Introduction

Microsporidia are an unusually large group of unique, eukaryotic, obligate, intracellular parasites that biologists have studied for more than 150 years. Microsporidia are well-adapted pathogens and important agricultural parasites that infect honeybees, silkworms, and other insects. The organism is also a parasite for fish, rodents, rabbits, primates, and humans. This article reviews Microsporidia with emphases on the latest biological discoveries.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Biologists have studied Microsporidia for more than 150 years. Microsporidia include 187 genera with approximately 1500 species. Microsporidia are ubiquitous in the environment; they have evolved in a unique and sophisticated manner so that they not only survive in the surrounding environment but are also able to live inside other cells.[1]

Classification of Microsporidia is based on microscopic morphology and ultrastructural spores characteristics. The host range in many cases is incongruent with the phylogenetic relationship that is further revealed by molecular methods through rRNA genetic sequencing which is currently used as the principle way of defining taxonomy.[2]

Epidemiology

Microsporidia in Animals

Infection with Microsporidia also known as microsporidiosis occurs worldwide. Infection occurs via commonly known pathogens in agriculture and leads to lost resources. The classic species include Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae that infect honeybees. Studies have shown that the mortality rate of honeybees infected with N. ceranae is nearly 94%, and infected populations usually die within 8 days. Three days post-infection, the observed mature spores inside host cells signal that the lifecycle of the parasite is complete. The parasite invades both the tip of folds and the basal cells of the bee’s epithelium, and the infection spreads between epithelial cells rapidly.[3]

Other examples of infection with microsporidia is Loma salmonae which infects salmon and Thelohania species which infects shrimp. Infection with Loma salmonae can induce systemic symptoms including significant changes in the gills. The parasite also infects the heart, spleen, kidney, and pseudo-branch of infected marine or freshwater fish.

Microsporidia in Humans

In humans, infection with this opportunistic pathogen was not highly recognized at the beginning of the century. In 1924, researchers first suggested that Microsporidia infected humans, and until 1985, only a few reports of human microsporidiosis were published. After this, Microsporidia became increasingly recognized worldwide as opportunistic infectious agents, and presently, Microsporidia are recognized as emerging organisms in many areas of both developed and developing countries.[4] Microsporidia are widely distributed worldwide among children, travelers, organ recipients, elderly, patients with malignant disease and diabetes, and HIV patients.[4] In developed countries, the occurrence of microsporidiosis in HIV patients has gradually decreased due to anti-retroviral therapy and better hygiene.

Among the nearly 1500 species described, only 17 are pathogenic to human, and some of them include Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Encephalitozoon, Anncaliia, Enterocytozoon, Tubulinosema, Microsporidium africanum, and Trachipleistophora hominis. In the majority of cases, E. bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis have been the 2 species detected most often in infected humans.[5]

In developed countries, the prevalence rates for Microsporidia infection in HIV-seropositive persons with diarrhea range from 2% to 78% varying by degree of immunosuppression and treatment. In HIV-seropositive persons without diarrhea, infections range from 1.4% to 4.3%.[6] In individuals not infected with HIV, the seroprevalence rates range from 1.3% to 22% among blood donors, pregnant women, slaughterhouse workers, and persons with unknown causes of diarrhea (possibly caused by Microsporidia infection).[7]

Pathophysiology

Clinical Manifestation

The clinical manifestation of microsporidia infection ranges from asymptomatic infection to symptomatic infection that includes diarrhea, myositis, keratitis, and bronchitis. Although rare, encephalitis may also occur.[8] The median incubation time of the disease during foodborne transmission is between the date of the symptoms and onset of illness is about 7 days (range 3 to 15 days). In HIV-infected patients, microsporidia infection is recognized as an increasingly important cause of morbidity and is responsible for significant gastrointestinal (GI) and disseminated disease. On rare occasions, E. bieneusi causes pulmonary infections or infects the bile ducts leading to cholecystitis and cholangitis.[7] Reports of ocular infections with microsporidia are rare but are more common in immunocompromised than in immunocompetent persons.

It remains unknown how much of the spore titer is required for infection in humans, but it appears to vary among the different subspecies. The spores that infect humans are usually 1 to 4 micrometers, and children with an asymptomatic picture appear to have 1.2 x 10 spores of E. bieneusi per gram of feces. Whereas, in HIV-infected patients, the concentration of E. bieneusi spores vary from 4.5 x 10 to 4.4 x 10 per milliliter of diarrheic feces, totaling 10 spores in 24 hours.

Risk Factors

Risk factors associated with microsporidia infection include male-male sexual encounters, intravenous drug use, exposure to swamp water or crop irrigation area, exposure to water with excreta, swimming pool and hot tubs use, or occupational contact with water.[7]

Transmission

Microsporidia disease transmission occurs mostly through food (foodborne disease) including the global food chain industry of fish and crustaceans (shrimp, lobster, clams, among others). Transmission also occurs through water including crop irrigation, seawater, drinking water, groundwater, wastewater, excreta in the environment, and sludge.[9] Vertical transmission from mother to offspring has also been observed in rabbit, sheep, and non-human primates. Zoonotic transmission through animals acting as reservoirs has also been noted in some studies.[10][9] Although rare, the transmission through fecal-oral and aerosols may also occur in human infection cases.[11]

History and Physical

In 1838, Gluge described the earliest report of microsporidia existence when the parasite infected fish. This was later named Glugea anomala. In 1857, Professor Carl Wilhelm von Nageli recognized the first microsporidia Nosema bombycis.[12][1] N. bombycis infected both Lepidoptera and Hymenoptera, causing pebrine/pepper disease, named by Professor Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Breau in Paris. The disease infected silkworm eggs causing the larvae to be covered with blackish blotches. The disease caused by N. bombycis was severe and almost destroyed the European silk industry in France, Italy, and Germany. Nageli first regarded this parasite as a yeast-like organism and classified it as Schizomycetes, a consensus group of yeast and bacteria.

Further microsporidia research included that of Louis Pasteur with his landmark study of N. bombycis. He proposed pebrine disease control and prevention that not only significantly saved the silk industry in Europe but also became the primary influence of Pasteur’s germ theory of disease. The taxonomic determination of microsporidia was controversial for several years, and many researchers proposed they were unicellular algae, yeast spores, fungi-related organism, and even as tumor cells or degraded erythrocytes.[1][12]

After a series of studies on the silkworm pathogen, Balbiani recognized that the organism lacked several Schizomycetes characteristics but shared similarities with the Sporozoa. Consequently, in 1882, Balbiani first suggested the separate taxon Microsporidia for N. bombycis, which was the only named microsporidium at that time. In 1977, Sprague designated the phylum Microspora which was updated in 1992.[13] Later on, Microsporidia were considered a primitive protozoa, but molecular phylogenetic analysis explained that these organisms are not primitive but instead degenerate.

In 2008, Microsporidia were thought to be related to fungi as a sister group or basal branch.[14] Biologists turned their attention to the Microsporidia in silkworms and found that similar organisms globally distributed among various kinds of animals, generally invertebrates and fish, but also humans.

Recent classification in 2012 suggested that Microsporidia are a single-cell eukaryotic (protist) parasite that belong to the SAR-inclusive class or super-group.[2] The members of this group include Stramenopila, Alveolata, Foraminifera, Cercozoa, and Polycystinea.[2]

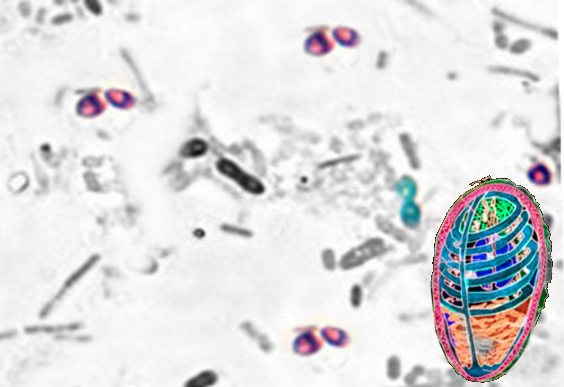

Morphology and Life Cycle

Microsporidia are eukaryotic obligate intracellular organisms with oval appearance under a microscope and present with a nuclear envelope intracytoplasmic membrane system, and a chromosome separation on a mitotic spindle. Microsporidia do not have peroxisomes but do have vesicular Golgi bodies and a primitive mitochondrial-like organelle lacking in genome termed as mitosome.[15] Characteristic of spores include their varying in shape and size, and this feature is now used to determine their taxa. The spores are refractile and coated with electron-dense, proteinaceous exospore, an electron-lucent endospore, and an inner membrane or plasmalemma.[12]

Microsporidia produce an environmentally-resistant spore due to its tubular shape which enables them to extrude its coiled, internal polar tube thereby inoculating its content into the nearby host.[8] Due to its electron-dense, glycoprotein-composed, and chitinous cell structure, microsporidian spores are relatively temperature insensitive, can survive in wide-ranging water salinization, and chemicals and persist despite long periods of dehydration.

The life cycle of Microsporidia consists of 2 distinct stages which are merogony or the proliferating stage, and sporogony or infecting or mature stage. Briefly, the life cycle of Microsporidia are:

- Spores enter the host by ingestion and or inhalation. Germination occurs, resulting in an extension of the polar tube and the injection of sporoplasm into the host cell’s cytoplasm by the injecting tube known as the polar tube, a highly unique specialized invasive structure. The injected sporoplasm in some species also is part of the glycocalyx.[15] This glycocalyx is a structure that intrudes on the host cells and transfers nutrition into the microsporidia.

- Sporoplasm later develops into meronts which is the proliferative stage; here replication occurs through fusion with the formation of multinucleate plasmodial. This meront cell membranes thicken and form sporonts.

- The sporonts divide and develop into sporoblast that later enters a mature stage of spore without additional multiplication. The mature form is equipped with the injection apparatus. The presence of the injection apparatus in the spore is a characteristic that sharply defined microsporidia as a monophyletic taxon.

- The host cells later become distended with mature spores, resulting in rupture and release of the spores to the outer milieu or nearby cells inside the body. In a single infection, Microsporidia can multiply into numerous spores creating a basis of enormous reproductive potential resulting in their high pathogenic capability.

Evaluation

Microsporidia are difficult to detect because of their small size, their slowly infecting properties, and sometimes asymptomatic infection. Therefore, there are many undetermined cases of diarrhea worldwide. The organism needs to be visualized using special techniques involving special laboratory facilities and trained personnel to characterize the infection.

Detection of Microsporidia is based on stool examination through microscopic observation. However, the new staining methods including trichrome stain and fluorescence staining using optical brighteners can be useful. Microsporidia can be stained with Gram stain, carbol-fuchsin stain, and with silver stains.[8]

The immunoblot, the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), and Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA) that utilizes monoclonal and polyclonal antibody are also helpful serological assays for in microsporidia characterization.[8] However, serological tests are unreliable in persons with HIV due to immune deficiency.[6]

The molecular characterization including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and nucleotide sequencing are promising highly sensitive assays with a sensitivity of more than 90% for a quick characterization of human-infected microsporidia. The array can simultaneously detect all 4 species of Microsporidia at a sensitivity of 10 spores per 100 microliters of fecal sample.[8] Within hours, the clinician can interpret the result by isolating genetic/nucleic material of Microsporidia and amplifying the certain sequence enzymatically in thermal cyclic condition and then compare it to the control. To determine the genotype of microsporidia in the infecting host, the rRNA sequence is a gold standard for further characterization.

The in vitro and in vivo assays are also developed to propagate microsporidia for study purposes. Microsporidia generally propagate in the insect cells or tissue or amplified with in vivo inoculation, for example, N. bombycis growth in ovarian tissue of Bombyx mori and N. ceranae inoculated in Apis species or the honeybee.[3] Studies show that Microsporidia from samples, including urine, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, feces, duodenal aspirates, conjunctival scraping, corneal biopsies, cerebrospinal fluids, muscle biopsies, and brain tissue, can grow in mammalian cell lines.[16] Parasite such as Nosema algerae, a microsporidian parasite of mosquitoes can be grown in laboratory colonies and propagated under in vitro setting in the pig's kidney cell line. In vitro cultures of fish, Microsporidia have been successfully demonstrated by using epithelial cell cultures of Aedes albopictus at 28 C. Both in vivo and in vitro assays are useful; however, these techniques require trained personnel, adequate facilities, and the right equipment.

Treatment / Management

Frequently administered drugs for treating Microsporidia infection in animal and humans include albendazole and fumagillin. In the past, organic mercury compounds like Nosemack were also tested. However, Nosemack was less effective against the parasite and more toxic to agricultural bees than fumagillin. Fumagilin has amoebicidal properties and in vivo studies show that fumagillin inhibits Nosema apis development in the honeybee. Albendazole is effective and efficient against Encephalitozoon species infecting humans and animals but has variable effectiveness against Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Albendazole inhibits the tubulin polymerization and is also used as an anthelmintic and an anti-fungal agent.[7](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

- Bacterial gastroenteritis

- Cryptosporidiosis

- Cystoisosporiasis

- Cytomegalovirus

- Giardiasis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Tropical sprue

- Viral gastroenteritis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Like other pathogen and infection control, Microsporidia should be managed and prevented with improved hygiene. The improved regulation of water sources, as well as monitoring of excrement in soil and water, are important to lessen waterborne disease transmission. The tight regulation and hygiene improvement procedure in food chain production or industry, including breeding, processing, storing and packaging to control food contamination and pathogen spread, are an crucial.

Media

References

Keeling PJ, Fast NM. Microsporidia: biology and evolution of highly reduced intracellular parasites. Annual review of microbiology. 2002:56():93-116 [PubMed PMID: 12142484]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAdl SM, Simpson AG, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Bass D, Bowser SS, Brown MW, Burki F, Dunthorn M, Hampl V, Heiss A, Hoppenrath M, Lara E, Le Gall L, Lynn DH, McManus H, Mitchell EA, Mozley-Stanridge SE, Parfrey LW, Pawlowski J, Rueckert S, Shadwick L, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, Spiegel FW. The revised classification of eukaryotes. The Journal of eukaryotic microbiology. 2012 Sep:59(5):429-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23020233]

Higes M, García-Palencia P, Martín-Hernández R, Meana A. Experimental infection of Apis mellifera honeybees with Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia). Journal of invertebrate pathology. 2007 Mar:94(3):211-7 [PubMed PMID: 17217954]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDidier ES, Weiss LM. Microsporidiosis: not just in AIDS patients. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2011 Oct:24(5):490-5. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834aa152. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21844802]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLobo ML, Xiao L, Antunes F, Matos O. Microsporidia as emerging pathogens and the implication for public health: a 10-year study on HIV-positive and -negative patients. International journal for parasitology. 2012 Feb:42(2):197-205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.12.002. Epub 2012 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 22265899]

Didier ES, Stovall ME, Green LC, Brindley PJ, Sestak K, Didier PJ. Epidemiology of microsporidiosis: sources and modes of transmission. Veterinary parasitology. 2004 Dec 9:126(1-2):145-66 [PubMed PMID: 15567583]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDidier ES. Microsporidiosis: an emerging and opportunistic infection in humans and animals. Acta tropica. 2005 Apr:94(1):61-76 [PubMed PMID: 15777637]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGhosh K, Weiss LM. Molecular diagnostic tests for microsporidia. Interdisciplinary perspectives on infectious diseases. 2009:2009():926521. doi: 10.1155/2009/926521. Epub 2009 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 19657457]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStentiford GD, Becnel -J, Weiss LM, Keeling PJ, Didier ES, Williams BP, Bjornson S, Kent ML, Freeman MA, Brown MJF, Troemel ER, Roesel K, Sokolova Y, Snowden KF, Solter L. Microsporidia - Emergent Pathogens in the Global Food Chain. Trends in parasitology. 2016 Apr:32(4):336-348. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.12.004. Epub 2016 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 26796229]

Fiuza VRDS, Lopes CWG, Cosendey RIJ, de Oliveira FCR, Fayer R, Santín M. Zoonotic Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes found in brazilian sheep. Research in veterinary science. 2016 Aug:107():196-201. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2016.06.006. Epub 2016 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 27473995]

Didier PJ, Phillips JN, Kuebler DJ, Nasr M, Brindley PJ, Stovall ME, Bowers LC, Didier ES. Antimicrosporidial activities of fumagillin, TNP-470, ovalicin, and ovalicin derivatives in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2006 Jun:50(6):2146-55 [PubMed PMID: 16723577]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHan B, Weiss LM. Microsporidia: Obligate Intracellular Pathogens Within the Fungal Kingdom. Microbiology spectrum. 2017 Apr:5(2):. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0018-2016doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0018-2016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28944750]

Sprague V, Becnel JJ, Hazard EI. Taxonomy of phylum microspora. Critical reviews in microbiology. 1992:18(5-6):285-395 [PubMed PMID: 1476619]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee SC, Corradi N, Byrnes EJ 3rd, Torres-Martinez S, Dietrich FS, Keeling PJ, Heitman J. Microsporidia evolved from ancestral sexual fungi. Current biology : CB. 2008 Nov 11:18(21):1675-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.030. Epub 2008 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 18976912]

Vávra J, Lukeš J. Microsporidia and 'the art of living together'. Advances in parasitology. 2013:82():253-319. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407706-5.00004-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23548087]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLallo MA, Vidoto Da Costa LF, Alvares-Saraiva AM, Rocha PR, Spadacci-Morena DD, Konno FT, Suffredini IB. Culture and propagation of microsporidia of veterinary interest. The Journal of veterinary medical science. 2016 Feb:78(2):171-6. doi: 10.1292/jvms.15-0401. Epub 2015 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 26346746]