Introduction

Many physicians, especially those working in acute care settings with pediatric patients, frequently encounter foreign bodies in the external auditory canal (EAC).[1] The occurrence of this issue can vary based on the physician's specialty and practice location. The techniques used for removal depend on the specific clinical situation, as each patient is unique. In some cases, patients with ear foreign bodies may require sedation for safe removal and should be evaluated for potential ear trauma or infection. Referring these patients to an otolaryngologist is recommended.

The EAC is the most common location to encounter a foreign body, particularly in children, accounting for 44% of cases, with nasal, pharyngeal, esophageal, and laryngobronchial locations representing 25%, 23%, 5%, and 2% of cases, respectively.[2][3] Pharyngeal foreign bodies are most prevalent in adults, making up 17% of cases.[4]

Foreign bodies typically retrieved include beads (most common), paper or tissue paper, and popcorn kernels, which account for over half of the cases in one study.[5][6] A slight male predominance may be observed, but not all authors agree.[7] Certain types of foreign bodies, such as button batteries, require emergent removal because of the potential release of toxic chemicals. However, extraction from the EAC is not emergent for most inorganic objects. Prolonged retention of foreign bodies and significant edema of the EAC may render foreign body removal more challenging and painful.

This topic aims to help physicians understand the methods for identifying and managing foreign bodies in the EAC and the potential pitfalls and complications involved. Successful ear foreign body recovery depends on the following:

- Type of material

- Characteristics of the lodged object, ie, whether soft or hard, graspable (ie, spherical or with edges), prone to disintegration (such as an insect's body), alive or dead (if animate), and caustic or corrosive

- Location of the foreign body

- Equipment available, including lighting

- Physician training and dexterity

- Patient cooperation

The first attempt to remove a foreign object from the ear is typically the most effective. Physicians should remain alert to the possibility of multiple foreign bodies, especially in young children. Otolaryngologists have significantly higher success rates in performing foreign body removal compared to other healthcare providers, with success rates of 92.9% and 64.1%, respectively.[8]

Patients often require treatment with antibiotic and steroid ear drops, especially if they have lacerations or trauma to the EAC. Perforated tympanic membrane or hearing loss warrants referral for pure-tone audiometry and evaluation by an otolaryngologist.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The EAC is a funnel that transfers sound waves into the ear and is essential for hearing. The middle ear, which includes the tympanic membrane and the ossicles, helps bridge the impedance mismatch between air and the fluid-filled cochlea.

The EAC and the outer layer of the tympanic membrane develop from the 1st branchial cleft. The medial 2/3 of the EAC consists of bony tissue covered with stratified squamous epithelial skin, while the outer 1/3 comprises cartilage. The skin lining the cartilaginous portion of the EAC contains hairs and modified sweat glands that secrete cerumen.

The EAC is primarily innervated by cranial nerves V3 (mandibular branch of the trigeminal) and X (vagus), with a small branch known as the Arnold nerve playing a key role. This nerve can trigger coughing or gagging in some patients during procedures involving the EAC. Cranial nerves VII (facial) and IX (glossopharyngeal) also contribute to the EAC's innervation but to a lesser extent. Lesions at the skull base that affect the facial nerve, such as acoustic neuroma, may lead to hypesthesia (numbness) in parts of the EAC, a phenomenon known as the Hitzelberger sign.[9]

The EAC is nearly straight in young children and reaches approximately 2.5 cm in length around age 9, which is near the adult length. The EAC takes on a gentle sigmoid shape in adults: the cartilaginous portion angles posteriorly and superiorly, while the bony portion courses anteroinferiorly. This curvature pulls the helix posteriorly and superiorly straightens the EAC, which improves the visibility of the tympanic membrane in adults. Defects in the cartilaginous canal are known as the fissures of Santorini, which are susceptible to infection or malignancy.[10]

An essential consideration for managing foreign bodies in the ear is that the EAC has 2 natural narrowings. The narrowest part of the EAC occurs at the junction of the bony and cartilaginous sections, known as the isthmus, which plays an important factor in removing ear foreign bodies and the feasibility and ease of middle ear surgery.[11] The 2nd narrowing is lateral to the tympanic annulus, the fibrocartilaginous structure encircling the pars tensa.[12]

An anatomical feature of the EAC is a rare, potential blind spot in the tympanic sulcus caused by the oblique slope of the tympanic membrane as it approaches the bulge of the temporomandibular joint. This area is known as the Fissures of Huschke (or foramen tympanicum) and represents a potential developmental defect in the anteroinferior aspect of the bony EAC.[13] This anatomical variation is clinically important when evaluating patients with transient otorrhea, especially when no evidence of an ear foreign body or ear disease is found.

The EAC serves as a sound resonator. The length of this structure primarily determines the resonant frequency, while its curvature has little impact on sound perception. However, physical obstruction of the EAC by cerumen, fluid, or foreign objects can disrupt hearing and impair sound localization.

Indications

Ear foreign bodies may present with symptoms that patients may or may not describe in detail, such as ear pain, drainage, tinnitus, dizziness, or hearing loss. Prompt removal is necessary with a strong history or clinical suspicion of a foreign body, especially when the object can be clearly seen in the EAC. The initial removal attempt should be conducted with the best possible equipment and lighting, ensuring the patient's cooperation or the safe ability to sedate or restrain the patient if needed.[14] In many situations, a low threshold for otolaryngology consultation is advisable to maximize success with minimal complications.

Contraindications

Otolaryngologists have no specific contraindications to removing foreign bodies from the ear, though limitations may arise based on the preferred setting, available equipment, and the need for sedation. Removing foreign bodies from the ear and evaluating any resulting damage are essential for appropriate treatment.

Meanwhile, non-otolaryngologists have relative contraindications that include the following:

- The foreign body is ungraspable, tightly wedged, or adjacent to the tympanic membrane.

- The foreign body is sharp.

- Previous removal attempts were unsuccessful.[15]

- The patient is uncooperative.

- Equipment or lighting is insufficient for safe removal.

- The foreign body is composed of a spongy material that may swell when hydrated, making irrigation contraindicated.

- The tympanic membrane is perforated.

- Ear canal trauma is evident.

- Excessive bleeding occurs.

- Pus or abnormal drainage is observed.

- The foreign body is made of organic material.

- The foreign object warranting removal is a battery.

- A tumor or mass, such as cholesteatoma, is suspected.

Patients with these conditions should be referred to an otolaryngologist and treated with more appropriate equipment.

Equipment

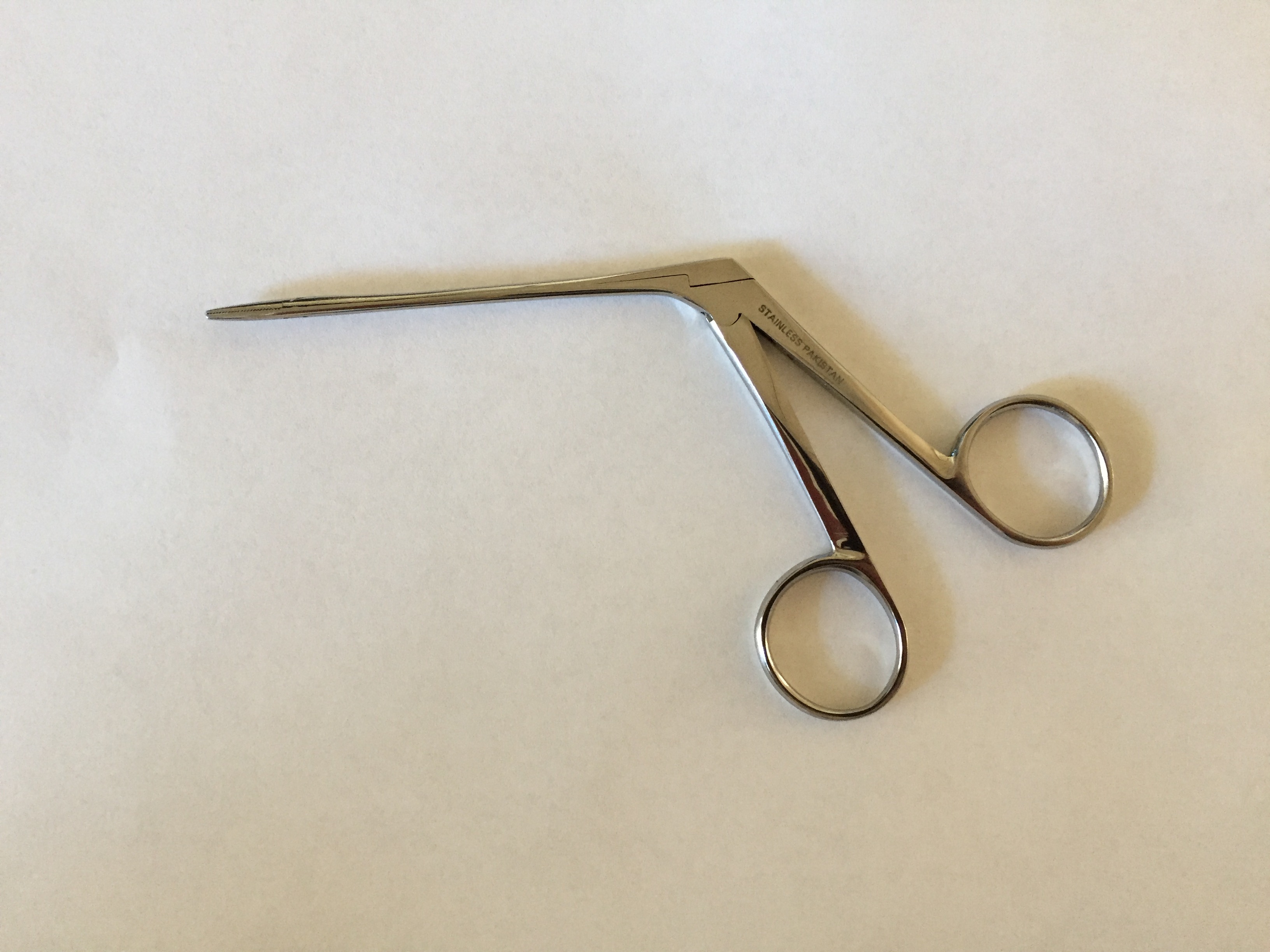

Various methods exist for removing foreign bodies from the EAC. The type, shape, and location of the object, as well as the patient's level of cooperation, determine which equipment is most appropriate to use. Common instruments frequently employed include an otoscope with a removable lens, nasal speculum, alligator forceps, cup forceps, right-angle hooks, Schuknecht foreign body suction tips, curved Rosen picks, and balloon catheters, such as Fogarty catheters (see Image. Alligator Forceps). Binocular microscopy significantly enhances the use of precise and sharper instruments and is the preferred method for otolaryngologists.

Irrigation is a common option. This step may be performed by attaching an angiocatheter to a 20- to 30-mL syringe. Alternatively, a butterfly catheter can be modified by cutting off the needle and then attaching the remaining tubing to the syringe, which can also be effective. Great caution must be exercised with blind irrigation, as tympanic membrane perforation may be undetected initially. Some experts recommend against irrigating the EAC unless the tympanic membrane is completely visualized and its integrity is confirmed.

Suction is also a viable and often used technique, typically performed using a Frazier tip under binocular microscopy. The combination of surgical loupes with a minimum magnification of 2.5x and a headlight is sometimes a sufficient substitute. Magnets may be effective for metallic foreign objects.

Lastly, cyanoacrylate (superglue) or tissue glue may be used to extract ear foreign bodies. The method entails applying the glue to the blunt end of a cotton-tipped applicator and then placing it against the foreign body. Upon adhesion, the applicator and the foreign object may be removed from the EAC together.[16] This technique requires clinical skill, good visualization, and optimal patient cooperation.

If otolaryngology is consulted for a difficult foreign body removal, the management decision may depend on whether the patient requires sedation. These procedures are usually conducted in an operating room with optimal equipment, including otomicroscopy.

Personnel

Clinicians can independently remove the foreign body from the EAC in cooperative patients. However, depending on the patient's level of cooperation, one or more assistants may be needed to help keep the patient still and correctly positioned during the procedure. This type of support is particularly common when treating pediatric patients.[17]

Local anesthesia is invasive and not used because of the complexity of the ear canal innervation. The personnel may include an otolaryngologist, anesthesiologist, nurses, and operating room staff if sedation is necessary. If a foreign body causes ear trauma, a referral to an audiologist and, possibly, a speech therapist may be needed.

Preparation

A thorough head and neck examination, including both ears and nares, must be performed to ensure that all foreign bodies are identified. Clinical evaluation should consider the possibility that an underlying illness may have prompted the patient to insert a foreign object into the ear to relieve discomfort, such as pain or pruritus.[18] A foreign body is unlikely to be present if the patient experiences throat pain that may be referred to the ear.

Examination of the EAC should include the following:

- Identification of the foreign body

- Exclusion of preexisting or iatrogenic tympanic membrane perforations and ear canal abrasions

- Hearing assessment using tuning fork tests or, if available, audiometry

Preparation should include the following:

- Assessment of the type and characteristics of the foreign body

- Patient cooperation

- Patient positioning, whether sitting or lying down. In pediatrics, consider having the patient sit on the parent's lap, with the parent holding the child's head to the side with one hand.

Considerations during the final assessment should include whether otolaryngology should be consulted and if general anesthesia is needed.[19][20]

Technique or Treatment

Before starting the procedure, the physician should decide how many attempts will be made, typically limited to 1 or 2. If more than 1 attempt is planned, the physician should determine which technique will be used for the subsequent attempt. Further attempts should be discontinued if the procedure remains unsuccessful after 1 or 2 tries, and the patient should be referred to an otolaryngologist. The opposite ear and nose must be checked for any foreign bodies, especially in pediatrics. A 2020 study found that 75% of foreign bodies in the EAC may be removed in outpatient settings or emergency departments, while 23% required removal in an operating room under general anesthesia.[21]

Specific Techniques

Various techniques are used for the removal of foreign bodies from the ear, each suited to different types of objects and patient needs. These methods include manual instrumentation, irrigation, suction, cyanoacrylate application, and arthropod removal, each requiring careful consideration of the patient's comfort and safety.

Manual instrumentation

Forceps, curettes, and angle hooks may be employed to manually extract foreign objects from the EAC, typically in conjunction with the operating head of an otoscope. However, these instruments may also be utilized with the diagnostic head. Binocular microscopy is the preferred option, although it may not be available in all settings. Otologic endoscopes may also be very helpful when used by trained professionals.

To visualize the object in the EAC, the pinna—the outer part of the ear—should be pulled back. If forceps are used, the foreign body should be grasped carefully and removed. Both curettes and right-angle hooks should be gently maneuvered behind the foreign object. Once positioned, the tool should be rotated so that the end is behind the object, allowing it to be scooped out effectively. In the case of a button battery or another metallic object, the use of a telescoping rod with a magnet tip—similar to the tools used by mechanics to retrieve dropped screws—can facilitate the removal of the foreign object from the EAC.[22]

Contact with the skin of the EAC must be minimized when using instruments, especially near the tympanic membrane, as this skin is highly sensitive, like the tympanic membrane itself. Utilizing an otologic speculum enhances visibility and lighting. The speculum is typically held with the nondominant hand while the dominant hand operates the primary instrument.

Irrigation

This procedure may be performed using either an angiocatheter or a piece of tubing from a butterfly catheter. First, water should be warmed to body temperature. Then, the pinna should be gently retracted, and warm water should be squirted upward into the EAC, directing it behind the foreign body. This step should help wash the object out of the canal. Water that is too hot or too cold can potentially cause nystagmus, vertigo, nausea, and vomiting due to vestibular stimulation.

Suction

The procedure should be carried out using a suction-tipped catheter equipped with a thumb-controlled release valve, such as a Frazier or Schuknecht foreign body suction tip. Under direct visualization, the suction tip should be pressed against the foreign body. The thumb hole should be occluded to create suction, and the object should be carefully removed, ensuring that suction is maintained until the foreign body is completely extracted from the EAC.

Cyanoacrylate application

A small amount of cyanoacrylate or skin glue is applied to the cotton end of a cotton-tipped applicator. A bit of cotton should be removed to reduce the tip size, which will enhance visibility before the adhesive is applied and the applicator is inserted into the EAC. Once the glue becomes tacky, the applicator should be carefully inserted into the EAC, with the sticky end placed against the foreign body while ensuring clear visualization. The applicator should be held in place until the glue dries. Once the object is firmly attached to the applicator, both the object and the applicator should be removed together. The skin of the ear canal should be avoided while inserting the cotton-tipped applicator to avoid glue adhering to the ear canal instead of the foreign body, resulting in further injury and swelling.

Arthropod removal

The first step is to kill the arthropod, commonly a cockroach or a tick. This action helps the patient feel more comfortable and facilitates the removal of the animal. Research shows that mineral oil is the most effective agent for this purpose, followed by lidocaine, as both substances may be instilled into the EAC.[23] Once the arthropod is neutralized, it can be removed using any of the methods mentioned above. In practice, lidocaine is advantageous because it anesthetizes the EAC, allowing the patient to remain comfortable even if the animal struggles and scratches the sensitive skin.

Complications

The most common complications arising from foreign bodies lodging in the EAC and the subsequent removal attempts include skin excoriations and lacerations. Other potential problems include bleeding, infection, retained foreign body particles, tympanic membrane perforation, and traumatic ossicular dislocations, which are rare with foreign body removal.[24][25]

Both preremoval and postremoval examination findings must be documented, ensuring any preexisting injuries are noted. The EAC's skin heals quickly if kept clean and dry. Antibiotic and steroid eardrops must be considered if lacerations or bleeding are noted in the EAC. In most cases of successful foreign body removal from the ear, prophylactic antibiotics and steroid eardrops, as well as routine follow-up with an otolaryngologist, are typically unnecessary.[26]

The patient should be referred to an otolaryngologist if a clinician cannot remove foreign bodies from the EAC or feels uncomfortable performing the procedure. An otolaryngology referral is also warranted when patients experience delayed pain, redness, fever, and ear drainage. Not all complications are immediately apparent after foreign body removal.

Clinical Significance

Physicians involved in acute patient care will likely encounter patients with foreign bodies in the EAC at some point during their careers. Therefore, acknowledging the limitations of both clinician expertise and available equipment is essential. The type and location of the object within the EAC, as well as the patient's ability to cooperate, are crucial factors in deciding whether a removal attempt should be made. If the initial assessment suggests that removal is not feasible, the patient must be referred to a specialist or a facility where sedation may be provided. Generally, any complications that arise tend to be minor and can be easily managed.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of foreign bodies in the ear requires a collaborative healthcare team focused on delivering patient-centered care, improving outcomes, ensuring safety, and optimizing performance. This team includes physicians, physician assistants, nurses, nurse practitioners, urgent care and emergency room staff, operating room personnel, audiologists, and speech therapists. Each professional plays a vital role in this cooperative approach.

Healthcare providers must have the necessary clinical skills and expertise to diagnose, evaluate, and treat this condition effectively. The required skills include proficiency in patient positioning, the use of proper equipment, and the ability to recognize potential complications. A strategic approach that incorporates evidence-based guidelines and individualized care plans tailored to each patient’s unique situation is essential.

Effective communication among team members is crucial. Physicians and nurses must swiftly identify potential ear trauma caused by foreign bodies that could result in hearing loss or vestibular dysfunction. Clear and open communication facilitates rapid diagnosis and treatment decisions, particularly concerning the need for otolaryngology, anesthesia involvement, and patient sedation in complex cases. Ensuring the availability of the proper equipment and adequate clinical training will help prevent errors and support a coordinated response.

Roles within the team are well-defined. Clinicians provide clinical expertise to diagnose and treat adverse events promptly, tailoring interventions to the patient’s specific needs. Nursing staff closely monitor patient and family anxiety, reporting any concerns immediately, including the need for patient restraint or sedation. Effective communication and collaboration within the team are fundamental to ensuring a swift and comprehensive response that minimizes patient harm and optimizes healing if ear trauma has occurred. This coordinated effort ensures that patient safety remains the top priority in the management of foreign bodies in the ear.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Morris S, Osborne MS, McDermott AL. Will children ever learn? Removal of nasal and aural foreign bodies: a study of hospital episode statistics. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2018 Jul 3:100(8):1-3. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2018.0115. Epub 2018 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 29968507]

Ray R, Dutta M, Mukherjee M, Gayen GC. Foreign body in ear, nose and throat: experience in a tertiary hospital. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2014 Jan:66(1):13-6. doi: 10.1007/s12070-012-0529-2. Epub 2012 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 24605294]

Parajuli R. Foreign bodies in the ear, nose and throat: an experience in a tertiary care hospital in central Nepal. International archives of otorhinolaryngology. 2015 Apr:19(2):121-3. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1397336. Epub 2014 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 25992166]

Chiun KC, Tang IP, Tan TY, Jong DE. Review of ear, nose and throat foreign bodies in Sarawak General Hospital. A five year experience. The Medical journal of Malaysia. 2012 Feb:67(1):17-20 [PubMed PMID: 22582543]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceThompson SK, Wein RO, Dutcher PO. External auditory canal foreign body removal: management practices and outcomes. The Laryngoscope. 2003 Nov:113(11):1912-5 [PubMed PMID: 14603046]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchulze SL, Kerschner J, Beste D. Pediatric external auditory canal foreign bodies: a review of 698 cases. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002 Jul:127(1):73-8 [PubMed PMID: 12161734]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMarin JR, Trainor JL. Foreign body removal from the external auditory canal in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatric emergency care. 2006 Sep:22(9):630-4 [PubMed PMID: 16983246]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWhite AC, Shih MC, Nguyen SA, Carol Liu YC. Comparison of Care Settings for Pediatric External Auditory Canal Foreign Bodies: A Meta-Analysis. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2023 Mar:132(3):322-331. doi: 10.1177/00034894221093584. Epub 2022 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 35499131]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMehta GU, Lekovic GP, Maxwell AK, Brackmann DE, Slattery WH. Effect of Vestibular Schwannoma Size and Nerve of Origin on Posterior External Auditory Canal Sensation: A Prospective Observational Study. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2020 Oct:41(9):e1145-e1148. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002738. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32925858]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIsaacson B. Anatomy and Surgical Approach of the Ear and Temporal Bone. Head and neck pathology. 2018 Sep:12(3):321-327. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0926-2. Epub 2018 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 30069845]

El-Anwar MW, Fouad YA, Elgohary AF, Saber S, Mobasher MA. External Auditory Canal: Computed Tomography Analysis and Classification. International archives of otorhinolaryngology. 2023 Oct:27(4):e565-e570. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1758213. Epub 2023 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 37876695]

Falcon-Chevere JL, Giraldez L, Rivera-Rivera JO, Suero-Salvador T. Critical ENT skills and procedures in the emergency department. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2013 Feb:31(1):29-58. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2012.09.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23200328]

Tozoglu U, Caglayan F, Harorli A. Foramen tympanicum or foramen of Huschke: anatomical cone beam CT study. Dento maxillo facial radiology. 2012 May:41(4):294-7. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/62359484. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22517996]

Friedman EM. VIDEOS IN CLINICAL MEDICINE. Removal of Foreign Bodies from the Ear and Nose. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Feb 18:374(7):e7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMvcm1207469. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26886547]

Kadish H. Ear and nose foreign bodies: "It is all about the tools''. Clinical pediatrics. 2005 Oct:44(8):665-70 [PubMed PMID: 16211189]

Benger JR, Davies PH. A useful form of glue ear. Journal of accident & emergency medicine. 2000 Mar:17(2):149-50 [PubMed PMID: 10718247]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLou Z. The outcome and complication of endoscopic removal of pediatric ear foreign body. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2021 Jul:146():110753. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2021.110753. Epub 2021 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 33951543]

Das SK. Aetiological evaluation of foreign bodies in the ear and nose. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 1984 Oct:98(10):989-91 [PubMed PMID: 6491495]

Afolabi OA, Aremu SK, Alabi BS, Segun-Busari S. Traumatic tympanic membrane perforation: an aetiological profile. BMC research notes. 2009 Nov 21:2():232. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-232. Epub 2009 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 19930586]

Davies PH, Benger JR. Foreign bodies in the nose and ear: a review of techniques for removal in the emergency department. Journal of accident & emergency medicine. 2000 Mar:17(2):91-4 [PubMed PMID: 10718227]

Prasad N, Harley E. The aural foreign body space: A review of pediatric ear foreign bodies and a management paradigm. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2020 May:132():109871. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.109871. Epub 2020 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 32050118]

Nivatvongs W, Ghabour M, Dhanasekar G. Difficult button battery ear foreign body removal: the magnetic solution. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2015 Jan:129(1):93-4. doi: 10.1017/S0022215114003053. Epub 2014 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 25471385]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeffler S, Cheney P, Tandberg D. Chemical immobilization and killing of intra-aural roaches: an in vitro comparative study. Annals of emergency medicine. 1993 Dec:22(12):1795-8 [PubMed PMID: 8239097]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOyama LC. Foreign Bodies of the Ear, Nose and Throat. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2019 Feb:37(1):121-130. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2018.09.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30454775]

Yetiser S, Hidir Y, Birkent H, Satar B, Durmaz A. Traumatic ossicular dislocations: etiology and management. American journal of otolaryngology. 2008 Jan-Feb:29(1):31-6 [PubMed PMID: 18061829]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAnsley JF, Cunningham MJ. Treatment of aural foreign bodies in children. Pediatrics. 1998 Apr:101(4 Pt 1):638-41 [PubMed PMID: 9521948]