Anatomy, Head and Neck, Sinus Function and Development

Anatomy, Head and Neck, Sinus Function and Development

Introduction

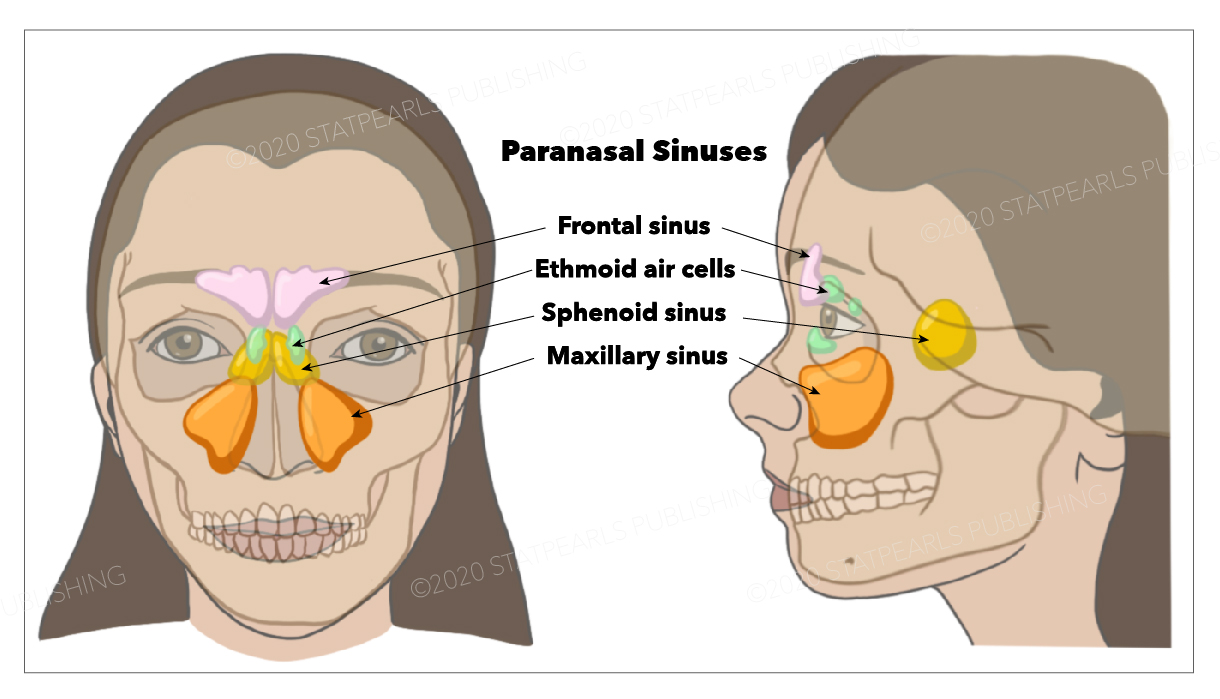

The paranasal sinuses (the hollow spaces in the skull and facial bones around the nose) are air-filled cavities within the frontal, ethmoidal, sphenoidal, and maxillary bones.[1] They are outgrowths from the nasal cavity. All of them drain into the superior or lateral aspect of the nose.[2] The sinuses' lining mucosa is continuous with the nasal cavity; therefore, any infections from the nasal mucosa can easily spread to the sinuses.[3] See Image. Nasal Cavity.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

There are 4 pairs of the paranasal sinuses:

- Maxillary sinuses (the biggest)

- Frontal sinuses

- Ethmoidal air cells

- Sphenoid sinus

The pyramid-shaped maxillary sinuses are located within the body of the maxilla. The apex of the sinus extends into the zygomatic process of the maxilla, and the lateral wall of the nose forms the base. The roof is formed by the floor of the orbit, while the alveolar process forms the floor. These sinuses are located at just above the level of the first and second premolars and of the third molar, and sometimes the root of the canine, bilaterally. It drains into the middle meatus of the nose via the hiatus semilunaris. The sinus readily accumulates fluid because the ostium as a drainage point is located high on the medial wall of the sinus.[4]

The frontal sinuses, which are separated from each other by a thin bony lamella, lie within the frontal bone. They are triangular in shape and extend upward above the medial end of the supraorbital crest and backward into the medial part of the orbit. Each frontal sinus drains into the middle meatus of the nose via infundibulum.[3]

The ethmoidal sinuses are variable in both size and the number of small cavities within the ethmoid labyrinth of the ethmoid bone. A collection of air cells (3 to 18) are located between the nose and the orbit. The lamina papyracea, which is a thin, orbital plate of the ethmoid bone, separates the sinuses from the orbit. The ethmoid sinuses are divided into 3 groups of cells by bony basal lamellae. The most important of these lamellae is the basal lamellae of the middle turbinate, which separates the ethmoid from the anterior and posterior groups with different drainage pathways.[5][6]

The sphenoidal sinuses lie within the body of the sphenoid bone. They are located at the most posterior (farthest toward the back of the head) of the paranasal sinuses. Each sinus opens into the sphenoethmoidal recess, which is above the superior concha.[3] See Image. Anatomical Positioning of Sinuses.

The paranasal sinuses have a wide variety of functions, including lightening the weight of the head, humidifying and heating inhaled air, increasing the resonance of speech, and serving as a crumple zone to protect vital structures in the case of facial trauma (see Image. Paranasal Sinuses). Most sinuses are absent or rudiments in newborns; extend into the regarding bones during childhood and reach their mature size in the early 20s; and their shape and development vary greatly, and they enlarge slowly until death.[3]

Embryology

The embryological development of the nasal cavities and sinuses is related to each other. Although the origin of the sinuses is the same, they develop at different times.[7]

During the 25 to 28 weeks of the intrauterine period, 3 horizontal protrusions originating from the lateral wall of the nose are the beginning of the formation of the maxillary and ethmoidal sinuses. The maxillary sinus is formed by the inferior projection, which is called maxilloturbinate. Ethmoidal air cells and their corresponding drainage channels are formed by the superior projection called ethmoid turbinate. The maxillary sinuses are rudimentary at birth. They enlarge after the eighth year and occur completely during adolescence. Because the drainage pathway of the paranasal sinuses passes through the ethmoid sinus or is adjacent to its lateral wall, it is regarded as a "keystone" in all paranasal sinuses. Ethmoidal air cells (or sinuses) are not present at birth, but they can be recognized using computed tomography (CT) scan until 2 years of age. Phylogenetically, the ethmoid sinus is not considered a true paranasal sinus because it is related to olfactory function and does not have pneumatization.[8]

The frontal sinus may develop with the migration of anterior ethmoidal air cells to the area between the outer and inner laminae of the frontal bone or as the direct continuation of the embryonic infundibula and the frontal recess at the 16th gestational week. It reaches adulthood size in adolescence.[9][10]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial Supply and Lymphatic Drainage of the Maxillary Sinuses

The arterial supplies are from the facial, infraorbital, and greater palatine arteries, and their venous drainage is into the facial, infraorbital, and greater palatine veins. The lymphatics of the maxillary sinuses drain to the submandibular nodes.[3]

Arterial Supply and Lymphatic Drainage of the Frontal Sinuses

The blood vessels are the supraorbital and anterior ethmoidal arteries and supraorbital and superior ophthalmic veins. The lymphatic drainage is to the submandibular nodes.[3]

Arterial Supply and Lymphatic Drainage of the Ethmoidal Sinuses

Both external and internal carotid systems provide the arterial blood supply of the ethmoid sinuses. The ophthalmic artery, one of the ethmoid sinus arteries, is part of the internal carotid system, the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries, and the sphenopalatine artery are part of the external carotid system. Their venous drainage is by the corresponding veins. The lymphatic drainage of the anterior and the middle ethmoidal cells are to the submandibular node. The lymphatics of the posterior ethmoidal cells drain to the retropharyngeal nodes.[11][12]

Arterial Supply and Lymphatic Drainage of the Sphenoidal Sinuses

The arterial supply is from the posterior ethmoidal artery and venous drainage through the corresponding vein. The lymphatic drainage is to the retropharyngeal nodes.[13][14]

Nerves

The nerve supply of the maxillary sinuses is from the infraorbital and the anterior, middle, and posterior superior alveolar nerves.[15]

The nerve supply of the frontal sinuses is from the supraorbital nerve.[16]

The sensorial nerve supply of the ethmoidal cells is from the anterior and posterior ethmoidal nerves nerve. The parasympathetic secretomotor fibers of these sinuses are from orbital branches of the pterygopalatine ganglion.[16]

The sensorial nerve supply of the sphenoidal sinuses is from the posterior ethmoidal nerves, and its parasympathetic secretomotor fibers are from orbital branches of the pterygopalatine ganglion.[16]

Clinical Significance

Sinusitis may occur as a combination of frontomaxillary, frontoethmoidal, or ethmoidal, sphenoidal sinusitis, as well as individual sinuses. Maxillary sinusitis is the most common sinus infection. The most significant symptom of maxillary sinusitis is suborbital pain spreading to the teeth. Pressure on the infra-orbital nerve exacerbates this pain.

The frontal sinusitis produces pain in the suborbital and frontal regions. The orbital rim, the superior medial corner of the orbit, and the root of the nose are sensitive to the touch because of the supra-orbital nerve. Patients feel the pressure on their faces and head.

An anterior headache behind the nose characterizes ethmoidal sinusitis. In the patient with anterior ethmoiditis, purulent discharge drains into the middle meatus of the nasal fossa, while in the posterior ethmoiditis patient, mucus discharge drains into the olfactory fissure and the superior meatus. Chronic ethmoid sinusitis attacks contribute to the formation of nasal polyps.

Headaches often extend to the occiput and is a more deeply felt pain in the sphenoidal sinusitis. The purulent discharge drains into the rhinopharynx from the sphenoethmoidal recess. Unlike other sinusitis types, patients rarely blow their noses.[17]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

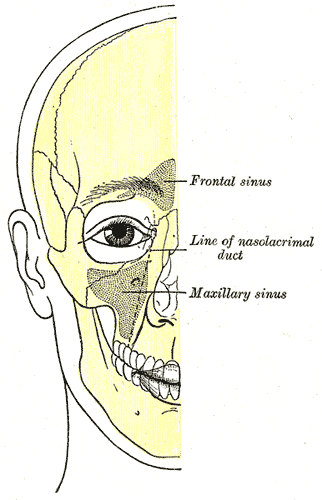

Anatomical Positioning of Sinuses. Illustrated image depicting the facial bone outline, highlighting the positions of air sinuses, including the frontal sinus, line of the nasolacrimal duct, and the maxillary sinus.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Nuñez-Castruita A, López-Serna N, Guzmán-López S. Prenatal development of the maxillary sinus: a perspective for paranasal sinus surgery. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2012 Jun:146(6):997-1003. doi: 10.1177/0194599811435883. Epub 2012 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 22267494]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVaid S, Vaid N. Normal Anatomy and Anatomic Variants of the Paranasal Sinuses on Computed Tomography. Neuroimaging clinics of North America. 2015 Nov:25(4):527-48. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2015.07.002. Epub 2015 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 26476378]

Henson B, Drake TM, Edens MA. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Nose Sinuses. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020644]

Cavalcanti MC, Guirado TE, Sapata VM, Costa C, Pannuti CM, Jung RE, César Neto JB. Maxillary sinus floor pneumatization and alveolar ridge resorption after tooth loss: a cross-sectional study. Brazilian oral research. 2018 Aug 6:32():e64. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2018.vol32.0064. Epub 2018 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 30088551]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZha Y, Lv W, Gao YL, Zhu ZZ, Gao ZQ. [Design of cross-sectional anatomical model focused on drainage pathways of paranasal sinuses]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology, head, and neck surgery. 2018 May:32(9):683-686. doi: 10.13201/j.issn.1001-1781.2018.09.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29771086]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiu J, Dai J, Wen X, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Wang N. Imaging and anatomical features of ethmomaxillary sinus and its differentiation from surrounding air cells. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2018 Feb:40(2):207-215. doi: 10.1007/s00276-018-1974-8. Epub 2018 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 29368251]

Kuntzler S, Jankowski R. Arrested pneumatization: witness of paranasal sinuses development? European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2014 Jun:131(3):167-70. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2013.01.008. Epub 2014 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 24709406]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePohunek P. Development, structure and function of the upper airways. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2004 Mar:5(1):2-8 [PubMed PMID: 15222948]

Villarreal R, Wrobel BB, Macias-Valle LF, Davis GE, Prihoda TJ, Luong AU, McMains KC, Weitzel EK, Yao WC, Brunworth J, Clark DW, Nair S, Valdés CJ, Halderman A, Jang DW, Sivasubramaniam R, Zhang Z, Chen PG. International assessment of inter- and intrarater reliability of the International Frontal Sinus Anatomy Classification system. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2019 Jan:9(1):39-45. doi: 10.1002/alr.22200. Epub 2018 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 30216705]

Demiralp KO, Kursun Cakmak S, Aksoy S, Bayrak S, Orhan K, Demir P. Assessment of paranasal sinus parameters according to ancient skulls' gender and age by using cone-beam computed tomography. Folia morphologica. 2019:78(2):344-350. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2018.0089. Epub 2018 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 30280374]

Bird B, Stawicki SP. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Ophthalmic Arteries. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29493942]

Turri-Zanoni M, Arosio AD, Stamm AC, Battaglia P, Salzano G, Romano A, Castelnuovo P, Canevari FR. Septal branches of the anterior ethmoidal artery: anatomical considerations and clinical implications in the management of refractory epistaxis. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2018 Jun:275(6):1449-1456. doi: 10.1007/s00405-018-4964-x. Epub 2018 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 29600317]

D P, Prabhu LV, Kumar A, Pai MM, Kvn D. The anatomical variations in the neurovascular relations of the sphenoid sinus: an evaluation by coronal computed tomography. Turkish neurosurgery. 2015:25(2):289-93. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.10638-14.0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26014015]

Praweswararat P. Cholesterol Granule of the Ethmoid Sinus: A Case Report. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet. 2016 Feb:99 Suppl 2():S220-2 [PubMed PMID: 27266241]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBahşi I, Orhan M, Kervancıoğlu P, Yalçın ED. Morphometric evaluation and surgical implications of the infraorbital groove, canal and foramen on cone-beam computed tomography and a review of literature. Folia morphologica. 2019:78(2):331-343. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2018.0084. Epub 2018 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 30178457]

Shumway CL, Motlagh M, Wade M. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Orbit Bones. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285385]

Pipolo C, Saibene AM, Felisati G. Prevalence of pain due to rhinosinusitis: a review. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2018 Jun:39(Suppl 1):21-24. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3336-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29904833]