexity of prognostic assessments and the need for nuanced considerations in treatment planning. Sebaceous carcinoma's propensity for local recurrence and regional and distant metastases underscores the importance of vigilant surveillance and interprofessional management approaches. With a high risk of recurrence and metastasis, meticulous follow-up and comprehensive treatment strategies are imperative.

Complications

Tumors may continue to grow, leading to localized tissue destruction and distant metastasis. Postoperative complications include but are not limited to tumor recurrence, scarring, infection, bleeding, and dyspigmentation. Regarding tumors involving the eyelid, ectropion posttumor resection is always a possibility. Because the tumor is often located in the periocular region, damage to the temporal branch of the facial nerve during procedures around the lateral eyebrow may lead to frontalis muscle denervation. Damage to local blood vessels, like the superficial temporal artery in the temple, is also possible and should be monitored in patients with active bleeding after MMS.

Consultations

Consultations may involve a dermatologist, Mohs micrographic surgeon, oculoplastic surgeon, general surgeon, and radiation oncologist, depending on the tumor's size and location.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is crucial in preventing the onset and progression of sebaceous carcinoma. Concerned individuals should be advised to discuss with their healthcare provider any persistent papule or nodule that continues to grow, bleeds, changes color, or feels tender. Connecting patients with the appropriate subspecialty can facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment, reducing the risk of potential metastasis.

Regular skin examinations provide the most effective preventive method for prompt diagnosis and intervention. For patients with predisposing factors such as MTS, prior radiation therapy, or advanced age, encouraging self-monitoring for suspicious lesions and seeking timely medical evaluation can facilitate early detection. Furthermore, emphasizing the importance of sun protection measures—such as applying sunscreen and avoiding excessive sun exposure—can help reduce the incidence of sebaceous carcinoma, especially in susceptible individuals.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patient-centered care for individuals with sebaceous carcinoma necessitates an interprofessional approach involving primary care clinicians, dermatologists, ophthalmologists, oculoplastic surgeons, and radiation oncologists, among other essential healthcare experts. Primary care clinicians must know the signs and symptoms of potential cutaneous malignancies to direct patients to the appropriate specialist. Recognizing signs of malignant cutaneous findings, such as increasing lesion size, arborizing vessels, ulceration or bleeding, and atypical locations, guides patients to the appropriate specialist.

Dermatologists and oculoplastics specialists should demonstrate proficiency in correct biopsy techniques, offering their pathologists concise and precise differential diagnoses for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Depending on the tumor's size and location, general surgery may be necessary to assist in resection and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Additionally, radiation oncologists may be consulted depending on tumor depth and surgical candidacy.

Establishing individualized care plans for each patient is crucial due to the tumor's various morphological presentations and stages. These plans should consider surgical candidacy, age, and risk factors such as MTS, previous radiation therapy, immunosuppression, and prior nevus sebaceous diagnosis. Considering the patient's autonomy and their preferences is also imperative.

Effective interpersonal communication between patients and all providers is vital to achieving optimal outcomes. Sharing the latest information about the patient and addressing any concerns contributes to this process. Additionally, effective communication helps prevent failures in continuity of care, such as lack of follow-up, delays in specialist consultation, errors in medication prescribing, and risks to patient safety.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Dokic Y, Nguyen QL, Orengo I. Mohs micrographic surgery: a treatment method for many non-melanocytic skin cancers. Dermatology online journal. 2020 Apr 15:26(4):. pii: 13030/qt8zr4f9n4. Epub 2020 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 32621679]

Eisen DB, Michael DJ. Sebaceous lesions and their associated syndromes: part I. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2009 Oct:61(4):549-60; quiz 561-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.04.058. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19751879]

Buffo TH, Stelini RF, Serrano JYM, Pontes LT, Magalhães RF, de Moraes AM. Mohs micrographic surgery in rare cutaneous tumors: a retrospective study at a Brazilian tertiary university hospital. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2023 Jan-Feb:98(1):36-46. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2022.01.009. Epub 2022 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 36369200]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMeer E, Nguyen B, Luna GL, Kim D, Bautista S, McGeehan B, Giordano C, Etzkorn J, Miller C, Briceño CA. Sebaceous Carcinoma of the Face Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2022 Nov 1:48(11):1148-1154. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003603. Epub 2022 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 36194726]

Simic D, Dummer R, Freiberger SN, Ramelyte E, Barysch MJ. Clinical and Molecular Features of Skin Malignancies in Muir-Torre Syndrome. Genes. 2021 May 20:12(5):. doi: 10.3390/genes12050781. Epub 2021 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 34065301]

John AM, Schwartz RA. Muir-Torre syndrome (MTS): An update and approach to diagnosis and management. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016 Mar:74(3):558-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.074. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26892655]

Maloney NJ, Zacher NC, Hirotsu KE, Rajan N, Aasi SZ, Kibbi N. Comparison of clinicopathologic features, survival, and demographics in sebaceous carcinoma patients with and without Muir-Torre syndrome. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2023 Aug:89(2):269-273. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.032. Epub 2023 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 37003478]

Shah RR, Allman P, Schwartz RA. Muir-Torre Syndrome: A Cutaneous Finding Amidst Broader Malignancies. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2023 May:24(3):375-380. doi: 10.1007/s40257-023-00757-9. Epub 2023 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 36695997]

Guarrera J, Prezzano JC, Mannava KA. Sebaceomas in a Muir-Torre-like Phenotype in a Patient with MUTYH-Associated Polyposis. Dermatopathology (Basel, Switzerland). 2024 Mar 4:11(1):124-128. doi: 10.3390/dermatopathology11010011. Epub 2024 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 38534264]

Papadimitriou I, Vakirlis E, Sotiriou E, Bakirtzi K, Lallas A, Ioannides D. Sebaceous Neoplasms. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2023 May 9:13(10):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13101676. Epub 2023 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 37238164]

Cook S, Pethick J, Kibbi N, Hollestein L, Lavelle K, de Vere Hunt I, Turnbull C, Rous B, Husain A, Burn J, Lüchtenborg M, Santaniello F, McRonald F, Hardy S, Linos E, Venables Z, Rajan N. Sebaceous carcinoma epidemiology, associated malignancies and Lynch/Muir-Torre syndrome screening in England from 2008 to 2018. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2023 Dec:89(6):1129-1135. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.046. Epub 2023 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 37031776]

Kwon MJ, Nam ES, Cho SJ, Park HR, Min SK, Seo J, Choe JY. Mutation analysis of CTNNB1 gene and the ras pathway genes KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA in eyelid sebaceous carcinomas. Pathology, research and practice. 2017 Jun:213(6):654-658. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.02.015. Epub 2017 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 28551389]

Tetzlaff MT, Singh RR, Seviour EG, Curry JL, Hudgens CW, Bell D, Wimmer DA, Ning J, Czerniak BA, Zhang L, Davies MA, Prieto VG, Broaddus RR, Ram P, Luthra R, Esmaeli B. Next-generation sequencing identifies high frequency of mutations in potentially clinically actionable genes in sebaceous carcinoma. The Journal of pathology. 2016 Sep:240(1):84-95. doi: 10.1002/path.4759. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27287813]

Medhus E, Siegel M, Boscia J. A Unique Presentation of Birt-Hogg-Dube Syndrome. Cureus. 2021 Aug:13(8):e17227. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17227. Epub 2021 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 34540454]

Yunoki T, Miyakoshi A, Hayashi A. Clinicopathologic Features of Eyelid Sebaceous Gland Carcinoma Requiring Immunohistochemical Diagnosis. Ocular oncology and pathology. 2024 Sep:10(3):131-138. doi: 10.1159/000538537. Epub 2024 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 39224525]

Lee SC, Peterson C, Wang K, Alaali L, Eshleman J, Mahoney NR, Li E, Eberhart CG, Campbell AA. Establishment and Characterization of Three Human Ocular Adnexal Sebaceous Carcinoma Cell Lines. International journal of molecular sciences. 2024 Sep 23:25(18):. doi: 10.3390/ijms251810183. Epub 2024 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 39337668]

Cheung JJC, Esmaeli B, Lam SC, Kwok T, Yuen HKL. The practice patterns in the management of sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid in the Asia Pacific region. Eye (London, England). 2019 Sep:33(9):1433-1442. doi: 10.1038/s41433-019-0432-0. Epub 2019 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 30952958]

Maloney NJ, Aasi SZ, Hirotsu KE, Zaba LC, Kibbi N. Positive surgical margins in sebaceous carcinoma: Risk factors and prognostic impact. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2023 Jul:89(1):184-185. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.01.049. Epub 2023 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 36907557]

Brady KL, Hurst EA. Sebaceous Carcinoma Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2017 Feb:43(2):281-286. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000943. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28165350]

Elias ML, Skula SR, Behbahani S, Lambert WC, Schwartz RA. Localized sebaceous carcinoma treatment: Wide local excision verses Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatologic therapy. 2020 Nov:33(6):e13991. doi: 10.1111/dth.13991. Epub 2020 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 32645237]

Su C, Nguyen KA, Bai HX, Christensen SR, Cao Y, Tao Y, Karakousis G, Zhang PJ, Zhang G, Xiao R. Comparison of Mohs Surgery and Surgical Excision in the Treatment of Localized Sebaceous Carcinoma. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2019 Sep:45(9):1125-1135. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001780. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30829780]

Wilmas KM, Garner WB, Ballo MT, McGovern SL, MacFarlane DF. The role of radiation therapy in the management of cutaneous malignancies. Part II: When is radiation therapy indicated? Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021 Sep:85(3):551-562. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.057. Epub 2021 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 34116100]

Hata M, Koike I, Maegawa J, Kaneko A, Odagiri K, Kasuya T, Minagawa Y, Kaizu H, Mukai Y, Inoue T. Radiation therapy for primary carcinoma of the eyelid: tumor control and visual function. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie : Organ der Deutschen Rontgengesellschaft ... [et al]. 2012 Dec:188(12):1102-7. doi: 10.1007/s00066-012-0145-9. Epub 2012 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 23104519]

Ding S, Sagiv O, Guo Y, Kandl TJ, Thakar SD, Esmaeli B. Change in Eyelid Carcinoma T Category With Use of the 8th Versus 7th Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer: Cancer Staging Manual. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2019 Jan/Feb:35(1):38-41. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001133. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29877957]

Xu S, Sagiv O, Rubin ML, Sa HS, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, Ning J, Esmaeli B. Validation Study of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Eighth Edition, Staging System for Eyelid and Periocular Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA ophthalmology. 2019 May 1:137(5):537-542. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0238. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30869769]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRuiz ES, Karia PS, Besaw R, Schmults CD. Performance of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition vs the Brigham and Women's Hospital Tumor Classification System for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA dermatology. 2019 Jul 1:155(7):819-825. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0032. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30969315]

Ebrahimi A, Luk PP, Low H, McDowell L, Magarey MJR, Smith PN, Perriman DM, Veness M, Gupta R, Clark JR. A critical analysis of the 8th edition TNM staging for head and neck cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with lymph node metastases and comparison to N1S3 stage and ITEM risk score: A multicenter study. Journal of surgical oncology. 2021 Jun:123(7):1531-1539. doi: 10.1002/jso.26410. Epub 2021 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 33721339]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence