Introduction

The thorax and pelvis surround a body space that is called the abdomen. The diaphragm forms the superior surface of the abdomen, and the pelvis forms the inferior surface.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The abdomen consists of the organs necessary for digestion. These include the stomach, pancreas, liver, gallbladder and small and large intestines. The abdomen also contains the kidneys and spleen. Connecting tissues called the mesentery, hold these organs together. The mesentery also allows these organs to move relative to one another and expand. The abdomen has a covering fascia, a layer of tissue that is protective. The abdominal muscles lay in front of the fascia, and on the outermost layer is the skin. The back of the abdomen consists of back muscles as well as the spine.

The junction where the abdomen ends and the pelvis begins is the lumbar region of the abdomen. The pelvis is composed of the bony pelvis, pelvic floor, pelvic cavity, and the perineum. The function of the pelvis is for structural support and stability.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Many important blood vessels lie in the abdomen and travel through. These include the aorta, inferior vena cava and the branches that come off of them. The abdominal aorta gives rise to the celiac trunk, which separates the left gastric artery, common hepatic artery, and the splenic artery. Next, the left and right renal arteries branch off laterally. The superior and inferior mesenteric artery come off the abdominal aorta anteriorly while the gonadal arteries branch off laterally.[1] Inferiorly towards the pelvis, the common iliac artery separates in the pelvic cavity.

In the pelvis, the common iliac artery separates into the internal and external iliac arteries.[2] The internal iliac artery provides the blood supply to the bladder and genital organs. The branches of the internal iliac artery include arteries that supply the bladder, obturator muscle, uterus, rectum, external genitalia, and gluteal muscles. The internal iliac vein joins with the external iliac vein and becomes the common iliac vein that drains into the inferior vena cava.[3]

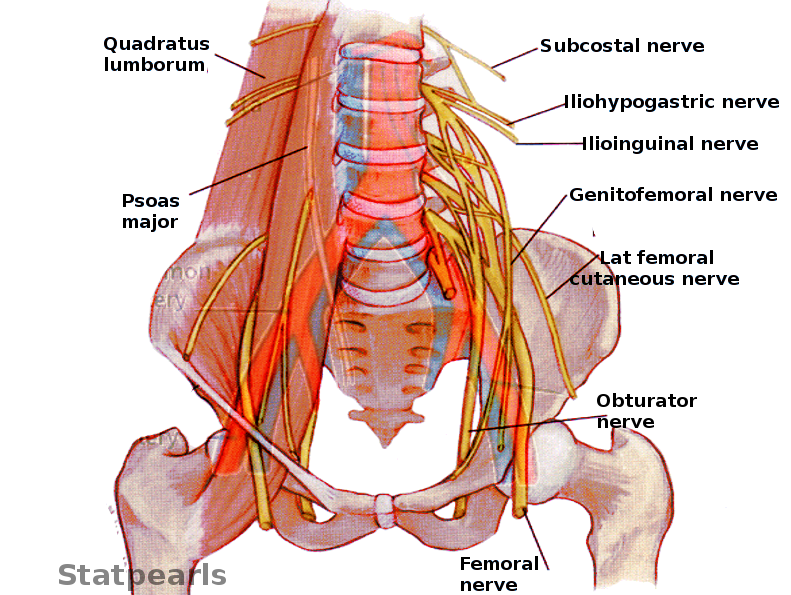

Nerves

The autonomic nerves (sympathetic and parasympathetic systems) supply the visceral peritoneum, whereas the parietal peritoneum has spinal nerves deriving the somatic innervation.[4] The visceral peritoneum senses dull, poorly localized pain when stretched out or distended and is associated with diaphoresis and nausea.[5] Thus, a patient may perceive a vague abdominal pain in a general region. However, when the parietal peritoneum is involved, patients experience a sharp, localized type of pain in a specific area.

Abdomen

- Left and right vagus nerve - parasympathetic innervation

- Gastric nerves

- Celiac plexus from spinal cord segments T6 to T9

- Subcostal nerve

- Iliohypogastric

Pelvis

- Pelvic splanchnic

- Femoral

- Obturator

- Ilioinguinal

- Genitofemoral

- Superior gluteal

- Inferior gluteal

- Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

- Coccygeal plexus from S4 and S5

- Sacral plexus from L4 through S4: sciatic nerve, pudendal nerve, gluteal nerves, nerve to obturator internus, nerve to piriformis

Muscles

The muscles of the abdomen, in conjunction with the muscles of the back, provide posture and stability, helping the spine remain erect and adjust the position of the body. In the anterior aspect of the abdomen, the most superficial muscle is the external oblique muscle. Located deep to the external oblique is the internal oblique muscle, which is much thinner. The transversus abdominis muscle is the deepest, and the fibers run transversely. All of these muscles contribute to the linea alba at the midline. On either side of the midline, the rectus abdominis muscles are the vertical muscles that are divided by the linea alba. The pyramidalis is a muscle at the base of the pubic bone that also attaches to the linea alba.[6]

The muscles of the abdomen and back attach to the pelvis and work together with the muscles of the pelvis. Some pelvic muscles such as psoas major and iliacus help flex the trunk and thigh. The inferior aspect of the pelvic cavity is called the pelvic diaphragm.[7] The muscles that make up the pelvis diaphragm are the piriformis, coccygeus, iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis.[8]

Physiologic Variants

Due to the variable nature of the abdominal organs, many different physiologic variants are fully functional and acceptable for survival. Studies have shown, however, that stomach shape and size can be affected by diet and eating habits. An increased amount of food taken daily can lead to an increase in the volume of the stomach. This change would be considered a physiologically large stomach and is reversible once diet intake decreases to a smaller amount.

The pelvis joints need to be relaxed during pregnancy to allow for mobility and to allow an increase in the pelvic measurements.[9] This physiologic change occurs during labor due to hormones, and these changes contribute to the process of labor and delivery. Some people have a narrower pelvis, termed the android pelvis, and others have a wider pelvis, named the gynecoid pelvis. Most males have the android pelvis as their bodies do not have the adaptation for giving birth. Most females have the gynecoid pelvis to assist in childbirth with minimal difficulty.[10]

Clinical Significance

The transition from periumbilical pain to lower right quadrant pain is seen in appendicitis and is explainable due to the autonomic nerve supply to the visceral peritoneum and the somatic innervation to the parietal peritoneum. Initially, the patients may complain of generalized epigastric pain. This sensation is due to the irritation of visceral peritoneum. As the inflammation progresses, the parietal peritoneum is irritated, leading to localized pain in the right lower quadrant area at the McBurney point.[11]

This concept also presents in the level of abdominal pain after eating fatty foods, which suggests a biliary origin of pain. The release of cholecystokinin leads to contraction of the gallbladder, and if the gallbladder is unable to empty bile due to obstruction from a gallstone, the distention of the gallbladder stretches the visceral peritoneum. This state of affairs leads to the classic right upper quadrant or epigastric pain. The right upper quadrant pain can be combined with scapular pain because the scapular pain arises from the phrenic nerve, as the gallbladder and the scapula share the same cutaneous dermatome.[12] When clinicians perform a physical exam and find Murphy sign, this is thought to be specific to acute cholecystitis. Palpating deep in the right upper quadrant causes the gallbladder to contact the parietal peritoneum, irritating it and causing cessation of inspiration due to the pain.

The difference between somatic and visceral pain is of clinical significance because somatic pain is due to peritoneal irritation and thus is well localized. On the other hand, visceral pain is more challenging to localize as a result of stretching of the visceral organs.

As suspected, the pelvic muscles are under tremendous strain during childbirth. Afterward, women are advised to perform Kegel exercises to help strengthen the pelvic floor muscles. If symptoms are refractory to less invasive treatment, surgery might be the solution. During childbirth, women can experience perineal trauma, such as lacerations. To prevent this, some obstetricians make a small incision, called an episiotomy, to potentially avoid spontaneous traumatic tears due to limited space for the baby to emerge.[13]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Shahoud JS, Miao JH, Bolla SR. Anatomy, Thorax, Heart Aorta. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30844167]

van de Luijtgaarden KM, Brehm V. External Iliac Artery Aneurysm Causing Severe Venous Obstruction. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2019 May:57(5):739. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.12.030. Epub 2019 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 30952513]

Teter K, Schrem E, Ranganath N, Adelman M, Berger J, Sussman R, Ramkhelawon B, Rockman C, Maldonado TS. Presentation and Management of Inferior Vena Cava Thrombosis. Annals of vascular surgery. 2019 Apr:56():17-23. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2018.08.082. Epub 2018 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 30982504]

Kalra A, Wehrle CJ, Tuma F. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Peritoneum. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521209]

Reymond MA. Founding of the International Society for the Study of Pleura and Peritoneum (ISSPP). Pleura and peritoneum. 2018 Sep 1:3(3):20180125. doi: 10.1515/pp-2018-0125. Epub 2018 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 30911665]

Sevensma KE, Leavitt L, Pihl KD. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Rectus Sheath. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725838]

Muavha DA, Ras L, Jeffery S. Laparoscopic surgical anatomy for pelvic floor surgery. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2019 Jan:54():89-102. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.11.005. Epub 2018 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 30554856]

Jelinek LA, Scharbach S, Kashyap S, Ferguson T. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Anterolateral Abdominal Wall Fascia. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083814]

Jarrell J. Demonstration of cutaneous allodynia in association with chronic pelvic pain. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2009 Jun 23:(28):. pii: 1232. doi: 10.3791/1232. Epub 2009 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 19550406]

Mike M, Kano N. Laparoscopic-assisted low anterior resection of the rectum--a review of the fascial composition in the pelvic space. International journal of colorectal disease. 2011 Apr:26(4):405-14. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-1107-2. Epub 2010 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 21190027]

Wang ZH, Ye J, Wang YS, Liu Y. Diagnostic accuracy of pediatric atypical appendicitis: Three case reports. Medicine. 2019 Mar:98(13):e15006. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30921220]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOppenheimer DC, Rubens DJ. Sonography of Acute Cholecystitis and Its Mimics. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2019 May:57(3):535-548. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2019.01.002. Epub 2019 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 30928076]

Diko S, Guiahi M, Nacht A, Connell KA, Reeves S, Bailey BA, Hurt KJ. Prevention and Management of Severe Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injuries (OASIs): a National Survey of Nurse- Midwives. International urogynecology journal. 2020 Mar:31(3):591-604. doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-03897-x. Epub 2019 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 30877353]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence