Introduction

Oxidative phosphorylation is a cellular process that harnesses the reduction of oxygen to generate high-energy phosphate bonds in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). It is a series of oxidation-reduction reactions that involve the transfer electrons from NADH and FADH2 to oxygen across several protein, metal, and lipid complexes in the mitochondria known as the electron transport chain (ETC). The electron transport chain utilizes NADH and FADH2 generated from several catabolic cellular processes. Also, oxidative phosphorylation utilizes elemental oxygen as the final oxidizing agent (and electron acceptor). Mitochondrial function and the electron transport chain shed light on the evolution and advancement of aerobic eukaryotic life, especially when compared to anaerobic organisms. It is the hallmark of aerobic respiration and is the reason why a plethora of lifeforms require oxygen to survive.[1][2][3]

Fundamentals

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Fundamentals

The process of oxidative phosphorylation involves understanding fundamental concepts: electronegativity, the sources of reduced NADH and FADH2, and the anatomy of the mitochondrion.

- Electronegativity is the ability of an elemental atom to attract a bonding pair of electrons. Elements with a high electronegativity can attract electrons to their atomic nuclei more easily. Fluorine is considered the most electronegative element; however, oxygen is also highly electronegative and has a low molecular mass. Given its greater availability in the atmosphere, elemental oxygen is used as the final electron acceptor in oxidative phosphorylation.

- NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) and FAD+ (flavin adenine dinucleotide) are free (non-membrane bound) electron carrier coenzymes that are present in the cell cytoplasm and mitochondrial matrix. They get reduced in several reactions, principally including glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (citric acid) cycle, and beta-oxidation of fatty acids. The reduction of NAD+ and FAD+ generates energy-rich NADH and FADH2 that are shuttled to the mitochondrion, delivering high energy electrons to the protein complexes in the electron transport chain.

- The mitochondrion consists of inner and outer membranes, both of which are composed of phospholipid bilayers and integral membrane proteins involved in enzymatic action and molecular transport. The inner membrane has inward-facing fold-like projections known as cristae that vastly increase the surface area of the membrane to maximize the amount of energy production. The protein complexes involved in the electron transport chain are studded along this membrane. The inner membrane envelops the matrix, which houses mitochondrial DNA, ribosomes, and a multitude of enzymes and metabolites. The space between the inner and outer membrane is known as the intermembrane space; this is the site of hydrogen ion deposition for the protein complexes in the electron transport chain. The increased hydrogen ion (H+ ion) concentration (and effectual decreased pH) generate a membrane potential across the inner mitochondrial membrane.[2][4][5][6][7]

Issues of Concern

Research into the secondary regulation of the electron transport chain (such as reversible phosphorylation of complexes), and the relationship of mitochondrial function to neuroplasticity has been underexplored. Through the exploration of such topics, the relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction and neurological pathology could be elucidated. By solidifying understanding of secondary mechanisms of regulation, the pathogenesis and clinical therapy of many diseases may be better understood.

Cellular Level

The exergonic process of electron transfer from NADH to oxygen couples with the endergonic process of ATP synthesis. Thus, catabolic reactions (that utilize ATP) get coupled with the anabolic reaction of ATP synthesis. Both reactions require each other to operate. Approximately 30 - 32 ATP molecules are generated from the electron transport chain, while the yield for glycolysis alone is only 2 ATP. ATP generation in oxidative phosphorylation is significantly greater than glycolysis alone, due to the efficiency of energy extraction in the electron transport chain (ETC).

The transfer of energy from reduced electron carriers to oxygen occurs through the pumping of hydrogen ions (also called proton or H+ ion) into the intermembrane space. This process is referred to as chemiosmosis because of the difference in H+ ion concentration between the intermembrane space and the mitochondrial matrix. The electrochemical gradient generated by H+ ions pumped into the intermembrane space is termed the ‘proton motive’ force.

To harness the proton motive force to generate ATP, ETC utilizes the final complex, ATP synthase (complex V). The energy expended from pumping H+ ions into the intermembrane space is equivalent to the energy generated by ATP synthase. Therefore, the first law of thermodynamics is maintained.[1][2][8][9]

Molecular Level

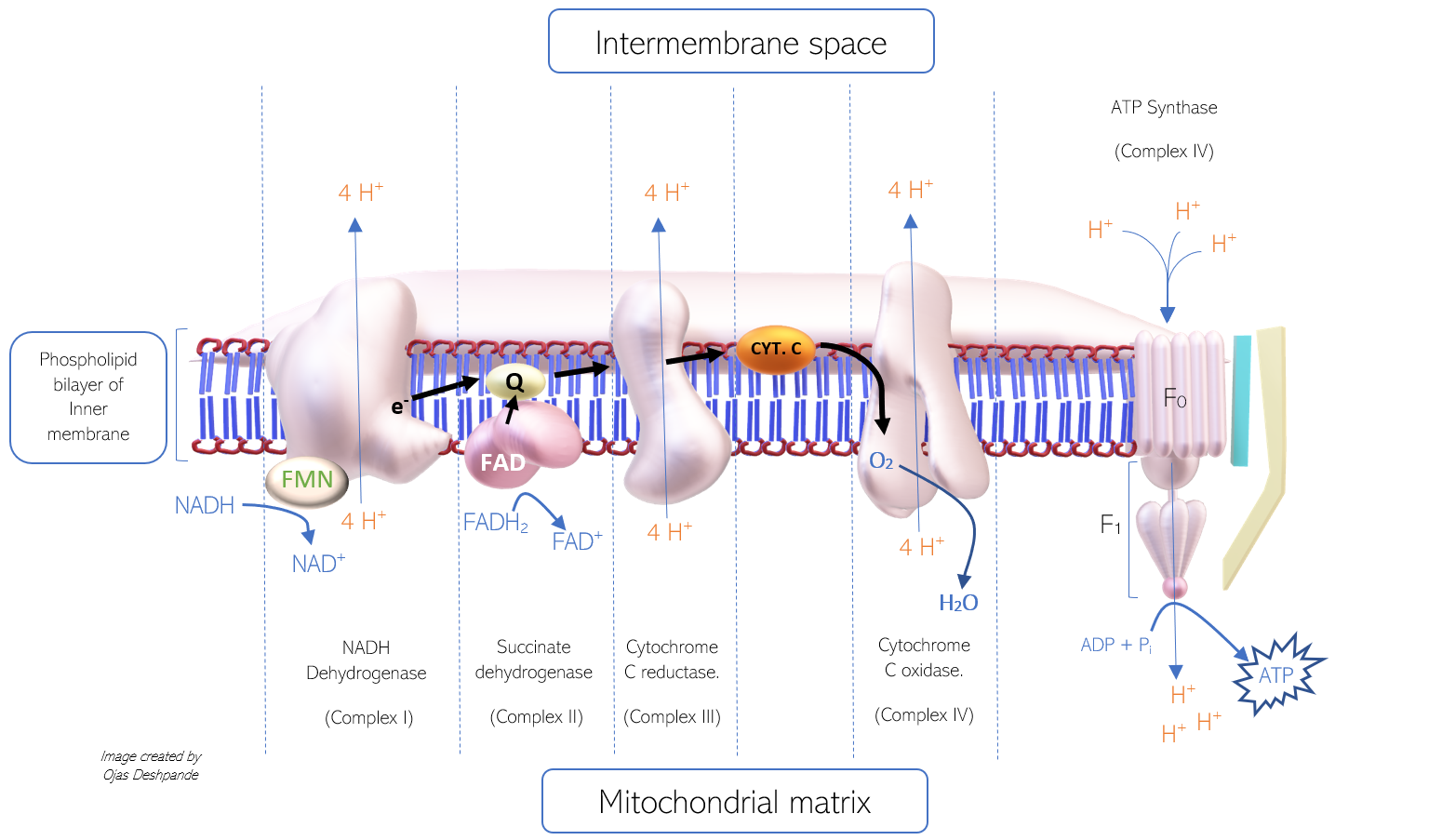

The process of electron transfer from NADH to protein complexes and finally to oxygen is intricate. There are four protein complexes involved in electron transfer that function as enzymes in the electron transport chain (ETC). These enzymes carry out oxidation and reduction reactions, permitting the transfer of electrons from one complex to the next in series. The complexes are named: Complex I, II, III, and IV. Complex V (ATP synthase) is functionally different, as it facilitates the generation of ATP (rather than electron transfer). Of the four complexes, complex I, III, and IV, all pump 4 protons into the intermembrane space. The mechanism of proton pumping involves conformational changes of the protein complex; however, the exact mechanism is still a topic of research. Each complex consists of several molecules, including iron-sulfur clusters (Fe-S), cytochromes, and prosthetic groups that all aid in the transfer of electrons.

The ETC shuttle electrons from one complex to the next, utilizing hydrophilic electron carriers, such as cytochrome C (that can travel freely through the intermembrane space) and hydrophobic, such as coenzyme Q10 (that can diffuse through the phospholipid bilayer of the inner membrane). The genetic information for the four complexes and the free electron carriers gets housed in both mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) and nuclear DNA.

- Coenzyme Q10 (Co Q10) has a hydrophobic benzoquinone structure that allows it to travel freely through the phospholipid bilayer. The oxidized form is referred to as ubiquinone (or Q). When reduced, Co Q10 simultaneously carries two hydrogen ions and an electron pair in the form of Ubiquinol (QH2). Upon arrival at the next protein complex in the ETC, ubiquinol once again oxidizes to ubiquinone.

- Cytochrome C is referred to as a cytochrome for its heme group structure. Cytochrome C contains an iron atom surrounded by a porphyrin ring. The reduction and oxidation of the iron atom (between Fe 2+ to Fe 3+ oxidation states) allow the cytochrome to carry individual electrons from one complex to another in the ETC.[10][11][12]

Mechanism

COMPLEX I

The first complex (complex I) in the ETC is referred to as NADH dehydrogenase, for its role in oxidizing NADH to NAD+. This complex has enzymatic activity that allows the transfer of an electron pair from NADH to ubiquinone (Q). An electron pair from NADH is first shuttled into NADH dehydrogenase by flavin mononucleotide (derived from riboflavin, or vitamin B2), an accompanying prosthetic group. Within the complex, the electron pair is transferred sequentially from one iron-sulfur cluster (Fe-S) to another, to reach ubiquinone eventually. Ubiquinone is then reduced to ubiquinol and travels to complex II. As the electrons pass from NADH to ubiquinone, energy is released and utilized by the complex to pump 4 H+ ions into the intermembrane space. The products of the enzymatic reaction include NAD+, Ubiquinol (reduced form of Co Q10), and 4 H+ ions in the intermembrane space.

COMPLEX II

The second complex (complex II) is referred to as succinate dehydrogenase, for its role in the oxidation of succinate to fumarate in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA). Note that this enzyme is involved in both the ETC and the TCA. It is also the point of electron transfer for FADH2. This enzyme transfers electrons from FADH2 to a ubiquinone molecule. This relatively small complex contains iron-sulfur clusters and a bound cofactor, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD). Both structures shuttle electrons from FADH2 to ubiquinone. However, not enough energy gets released in this process, and thus no H+ ions are pumped into the intermembrane space from this complex. Since FADH2 bypasses complex I and enters complex II directly, it does not contribute to the proton gradient as much as NADH does, which explains why there is a higher yield of ATP generated from NADH (about 2.5 ATP molecules) as compared to FADH2 (about 1.5 ATP molecules)

- Electrons from complex I and II are shuttled by ubiquinone (in the form of ubiquinol) to complex III.

COMPLEX III

The third complex (complex III) is referred to as Cytochrome c reductase, for its role in reducing cytochrome c. This complex consists of several molecules, including cytochrome B and many iron-sulfur clusters, all of which are involved in the shuttling of electrons to cytochrome c. The enzymatic action of complex III involves the transfer of electrons from ubiquinol to cytochrome c and subsequent pumping of 4 H+ ions into the intermembrane space. Although ubiquinol can deliver two electrons, cytochrome c can only accept one electron. Thus, Cytochrome c reductase exists in a dimeric form to accommodate two cytochrome c molecules. The process of cytochrome c reduction via complex III is the Q cycle.

COMPLEX IV

The fourth complex (complex IV) is referred to as Cytochrome c oxidase, for its role in the oxidation of cytochrome c. This highly complicated molecule consists of multiple heme groups, cofactors, and subunits. Metal ions in the heme groups (copper and iron) sequester an oxygen atom within the complex. The enzymatic action of complex IV permits the transfer of electrons from cytochrome c molecules to the oxygen atom, which functions as the last electron acceptor. During the reduction of oxygen, two H+ ions are extracted from the matrix and transferred to the reduced oxygen atom, thus forming water (H2O). Simultaneously, the complex pumps 4 H+ ions into the intermembrane space.

- It is important to note that the stepwise passing of electrons from one complex to the next is also driven by the stepwise increase in electronegativity of each complex.

COMPLEX V

This enzyme’s multi-subunit structure allows for the conversion of potential energy to mechanical and chemical energy, as the F1 subunit rotates (like a turbine) with the force of protons attempting to re-enter the matrix.

The fifth complex (complex V) is referred to as ATP synthase, for its role in the synthesis of ATP using the proton motive force. ATP synthase consists of numerous protein subunits, including F0 and F1. The F0 portion is hydrophobic, rooted in the phospholipid bilayer, and contains a channel for H+ ions to pass through to the F1 portion. The hydrophilic F1 portion (shaped like a stick attached to a cylinder) is the main catalytic site. It consists of a ring of rotating alpha and beta subunits surrounding a gamma subunit. H+ ions travel from the F0 portion to the F1 portion and, in turn, force the rotation of the F1 portion, which catalyzes the binding of ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) to produce ATP. This process is the binding-change phenomenon.[13][1][2][10]

Pathophysiology

A crucially important biochemical process involved in oxidative phosphorylation is the generation of a hydrogen ion gradient between the inner and outer membranes of the mitochondria, also referred to as the chemiosmotic gradient. The energy from this gradient (termed the proton-motive force) is what propels the production of ATP in the mitochondrial matrix. Many molecules have been found to disrupt or impede this process in some way, resulting in both clinical and non-clinical applications. Additionally, dysfunction of the electron transport chain results in a variety of diseases, ranging from metabolic (such as mitochondrial myopathies) to neurological (such as bipolar disorder) in nature.

Toxins and Drugs

Cyanide and carbon monoxide are known to irreversibly bind to and inhibit protein complex cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) of the electron transport chain, ceasing the production of ATP and resulting in cell death (and death of the entire organism at high enough concentrations). The sedative amobarbital, while a potent GABA agonist, also binds and inhibits NADH dehydrogenase, resulting in reduced ATP production.

Oxidative Stress

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a byproduct of the electron transport chain complexes that lead to cellular damage via the production and proliferation of free radicals such as peroxides (H2O2) and oxides (such as superoxide). ROS generated from the redox reactions within the four complexes contribute to cell membrane damage and cell senescence.

Mitochondrial Myopathy

Genetic mutations in mitochondrial DNA (such as MT-ND1) can produce defective complex I (NADH dehydrogenase). This defect will result in reduced production of ATP via oxidative phosphorylation. The macroscopic consequences of this mutation result in a syndrome known as MELAS (mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes). MELAS encephalopathies and myopathies result in symptoms of severe weakness, seizures, and several other symptoms that begin in childhood.

Another syndrome known as MERRF (myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers) involves the mutation of a variety of mitochondrial genes, resulting in malformation of many components of the mitochondrion, including the protein complexes of the ETC. The reduced ATP output through oxidative phosphorylation causes many severe clinical symptoms, including myoclonic epilepsy.[14][5][12][15][16]

Clinical Significance

Although most compounds that interfere with the ETC have a destructive function, some of them have genuine utility in the body. The uncoupling agent thermogenin is an H+ ion channel protein present in brown adipose (fat), which allows the passage of H+ ions from the intermembrane space back into the matrix. The rapid flow of H+ ions into the matrix generates heat and uncouples the ATP generating and ATP consuming reactions from each other by disrupting chemiosmosis (hence the term uncoupling agent). This heat is a significant contributor to maintaining core body temperature in neonates who would lose significant heat due to their high skin surface area to body volume ratio.[8]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Boyman L, Karbowski M, Lederer WJ. Regulation of Mitochondrial ATP Production: Ca(2+) Signaling and Quality Control. Trends in molecular medicine. 2020 Jan:26(1):21-39. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.10.007. Epub 2019 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 31767352]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNath S. Integration of demand and supply sides in the ATP energy economics of cells. Biophysical chemistry. 2019 Sep:252():106208. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2019.106208. Epub 2019 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 31238246]

Matlin KS. The Heuristic of Form: Mitochondrial Morphology and the Explanation of Oxidative Phosphorylation. Journal of the history of biology. 2016 Feb:49(1):37-94. doi: 10.1007/s10739-015-9418-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26238091]

Miranda-Quintana RA, Martínez González M, Ayers PW. Electronegativity and redox reactions. Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP. 2016 Aug 10:18(32):22235-43. doi: 10.1039/c6cp03213c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27451962]

Pehar M, Harlan BA, Killoy KM, Vargas MR. Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Metabolism and Neurodegeneration. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2018 Jun 20:28(18):1652-1668. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7145. Epub 2017 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 28548540]

Dereven'kov IA, Hannibal L, Makarov SV, Molodtsov PA. Catalytic effect of riboflavin on electron transfer from NADH to aquacobalamin. Journal of biological inorganic chemistry : JBIC : a publication of the Society of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2020 Feb:25(1):125-133. doi: 10.1007/s00775-019-01745-3. Epub 2019 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 31773269]

Bartolák-Suki E, Imsirovic J, Nishibori Y, Krishnan R, Suki B. Regulation of Mitochondrial Structure and Dynamics by the Cytoskeleton and Mechanical Factors. International journal of molecular sciences. 2017 Aug 21:18(8):. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081812. Epub 2017 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 28825689]

Rui L. Brown and Beige Adipose Tissues in Health and Disease. Comprehensive Physiology. 2017 Sep 12:7(4):1281-1306. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c170001. Epub 2017 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 28915325]

Vinogradov AD. New Perspective on the Reversibility of ATP Synthesis and Hydrolysis by F(o)×F(1)-ATP Synthase (Hydrolase). Biochemistry. Biokhimiia. 2019 Nov:84(11):1247-1255. doi: 10.1134/S0006297919110038. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31760915]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceScialò F, Fernández-Ayala DJ, Sanz A. Role of Mitochondrial Reverse Electron Transport in ROS Signaling: Potential Roles in Health and Disease. Frontiers in physiology. 2017:8():428. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00428. Epub 2017 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 28701960]

Gvozdjáková A, Kucharská J, Kura B, Vančová O, Rausová Z, Sumbalová Z, Uličná O, Slezák J. A new insight into the molecular hydrogen effect on coenzyme Q and mitochondrial function of rats. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology. 2020 Jan:98(1):29-34. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2019-0281. Epub 2019 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 31536712]

Al Ghouleh I, Khoo NK, Knaus UG, Griendling KK, Touyz RM, Thannickal VJ, Barchowsky A, Nauseef WM, Kelley EE, Bauer PM, Darley-Usmar V, Shiva S, Cifuentes-Pagano E, Freeman BA, Gladwin MT, Pagano PJ. Oxidases and peroxidases in cardiovascular and lung disease: new concepts in reactive oxygen species signaling. Free radical biology & medicine. 2011 Oct 1:51(7):1271-88. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.011. Epub 2011 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 21722728]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLetts JA, Sazanov LA. Clarifying the supercomplex: the higher-order organization of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2017 Oct 5:24(10):800-808. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3460. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28981073]

Neupane P, Bhuju S, Thapa N, Bhattarai HK. ATP Synthase: Structure, Function and Inhibition. Biomolecular concepts. 2019 Mar 7:10(1):1-10. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2019-0001. Epub 2019 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 30888962]

Vincent AE, Ng YS, White K, Davey T, Mannella C, Falkous G, Feeney C, Schaefer AM, McFarland R, Gorman GS, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM, Picard M. The Spectrum of Mitochondrial Ultrastructural Defects in Mitochondrial Myopathy. Scientific reports. 2016 Aug 10:6():30610. doi: 10.1038/srep30610. Epub 2016 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 27506553]

Sinnecker T, Andelova M, Mayr M, Rüegg S, Sinnreich M, Hench J, Frank S, Schaller A, Stippich C, Wuerfel J, Bonati LH. Diagnosis of adult-onset MELAS syndrome in a 63-year-old patient with suspected recurrent strokes - a case report. BMC neurology. 2019 May 8:19(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1306-6. Epub 2019 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 31068171]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence