Introduction

Rheumatological manifestations often occur alongside endocrine diseases and can precede endocrinopathy. Notable examples are seen in diabetes, thyroid diseases, parathyroid disorders, and hemochromatosis.[1] Diabetes is frequently associated with a broad spectrum of rheumatological manifestations due to persistent hyperglycemia's potential to induce inflammatory responses and disrupt immune cell function. Flexor tenosynovitis of the hand, diabetic cheiroarthropathy, adhesive shoulder capsulitis, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, Charcot neuroarthropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, and diabetic muscle infarction are the most common rheumatological manifestations of diabetes.[2][3]

Thyroid diseases, including Hashimoto thyroiditis and hyperthyroidism, are among the most common causes of concomitant rheumatological manifestations, including myopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, myxedema arthropathy, gout, and pseudogout.[4][5][6] Musculoskeletal manifestations in parathyroid disorders range from 13% to 93% and can present with osteitis fibrosa and calciphilaxis. Hemochromatosis is a disease characterized by excessive iron deposition in the tissues and can present with arthropathy in early or late presentations of the disease. Recognizing the association and coexistence between metabolic disorders and different rheumatological manifestations is crucial to prevent long-term complications.[7]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Diabetes Mellitus

The accumulation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and fibroproliferative complications in type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus has been associated with increased uptake by the receptor for AGE in the chondrocyte and tendon cell membranes. This mechanism activates pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6, which increase vascular endothelial growth in tendons and joints.[8]

Thyroid Disease

Autoimmune thyroid disease and rheumatic diseases exhibit increased expression of human leukocyte antigens DR4, DR3, and B8. Graves disease and chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis yield elevated antinuclear antibodies. Uncontrolled hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism have been associated with most rheumatological manifestations.

Parathyroid Diseases

Primary hyperparathyroidism, characterized by hypercalcemia and elevated parathyroid hormone levels, underscores musculoskeletal manifestations driven by aberrations in the Wnt pathway, contributing to erosive synovitis, arthralgias, and pseudogout. Calciphylaxis, a rare complication of hyperparathyroidism, involves arteriolar calcification due to elevated calcium and phosphate levels associated with fetuin-A deficiency.[9]

Hemochromatosis

Hemochromatosis arises from excessive iron deposition in different organs, with manifestations that can overlap with rheumatological and metabolic disorders. Primary iron overload is chiefly inherited, with hereditary hemochromatosis being the most common form linked to mutations in the HFE gene, particularly C282Y and H63D. A newer classification system categorizes hemochromatosis into HFE-related and non-HFE-related types, with secondary iron overload typically arising from blood transfusions or excessive dietary intake.[10]

Epidemiology

Diabetes Mellitus-Related Rheumatological Manifestations

Diabetes mellitus has a wide variety of rheumatologic manifestations. An estimated 30% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus experience carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), which can worsen with coexisting polyneuropathy and long-term uncontrolled glycemia. CTS currently remains the most common rheumatological manifestation of diabetes. Severe neuropathy initiates neuropathic osteoarthropathy (Charcot joint), a destructive joint disorder that affects 0.1% to 0.9% of individuals with diabetes.[11]

Adhesive shoulder capsulitis, a progressive, painful restriction in the range of motion of the glenohumeral joint, is present in 10% to 22% of patients with advanced, uncontrolled diabetes.[12] Flexor tenosysivitis, also known as the trigger finger, affects 5% to 10% of patients.[13] Other complications include diabetic muscle infarction, which frequently affects patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and is more common in men than women.[14]

Thyroid Disease-Linked Rheumatological Manifestations

Among thyroid diseases, hypothyroidism can present with multiple rheumatological manifestations. The condition affects women more than men and is usually observed between ages 40 and 70. Among common rheumatological manifestations, hypothyroid myopathy can affect around 79% of hypothyroid patients. Median nerve compression, a manifestation of CTS, has been found in 5% to 80% of cases of uncontrolled hypothyroidism.[15] Other conditions associated with hypothyroidism are osteoarthritis, myxedema, arthropathy, and pseudogout. Thyroid acropachy, a rare extrathyroidal condition, affects 1% of patients with Graves disease. [16]

Parathyroid Disease-Related Rheumatological Manifestations

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is the 3rd most common endocrine disorder after diabetes and thyroid disorder and can affect 2 to 7 per 1000 adults.[17] Musculoskeletal manifestations in PHPT range from 13% to 93%. Pseudogout is a PHPT complication that occurs several years after parathyroid resection.[18] Osteitis fibrosa cystica is a rare but clinically significant bone disorder associated with excessive parathyroid hormone levels. Calciphylaxis, a rare but life-threatening disease, is associated with secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism.[19]

Hemochromatosis-Associated Rheumatological Manifestations

Hemochromatosis, which can cause various metabolic and rheumatological symptoms, affects nearly 16 million Americans, either through inherited or acquired forms. Arthritis, the most common rheumatological manifestation of hemochromatosis, occurs in 45% of people with this disease.[20]

Histopathology

Only 2 of the various rheumatological manifestations observed in metabolic diseases require biopsy: calciphylaxis and DMI. The decision to perform a biopsy depends on the certainty of the clinical diagnosis.

Calciphylaxis

The dermis and epidermis typically develop ulcers and necrosis. Small and medium-sized blood vessel calcification may be present, with fibrosed and intravascular thrombi seen in the vessel's intimal layer. The pathognomonic feature is a diffuse calcification of small capillaries in the adipose tissue.

Diabetic Muscle Infarction

A biopsy usually reveals the presence of muscle necrosis and edema seen in DMI. Fibrosis and muscle fiber regeneration with lymphocytic infiltration are visible in the advanced stages of diabetes.

History and Physical

Rheumatological Manifestations of Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes can lead to a myriad of musculoskeletal complications that impact joint and soft tissue health. These conditions often present with symptoms such as pain, stiffness, and limited range of motion and can markedly compromise daily functioning and quality of life.

Flexor tenosynovitis of the hand

Flexor tenosyvonitis (trigger finger) is a mechanical condition affecting the metacarpophalangeal joints' flexor tendons. A mismatch between the size of the flexor tendons and the sheath leads to the formation of hard nodules in the area. The condition is characterized by finger locking and a decreased range of motion. Flexor tenosyvonitis presents with contractures, causing pain and swelling. Dupuytren contractures may arise from chronic and untreated flexor tenosynovitis.[21][22]

Diabetic cheiroarthropathy

Diabetic cheiroarthropathy, or limited joint mobility syndrome, is painless stiffness of the hands and fingers that severely impairs the range of motion of affected joints. The prayer and tabletop signs are clinical tests with high diagnostic sensitivity for diabetic cheiroarthropathy. The prayer sign clinical test is performed with the patient putting their hands flat against each other as if in prayer. Significant spaces between the patient's hands suggest flexion contractures (see Image. Prayer Sign). The tabletop sign has the patient placing their hand on the table at a 90° angle with the forearm. The test is positive if no contact is detected. Diabetic cheiroarthropathy is also associated with skin fibrosis, resulting in the appearance of tight, waxy skin.[23][24]

Adhesive shoulder capsulitis

Adhesive capsulitis, also termed "frozen shoulder," is a painful condition that limits the active and passive range of motion in the shoulders owing to the accumulation of collagen and other extracellular components that destroy the joint. The glenohumeral joint is the most affected. The evaluation should start with an extensive shoulder history.[25]

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is an asymptomatic disease that may be detected incidentally with radiography. DISH is characterized by the calcification and subsequent ossification of ligaments and entheses. The diagnosis is based on the presence of ossification in 4 contiguous vertebrae, disc height preservation, degenerative changes, and ankylosis at the facet-joint interface. DISH frequently mimics ankylosing spondylitis and degenerative spondylosis. Back pain and stiffness are the most common symptoms, but severe cases may also include dysphagia and bony reactions in the pelvis, patella, and calcaneus.[26]

Charcot neuroarthropathy

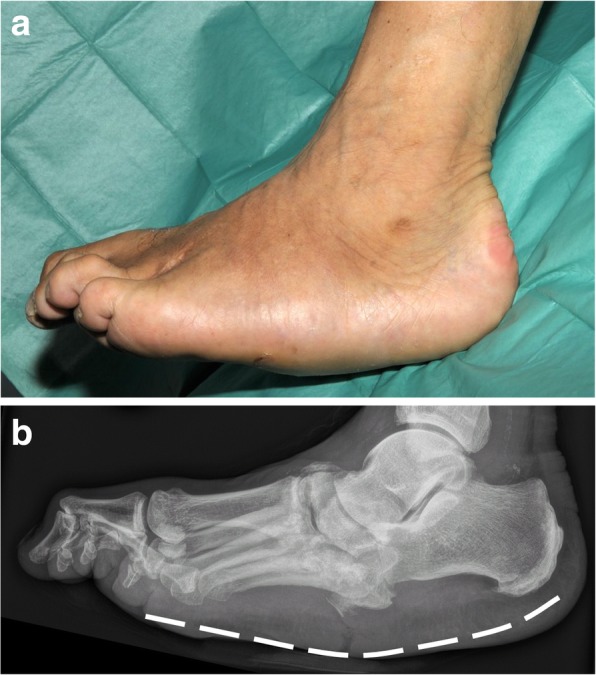

Charcot neuroarthropathy is a chronic, destructive disease of the bone structure and joints. Patients present with a long history of neuropathy before the diagnosis. Foot joints are most frequently affected, but Charcot neuroarthropathy may also impact the knee, wrist, and, in rare cases, the spine. The diagnosis presents several clinical challenges. Patients are typically asymptomatic, but the disease can mimic ankle sprains, cellulitis, inflammatory arthritis, and venous thrombosis. Acute Charcot neuroarthropathy manifests clinically as swelling, redness, and tenderness to palpation in the affected joint. In contrast, chronic Charcot neuroarthropathy can manifest as painless bone deformation, also known as rocker bottom feet.[27]

Carpal tunnel syndrome

CTS involves median nerve compression, leading to neuropathy. Patients frequently experience numbness, tingling, and pain in areas innervated by the medial nerve, ie, the thumb and the second, third, and radial portion of the fourth finger. The symptoms vary in intensity but tend to worsen at night. Advanced disease can cause sensory loss and muscle deformation due to weakness. Several maneuvers are used to diagnose CTS. The carpal compression test is positive if paresthesia or pain is evident after applying pressure to the carpal tunnel for 30 seconds. The test has a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 83%. The Phalen test is positive when pain and paresthesia are present when the patient flexes and holds their hands together for 1 minute. This test has a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 73%.[28]

Diabetic muscle infarction

DMI is a microangiopathic complication of uncontrolled diabetes. Patients typically report acute, severe pain without a history of trauma. A physical examination reveals a palpable mass.[29]

Rheumatological Manifestations of Thyroid Diseases

Certain thyroid disorders can lead to extrathyroidal manifestations affecting various tissues and organs. These manifestations can present with diverse symptoms, such as myxedematous changes in the extremities and muscle weakness, significantly impacting patients' physical capabilities and overall quality of life.

Thyroid acropachy

Thyroid acropachy is an extrathyroidal manifestation in patients with Graves disease. This condition presents as bilateral myxedematous changes to the hands, fingers, feet, and shins. Imaging reveals soft tissue and digital swelling.[30]

Hypothyroid myopathy

Hypothyroidism impairs muscle metabolism. Hypothyroid myopathy can present as nonspecific myalgias that intensify with physical activity. Patients often exhibit proximal myopathy, characterized by symmetric proximal muscle weakness. The hip and shoulder muscles are the most frequently affected.

Rheumatological Manifestations of Parathyroid Diseases

Parathyroid disorders can lead to significant complications in various tissues and organs, manifesting as painful lesions, bone deformities, and muscle weakness. These conditions often present with severe symptoms and require comprehensive management to address the underlying hormonal imbalances and prevent further complications.

Osteitis fibrosa

Osteitis fibrosa is a rare cystic bone destruction disorder caused by excess parathyroid hormone activity. The condition is common in patients with end-stage renal disease and chronic kidney disease. Patients may exhibit bone pain, fractures, and muscle weakness accompanied by hyperreflexia. Bone deformities may also be observed.[31]

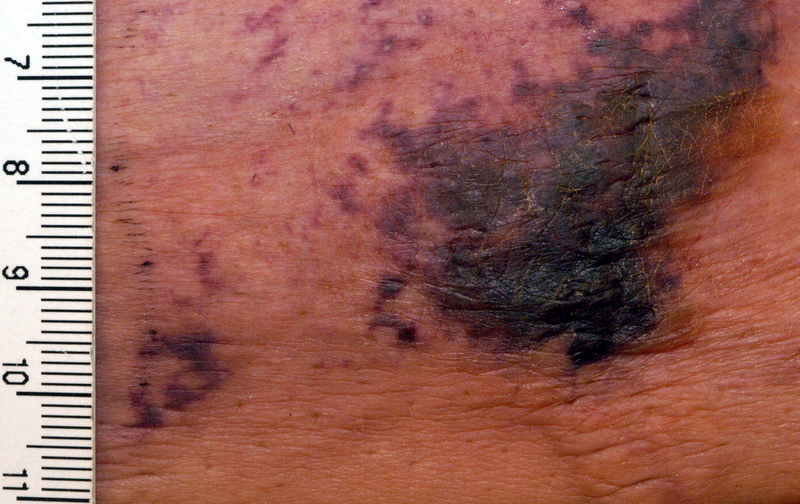

Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is characterized by extremely painful ischemic skin lesions. Skin lesions can sometimes appear as livedo reticularis or subcutaneous nodules. Progression can appear as necrosis and eschar. Calciphylaxis may also involve other organs (see Image. Calciphylaxis).

Arthropathy of Hemochromatosis

Hemochromatosis-related joint pain disease, which can clinically resemble rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, can present with joint swelling and pain in the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints. Other affected areas include the hip, which can present as severe and disabling hip joint pain.[32]

Evaluation

Diagnosing rheumatologic complications of metabolic diseases involves a combination of clinical evaluations, imaging studies, and laboratory tests. Accurate identification of these complications is crucial for differentiating them from primary rheumatic disorders and guiding appropriate treatment strategies.

Flexor Tenosynovitis

Diagnosis typically relies on physical examination. However, ultrasonography of the carpal tunnel can reveal thickening of the flexor tendon sheath surrounded by anechoic areas.

Diabetic Cheiroarthropathy

The diagnosis relies on physical examination and normally does not require radiography. Key clinical tests include the prayer sign and tabletop sign, which help assess the presence of flexion contractures and limited joint mobility.

Adhesive Shoulder Capsulitis

The diagnosis is based on clinical history. X-rays may occasionally be ordered to rule out similarly presenting conditions like fractures. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect synovitis, hypertrophy of the coracohumeral ligaments, and fat loss.

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

Radiographic findings include the characteristic sign called “flowing candle wax,” represented by nonmarginal syndesmophytes coming horizontally from the vertebrae. MRI and computed tomography are typically unnecessary for the diagnosis as they may lead to confusion with metastatic conditions.

Charcot Neuroarthropathy

Staging is according to the Eichenhotlz classification, the stages of which entail the following (see Image. Charcot Arthropathy):

- Stage 0: Normal radiography

- Stage 1: Bone debris at joints, fragmentation of subchondral bone, joint subluxation, or fracture-dislocation

- Stage 2: Absorption of bone debris with new bone formation, coalescence of large fragments with sclerosis of bone ends, some increased stability

- Stage 3: Remodeling of affected bones and joints, also known as reconstruction

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Diagnosis typically involves maneuver tests. Electromyography aids in assessing nerve damage and prognosis. Imaging is reserved for excluding structural abnormalities like tumors or ganglion cysts.

Diabetic Muscle Infarction

The initial assessment involves ruling out deep venous thrombosis. Laboratory findings may reveal elevated white blood cells, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and creatinine kinase levels. MRI is the preferred imaging modality to rule out differential diagnoses such as abscess or myopathy. MRI typically demonstrates uniform low-intensity signals in T1 with enhanced contrast in intermuscular fat, known as T2 hyperintensity. A biopsy may be necessary post-MRI for a definitive diagnosis.

Thyroid Acropachy

Imaging modalities may demonstrate soft tissue swelling and digital swelling. An x-ray may reveal new bone formation in the periosteum.

Hypothyroid Myopathy

Diagnosis relies on clinical findings and elevated inflammatory markers. An MRI may be necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

Osteitis Fibrosa

Radiography is essential for diagnosis, revealing diffuse demineralization and pathological fractures in the long bones of the extremities and a characteristic “salt and pepper” appearance in the skull. Subperiosteal bone erosions, appearing as sclerotic or lytic lesions, are present in the distal phalanges and lateral middle phalanges. Long bones may appear thin and almost absent.

Calciphylaxis

The definitive diagnosis is a skin biopsy of the lesions. Histology usually shows medial or small calcification of dermal arterioles with some fibrointimal hyperplasia, microthrombi, and vascular narrowing. Lesion biopsy may cause complications such as bleeding, infection, and necrosis. Assessing circulating fetuin-A levels has also been suggested to evaluate calciphylaxis.

Hemochromatosis-Related Arthropathy

The diagnosis depends on clinical manifestations and radiographic findings such as subchondral cysts, hook-like osteophytes affecting more of the metacarpophalangeal joint, and symmetric loss of joint space.

Treatment / Management

Treatment for rheumatologic complications of metabolic diseases involves a multifaceted approach suited to the specific condition. Management strategies include conservative measures such as medication, physical therapy, and lifestyle modifications, with surgical interventions reserved for severe or refractory cases. Effective treatment aims to alleviate symptoms, improve function, and address underlying metabolic abnormalities.

Flexor Tenosynovitis of the Hand

The initial conservative management involves using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and applying a wrist splint to the affected hand. Injections of platelet-rich plasma or glucocorticoids may be considered if conservative treatment fails. However, injectable corticosteroids are not recommended due to their limited efficacy and potential to induce hyperglycemia in individuals with uncontrolled diabetes. Tenosynovectomy is recommended if symptoms persist.

Diabetic Cheiroarthropathy

Treatment involves achieving glycemic control, physiotherapy, and occupational therapy to enhance hand mobility. Regular monitoring of joint flexibility and function is essential to track progress and adjust therapies as needed, ensuring optimal management of this condition.

Adhesive Shoulder Capsulitis

Adhesive capsulitis is self-limited in most cases. The necessary treatment focuses on symptom relief and improving range of motion. Physical therapy is indispensable during recovery, though vigorous rehabilitation can worsen symptoms. Intraarticular steroid injections and surgery are used for refractory cases.[33](B2)

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

The cornerstones are physical therapy, lifestyle modifications, NSAIDS, and bisphosphonates, depending on disease severity. Surgical decompression may be necessary for fractures, lumbar stenosis, and bone deformities.

Charcot Neuroarthropathy

Conservative management aims to restrict weight-bearing to prevent further deformity. Nonoperative approaches include off-loading with total non-weight-bearing or protective weight-bearing devices. Bisphosphonates may be used in the acute phase. Surgical options are considered if conservative management fails. Procedures include exostectomy, tenotomy, and isolated or multiple fusions with external or internal fixation.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

The initial CTS treatment involves conservative management, which includes wrist splints and oral NSAIDs. Glucocorticoid injections may be considered if conservative management is ineffective. Surgical intervention is available if symptoms have started affecting the quality of life and are not improving with conservative management.[34]

Diabetic Muscle Infarction

Treatment is conservative, with bed rest and analgesia. DMI recurrences involving the original or contralateral limb are present in 21% of the cases.

Thyroid Acropachy

Treatment options are limited. Systemic immunosuppressive therapy and local corticosteroids may be considered for associated ophthalmopathy and dermopathy.

Hypothyroid Myopathy

The treatment for hypothyroid myopathy is hypothyroidism management. Hormone replacement therapy addresses the underlying thyroid hormone deficiency, alleviating musculoskeletal complications. Regular monitoring of thyroid function and clinical symptoms guides treatment adjustments to optimize patient outcomes.

Osteitis Fibrosa

Parathyroidectomy is the treatment for osteitis fibrosa. Addressing renal disease and vitamin D deficiency can lead to the regression of brown tumors and symptoms.

Calciphylaxis

Hypercalcemia control is the cornerstone of calciphylaxis. Cinacalcet activates vitamin D in secondary hyperparathyroidism, avoiding hypercalcemia and elevated phosphorus levels. Wound care is pivotal to preventing infections.

Hemochromatosis-Associated Arthropathy

Treatment of hemochromatosis has few effects on the improvement of arthralgias or radiological changes. Management primarily focuses on controlling iron levels through therapeutic phlebotomy or chelation therapy to prevent further joint damage and systemic complications.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of rheumatic manifestations of metabolic diseases includes primary rheumatic conditions and musculoskeletal disorders secondary to other systemic processes, as indicated below (see Tables. Rheumatological Manifestations in Diabetes and Mimicking Conditions; Rheumatological Manifestations in Thyroid Diseases and Mimicking Conditions; Rheumatological Manifestations in Parathyroid Disorders and Mimicking Conditions; and Rheumatological Manifestations in Hemochromatosis and Mimicking Conditions). Differentiation between these conditions requires careful consideration of clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and imaging studies to identify the underlying cause and guide appropriate treatment strategies accurately.

Table. Rheumatological Manifestations in Diabetes and Mimicking Conditions

| Rheumatological manifestations in diabetes | Mimics |

| Charcot arthropathy | Gout, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis |

| Adhesive capsulitis | Osteoarthritis |

| Diabetic infarct muscle | Deep venous thrombosis, abscess, and cellulitis |

| Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis | Ankylosis spondylitis |

Table. Rheumatological Manifestations in Thyroid Diseases and Mimicking Conditions

| Rheumatological manifestations in thyroid diseases | Mimics |

| Thyroid acropachy | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Hypothyroid myopathy | Polymyositis, polymyalgia rheumatica |

| Hashimoto thyroiditis | Rheumatoid arthritis |

Table. Rheumatological Manifestations in Parathyroid Disorders and Mimicking Conditions

| Rheumatological manifestations in parathyroid disorders | Mimics |

| Calciphylaxis | Vasculitis |

| Osteitis fibrosa | Malignancy, osteomalacia, and infection |

Table. Rheumatological Manifestations in Hemochromatosis and Mimicking Conditions

| Rheumatological manifestations in hemochromatosis | Mimics |

| Arthropathy | Osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis |

Prognosis

The prognosis for rheumatological manifestations of metabolic disorders generally varies depending on the specific disorder, severity of joint involvement, and effectiveness of treatment. In many cases, achieving optimal control of the underlying metabolic disorder can significantly improve rheumatological symptoms and outcomes. Some manifestations, such as diabetic cheiroarthropathy, require physiotherapy to improve mobility and function.

However, some rheumatological manifestations may be chronic and progressive, necessitating long-term management and monitoring. For example, severe, advanced DISH or Charcot neuroarthropathy often causes significant disability and reduced quality of life. Overall, early diagnosis and comprehensive management of endocrinopathy can improve the prognosis and decrease long-term complications. Close collaboration between rheumatologists, endocrinologists, and other specialists is often necessary to optimize patient outcomes.

Complications

Metabolic disease-associated rheumatological disorders can be complex and varied, often presenting challenges in diagnosis and management. One of the most common complications is misdiagnosis, leading to functional impairment at the time of diagnosis. Joint damage and chronic pain can significantly impact the patient's quality of life. Addressing these complications requires an interprofessional approach involving various specialists, such as rheumatologists, endocrinologists, nephrologists, and neurologists, to provide comprehensive care tailored to each patient's specific needs.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventing rheumatological manifestations requires adherence to prescribed treatments that specifically control underlying metabolic conditions. For patients with T1DM and T2DM, blood glucose control through medication, diet, exercise, and regular glucose monitoring must be emphasized. Proper foot care to prevent complications should be discussed during every primary care physician appointment. Regular foot inspections, wearing supportive footwear, and avoiding barefoot walking must be encouraged.

For patients with thyroid complications, follow-up appointments are required to ensure optimal thyroid hormone levels. Proper management of thyroid replacement therapy is fundamental. Endocrinopathy management should include education about the signs and symptoms of rheumatological manifestations of metabolic disorders, such as joint stiffness, swelling, pain, and changes in skin texture. Controlling diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and parathyroid disorders can prevent further complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts regarding rheumatological manifestations of metabolic disorders include the following:

- Control of metabolic disorders can prevent rheumatological manifestations.

- A good clinical evaluation is the cornerstone for distinguishing between rheumatological and metabolic disorders.

- An interprofessional team approach is often necessary to recognize the overlap between rheumatological and metabolic disorders and ensure patients receive appropriate treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Rheumatological conditions frequently overlap with metabolic disorders in clinical practice, presenting diagnostic challenges due to their similar symptoms. Rheumatological manifestations are often misdiagnosed or overlooked, underscoring the importance of an interprofessional approach involving endocrinology, orthopedics, and rheumatology. Collaboration among these specialties is the cornerstone for achieving accurate diagnosis and effective treatment strategies. By pooling expertise from different domains, healthcare professionals can conduct comprehensive assessments, consider various differential diagnoses, and tailor management plans to address each patient's unique needs.

Shared decision-making emerges as a pivotal component of this collaborative effort, empowering patients to participate actively in their care journey. Informed by thorough discussions and mutual understanding, decisions regarding diagnostic tests, treatment options, and long-term management must align with patients' preferences, values, and goals. Effective communication acts as the glue that binds this interprofessional team together, facilitating the exchange of insights, resolution of uncertainties, and care coordination. Through regular consultations, interprofessional meetings, and shared electronic health records, healthcare professionals ensure that no aspect of the patient's condition is overlooked and interventions are seamlessly integrated across specialties.

The interprofessional approach, characterized by collaboration, shared decision-making, and communication, lays the groundwork for optimal outcomes in managing rheumatological manifestations of metabolic disorders. Healthcare teams can harness the collective expertise of endocrinologists, orthopedic specialists, and rheumatologists to navigate diagnostic complexities, devise tailored treatment plans, and ultimately enhance patient care quality.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bracewell C, Vila J, Narayanan K, Kelly C. Common ground: the overlap between Endocrinology and Rheumatology. European journal of internal medicine. 2009 Oct:20(6):569-71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.04.004. Epub 2009 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 19782915]

Merashli M, Chowdhury TA, Jawad AS. Musculoskeletal manifestations of diabetes mellitus. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2015 Nov:108(11):853-7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv106. Epub 2015 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 26025688]

Almoallim H, Cheikh M, Monjed A. Diabetes and Rheumatology. Skills in Rheumatology. 2021:(): [PubMed PMID: 36315795]

Fariduddin MM, Haq N, Bansal N. Hypothyroid Myopathy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137798]

Jadidi J, Sigari M, Efendizade A, Grigorian A, Lehto SA, Kolla S. Thyroid acropachy: A rare skeletal manifestation of autoimmune thyroid disease. Radiology case reports. 2019 Aug:14(8):917-919. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2019.04.021. Epub 2019 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 31193617]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceXu J, Wang B, Li Q, Yao Q, Jia X, Song R, Zhang JA. Risk of Thyroid Disorders in Patients with Gout and Hyperuricemia. Hormone and metabolic research = Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones et metabolisme. 2019 Aug:51(8):522-530. doi: 10.1055/a-0923-9184. Epub 2019 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 31408898]

Mittal M, Patra S, Saxena S, Roy A, Yadav T, Vedant D. Gout in Primary Hyperparathyroidism, Connecting Crystals to the Minerals. Journal of the Endocrine Society. 2022 Apr 1:6(4):bvac018. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvac018. Epub 2022 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 35261933]

Choi JH, Kim HR, Song KH. Musculoskeletal complications in patients with diabetes mellitus. The Korean journal of internal medicine. 2022 Nov:37(6):1099-1110. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2022.168. Epub 2022 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 36300322]

Westphal SG, Plumb T. Calciphylaxis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085562]

McDowell LA, Kudaravalli P, Chen RJ, Sticco KL. Iron Overload. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252387]

Harris A, Violand M. Charcot Neuropathic Osteoarthropathy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261935]

Zreik NH, Malik RA, Charalambous CP. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder and diabetes: a meta-analysis of prevalence. Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal. 2016 Jan-Mar:6(1):26-34. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2016.6.1.026. Epub 2016 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 27331029]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDimitri-Pinheiro S, Pimenta M, Cardoso-Marinho B, Torrão H, Soares R, Karantanas A. Diabetes: a silent player in musculoskeletal interventional radiology response. Porto biomedical journal. 2021 Jan-Feb:6(1):e112. doi: 10.1097/j.pbj.0000000000000112. Epub 2021 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 33532654]

Horton WB, Taylor JS, Ragland TJ, Subauste AR. Diabetic muscle infarction: a systematic review. BMJ open diabetes research & care. 2015:3(1):e000082. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000082. Epub 2015 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 25932331]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShah DN, Chorya HP, Ramesh NN, Gnanasekaram S, Patel N, Sethi Y, Kaka N. Myopathies of endocrine origin: A review for physicians. Disease-a-month : DM. 2024 Jan:70(1):101628. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2023.101628. Epub 2023 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 37718136]

Perini N, Santos RB, Romaldini JH, Villagelin D. THYROID ACROPACHY: A RARE MANIFESTATION OF GRAVES DISEASE IN JOINTS. AACE clinical case reports. 2019 Nov-Dec:5(6):e369-e371. doi: 10.4158/ACCR-2018-0591. Epub 2019 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 31967073]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGüneş E, Güneş M. Increased Prevalence of Autoimmune Rheumatologic Diseases in Patients With Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Cureus. 2023 Oct:15(10):e46906. doi: 10.7759/cureus.46906. Epub 2023 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 37841984]

Priesand S, Wyckoff J, Wrobel J, Schmidt B. Acute pseudogout of the foot following Parathyroidectomy: a case report. Clinical diabetes and endocrinology. 2017:3():10. doi: 10.1186/s40842-017-0048-x. Epub 2017 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 29177077]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNasr R, Ghazanfar H. Parathyroidectomy as a Cure for Calciphylaxis in a Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease Patient? The American journal of case reports. 2019 Aug 9:20():1170-1174. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.917105. Epub 2019 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 31395848]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAskari AD, Muir WA, Rosner IA, Moskowitz RW, McLaren GD, Braun WE. Arthritis of hemochromatosis. Clinical spectrum, relation to histocompatibility antigens, and effectiveness of early phlebotomy. The American journal of medicine. 1983 Dec:75(6):957-65 [PubMed PMID: 6650551]

Jena D, Barman A, Sahoo J, Baral D. Platelet-rich Plasma in the Treatment of Recurrent Flexor Tenosynovitis of Wrist Complicated with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in a Patient with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Case Report. Journal of orthopaedic case reports. 2022 Apr:12(4):97-100. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2022.v12.i04.2784. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36380999]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSavaş S, Köroğlu BK, Koyuncuoğlu HR, Uzar E, Celik H, Tamer NM. The effects of the diabetes related soft tissue hand lesions and the reduced hand strength on functional disability of hand in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2007 Jul:77(1):77-83 [PubMed PMID: 17141353]

Gerrits EG, Landman GW, Nijenhuis-Rosien L, Bilo HJ. Limited joint mobility syndrome in diabetes mellitus: A minireview. World journal of diabetes. 2015 Aug 10:6(9):1108-12. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i9.1108. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26265997]

Boro H, Bundela V, Jain V, Mannar V, Dalvi M. Diabetic Cheiroarthropathy in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Coeliac Disease. Cureus. 2022 Nov:14(11):e31708. doi: 10.7759/cureus.31708. Epub 2022 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 36561602]

Rai SK, Kashid M, Chakrabarty B, Upreti V, Shaki O. Is it necessary to screen patient with adhesive capsulitis of shoulder for diabetes mellitus? Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2019 Sep:8(9):2927-2932. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_244_19. Epub 2019 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 31681669]

Luo TD, Varacallo M. Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855792]

Dardari D. An overview of Charcot's neuroarthropathy. Journal of clinical & translational endocrinology. 2020 Dec:22():100239. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2020.100239. Epub 2020 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 33251117]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSevy JO, Sina RE, Varacallo M. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846321]

Morcuende JA, Dobbs MB, Crawford H, Buckwalter JA. Diabetic muscle infarction. The Iowa orthopaedic journal. 2000:20():65-74 [PubMed PMID: 10934627]

Gutch M, Sanjay S, Razi SM, Gupta KK. Thyroid acropachy: Frequently overlooked finding. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2014 Jul:18(4):590-1. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.137507. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25143927]

Bandeira F, Cusano NE, Silva BC, Cassibba S, Almeida CB, Machado VC, Bilezikian JP. Bone disease in primary hyperparathyroidism. Arquivos brasileiros de endocrinologia e metabologia. 2014 Jul:58(5):553-61 [PubMed PMID: 25166047]

Radford-Smith DE, Powell EE, Powell LW. Haemochromatosis: a clinical update for the practising physician. Internal medicine journal. 2018 May:48(5):509-516. doi: 10.1111/imj.13784. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29722188]

St Angelo JM, Taqi M, Fabiano SE. Adhesive Capsulitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422550]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZimmerman M, Gottsäter A, Dahlin LB. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Diabetes-A Comprehensive Review. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Mar 17:11(6):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11061674. Epub 2022 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 35329999]