Introduction

Prostate cancer is a disease of men. An estimated 1.2 million cases were diagnosed in 2018, making it the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in men worldwide. It was also the most common cancer in men aged over 55. In the same year, prostate cancer was the third most common cause of cancer-related death in men in North America and Europe. From a global perspective, deaths from liver, stomach, and esophageal cancer meant that it ranked sixth for cancer deaths internationally.[1]

The prostate is a small glandular organ (typically 20-30 g in the healthy adult male) responsible for producing most seminal fluid. It lies anterior to the rectum and encases the urethra between the bladder neck and the external urethral sphincter. The "nervi erigentes" (responsible for continence and erectile function) course from the hypogastric plexus and lie in intimate relation to its postero-lateral surfaces. These relationships are critical when considering the likely adverse events following any treatment for prostate cancer. The zonal anatomy of the prostate was described by McNeal in 1968 and remains in use today, with around 70% to 80% of cancers developing in the peripheral zone and cancer seldom found in the central zone.[2][3]

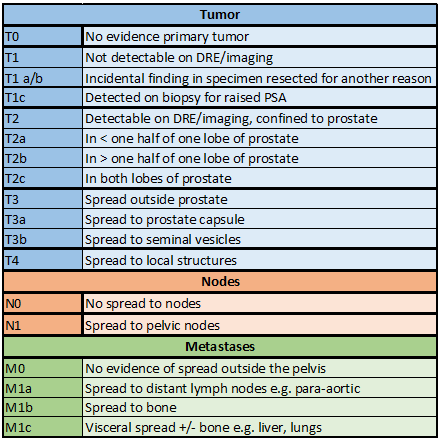

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) 2018 staging classification for prostate cancer is shown in the table (see Table. Localized Prostate Cancer Staging Guidelines, Tumor). Local invasion is to surrounding structures such as seminal vesicles, bladder, and rectum. Metastasis most commonly occurs via a lymphatic route to pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes and a hematogenous route to the bone. Visceral metastasis to the lung, liver, and other organs is relatively rare and associated with unusual pathology and a poor prognosis.[4][5]

In clinical practice, prostate cancer is most conveniently categorized as:

- Localized prostate cancer: T1/2/ early T3, N0, M0

- Locally advanced prostate cancer: Established T3 or T4, N0/1, M0

- Metastatic cancer: M1 disease

In this topic, localized prostate cancer includes cases of early T3 prostate cancer, either on the investigation (eg, transrectal ultrasound [TRUS], MRI) or on final pathology (eg, following radical prostatectomy).[6][7] The natural history of prostate cancer has been extensively studied in patients treated conservatively. Most localized prostate cancer represents an indolent disease, with population studies indicating slow progression in the majority over many years.[8]

Men with low-grade tumors rarely die from prostate cancer. They are much more likely to die from other causes first. On the other hand, men with high-grade disease are more likely to die from prostate cancer within ten years without radical treatment. The prognosis of men with intermediate-risk cancer is the most difficult to predict. The perceived increased risk of mortality compared to low-risk disease can often push clinicians towards radical treatment in these cases. Still, such a strategy has been challenged by the findings of studies such as the ProtecT study of treatments for localized prostate cancer. Prognostic markers and scoring will likely be of great interest to this group of patients.[8]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The most significant risk factors for prostate cancer are not modifiable; these include:

Age

Prostate cancer is rare under the age of 50 (1 in 350); the incidence steeply increases to 1 in 52 by age 59, and at age 65, the incidence is greater than 1 in 2, although many men will not be aware they have the disease. In the modern era of widespread serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, the majority of men have localized disease at diagnosis with a mean age of 66.[1][9][1]

Race

Worldwide, African-American men are the most likely racial group to develop prostate cancer and are also more likely to develop the disease at a younger age, with high rates evident in Afro-Caribbean men and those of West African origin. Hispanics are at lower risk than Caucasians, as are those from South-East Asia.[1] The reasons for these differences are unclear but appear to reflect genetic predisposition and environmental factors, including diet.

Family History

Although a minority of cases of prostate cancer are truly hereditary, a family history of prostate cancer increases the risk. The relative risk if a first-degree relative is affected is a 2-fold increase, with the risk increased around 8-fold if 2 or more first-degree relatives are affected.[6][10][6]

Other risk factors responsible for a minority of cases include inheritable gene mutations (eg, BRCA2 and HOXB13) and anthropometry; taller men are at a higher risk. No consistent link has been found between the incidence of prostate cancer and dietary factors, although obesity does represent a risk factor for progressive or advanced disease.[11][12]

Epidemiology

Prostate cancer is currently the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in men worldwide. It is an age-related disease, and the incidence is expected to rise alongside global life expectancy. The highest risk group for prostate cancer globally is African Americans living in the United States. The lowest risk group is Asian men living in their native country.[1][13]

Both incidence and mortality of prostate cancer vary vastly across the globe, and, as well as individual risk factors, much of this variation has been attributed to differences in asymptomatic disease screening patterns. For example, in a low-income area such as Western Africa, the age-standardized incidence rate is relatively low at 31.9 per 100,000, but the associated mortality rate is high at 18.6 per 100,000. In contrast, in a high-income area such as North America, the age-standardized incidence is much higher at 73.7 per 100,000, but the associated mortality rate is relatively low at 7.7 per 100,000. High detection rates for localized disease typically occur in high-income countries, likely due to PSA testing detecting earlier diseases with the associated reduction in mortality from treating the lower-risk disease and access to higher diagnostic and treatment capabilities.[13]

There have also been large variations in prostate cancer incidence worldwide over the past 30 years, further supporting the role of PSA screening in driving incidence data. Between 1986 and 1992, prostate cancer incidence doubled in the United States. This coincides with the initiation of widespread PSA screening. This spike was also seen in Europe and Australia. Incidence has started to fall, partially due to the loss of screening popularity due to over-diagnosis. In parallel, prostate cancer mortality, which had been falling over the previous two decades, has recently risen marginally. The recent US Preventative Services Task Force (PSTF) guidelines have clarified the position on PSA screening for men.[14][15]

Pathophysiology

The prostate consists of epithelial acini in a fibromuscular stroma. Almost all adult cases of prostate cancer are adenocarcinoma arising from the acinar epithelium. Rarer variants such as ductal adenocarcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, squamous neoplasms, basal cell carcinomata, and neuroendocrine tumors (World Health Organization [WHO] classification 2016) do occur and generally have a worse prognosis. Rarely, non-epithelial malignant transformation results in lymphomas and sarcomas, more commonly following radiation exposure for previous, eg, rectal cancer.[3]

Histopathology

Histological examination of a prostate needle biopsy currently represents the gold standard in establishing a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer. The diagnosis is most commonly based on microscopic criteria such as glandular architecture (infiltrative growth pattern), perineural invasion, prominent nucleoli, and absence of a defined basal cell layer on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides.

Biopsy interpretation can be challenging; immunohistochemistry to specific basal cell proteins in equivocal cases can differentiate benign from malignant tissue. Although these stains (eg, p63, cytokeratin 5/6, keratin 903) can help establish a diagnosis of cancer, there may also be a disrupted basal cell layer in some benign small glands. In these situations, a cancer diagnosis is based on morphology and confirmed by positivity for a-methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR) cytoplasmic staining. AMACR is expressed by approximately 80% of prostatic adenocarcinoma on needle biopsy.[5]

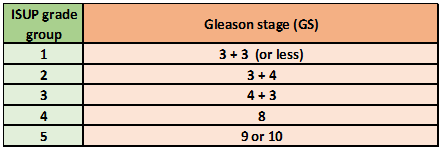

Grading is assigned by the Gleason system, which was introduced in 1966 and updated in 2005 and 2014 (see Table. Localized Prostate Cancer Staging Guidelines, Gleason Grade). Gleason grade is based on growth patterns ranging from 1 to 5. In practice, Gleason grades 1 and 2 are not usually described, and grade 3 (infiltrative growth pattern) represents the modern entry criterion for a diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Several grades often coexist in a single biopsy core or separate biopsy cores. In most cases, the Gleason score (GS) is the sum of the most common (primary) and the second most common (secondary) grade patterns. If a pattern 4 or 5 forms more than 95% of a specimen, any lower grade pattern representing less than 5% is ignored (eg, 97% of pattern 4 and 3% of pattern 3 is Gleason [4 + 4] rather than [4 + 3]). If any amount of pattern 4 or 5 is seen within a specimen, it is included in the GS, even if it forms the tertiary pattern.

For practical purposes, Gleason 6 (3 + 3) is the lowest score usually seen, and patients should be counseled that a grade of 6/10 is considered a low grade. Most recently, the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) has recommended that Gleason scores less than or equal to 6, 3 + 4 = 7, 4 + 3 = 7, 8, and 9-10 be reported as 5 Gleason group grades, ie, ISUP groups 1 to 5 respectively. This system provides additional prognostic benefit by separating Gleason score 7 diseases into 3 + 4 (Group 2) and 4 + 3 (higher risk Group 3).[16][17]

History and Physical

Localized prostate cancer typically causes no symptoms. Any lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are usually due to associated benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Over half of men over the age of 50 will experience LUTS related to BPH. Other causes of symptoms include prostatitis, UTI, urethral stricture, and overactive bladder. This can result in an incidental diagnosis of early-stage cancer with an uncertain impact on long-term mortality. Prostate cancer can present with new-onset erectile dysfunction or rarely with hemoejaculate or initial hematuria.[18]

Symptoms that might prompt investigation for prostate cancer include:

- Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as hesitancy, postmicturition dribbling, and poor stream

- Hematuria

- Hemoejaculate

- New-onset erectile dysfunction

Evaluation

Evaluation for localized prostate cancer most commonly involves a serum PSA level, digital rectal examination (DRE), multiparametric MRI (mpMRI), and needle prostate biopsy. It is relatively rare nowadays for localized prostate cancer to be diagnosed incidentally during treatment for BPH (eg, transurethral resection chippings) and an investigation for other symptoms (eg, as a hot spot in the prostate on PET scanning). Approximately 10% of prostates removed during a cystoprostatectomy for high-grade bladder urothelial cancer will have foci of prostate cancer that will precipitate further investigation. PSA) testing is widely carried out in the context of case-finding for prostate cancer yet remains highly controversial as a screening modality.

There is strong evidence showing that PSA screening increases the detection of prostate cancer, in particular localized disease, by approximately 30%. Despite this, meta-analyses of the international data have demonstrated no apparent impact on overall survival.[19]

Diagnosis of cases that are unlikely to progress in a man's lifetime to significant clinical illness has been termed "over-diagnosis." The rationale is that treatment of the condition will not benefit the man and, therefore, represents overtreatment of a screen-detected condition. The process of diagnosis (eg, biopsy) has appreciable morbidity and, indeed, mortality, and all conventional treatments for prostate cancer have adverse events that hurt the quality of life.[6][20][6][21][22][23]

These risk-benefit considerations have led to recommendations against routine PSA testing in the US and Europe. The current American Cancer Society Guidelines for targeted prostate cancer screening are as follows:

PSA +/- DRE is offered to the following groups of patients only after providing information on the risks, benefits, and uncertainties of prostate cancer screening and if they have a life expectancy greater than 10 years:

- Men aged ≥50

- Men aged ≥45 with a high risk of prostate cancer (African-American or father/brother diagnosed before age 65)

- Men aged ≥40 with significantly higher risk (multiple relatives diagnosed before age 65)

The PSA threshold for further investigation varies between 3.0 (Europe) and 4.0 (US). PSA levels are influenced by sexual activity, prostatic manipulation, UTI, BPH, and vigorous exercise, in addition to PSA protein instability and assay characteristics. Men with a borderline PSA result are commonly offered a repeat PSA level a few weeks later with advice to avoid sexual activity and vigorous exercise for 48 to 72 hours before the repeat test.[6][24][25][26]

Patients are commonly offered DRE alongside PSA testing. A suspicious DRE alone, even in the context of a low PSA, should prompt further investigation, as approximately 20% of localized cancers occur without an elevated PSA level.

Following PSA and DRE, multiparametric MRI scanning (mpMRI) or biparametric MRI is offered. MpMRI combines anatomical and functional information using T1- and T2-weighted sequences, dynamic contrast enhancement (DCE), and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). An experienced urological radiologist scores the subsequent images using, for example, the Likert or PI-RADS system.

Likert can be used in detection, active surveillance, post-treatment, and reoccurrence. It utilizes non-pre-specified imaging features and relies on user experience to be interpreted well. PI-RADS can be used in detection only. It utilizes pre-specified imaging features and is less dependent on reader experience. Likert may be more accurate when used by experienced urological radiologists. Both systems produce a score between 1 and 5, with a higher score indicating a higher likelihood of cancer being detected on biopsy. In most centers, a score of greater than or equal to 3 will prompt a biopsy. In men with more than 1 risk factor (eg, strong family history and high PSA density), a systematic biopsy might be recommended with a "normal" MRI scan.

Before mpMRI, many men underwent unnecessary biopsies as they had a clinically insignificant disease. The introduction of mpMRI as an initial investigation can potentially avoid biopsy in 25% of men with an elevated PSA at the risk of missing approximately 3% to 5% of cases.[22][27][28][29][30][22]

For definitive prostate cancer diagnosis, a positive needle biopsy, typically using an 18-G needle, is carried out, most commonly under local anesthetic. Different strategies for biopsy, as well as different targeting modalities, can be used. A targetted biopsy can be obtained using real-time in-bore biopsy during the MRI scan. More commonly, cognitive or fusion targetting using the saved MRI image with the real-time transrectal ultrasound image is employed, with the needle deployed either transrectally or transperineally. A TRUS-guided biopsy remains the most common technique, but transperineal (TP) biopsy is growing in popularity, with usage varying across centers. The advantages of TP biopsy include a lower post-biopsy sepsis rate and the ability to sample tissue within the anterior of the prostate gland, which is often missed by TRUS biopsy. The disadvantages include increased discomfort and analgesic requirements, increased urinary retention rates, and a higher risk of post-biopsy erectile dysfunction. Compared with TRUS, there is no difference in the incidence of hematuria, hemoejaculate, or 30-day mortality with TP biopsies. There is a paucity of high-quality evidence for the global adoption of TP sampling in Europe or America.

Systematic sampling, taking a minimum of 10 cores (usually 10-12) from representative areas of the peripheral zones of the prostate, in addition to targetted sampling, results in a higher yield of significant prostate cancer. There is, however, a higher risk of detecting incidental non-clinically significant disease. Patients undergoing biopsy should receive prophylactic antibiotics. It is important for patients to be warned about the risks above, including the most usual postprocedural hemoejaculate (>90%), hematuria (>80%), and rectal bleeding (>20%), usually lasting for 1 to 2 days, but can be prolonged for 1 to 2 weeks, particularly blood in the semen which can often take many weeks to clear.[6][31][32][6]

Following the biopsy, prostate cancer is risk-stratified to determine the necessity for further investigations and decide on initial management. This includes PSA, grade group (table 2), and stage:

- Low risk: PSA less than 10 ng/ml and stage T1-T2a and grade group 1

- High risk: PSA less than 20 or grade group 4-5

- Intermediate risk: constitutes a variety of combinations falling between low and high risk

All patients with high-risk cancer should complete staging examinations looking for metastatic disease with a bone scan and cross-sectional abdominopelvic imaging.[6][33][34] The routine use of such imaging in intermediate-risk is controversial.

Treatment / Management

Localized prostate cancer represents a paradox in that when left untreated, it is generally associated with a good prognosis. However, because prostate cancer is a common cause of cancer-related mortality, there is usually significant patient anxiety once the diagnosis is confirmed. All standard treatments carry risks of adverse events that might negatively impact short-, medium-, or long-term quality of life. As such, the clinical approach to managing localized prostate cancer must take into account not only the disease features, such as stage, grade, and volume of cancer detected, but also patient co-morbidities, life expectancy, and priorities.

The optimal management of localized prostate cancer starts with discussion by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) consisting of radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, urologists, histopathologists, radiologists, and specialist nurses. Each brings their expertise and knowledge of the patient to help determine which treatment options are appropriate for an individual.

There is evidence that a shared decision-making (SDM) environment leads to better self-perceived quality of life and less treatment regret for patients with prostate cancer. However, the impact on long-term oncological outcomes is uncertain. SDM is a process whereby clinicians help patients reach evidence-informed and value-congruent medical decisions collaboratively. SDM takes time and relies on physician empathy and excellent communication skills. The role of the physician is to draw attention to the natural history of prostate cancer as a slow-growing cancer to reduce anxiety. It is important to reassure the patient that discussing the pros and cons of the various approaches is well-spent.[35] (A1)

The standard approaches to localized prostate cancer include a monitoring strategy, radical surgery, radiation therapy (brachytherapy or external beam), and emergent focal therapies.[6]

Monitoring

Natural history studies suggest that the majority of men, particularly elderly men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer, die with their disease rather than of it, reflecting competing hazards associated with aging. Although many cases do not progress, there does appear to be a true progression rate over the years of follow-up. Both grade and volume of the disease are predictive of progression to locally advanced and metastatic disease. As such, monitoring strategies are most suited to elderly men, low-risk diseases, or selected intermediate-risk diseases with careful counseling and close follow-up. Two broad approaches to monitoring are generally described.

Conservative Palliative Strategy

Often termed "watchful waiting," this modality is most commonly offered to elderly, frail, asymptomatic men. It is anticipated that disease progression in the remaining lifetime of the man is unlikely to cause a clinically significant problem. In addition, the morbidity/ mortality associated with radical treatment does not justify the anticipated benefits of longevity. Treatment in the form of primary androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) may be offered to control symptoms as and when they occur or if there is evidence of metastatic disease. The aim is remission, which occurs in around 80% of cases, rather than "cure." This approach has been called into question due to improvements in life expectancy, treatments, and imaging modalities. Additionally, evidence demonstrates significantly improved survival when radiotherapy is added to ADT for patients who previously would have received ADT alone.[36](B2)

Deferred Curative Strategy

Often termed "active surveillance," this approach is aimed at reducing overtreatment for prostate cancer that is unlikely to progress in the man’s lifetime. Regular follow-up using a combination of biomarker repeat assessment (typically serum PSA), imaging findings (interval and mp-MRI), clinical evaluation (symptoms/DRE), and repeat biopsy are offered. A commonly used protocol (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] guidance, UK) is:

- First-year: PSA test every 3 to 4 months

- At 6 and 12 months: Clinical review, DRE

- 12 months: Interval mpMRI

- Subsequently: Six monthly PSA with yearly DRE in subsequent years

Repeat biopsy is utilized where there are discordant findings between biomarkers and imaging. Radical treatment is offered if evidence of disease progression is present or if the patient requests it. Large randomized controlled trials, such as the ProtecT trial, have demonstrated no detriment to 10-year survival from offering active surveillance over primary radical treatment. The trade-off for the patient is an increased risk of disease progression against the adverse effects of radical treatment.[6][37][38](A1)

Recent evidence has demonstrated survival benefits from radiotherapy plus ADT in men who would have been traditionally assigned to watchful waiting when they progress to locally advanced disease. This calls into question the distinction between active surveillance and watchful waiting. For instance, although the risk-benefit analysis at initial presentation with the localized disease might be considered unfavorable in an asymptomatic man with co-morbidities, progression to a more advanced stage (eg, T3 disease from T2) could trigger a more radical approach. This is in line with deferred curative treatment. As such, the key to successful monitoring of localized prostate cancer rests on thorough clinical evaluation and an honest appraisal, with the patient, of goals and priorities.[39](A1)

Surgical Management

Radical prostatectomy can be open (ORP), laparoscopic (LRP), or robotic-assisted (RARP). ORP is the traditional method, while LRP and RARP are increasingly popular. As RARP becomes more available, conventional LRP has been overtaken. Patients with high-risk cancer should also undergo extended pelvic lymph node dissection. Nerve-sparing RP reduces the risk of subsequent urinary and sexual dysfunction. The risk of post-RP incontinence increases with age, with 75 years being the most common cut-off in most centers. There is currently a lack of evidence demonstrating the superiority of any specific method of RP for mortality, cancer recurrence, or postoperative complications. However, LRP and RARP will likely lead to shorter hospital stays and fewer blood transfusions.[6][40](A1)

Radiation Therapy

External-beam Radiation Therapy

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is the preferred method for external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) delivery as it allows targeted radiation delivery to the prostate gland with less toxicity to surrounding organs. Side effects of radiotherapy are gastrointestinal toxicity, genitourinary toxicity, and secondary malignancy. Acute proctitis and cystitis commonly resolve following treatment completion.

Hypofractionation (>2 Gy/day) reduces treatment time and improves resource utilization without compromising tumor control, reoccurrence, and side effects when compared to traditional fractions (1.8-2 Gy/day). Hypofractionated IMRT is commonly 60Gy delivered in 20 fractions.

Androgen deprivation therapy is commonly used as an adjunct to EBRT in intermediate and high-risk prostate cancer. In localized prostate cancer, this is generally short-term (6 months). In high-risk patients, particularly where there might be early T3 extension, ADT might be prolonged for up to 3 years. The safety of such neoadjuvant use of ADT has recently been questioned as there is evidence of significant cardiovascular side effects. The current trend is to aim to reduce the duration of exposure to ADT to as short a period as possible and, indeed, avoid it altogether in men at particularly high risk of cardiovascular adverse effects. The impact of these changes on oncological outcomes has not been thoroughly explored.[6][41][42][43][6](A1)

Brachytherapy

This is the implantation of radioactive seeds into the prostate. It is used for primary treatment in low-risk and low-volume intermediate-risk localized prostate cancer. It can also be used as an adjuvant to EBRT in high-volume intermediate-risk and high-risk cancer.

Brachytherapy can be divided into low dose rate (LDR) and high dose rate (HDR). In LDR brachytherapy, radioactive seeds release their radiation over a few months and remain in the prostate permanently. In HDR, a radioactive source is delivered into the prostate during a single visit to the hospital and then removed; this is then most commonly combined with a subsequent course of external beam radiotherapy (brachytherapy boost).

Brachytherapy commonly causes urinary side effects such as urinary retention, incontinence, and the requirement for transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). It also causes erectile dysfunction in up to 40% of patients.[6][44][45](B3)

Emergent Focal Therapies

Radical treatment for prostate cancer is associated with significant detriment to the quality of life, for example, incontinence, reduced sexual function, and radiation toxicity. Increased sophistication of prostate imaging has allowed for the rapid emergence of focal therapies such as focal laser ablation, high-intensity focal ultrasound (HIFU), irreversible electroporation (IRE), photodynamic therapy (VTP), and focal cryotherapy. These are used to ablate the dominant tumor in the prostate to achieve tumor control while reducing the adverse events of treatment. Of these, cryotherapy and HIFU are probably the most available.

As yet, studies for these treatments are confined to short and intermediate-term follow-up. They appear to have a vastly lower rate of high-grade complications. However, the long-term oncological results are uncertain, particularly given a relatively high rate of residual or recurrent cancer on repeat biopsy. At present, as promising as the results appear from the perspective of preserving the quality of life, they should only be offered as part of a clinical trial.[46](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for localized prostate cancer are mainly conditions that produce LUTS, including:

- BPH

- Prostatitis

- Urethral stricture

- UTI

- Overactive bladder

- Bladder cancer

- Advanced prostate cancer

Prognosis

Despite being common, prostate cancer has the highest 5-year survival of all cancers at 98%. As previously discussed, localized prostate cancer is frequently indolent and has an excellent prognosis even if left untreated. By definition, patients with high-grade, high-volume cancer are more likely to progress to locally advanced and metastatic disease, but risks can be mitigated by early detection and treatment.

Evidence demonstrates similar outcomes for patients treated with active surveillance, surgery, and radiotherapy, although patient wishes and side effect profiles should be considered. Patients choosing monitoring strategies should be aware of a small increase in the risk of progression and that subsequent radical treatment will be required in around 50% of cases, as often for patient anxiety as for biochemical, clinical, or imaging evidence of disease progression.[22][47]

Complications

Complications of localized prostate cancer mainly consist of side effects of treatment. For surgical treatment, this is nerve damage resulting in incontinence or erectile dysfunction. Surgery also involves risks, such as anesthetic risk and blood loss. Radiotherapy risks include GI, GU, local toxicity, and the risk of future secondary malignancies.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The majority of risk factors for prostate cancer are not modifiable. As such, patients should be educated about inherent risk factors such as age, ethnicity, and family history to ensure the correct groups are present for PSA testing. It is important to educate patients requesting PSA screening about the risks of over-diagnosis and to reassure those who do not meet the criteria for testing.

Lifestyle factors do not affect the risk of developing prostate cancer but may influence the risk of progression. Patients already diagnosed with prostate cancer should be encouraged to lead a healthy lifestyle, including diet and exercise, to reduce the risk of developing advanced disease. Obesity is a risk factor for prostate cancer progression and advanced disease.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Localized prostate cancer is commonly an indolent disease. Patients exhibit few to no symptoms; if symptoms are present, they are often caused by co-existing BPH. It is important to know the criteria for offering a PSA test and be prepared to discuss the pros and cons of such testing with patients. The steps involved in assessing a patient with localized prostate cancer are key to selecting the best treatment strategy for that patient, be it active or passive.

The initial evaluation of lower urinary tract symptoms and any request for PSA testing usually rests with the family physician or general practitioner. At this point, the symptoms are carefully evaluated, other conditions that might mimic BPH (eg, bladder cancer) are searched for, and patient counseling around the pros and cons of PSA testing is carried out.

The urologist is usually the primary specialist involved in making the diagnosis and, therefore, the first line of providing care for men with localized prostate cancer. Given the many treatment options involved and the difficulties associated with the interpretation of needle biopsy and MRI scans of the prostate, the involvement of other multidisciplinary team members is essential before a definitive treatment discussion. Initial referral is commonly from the general practitioner. Diagnosis involves histology and radiology, while treatment may involve a radiation oncologist or a full surgical team, including recovery and ward teams.

Clinical nurse specialists are invaluable in supporting patients diagnosed with cancer, and input from psychologists or support groups might prove valuable. Trained clinical exercise specialists can help achieve lifestyle changes, including exercise training and dietary modification.

When considering treatment, large randomized controlled trials have demonstrated equivalent overall and disease-specific mortality of active surveillance, radical radiotherapy, and radical surgery at 10 years of follow-up. Thus, it is important to assess each patient individually to establish his co-morbidities and priorities to optimize treatment and minimize side effects (for example, not offering radiotherapy to a patient with pre-existing colitis).

With prompt and effective diagnosis and treatment, localized prostate cancer has a favorable prognosis for patients. Multidisciplinary team members must support patients and optimize oncological and nononcological outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rawla P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World journal of oncology. 2019 Apr:10(2):63-89. doi: 10.14740/wjon1191. Epub 2019 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 31068988]

Selman SH. The McNeal prostate: a review. Urology. 2011 Dec:78(6):1224-8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.07.1395. Epub 2011 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 21908026]

Packer JR, Maitland NJ. The molecular and cellular origin of human prostate cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2016 Jun:1863(6 Pt A):1238-60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.02.016. Epub 2016 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 26921821]

Leslie SW, Soon-Sutton TL, R I A, Sajjad H, Skelton WP. Prostate Cancer. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261872]

Humphrey PA. Histopathology of Prostate Cancer. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2017 Oct 3:7(10):. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a030411. Epub 2017 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 28389514]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Briers E, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, Fossati N, Gross T, Henry AM, Joniau S, Lam TB, Mason MD, Matveev VB, Moldovan PC, van den Bergh RCN, Van den Broeck T, van der Poel HG, van der Kwast TH, Rouvière O, Schoots IG, Wiegel T, Cornford P. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. European urology. 2017 Apr:71(4):618-629. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.003. Epub 2016 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 27568654]

Fine SW. Evolution in Prostate Cancer Staging: Pathology Updates From AJCC 8th Edition and Opportunities That Remain. Advances in anatomic pathology. 2018 Sep:25(5):327-332. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000200. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29870405]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlbertsen PC, Hanley JA, Fine J. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2005 May 4:293(17):2095-101 [PubMed PMID: 15870412]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBernstein AN, Shoag JE, Golan R, Halpern JA, Schaeffer EM, Hsu WC, Nguyen PL, Sedrakyan A, Chen RC, Eggener SE, Hu JC. Contemporary Incidence and Outcomes of Prostate Cancer Lymph Node Metastases. The Journal of urology. 2018 Jun:199(6):1510-1517. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.12.048. Epub 2017 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 29288121]

Barry MJ, Simmons LH. Prevention of Prostate Cancer Morbidity and Mortality: Primary Prevention and Early Detection. The Medical clinics of North America. 2017 Jul:101(4):787-806. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.03.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28577627]

Vinceti M, Filippini T, Del Giovane C, Dennert G, Zwahlen M, Brinkman M, Zeegers MP, Horneber M, D'Amico R, Crespi CM. Selenium for preventing cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Jan 29:1(1):CD005195. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005195.pub4. Epub 2018 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 29376219]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarkozannes G, Tzoulaki I, Karli D, Evangelou E, Ntzani E, Gunter MJ, Norat T, Ioannidis JP, Tsilidis KK. Diet, body size, physical activity and risk of prostate cancer: An umbrella review of the evidence. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2016 Dec:69():61-69. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.09.026. Epub 2016 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 27816833]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePernar CH, Ebot EM, Wilson KM, Mucci LA. The Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2018 Dec 3:8(12):. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a030361. Epub 2018 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 29311132]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWelch HG, Albertsen PC. Reconsidering Prostate Cancer Mortality - The Future of PSA Screening. The New England journal of medicine. 2020 Apr 16:382(16):1557-1563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1914228. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32294352]

US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, Bibbins-Domingo K, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Ebell M, Epling JW Jr, Kemper AR, Krist AH, Kubik M, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Siu AL, Tseng CW. Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018 May 8:319(18):1901-1913. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3710. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29801017]

Epstein JI. An update of the Gleason grading system. The Journal of urology. 2010 Feb:183(2):433-40. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.10.046. Epub 2009 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 20006878]

Egevad L, Delahunt B, Srigley JR, Samaratunga H. International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grading of prostate cancer - An ISUP consensus on contemporary grading. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 2016 Jun:124(6):433-5. doi: 10.1111/apm.12533. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27150257]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMerriel SWD, Funston G, Hamilton W. Prostate Cancer in Primary Care. Advances in therapy. 2018 Sep:35(9):1285-1294. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0766-1. Epub 2018 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 30097885]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIlic D, Djulbegovic M, Jung JH, Hwang EC, Zhou Q, Cleves A, Agoritsas T, Dahm P. Prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2018 Sep 5:362():k3519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3519. Epub 2018 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 30185521]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCarroll PH, Mohler JL. NCCN Guidelines Updates: Prostate Cancer and Prostate Cancer Early Detection. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2018 May:16(5S):620-623. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0036. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29784740]

Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Zappa M, Nelen V, Kwiatkowski M, Lujan M, Määttänen L, Lilja H, Denis LJ, Recker F, Paez A, Bangma CH, Carlsson S, Puliti D, Villers A, Rebillard X, Hakama M, Stenman UH, Kujala P, Taari K, Aus G, Huber A, van der Kwast TH, van Schaik RH, de Koning HJ, Moss SM, Auvinen A, ERSPC Investigators. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet (London, England). 2014 Dec 6:384(9959):2027-35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. Epub 2014 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 25108889]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, Mason M, Metcalfe C, Holding P, Wade J, Noble S, Garfield K, Young G, Davis M, Peters TJ, Turner EL, Martin RM, Oxley J, Robinson M, Staffurth J, Walsh E, Blazeby J, Bryant R, Bollina P, Catto J, Doble A, Doherty A, Gillatt D, Gnanapragasam V, Hughes O, Kockelbergh R, Kynaston H, Paul A, Paez E, Powell P, Prescott S, Rosario D, Rowe E, Neal D. Active monitoring, radical prostatectomy and radical radiotherapy in PSA-detected clinically localised prostate cancer: the ProtecT three-arm RCT. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2020 Aug:24(37):1-176. doi: 10.3310/hta24370. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32773013]

Loeb S, Vellekoop A, Ahmed HU, Catto J, Emberton M, Nam R, Rosario DJ, Scattoni V, Lotan Y. Systematic review of complications of prostate biopsy. European urology. 2013 Dec:64(6):876-92. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.05.049. Epub 2013 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 23787356]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSmith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Fedewa SA, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D, Wender RC. Cancer screening in the United States, 2019: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2019 May:69(3):184-210. doi: 10.3322/caac.21557. Epub 2019 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 30875085]

Carroll PR, Parsons JK, Andriole G, Bahnson RR, Castle EP, Catalona WJ, Dahl DM, Davis JW, Epstein JI, Etzioni RB, Farrington T, Hemstreet GP 3rd, Kawachi MH, Kim S, Lange PH, Loughlin KR, Lowrance W, Maroni P, Mohler J, Morgan TM, Moses KA, Nadler RB, Poch M, Scales C, Shaneyfelt TM, Smaldone MC, Sonn G, Sprenkle P, Vickers AJ, Wake R, Shead DA, Freedman-Cass DA. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Prostate Cancer Early Detection, Version 2.2016. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2016 May:14(5):509-19 [PubMed PMID: 27160230]

Heijnsdijk EAM, Bangma CH, Borràs JM, de Carvalho TM, Castells X, Eklund M, Espinàs JA, Graefen M, Grönberg H, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Leeuwen PJV, Nelen V, Recker F, Roobol MJ, Vandenbulcke P, de Koning HJ. Summary statement on screening for prostate cancer in Europe. International journal of cancer. 2018 Feb 15:142(4):741-746. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31102. Epub 2017 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 29023685]

Puech P, Sufana Iancu A, Renard B, Villers A, Lemaitre L. Detecting prostate cancer with MRI - why and how. Diagnostic and interventional imaging. 2012 Apr:93(4):268-78. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2012.01.019. Epub 2012 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 22465788]

Khoo CC, Eldred-Evans D, Peters M, Bertoncelli Tanaka M, Noureldin M, Miah S, Shah T, Connor MJ, Reddy D, Clark M, Lakhani A, Rockall A, Hosking-Jervis F, Cullen E, Arya M, Hrouda D, Qazi H, Winkler M, Tam H, Ahmed HU. Likert vs PI-RADS v2: a comparison of two radiological scoring systems for detection of clinically significant prostate cancer. BJU international. 2020 Jan:125(1):49-55. doi: 10.1111/bju.14916. Epub 2019 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 31599113]

Ahmed HU, El-Shater Bosaily A, Brown LC, Gabe R, Kaplan R, Parmar MK, Collaco-Moraes Y, Ward K, Hindley RG, Freeman A, Kirkham AP, Oldroyd R, Parker C, Emberton M, PROMIS study group. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Feb 25:389(10071):815-822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32401-1. Epub 2017 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 28110982]

Faria R, Soares MO, Spackman E, Ahmed HU, Brown LC, Kaplan R, Emberton M, Sculpher MJ. Optimising the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer in the Era of Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Cost-effectiveness Analysis Based on the Prostate MR Imaging Study (PROMIS). European urology. 2018 Jan:73(1):23-30. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.08.018. Epub 2017 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 28935163]

Rosario DJ, Lane JA, Metcalfe C, Donovan JL, Doble A, Goodwin L, Davis M, Catto JW, Avery K, Neal DE, Hamdy FC. Short term outcomes of prostate biopsy in men tested for cancer by prostate specific antigen: prospective evaluation within ProtecT study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2012 Jan 9:344():d7894. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7894. Epub 2012 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 22232535]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBerry B, Parry MG, Sujenthiran A, Nossiter J, Cowling TE, Aggarwal A, Cathcart P, Payne H, van der Meulen J, Clarke N. Comparison of complications after transrectal and transperineal prostate biopsy: a national population-based study. BJU international. 2020 Jul:126(1):97-103. doi: 10.1111/bju.15039. Epub 2020 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 32124525]

Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E, Chen RC, Crispino T, Fontanarosa J, Freedland SJ, Greene K, Klotz LH, Makarov DV, Nelson JB, Rodrigues G, Sandler HM, Taplin ME, Treadwell JR. Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline. Part I: Risk Stratification, Shared Decision Making, and Care Options. The Journal of urology. 2018 Mar:199(3):683-690. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095. Epub 2017 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 29203269]

D'Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, Schultz D, Blank K, Broderick GA, Tomaszewski JE, Renshaw AA, Kaplan I, Beard CJ, Wein A. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998 Sep 16:280(11):969-74 [PubMed PMID: 9749478]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMartínez-González NA, Plate A, Markun S, Senn O, Rosemann T, Neuner-Jehle S. Shared decision making for men facing prostate cancer treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Patient preference and adherence. 2019:13():1153-1174. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S202034. Epub 2019 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 31413545]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrundage M, Sydes MR, Parulekar WR, Warde P, Cowan R, Bezjak A, Kirkbride P, Parliament M, Moynihan C, Bahary JP, Parmar MK, Sanders K, Chen BE, Mason MD. Impact of Radiotherapy When Added to Androgen-Deprivation Therapy for Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer: Long-Term Quality-of-Life Outcomes From the NCIC CTG PR3/MRC PR07 Randomized Trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015 Jul 1:33(19):2151-7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.8724. Epub 2015 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 26014295]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, Mason M, Metcalfe C, Holding P, Davis M, Peters TJ, Turner EL, Martin RM, Oxley J, Robinson M, Staffurth J, Walsh E, Bollina P, Catto J, Doble A, Doherty A, Gillatt D, Kockelbergh R, Kynaston H, Paul A, Powell P, Prescott S, Rosario DJ, Rowe E, Neal DE, ProtecT Study Group. 10-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Oct 13:375(15):1415-1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220. Epub 2016 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 27626136]

Vernooij RW, Lancee M, Cleves A, Dahm P, Bangma CH, Aben KK. Radical prostatectomy versus deferred treatment for localised prostate cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2020 Jun 4:6(6):CD006590. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006590.pub3. Epub 2020 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 32495338]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWarde P, Mason M, Ding K, Kirkbride P, Brundage M, Cowan R, Gospodarowicz M, Sanders K, Kostashuk E, Swanson G, Barber J, Hiltz A, Parmar MK, Sathya J, Anderson J, Hayter C, Hetherington J, Sydes MR, Parulekar W, NCIC CTG PR.3/MRC UK PR07 investigators. Combined androgen deprivation therapy and radiation therapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2011 Dec 17:378(9809):2104-11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61095-7. Epub 2011 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 22056152]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceIlic D, Evans SM, Allan CA, Jung JH, Murphy D, Frydenberg M. Laparoscopic and robotic-assisted versus open radical prostatectomy for the treatment of localised prostate cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Sep 12:9(9):CD009625. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009625.pub2. Epub 2017 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 28895658]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZiehr DR, Chen MH, Zhang D, Braccioforte MH, Moran BJ, Mahal BA, Hyatt AS, Basaria SS, Beard CJ, Beckman JA, Choueiri TK, D'Amico AV, Hoffman KE, Hu JC, Martin NE, Sweeney CJ, Trinh QD, Nguyen PL. Association of androgen-deprivation therapy with excess cardiac-specific mortality in men with prostate cancer. BJU international. 2015 Sep:116(3):358-65. doi: 10.1111/bju.12905. Epub 2014 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 25124891]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHickey BE, James ML, Daly T, Soh FY, Jeffery M. Hypofractionation for clinically localized prostate cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2019 Sep 3:9(9):CD011462. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011462.pub2. Epub 2019 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 31476800]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWeg ES, Pei X, Kollmeier MA, McBride SM, Zelefsky MJ. Dose-Escalated Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer: 15-Year Outcomes Data. Advances in radiation oncology. 2019 Jul-Sep:4(3):492-499. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2019.03.012. Epub 2019 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 31360805]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDutta SW, Alonso CE, Libby B, Showalter TN. Prostate cancer high dose-rate brachytherapy: review of evidence and current perspectives. Expert review of medical devices. 2018 Jan:15(1):71-79. doi: 10.1080/17434440.2018.1419058. Epub 2017 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 29251165]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZaorsky NG, Davis BJ, Nguyen PL, Showalter TN, Hoskin PJ, Yoshioka Y, Morton GC, Horwitz EM. The evolution of brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Nature reviews. Urology. 2017 Jun 30:14(7):415-439. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.76. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28664931]

Ahdoot M, Lebastchi AH, Turkbey B, Wood B, Pinto PA. Contemporary treatments in prostate cancer focal therapy. Current opinion in oncology. 2019 May:31(3):200-206. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000515. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30865133]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSiegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2019 Jan:69(1):7-34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. Epub 2019 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 30620402]