Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Bladder Detrusor Muscle

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Bladder Detrusor Muscle

Introduction

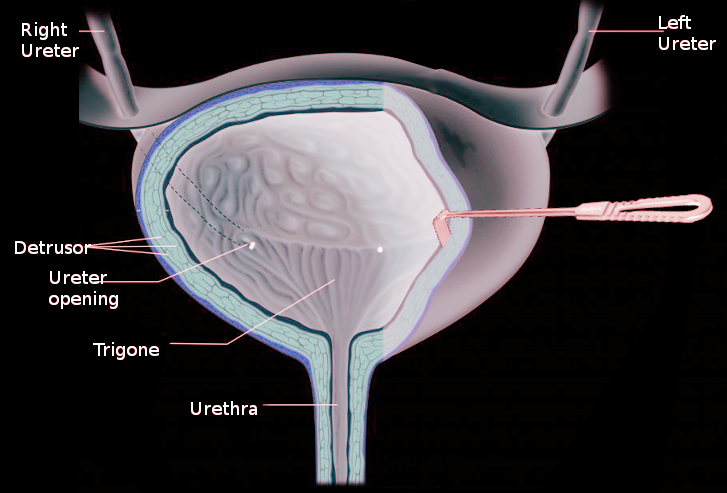

The walls of the bladder are mainly formed by detrusor muscle, which allows the bladder to contract to excrete urine or relax to hold urine. At the inferior end of the bladder, the detrusor muscle is continuous with the internal urethral sphincter. The combination of detrusor contraction and urethral sphincter relaxation leads to urination. The detrusor muscle is under control from the autonomic system and is composed of smooth muscle. Detrusor muscle pathology can lead to urinary retention, incontinence, or a combination of both. Abnormalities of the detrusor muscle, if left untreated, can lead to deterioration of the upper urinary tracts.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The wall of the bladder is comprised of smooth muscle fibers oriented in multiple different directions. These smooth muscle fibers are collectively known as the detrusor muscle. This interwoven orientation provides the bladder with the ability to stretch in response to the presence of urine. The primary function of the detrusor muscle is to contract during urination to push the urine out of the bladder and into the urethra. The detrusor muscle will relax to allow the storage of urine in the urinary bladder.

Embryology

The bladder is initially derived from the upper segment of the urogenital sinus in the fetus and connected with the allantois. However, the allantois eventually becomes obliterated to become the urachus leaving just the bladder. Detrusor smooth muscle is of both mesodermal and neural crest origin.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The upper portion of the urinary bladder is supplied primarily by the superior vesical artery, which is a branch of the hypogastric artery. The lower portion receives supply from the vaginal artery in females and by the inferior vesicular artery in males. There is minor blood supply via the inferior gluteal and obturator arteries as well. The venous system drains via the vesical venous plexus, which empties into the vesical veins. Vesical veins eventually lead to the internal iliac veins. The lymphatics of the bladder mostly drain into the external iliac lymph nodes.

Nerves

The detrusor muscle is under autonomic control. The parasympathetic nervous system stimulates the muscarinic stretch receptors in the bladder through the pelvic nerve fibers. When urine fills the bladder, the M3 receptors located within the bladder become stretched and stimulated, which leads to the contraction of the detrusor muscle for urination. At the same time, the parasympathetic fibers inhibit the internal urethral sphincter, which causes relaxation allowing for bladder emptying.

When the bladder empties of urine, the stretch fibers become inactivated, and the sympathetic nervous system is stimulated to activate the beta-3 receptors through the adenylyl cyclase-cAMP pathway in the bladder. This process is achieved via the hypogastric nerve, causing relaxation of the detrusor muscle. Newer beta-3 agonists utilize this pathway to treat bladder overactivity. During ejaculation, the sympathetic response leads to the contraction of the internal urethral sphincter to prevent the reflux of semen into the bladder. This response also prevents urine from passing during ejaculation. The most sensitive region of the bladder for the stretch receptors is the trigone.

Sensory fibers detect pain from overdistention. The center for coordinating urination is in the pons.[3][4]

Muscles

The detrusor muscle is located within the walls of the bladder and is composed of smooth muscle fibers that are longitudinal and circular. The layers of the detrusor muscle start longitudinally in the inner layer, become circular in the middle layer, and then longitudinal again in the outer layer. The muscle is continuous with the internal urethral sphincter, which is also composed of smooth muscle. The ureter passes obliquely through the detrusor muscle to prevent the reflux of urine into the kidney as the bladder fills. If this ureteral tunnel is not oblique or short, then urine can reflux into the kidney causing infections, renal scarring, and renal damage.

Physiologic Variants

Pediatric detrusor muscle has less contractility and has more passive stiffness compared to adult detrusor muscle; this is most likely due to a greater connective tissue to smooth muscle ratio in children, which is the bladder compliance (change in bladder pressure/change in bladder volume). Poor (decreased) bladder compliance is associated with upper urinary tract damage.

Surgical Considerations

Pelvic surgery may lead to bladder dysfunction. Some pelvic surgeries that have reported complications of bladder dysfunction include, but are not limited to, radical prostatectomy, perineal resection, radical hysterectomy, and proctocolectomy. Surgeons should take caution during pelvic surgery to avoid damage to any nerves, vessels, or structures of the bladder or urinary system.[5][6]

Clinical Significance

Patients with urinary retention usually present with difficulty voiding, a sensation of incomplete emptying, urinary retention, frequent voiding, and overflow incontinence. Diabetes mellitus and other neurologic conditions such as a stroke are the leading causes of detrusor nerve control degeneration.

Detrusor areflexia is the inability of the bladder to contract, which is typically neurologic in origin. Some causes of detrusor areflexia include spinal cord injury, fractures, herniated disc, and infections.

Damage to the detrusor muscle from chronic overdistention can lead to the fibrosis of the muscle with weakness in the contraction of the muscle. This condition is often referred to as a myogenic bladder.

A common cause of chronic bladder distension is benign prostatic hypertrophy in males and less commonly severe pelvic organ prolapse in females. Whether the issue is of nerve or muscle origin, poor emptying ability is the result.

A subset of women may have detrusor overactivity with poor contractility, which can lead to overflow incontinence. This condition is common in the aging female population. Detrusor overactivity is often associated with urgency incontinence. Urgency incontinence is the sudden urge to urinate, which may lead to leakage. Urgency incontinence is common in older women with other comorbid diseases. Treatment of the underlying disease is the most effective treatment. Usually, the first steps in treatment involve conservative options with lifestyle modifications, pelvic floor exercises, and bladder training. However, if these initial conservative therapies do not improve symptoms, there are other pharmacologic and surgical therapies. The two medication classes commonly used are antimuscarinic drugs such as oxybutynin and tolterodine or beta 3-adrenergic drugs such as mirabegron. Antimuscarinics have side effects such as dry mouth, constipation, blurry vision, drowsiness, and cognitive issues. Sacral nerve stimulation and Botox are other options. More invasive therapies include surgery with augmentation cystoplasty or detrusor myectomy, which improves compliance of the bladder. This limits or prevents upper tract damage resulting from high bladder pressures.[2][7][8]

Other Issues

Bladder cancer is among the most common cancers of the urinary system. It typically presents in older patients with painless hematuria, urinary frequency, urgency, and dysuria. Bladder cancer is diagnosed and staged by doing a cystoscopy with biopsy. The depth of invasion of the cancer is a crucial factor in determining therapy and prognosis.

When cancer spreads to the submucosa or lamina propria, it is considered a T1 lesion. There are multiple therapies for T1 bladder cancer. These include transurethral resection, intravesical therapy, and surveillance. However, when cancer invades past the submucosa into the detrusor muscle, it will be considered a T2 lesion; this is muscle-invasive bladder cancer and is a very important distinction when it comes to therapies because T2 lesions have an increased risk of nodal and distant metastasis. Thus, when cancer invades the detrusor muscle, the standard of treatment is the removal of the urinary bladder (radical cystectomy) and the diversion of the urine. Urinary diversion involves the creation of a bowel conduit or neobladder by harvesting a bowel segment. Finally, T3 lesions are when the tumor extends past the muscle into the perivesical fat, and T4 lesions occur when the tumor spreads to nearby organs.[9]

Media

References

Abelson B, Sun D, Que L, Nebel RA, Baker D, Popiel P, Amundsen CL, Chai T, Close C, DiSanto M, Fraser MO, Kielb SJ, Kuchel G, Mueller ER, Palmer MH, Parker-Autry C, Wolfe AJ, Damaser MS. Sex differences in lower urinary tract biology and physiology. Biology of sex differences. 2018 Oct 22:9(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13293-018-0204-8. Epub 2018 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 30343668]

Fitz F, Sartori M, Girão MJ, Castro R. Pelvic floor muscle training for overactive bladder symptoms - A prospective study. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira (1992). 2017 Dec:63(12):1032-1038. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.63.12.1032. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29489983]

Andersson KE. On the Site and Mechanism of Action of β(3)-Adrenoceptor Agonists in the Bladder. International neurourology journal. 2017 Mar 24:21(1):6-11. doi: 10.5213/inj.1734850.425. Epub 2017 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 28361520]

Purves JT, Spruill L, Rovner E, Borisko E, McCants A, Mugo E, Wingard A, Trusk TC, Bacro T, Hughes FM Jr. A three dimensional nerve map of human bladder trigone. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2017 Apr:36(4):1015-1019. doi: 10.1002/nau.23049. Epub 2016 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 27265789]

Iguchi N, Malykhina AP, Wilcox DT. Early life voiding dysfunction leads to lower urinary tract dysfunction through alteration of muscarinic and purinergic signaling in the bladder. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2018 Nov 1:315(5):F1320-F1328. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00154.2018. Epub 2018 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 30089034]

Yoshida M, Yamaguchi O. Detrusor Underactivity: The Current Concept of the Pathophysiology. Lower urinary tract symptoms. 2014 Sep:6(3):131-7. doi: 10.1111/luts.12070. Epub 2014 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 26663593]

Radadia KD, Farber NJ, Shinder B, Polotti CF, Milas LJ, Tunuguntla HSGR. Management of Postradical Prostatectomy Urinary Incontinence: A Review. Urology. 2018 Mar:113():13-19. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.09.025. Epub 2017 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 29031841]

Aoki Y, Brown HW, Brubaker L, Cornu JN, Daly JO, Cartwright R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2017 Jul 6:3():17042. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.42. Epub 2017 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 28681849]

El-Achkar A, Souhami L, Kassouf W. Bladder Preservation Therapy: Review of Literature and Future Directions of Trimodal Therapy. Current urology reports. 2018 Nov 3:19(12):108. doi: 10.1007/s11934-018-0859-z. Epub 2018 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 30392150]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence