Introduction

Boerhaave syndrome typically occurs after forceful emesis and retching. Boerhaave syndrome is a transmural perforation of the esophagus and should be distinguished from Mallory-Weiss syndrome, a nontransmural esophageal tear also associated with vomiting. Since the perforation occurs with emesis, Boerhaave syndrome is usually not truly spontaneous, but this term helps distinguish it from iatrogenic perforation. Vomiting is the most common cause, but any activity that increases intraesophageal pressure can result in this syndrome. This condition can manifest in patients with a typically functioning esophagus, yet there is a subgroup where specific esophageal abnormalities or pathology are identified. Boerhaave syndrome accounts for 10% to 15% of all esophageal perforations.[1]

Diagnosis of this condition can be challenging because the presentation can vary significantly, thus requiring an index of suspicion. Boerhaave syndrome is classically associated with the Mackler triad of vomiting, chest pain, and subcutaneous emphysema. However, patients rarely present with all of these symptoms and often have vague, nonspecific complaints. This can contribute to a delay in diagnosis and poor outcomes. Boerhaave syndrome is one of the most lethal gastrointestinal tract disorders, with a mortality rate of up to 60% with intervention, increasing to nearly 100% without intervention.[2] Treatment is varied and depends on the time of diagnosis and the patient’s clinical condition at presentation. Management can range from conservative management to major surgical resection.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

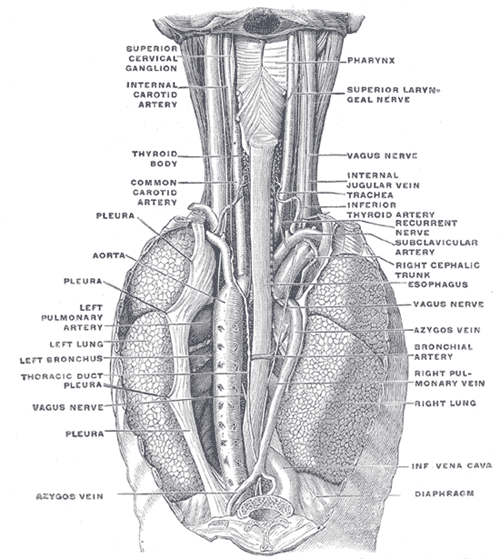

Boerhaave syndrome is a barogenic injury resulting from a sudden increase in intraluminal pressure against a closed cricopharyngeus. Neuromuscular dysfunction results in a non-relaxed cricopharyngeus with a resultant rise in pressure. This pressure overwhelms the wall of the esophagus at its weakest point.[4] In adults, the perforation commonly occurs in the left posterolateral aspect of the distal esophagus below the diaphragm; however, in very young patients, the esophagus usually perforates into the right pleural cavity.

Common risk factors include alcoholism and overindulgence in food. Both can lead to sudden forceful emesis, usually the most common cause. Other causes that raise pressure within the esophagus include weightlifting, defecation, epileptic seizures, abdominal trauma, compressed air injury, and childbirth.[5] Most cases occur in patients with a normal underlying esophagus, although esophagitis and ulcers have also been found in a subset of individuals. No apparent genetic predisposition exists for Boerhaave syndrome.

Epidemiology

Boerhaave syndrome accounts for approximately 15% of all cases of traumatic esophageal rupture. The global estimated incidence of Boerhaave syndrome is approximately 3.1 per 1,000,000 per year, yet this figure is likely underestimated due to underreporting. Boerhaave syndrome has been documented across all racial groups worldwide, predominantly affecting males with male-to-female ratios ranging from 2:1 to 5:1. While the highest risk occurs in men aged in their sixth and seventh decades, Boerhaave syndrome has also been documented in neonates and individuals older than 90. The least affected group appears to be children aged 1 to 17 years.[4]

Pathophysiology

Effort rupture of the esophagus is attributed to a rapid surge in intraesophageal pressure, often linked to forceful vomiting. This is believed to stem from neuromuscular coordination issues, particularly failure in cricopharyngeal relaxation, culminating in a full-thickness tear across the esophagus. This is often associated with overeating and alcohol ingestion.[6]

Typically, perforations occur longitudinally, averaging 3 to 8 cm in size, and are primarily found in the posterolateral lower third of the esophagus, approximately 2 to 3 cm proximal to the gastroesophageal junction. This region is weaker due to a higher concentration of neurovascular structures and a relative absence of longitudinal muscle fibers.[1][7] The upper thoracic or subdiaphragmatic region represents the second most common site for perforation in Boerhaave syndrome.

Associated findings depend on the anatomic location of the rupture. The middle region of the esophagus lies next to the right pleura, while the lower esophagus abuts the left pleura; thus, rupture occurs most commonly in the left pleural cavity. Intrathoracic esophagus perforations can lead to mediastinal inflammation, empyema, emphysema, or necrosis due to gastric contents entering the area. However, rupture may also occur in the cervical or upper thoracic region. Upper thoracic or midesophageal perforations tend to produce right-sided pleural effusion or hydropneumothorax. The cervical ruptures are usually localized and benign, as the spread to the mediastinum through the retroesophageal space is slow and limited.[8][9][10]

History and Physical

The traditionally taught clinical presentation of Boerhaave syndrome, known as the Mackler triad involving vomiting, lower thoracic pain, and subcutaneous emphysema in middle-aged men post excessive food or alcohol intake, is rarely observed. Instead, the presentation is often more nonspecific, with many possible symptoms.[11] This variability is due to the anatomy of the esophagus and its occupation within several spaces (ie, cervical, thoracic, abdominal). Approximately 25% to 45% of patients have no history of vomiting upon presentation, and rupture can occur at any age and in all ethnicities and genders.[12]

The clinical presentation also depends on the time elapsed since the injury and the extent of leakage. Patient complaints can vary greatly and may consist of sudden onset of chest, neck, and abdominal pain, odynophagia, dysphagia, hoarseness, dysphonia, vomiting, hematemesis, and respiratory distress. Physical examination may reveal subcutaneous crepitation, mediastinal crunching sounds synchronized with each heartbeat in the left lateral decubitus position (Hamman sign), fever, hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, cyanosis, decreased breath sounds, abdominal pain, abdominal rigidity, neck pain, tracheal shift, proptosis, and altered mental status.

Evaluation

The evaluation consists mainly of physical examination and radiographic assessment. A focused physical examination is essential to ascertain the degree of distress or physiologic derangement.

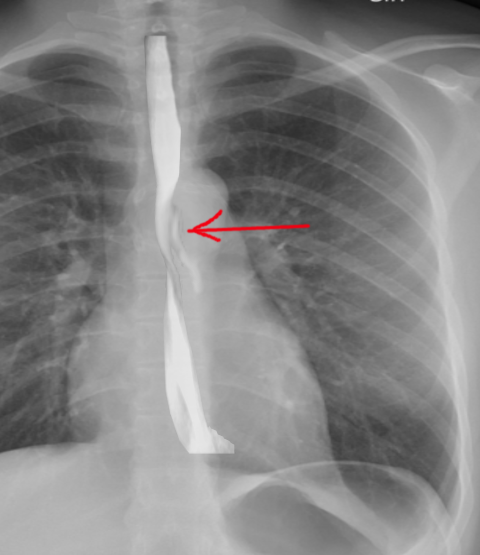

Imaging is critical in diagnosing Boerhaave syndrome. Plain films of the chest and abdomen may show subcutaneous or mediastinal emphysema, mediastinal widening, and pleural effusion. In up to 20% of cases, the Nacleario V-sign may be seen as radiolucent streaks that dissect the retrocardiac fascia to form the letter V. This is a specific but insensitive radiographic sign of esophageal perforation.

Laboratory tests are often nonspecific in the diagnosis of Boerhaave syndrome. Patients may have a leukocytosis with a left shift, and many have a hematocrit value of around 50% due to hemoconcentration from fluid loss. Sampling from a present pleural effusion may show undigested food particles and gastric fluid. Lab results usually reveal a pH of less than 6 and an elevated salivary amylase level.

A contrast esophagogram may aid in diagnosis. A water-soluble contrast agent such as Gastrografin should be used since extravasation of barium can lead to mediastinitis and subsequent fibrosis. The sensitivity of this study is dependent upon the size and location of the perforation and technique. False-negative results occur in 10% to 38% of cases.[13] The study may be repeated with barium if the initial test with water-soluble contrast is negative.

CT imaging aids in a more definitive diagnosis and may be better tolerated in severely ill patients. CT imaging provides more detail regarding the location of drainable collections and aids in localizing the rupture site. A contrast medium may further define the injury extent and assist in a timely diagnosis. CT findings may include periesophageal and mediastinal gas, mediastinal fluid collections, esophageal wall thickening, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, and hydrothorax.[13]

Endoscopy is considered controversial as it increases the risk of further esophageal perforation. Endoscopy should be reserved for patients whose perforation location is unclear and who are appropriate candidates for endoscopic treatment.

Treatment / Management

The 3 common treatment modalities for Boerhaave syndrome include nonsurgical, endoscopic, and surgical (open vs minimally invasive). The management decision is best made by an interprofessional team with experience in all treatment options.[14] Treatment often consists of a combination of medical and surgical interventions. The mainstay of treatment includes avoidance of all oral intake, volume replacement, broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, nutritional support (usually parenteral), source control of any leaks (eg, via IR or VATS), and prompt surgical or endoscopic intervention as indicated. Treatment approaches are typically customized based on the perforation's location and size, the duration between injury and diagnosis, and the patient's overall condition. Early diagnosis (within 12 to 24 hours) yields the best outcome. (B3)

Criteria for patients who are candidates for medical management include the following:

- The leak is contained within the neck or mediastinum or between the mediastinum and visceral lung pleura.

- Contrast can flow back into the esophagus from the cavity surrounding the perforation.

- The injury is not in neoplastic tissue, in the abdomen, or proximal to an obstruction.

- The patient has minimal symptoms with no signs of sepsis.

- Contrast studies can be obtained at any time of day.

- Surgical specialists are readily available if the patient deteriorates.[15] (B3)

Medical management includes avoidance of all oral intake for at least 7 days, parenteral nutrition, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics for 7 to 14 days, and drainage of any fluid collections. Patients who show signs of clinical deterioration during conservative treatment require surgical intervention. Surgery is indicated if any of the following develops: contained perforation develops into a free perforation, the injury extends, the patient exhibits persistent fevers, clinical deterioration including the development of sepsis, progression of pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum, or development of empyema. The most successful surgical method often entails primary esophageal repair, particularly within the first 4 hours of perforation. This can be achieved through open thoracotomy vs VATS with fundic reinforcement, which is now considered the gold standard of treatment.

In a diseased, nonviable segment of the esophagus, resection may be the best treatment. In late presentations diagnosed after 24 hours, the wound edges are typically edematous, stiff, or friable, rendering primary repair risky. Considering this, many manage late perforations with debridement of the pleural cavity and mediastinum, esophagostomy, and feeding gastrostomy. Definitive reconstruction may be performed after 6 weeks. Although surgery is the most common treatment of Boerhaave syndrome, stenting across the leak has been used with promising results in some instances.[16] This option might be considered in patients with significant underlying comorbidities. Advanced endoscopic techniques can provide patients with a minimally invasive therapeutic intervention. Endoscopic approaches for managing esophageal perforation include placement of fully covered esophageal stents, through-the-scope clips, over-the-scope clips, and endoscopic suturing, esophageal resection and diversion.[17]

Differential Diagnosis

Symptoms of Boerhaave syndrome are often nonspecific and may be seen with many other conditions such as aortic dissection, pancreatitis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolus, perforated peptic ulcer, spontaneous pneumothorax, pneumonia, pericarditis, or Mallory-Weiss tear. These disorders can be distinguished from Boerhaave syndrome by history, physical examination, laboratory evaluation, electrocardiogram, and other imaging.[18]

Prognosis

The prognosis often depends on the time between injury and diagnosis. Delayed diagnosis and treatment are associated with worse outcomes and increased mortality. When diagnosis and appropriate treatment occur within 12 to 24 hours, patients have a good prognosis with a survival rate approaching 75%. Boerhaave syndrome, if left untreated, has a mortality rate of over 90%.[19]

Complications

Boerhaave syndrome is an uncommon condition, and the diagnosis can easily be missed or delayed, leading to complications like dehydration, mediastinitis, sepsis, ARDS, massive pleural effusion, esophageal fistula, empyema, shock, and death.[20]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Recovery from a transmural esophageal rupture depends on the tear's severity, intervention, and degree of systemic impact. Rehabilitation may consist of reintroducing feeding, normalizing organ systems, weaning from intensive measures (such as mechanical ventilation and invasive monitoring), and regaining strength and endurance to allow, when possible, eventual independent activities of daily living.

Consultations

Thoracic and general surgery consults should be made early in the care of the patient with suspected Boerhaave syndrome. Additional consultations may include infectious disease and critical care specialists.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Boerhaave syndrome is rare, with no predictive models. Patients with known excessive use of alcohol and binge eating should be educated regarding the pathology. They should be counseled that any sudden chest, neck, or abdominal pain with forceful emesis while indulging should be evaluated immediately. Those with Boerhaave syndrome merit close follow-up with gastroenterology and their primary care provider.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about Boerhaave syndrome are as follows:

- The diagnosis of Boerhaave syndrome requires a high degree of suspicion.

- A delay in the diagnosis leads to worse outcomes and can be potentially fatal.

- Imaging with water-soluble contrast in lieu of barium should be used to avoid mediastinal injury with barium contrast.

- If the perforation is small and contained, a conservative approach can be attempted, but surgery should be the mainstay in cases of frank extravasation and clinical deterioration.

- VATS with fundic reinforcement is the gold standard of treatment; endoscopic repair is becoming more prevalent.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Boerhaave syndrome is often difficult to diagnose, leading to a high mortality rate. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are paramount to good outcomes. While a surgical team is almost always involved in managing this condition, it is essential to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that includes a radiologist, gastroenterologist, intensivist, pharmacist, and possibly an infectious disease specialist. The nursing staff are vital as they monitor the patient's vital signs and overall status and assist with educating the patient and family. Communication and collaboration among all team members are essential in providing the most thorough and attentive care possible to ensure the best possible outcome. Timely involvement of all members is imperative in this dangerous condition.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Harikrishnan S, Murugesan CS, Karthikeyan R, Manickavasagam K, Singh B. Challenges faced in the management of complicated Boerhaave syndrome: a tertiary care center experience. The Pan African medical journal. 2020:36():65. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.36.65.23666. Epub 2020 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 32754292]

Cuccì M, Caputo F, Fraternali Orcioni G, Roncallo A, Ventura F. Transition of a Mallory-Weiss syndrome to a Boerhaave syndrome confirmed by anamnestic, necroscopic, and autopsy data: A case report. Medicine. 2018 Dec:97(49):e13191. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013191. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30544378]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAiolfi A, Micheletto G, Guerrazzi G, Bonitta G, Campanelli G, Bona D. Minimally invasive surgical management of Boerhaave's syndrome: a narrative literature review. Journal of thoracic disease. 2020 Aug:12(8):4411-4417. doi: 10.21037/jtd-20-1020. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32944354]

Khadka B, Khanal K, Dahal P, Adhikari H. A rare case of Boerhaave syndrome with cervico-thoracic esophageal junction rupture causing bilateral empyema; case report from Nepal. International journal of surgery case reports. 2023 Apr:105():108018. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.108018. Epub 2023 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 36996703]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBury J, Fratczak A, Nielson JA. Atypical Presentation of Boerhaave Syndrome With Hypoxia and Unresponsiveness. Cureus. 2022 Aug:14(8):e27848. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27848. Epub 2022 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 36110495]

Tanaka H, Uemura N, Nishikawa D, Oguri K, Abe T, Higaki E, Hosoi T, An B, Hasegawa Y, Shimizu Y. Boerhaave syndrome due to hypopharyngeal stenosis associated with chemoradiotherapy for hypopharyngeal cancer: a case report. Surgical case reports. 2018 Jun 8:4(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s40792-018-0462-z. Epub 2018 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 29884971]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAriza-Traslaviña J, Caballero-Otálora N, Polanía-Sandoval CA, Perez-Rivera CJ, Tellez LJ, Mosquera M. Two-staged surgical management for complicated Boerhaave syndrome with esophagectomy and deferred gastroplasty: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2023 Feb:103():107881. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.107881. Epub 2023 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 36640469]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceY K, F AB, A T, D H. Boerhaave syndrome in an elderly man successfully treated with 3-month indwelling esophageal stent. Radiology case reports. 2018 Oct:13(5):1084-1086. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2018.04.026. Epub 2018 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 30228849]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYap D, Ng M, Mbakada N. A rare complication of ileostomy obstruction: Boerhaave syndrome. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2018 Aug 16:100(8):e1-e4. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2018.0129. Epub 2018 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 30112937]

Lieu MT, Layoun ME, Dai D, Soo Hoo GW, Betancourt J. Tension hydropneumothorax as the initial presentation of Boerhaave syndrome. Respiratory medicine case reports. 2018:25():100-103. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2018.07.007. Epub 2018 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 30101056]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan der Weg G, Wikkeling M, van Leeuwen M, Ter Avest E. A rare case of oesophageal rupture: Boerhaave's syndrome. International journal of emergency medicine. 2014:7():27. doi: 10.1186/s12245-014-0027-2. Epub 2014 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 25364474]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWilson RF, Sarver EJ, Arbulu A, Sukhnandan R. Spontaneous perforation of the esophagus. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1971 Sep:12(3):291-6 [PubMed PMID: 5112482]

Tonolini M, Bianco R. Spontaneous esophageal perforation (Boerhaave syndrome): Diagnosis with CT-esophagography. Journal of emergencies, trauma, and shock. 2013 Jan:6(1):58-60. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.106329. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23493470]

Carrott PW Jr, Low DE. Advances in the management of esophageal perforation. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2011 Nov:21(4):541-55. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.08.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22040636]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIvey TD, Simonowitz DA, Dillard DH, Miller DW Jr. Boerhaave syndrome. Successful conservative management in three patients with late presentation. American journal of surgery. 1981 May:141(5):531-3 [PubMed PMID: 6784584]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHauge T, Kleven OC, Johnson E, Hofstad B, Johannessen HO. Outcome after stenting and débridement for spontaneous esophageal rupture. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2018 Apr:53(4):398-402. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1448886. Epub 2018 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 29523026]

Barakat MT, Girotra M, Banerjee S. (Re)building the Wall: Recurrent Boerhaave Syndrome Managed by Over-the-Scope Clip and Covered Metallic Stent Placement. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2018 May:63(5):1139-1142. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4756-y. Epub 2017 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 28948439]

Chen YH, Lin PC, Chen YL, Yiang GT, Wu MY. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography Helped to Rapidly Detect Pneumomediastinum in a Vomiting Female. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2023 Feb 17:59(2):. doi: 10.3390/medicina59020394. Epub 2023 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 36837595]

Wiggins B, Banno F, Knight KT, Fladie I, Miller J. Boerhaave Syndrome: An Unexpected Complication of Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Cureus. 2022 May:14(5):e25279. doi: 10.7759/cureus.25279. Epub 2022 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 35755500]

Kakar N, Smith HC, Shadid AM. Prolonged Emesis Causing Esophageal Perforation: A Case Report. Cureus. 2022 May:14(5):e24720. doi: 10.7759/cureus.24720. Epub 2022 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 35673315]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence