Introduction

The purpose of peripheral nerve blocks is to inhibit impulse transmission distally in a nerve terminal, thus terminating the pain signal perceived by the cortex. Nerve blocks can be used to treat acute pain (e.g., procedural anesthesia and perioperative analgesia), as well as for diagnosis and treatment of chronic pain. Impulse blockade can be brief (hours) or prolonged (months), depending on the medication used in the block and the technique (e.g., single-shot block versus catheter). Nerve blocks are also useful in the emergency department for the following indications: Acute pain management of the extremities.[1][2][3]

- Anesthesia of the extremity for procedures

- Alternative to procedural sedation

- Alternative to opioids in certain patient populations (e.g., a head injury patient, patients with concomitant mental status change, patients on buprenorphine)

Many nerves can be blocked depending on the injury. These include the following upper or lower extremities:

- Brachial plexus roots at the interscalene location block the shoulder, upper arm, elbow, and forearm.

- Brachial plexus trunks at the supraclavicular location block the upper arm, elbow, wrist, and hand.

- Brachial plexus cords at the infraclavicular location block the upper arm, elbow, wrist, and hand.

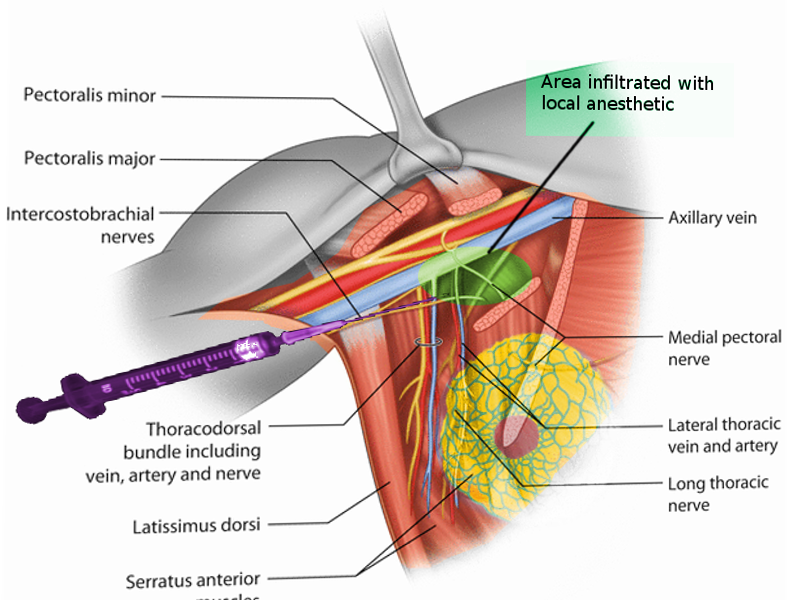

- Brachial plexus branches at the axillary location block the forearm, wrist, hand, and elbow, including the musculocutaneous nerve.

- The median nerve at the elbow blocks the hand and forearm.

- The radial nerve at the elbow blocks the hand and forearm.

- The ulnar nerve at the elbow blocks the hand and forearm.

- The femoral nerve at the femoral crease blocks the anterior thigh, femur, knee, and skin anesthesia over the medial aspect of the leg below the knee.

- The sciatic nerve at the subgluteal location or anterior approach below the femoral crease blocks the posterior aspect of the thigh and the anterior, lateral, and posterior lower leg, ankle, and foot.

- The sciatic nerve at the popliteal location blocks the anterior, lateral, and posterior lower leg, ankle, and foot.

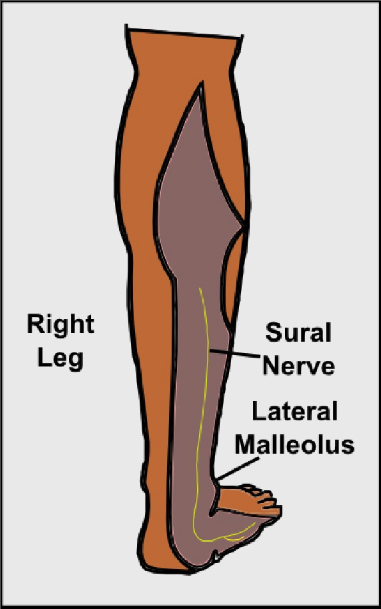

- Ankle block of five separate nerves to the ankle and foot (saphenous nerve, deep peroneal nerve, superficial peroneal nerve, posterior tibial nerve, and sural nerve) blocks the entire foot.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

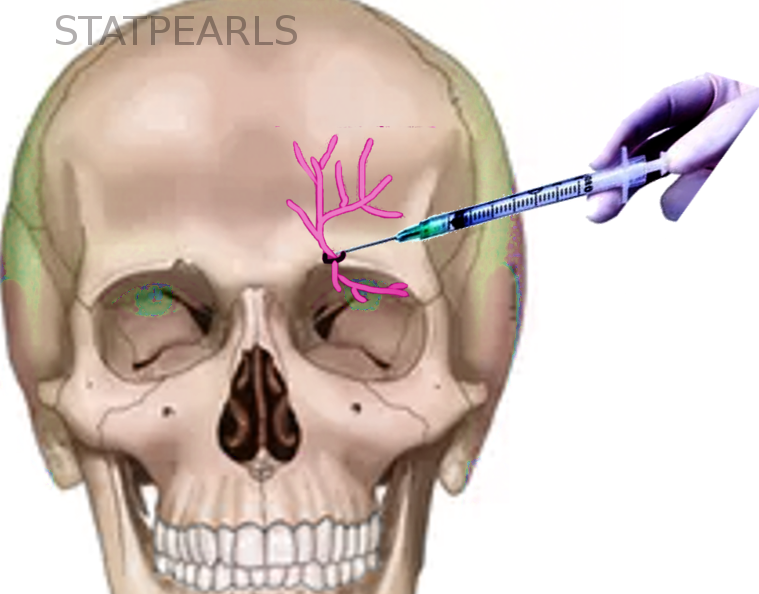

Peripheral nerve blocks have gained widespread acceptance as technological advancements have improved accuracy, efficacy, and safety. Nonetheless, in-depth knowledge of peripheral nerve anatomy remains an essential component of a successful and safe peripheral nerve blockade. Peripheral nerve blocks were originally performed by eliciting paresthesias to localize peripheral nerves, followed years later by nerve stimulation techniques. More recently, ultrasound guidance has improved anesthesiologists’ and emergency physicians' abilities to visualize nerve structures and other surrounding structures (e.g., vasculature and pleura).[4][5]

Epidemiology

Peripheral nerve blocks offer many advantages to traditional anesthetic and analgesic techniques. Patients who would otherwise have excessive risks with general anesthesia can safely undergo surgery painlessly with regional anesthesia. Additionally, perioperative opioid analgesia's adverse effects can be minimized or avoided entirely while still providing superior pain control. If a prolonged blockade is a goal, peripheral nerve catheters can remain for several days to provide more extended analgesia than a single-shot block alone.

Pathophysiology

Although peripheral nerve blocks are overall safe when performed correctly, there are rare but serious risks associated with them. Risks include block failure, bleeding, infection, damage to surrounding structures, permanent nerve injury, and intravascular uptake of local anesthetic resulting in systemic toxicity. Contraindications include an inability to cooperate with placement (sometimes seen in pediatric patients, combative patients, or those with severe dementia), pre-existent neurologic deficit, systemic or active local infection at the site of the block, body habitus, or obesity obscuring optimal ultrasonographic visualization. Relative contraindications include the presence of coagulopathy.

Toxicokinetics

Local anesthetics have a significant risk of systemic toxicity when administered intravascularly. Symptoms usually manifest in the central nervous system first (metallic taste, auditory changes, circumoral numbness, blurred vision, agitation, seizures), followed by cardiovascular effects (hypotension, decreased cardiac contractility, dysrhythmias, complete heart block, cardiovascular collapse). Bupivacaine is particularly cardiotoxic, and reports of cardiovascular collapse in the absence of antecedent neurologic symptoms exist. Neurolytic blocks with alcohol and phenol have utility in chronic pain but are usually the last resort in cancer pain. They cause semi-permanent destruction of the nerve, which blocks impulse transmission and improves pain. Risks with neurolytic destruction of a nerve include the development of central or deafferentation pain syndromes, which are very difficult to treat.[6][7][8]

Contraindications include an allergy to aminoesters (procaine, cocaine, tetracaine).

Amides-lidocaine/bupivacaine/mepivacaine/ropivacaine (usually preservative).

History and Physical

Before performing a peripheral nerve block, a complete history and physical exam are essential. The emphasis in the patient's history should be on the existence of underlying severe cardiac or pulmonary disease, opioid intolerance, pre-existing neurologic deficit, easy bleeding or bruising, and anticoagulation medications. The physical exam should direct its focus to the sensory and motor function of the extremity undergoing blockade, evidence of coagulopathy (e.g., widespread bruising), evidence of systemic infection (fever or elevated white blood cell count), and infection at the site of the block (redness, swelling, warmth).

Evaluation

A thorough risk/benefit analysis and informed consent are necessary when evaluating a patient for peripheral nerve blockade. If block administration is in the emergency department, discussion with the anesthesiology can help direct preference toward a catheter if a longer block duration is preferable. Each patient’s maximum local anesthetic dose must be calculated before performing the block and never exceeded.

Treatment / Management

Emergency airway equipment, resuscitation drugs (including lipid emulsion 20%), supplemental oxygen, and hemodynamic monitoring must be immediately available where blocks are performed. Blocks should be administered with a strict sterile technique. Anxiolytic medications may be used to facilitate patient comfort. Awake patients reduce the risk of nerve injury by reporting paresthesias so the needle can be redirected before injection of local anesthetic. Additionally, an awake patient can report early symptoms of local anesthetic systemic toxicity (i.e., tinnitus, circumoral numbness, and tachycardia with epinephrine) to avoid more serious complications that can occur a large volume local anesthetic injection (seizures, coma, and cardiac collapse). Recommended maximum dosages for local anesthetics are widely available, but practitioners should always use the lowest dose necessary to achieve the desired result due to the significant risk of systemic toxicity.

Point of care, bedside ultrasound, can be used to locate and visualize the nerve.

Differential Diagnosis

- Anaphylaxis

- Anxiety disorders

- Cocaine toxicity

- Conversion disorders

Complications

Potentially serious complications resulting from peripheral nerve blocks include nerve injury, infections at the catheter site, bleeding, and local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST). Other effects can include elevations of blood sugar, itching, rash, and injection site soreness.[9]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should receive explanations about the potential adverse effects of the procedure. They should also be told what to expect from the procedure, including discomfort at the site of catheterization, numbness of the body part affected, and the nerve block duration. The clinician can also answer any other patient questions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Peripheral nerve blocks can be performed by any physician as long as they are familiar with the anatomy. However, if a complication occurs, early recognition and treatment are essential to reduce long-term morbidity to the patient. Intravenous lipid emulsion 20% must immediately be available in locations that perform peripheral nerve blocks. Patients with a suspected local anesthetic overdose should be treated immediately with intravenous lipid emulsion 20% (Intralipid) 1.5 mL/kg (lean body mass) given over one minute, followed by a 0.25 mL/kg/min infusion. Refractory cases of local anesthetic systemic toxicity may require cardiopulmonary bypass/extracorporeal membrane oxygenation until the metabolism of the drug is complete.

Media

(Click Video to Play)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rao S, Rao S. Glossopharyngeal Nerve Block: The Premolar Approach. Craniomaxillofacial trauma & reconstruction. 2018 Dec:11(4):331-332. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606249. Epub 2017 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 30574279]

McPhee AS, McKay AC. Dorsal Penile Nerve Block. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571010]

Bonifacio CC. The efficacy of articaine and lidocaine local anaesthetic in child patients. Evidence-based dentistry. 2018 Dec:19(4):105-106. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6401340. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30573862]

Knipfer C, Rohde M, Oetter N, Muench T, Kesting MR, Stelzle F. Local anaesthesia training for undergraduate students - how big is the step from model to man? BMC medical education. 2018 Dec 14:18(1):308. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1389-6. Epub 2018 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 30547783]

Pandit JJ, Meek T. Nerve block site marking - a reply. Anaesthesia. 2019 Jan:74(1):125. doi: 10.1111/anae.14528. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30511760]

Pollard R, Higham H, Quinlan J, Webster R, Lie J, Sivasubramaniam S. Nerve block site marking. Anaesthesia. 2019 Jan:74(1):123-124. doi: 10.1111/anae.14527. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30511750]

Coraci D, Loreti C, Padua L. Peripheral Nerve Blocks for Hand Procedures. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Nov 29:379(22):2181-2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1813329. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30499644]

Shah R, Maizels M, Meade P, Suresh S. Regional nerve blocks in everyday pediatric urology: 2. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthetic caudal block. Journal of pediatric urology. 2018 Oct:14(5):457-460. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.11.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30502061]

Steinfeldt T, Kessler P, Vicent O, Schwemmer U, Döffert J, Lang P, Mathioudakis D, Hüttemann E, Armbruster W, Sujatta S, Lange M, Weber S, Reisig F, Hillmann R, Volk T, Wiesmann T. [Peripheral truncal blocks-Overview and assessment]. Der Anaesthesist. 2020 Dec:69(12):860-877. doi: 10.1007/s00101-020-00809-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32620990]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence