Introduction

Wilson disease, also known as hepatolenticular degeneration, is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the ATP7B gene, leading to abnormal copper accumulation in the liver, brain, cornea, and other organs. This condition primarily affects the liver, brain, cornea, and lens but can also impact other organ systems, including the heart, leading to nonischemic cardiomyopathy, and the bones, resulting in arthritis, and the kidneys, causing proximal renal tubular dysfunction.

Overt symptoms are primarily related to the nervous and hepatic systems. Liver-related symptoms include jaundice and pruritus, as well as nonspecific nausea, vomiting, and lower extremity edema. Jaundice is primarily driven by concurrent hemolytic anemia. Extrapyramidal symptoms include neuropsychiatric symptoms, including tremors, hypophonia, dysarthria, mood or personality changes, anxiety, and auditory or visual hallucinations. Most individuals with Wilson disease present with liver-related symptoms in the first decade of life and neuropsychiatric symptoms within the third or fourth decades of life. Wilson disease is rare and, if not recognized or treated, can be fatal.

The condition is typically diagnosed through serologic and urine testing, ocular examinations, and, in some cases, liver biopsy. If untreated, Wilson disease can be fatal, particularly due to acute liver failure. Treatment involves copper chelation therapy using agents like D-penicillamine and trientine, as well as zinc supplementation to reduce copper absorption. In severe cases, liver transplantation may be necessary. Emerging therapies, including novel chelators and gene therapy approaches, are under investigation. Early detection and lifelong management are critical for improving patient outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Wilson disease is an autosomal recessive condition caused by 1 of several mutations in ATP7B gene which encodes the ATP7B protein transporter on the long arm of chromosome 13 (13q) responsible for excreting excess copper into bile and out of the body. This protein transporter is in the trans-Golgi network of hepatocytes. More than 300 mutations have been described, and most patients are compound heterozygotes, meaning they have 2 different mutations, 1 on each chromosome.[1]

The primary route of copper excretion is through the liver. The excess copper first accumulates in the liver and then accumulates in the blood, where it is distributed to other organ systems. Furthermore, the excess copper leads to the generation of free radicals, which in turn cause the oxidation of vital proteins and lipids. Early cellular changes typically occur in the mitochondria, nuclei, and peroxisomes.

Epidemiology

This disease affects 1 in every 30,000 individuals, with a carrier frequency of 1 in every 90 people. An equal predilection between males and females is demonstrated in patients with Wilson disease. The usual age of presentation is between the first and fourth decades of life, but it has been detected in children as young as 3 and adults as old as 70.[2]

Pathophysiology

Through faulty copper excretory mechanisms, excess copper accumulates in the liver and spills into the blood, accumulating in other organs and tissues, particularly in the brain, kidney, and eyes. Excess copper then leads to the formation of a toxic hydroxyl group, increasing oxidative stress in the cells and damaging tissue, which can result in organ dysfunction and clinical symptoms, including liver failure, neuropsychiatric symptoms, movement disorders, and Kayser-Fleischer (KF) rings in the cornea.

Copper is an essential mineral, primarily serving as a cofactor for enzymes, eg, ceruloplasmin, cytochrome c oxidase, dopamine beta-hydroxylase, superoxide dismutase, and tyrosinase. Copper enters the body through the digestive tract via transporter proteins in the small intestine, specifically copper transporter 1 (CTR1; SLC31A1). This transporter facilitates the uptake of copper into cells, where copper is bound to metallothionein. Part is carried by an antioxidant copper chaperone (ATOX1) to the trans-Golgi network. In response to rising intracellular copper levels, ATP7B releases copper into the portal vein, which flows towards the liver. Hepatocytes carry the metalloenzymes, where ATOX1 binds inside the cell. Then, ATP7B links the copper to ceruloplasmin and releases it into the bloodstream, removing excess copper by secreting it into bile. In Wilson disease, dysfunctional ATP7B leads to copper accumulation in the liver, and ceruloplasmin is secreted in a form that lacks copper and is rapidly degraded in the bloodstream.

When the copper level in the liver exceeds the naturally bound proteins, it leads to oxidative damage by forming reactive oxygen species. This damage results in active hepatitis and fibrosis, with serologic manifestations including elevation of serum transaminases, specifically aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT). The alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is commonly low or normal despite hepatic inflammation. Although this is not yet fully understood, several hypotheses have been proposed. ALP is a metalloenzyme that requires zinc as a necessary cofactor.[3] Studies have suggested that copper displaces zinc, leading to a decrease in ALP function, as well as the potential for a conformational change in the metalloenzyme, which in turn decreases serum levels.[4] The elevation in serum bilirubin is commonly indirect and associated with hemolysis, as discussed below. A major serologic hallmark of the presentation is a low serum ALP and high total bilirubin (TB) level. This results in an ALP: TB ratio of <4, with a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 96%.[5]

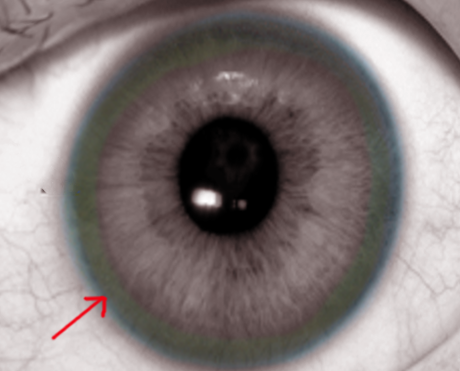

The liver releases copper into the bloodstream that is not bound by ceruloplasmin. This free copper is deposited in several organs, including the brain, the kidneys, and the eyes. In the brain, copper deposits in the basal ganglia, putamen, and globus pallidus are involved in the coordination of movement and neurocognitive processes, eg, mood regulation. In the eyes, the accumulation of free copper in the cornea leads to KF rings, whereas the accumulation of free copper in the lens leads to sunflower cataracts. The accumulation of free copper in the bloodstream leads to oxidative damage to erythrocytes, resulting in intravascular hemolysis, which in turn causes the notable indirect hyperbilirubinemia and overt jaundice characteristic of this condition. In the kidney, there is direct copper toxicity to renal tubular cells, as well as the potential bile cast nephropathy due to acute hemolysis.

Histopathology

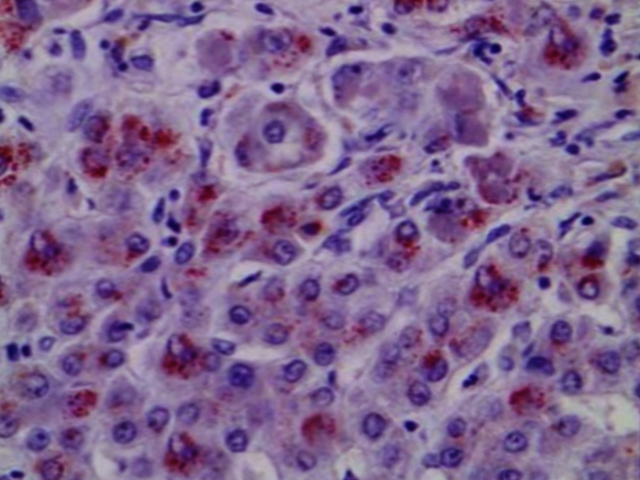

For patients with inconclusive initial serologic and urine testing who undergo a liver biopsy, conventional light microscopy may reveal various pathologic changes commonly seen in other hepatic conditions. Liver biopsies may demonstrate fatty infiltration with Mallory Hyaline bodies and steatohepatitis, which is seen in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) (see Image. Wilson Disease). A biopsy may also show findings of interface hepatitis, which is typically seen in autoimmune hepatitis. Rhodanine stain is used to identify copper deposits. A diagnosis of Wilson disease is established if the hepatic iron concentration is >250 µg/g dry weight (or approximately 4 µmol/g dry weight) with a normal hepatic iron concentration being 15 to 55 µg/g dry weight.

History and Physical

Clinical Features

Given the predilection for excess copper accumulation and oxidative damage to the basal ganglia, including the putamen and globus pallidus, which are involved in the coordination of movement and neurocognitive processes, patients may report symptoms, eg, weakness, personality changes, depression, headaches, insomnia, and tremors. Approximately 30% to 50% of patients will have neuropsychiatric symptoms, including an asymmetric tremor. Other symptoms may include ataxia, hypophonia, dysarthria, and clumsiness. Renal symptoms are due to varying degrees of tubular dysfunction with a spectrum including hydroelectric acid-base disorders, nephrolithiasis, urolithiasis, bile cast nephropathy, and Fanconi syndrome.

Physical examination may demonstrate hepatosplenomegaly. If the disease has progressed to cirrhosis, stigmata of chronic liver disease may be present. Ocular examination may reveal scleral icterus, and slit-light examination may demonstrate KF rings in the cornea or sunflower cataracts in the lens (see Image. Kayser-Fleischer Rings). However, neither of these findings are specific to Wilson disease. Other features of Wilson disease may include movement disorders, spasticity, rigidity, tremors, hypophonia, and dysarthria. Skeletal involvement is common, typically resembling early osteoarthritis, and involves the axial skeleton and spine.

Individuals may present with acute liver failure (ALF) in a state of fulminant Wilson disease manifested by impaired synthetic dysfunction with an international normalized ratio (INR) ≥1.5 and acute encephalopathy in a patient without cirrhosis or preexisting liver disease.[6] These patients should be urgently evaluated at a liver transplant center for orthotopic liver transplantation, given the high mortality.

Evaluation

Laboratory Studies

Wilson disease is a rare cause of liver disease and typically presents before the fifth decade of life. This condition is a common diagnosis evaluated for in individuals with chronic liver disease and is particularly important for those with liver disease at a younger age. However, Wilson disease should also be highly suspected if the individual has a history of neuropsychiatric symptoms or an ALP:TB ratio of <4.

Several potential diagnostic approaches for Wilson disease may be utilized. The diagnostic algorithm typically involves serologic testing, urine testing, and an ocular exam. The first serologic test recommended is serum ceruloplasmin, where a level of <20 mg/dL indicates an abnormality. Ceruloplasmin testing in isolation has a low positive predictive value, ranging from 0.6% to 8%, and a low negative predictive value, ranging from 35% to 50%.[7] Other forms of chronic liver disease may exhibit low serum ceruloplasmin levels. If ceruloplasmin is <20 mg/dL, the patient should undergo a 24-hour urine copper evaluation. A level >40 µg (typically >100 µg) demonstrates an abnormality. A ceruloplasmin level of <5 mg/dL suggests aceruloplasminemia, a disease caused by mutations in the ceruloplasmin gene, resulting in the absence of ceruloplasmin and cerebral iron deposition.

Additional Diagnostic Studies

Patients should also undergo a slit-lamp exam with an ophthalmologist to evaluate for KF rings and sunflower cataracts. Abnormal ceruloplasmin levels, 24-hour urine copper levels, and KF rings are diagnostic for Wilson disease. If the patient has 2 of 3 serologic abnormalities or an alternative diagnosis is suspected, they should undergo liver biopsy with copper quantification, where a presence of >250 µg/g dry weight is diagnostic for Wilson disease. The patient should undergo molecular testing if hepatic copper quantification is 50 to 250 µg/g dry weight.

If neurologic symptoms are present, individuals should undergo evaluation with brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess for cerebral involvement, which typically displays hyperintensities in the basal ganglia, putamen, and globus pallidus on the T2 sequence, corresponding to heavy metal deposition. An ECG may demonstrate right ventricular hypertrophy and nonspecific changes to T-waves and ST segments.

Molecular testing is typically not recommended as a first-line evaluation of Wilson disease due to the likelihood of compound heterozygosity. First and second-degree relatives of diagnosed patients should be screened for Wilson disease using molecular testing.

Leipzig Scoring

The Leipzig scoring system was previously proposed, which includes the presence of typical clinical signs and symptoms, including KF rings, neurologic symptoms, serum ceruloplasmin, and Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia, as well as other tests, including hepatic copper quantification, urinary copper excretion (in the absence of acute hepatitis), and mutation analysis. A composite score of 4 or higher establishes the diagnosis.[8]

Treatment / Management

Liver Transplantation

Individuals with acute Wilsonian hepatitis manifesting with ALF should be urgently evaluated at a liver transplant center. A liver transplant is curative.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies

Copper exposure restriction

Eliminating any supplemental copper intake, whether intentional or unintentional, is essential. Individuals should be referred to a nutritionist for education on foods rich in copper, eg, organ meats, mushrooms, and chocolate. Patients should be advised to avoid using copper-coated appliances and cookware. If consuming well water, test it for copper content. If an individual's home has copper plumbing and pipes, flushing them by running water through the pipes before use is recommended. Dietary copper restriction is typically insufficient as monotherapy for Wilson disease.

Physical and occupational therapies

Physical and occupational therapy are beneficial for the neurologic component of the disease. The copper-chelating treatment may take several months to demonstrate neurologic recovery and improvement. These therapies can assist with ataxia, dystonia, and tremors and prevent contractures that can result from longstanding dystonia.

Pharmacologic Therapies

Chelation

For nonfulminant Wilson disease, copper chelation is the mainstay therapy and should be implemented for patients with any degree of organ involvement. Individuals diagnosed with a screening approach may consider nonchelation therapies. Several chelators are available, including D-penicillamine and trientine. Treatment with any chelating agent may initially worsen neurologic symptoms within the first 3 weeks of treatment; discontinuation is not recommended. Both should be administered either 1 hour before or 2 hours after meals, considering the reduced enteric bioavailability when given with food.

Chelation therapy is not specific to copper and may also chelate iron and zinc. Dose reduction should be performed for patients undergoing surgery or pregnancy due to the risk of impaired wound healing. Oral copper chelation dosing should be titrated to achieve 24-hour urine copper levels of >100 μg. The choice of copper chelation agent should be based on the availability of the agent, its safety profile, the patient's comorbidities, clinical experience, and the cost of the drug. All copper chelators are considered safe for use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Trientine inhibits intestinal copper absorption and increases urinary copper excretion. The coadministration of trientine with iron can form a toxic complex; therefore, separating them by at least 2 hours is advised. Trientine has several adverse effects, including aplastic anemia and gastritis. Initial treatment dosing begins with 15 to 20 mg/kg/day (maximum 1500 mg/day) in 2 to 3 divided doses, then increased over a 2-to-3-week period to a maximum of 2000 mg/day. Maintenance dosing is reduced: For adults, the target dose is 10 to 15 mg/kg/day in divided doses, and for pediatrics, the target dose is 20 mg/kg/day (rounded to the nearest 250 mg) in divided doses. Doses >20 mg/kg/day increased the risk of adverse events.

D-penicillamine increases urinary copper excretion. D-penicillamine should be immediately discontinued if adverse early sensitivity reactions, including fever, rash, and proteinuria, are noted. Other adverse effects include aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elastosis perforans serpingosa. Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and severe thrombocytopenia are at higher risk for toxicity and should consider trientine therapy. D-penicillamine is associated with the inactivation of pyridoxine (vitamin B6); therefore, experts recommend supplementing with 25 to 50 mg daily. Initial treatment should start at 250 to 500 mg/kg/day, increased by 250 mg increments every 4 to 7 days to reach 1000 to 1500 mg/day (maximum 2000 mg/day) in 2 to 4 divided doses. Maintenance therapy for adults is reduced to 750 to 1000 mg/day in 2 divided doses. In pediatrics, the recommended dosage is 20 mg/kg/day (rounded to the nearest 250 mg) in divided doses.

Nonchelation

Oral zinc interferes with enteric copper absorption and thereby increases copper stool excretion. Zinc is typically used as a mainstay therapy following treatment with other copper chelators and not as monotherapy. Zinc supplementation may lead to a transient elevation in serum lipase and amylase without clinical or radiographic evidence of pancreatitis. Initial treatment dosing for adults and children weighing >50 kg is 150 mg/day in divided doses. Children weighing <50 kg and older than 5 years should be dosed at 75 mg/day in divided doses. Children under 50 kg and younger than 5 years should be administered a dosage of 50 mg/day in divided doses.[9]

Assessing Response to Therapy

Monitoring during chelation therapy is recommended and involves regular evaluation of 24-hour urine copper excretion, liver biochemistries, INR/PT, complete blood count, routine urinalysis, serum copper levels, and ceruloplasmin.

Initial response to copper chelation with either trientine or D-penicillamine should demonstrate a 24-hour urine copper of 1000 to 2000 μg (16-32 μmol), and maintenance therapy should demonstrate a 24-hour urine copper of 150 to 500 μg (2.4-8 μmol). Zinc monotherapy may show a modest 24-hour urine copper excretion, if any.

Novel Therapies and Future Directions

A newer formulation of trientine, trientine tetrachloride, with improved pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, is under trial. This therapy has demonstrated increased absorption rates compared to traditional trientine, resulting in increased systemic bioavailability in a phase 1 single-dose study.[10] The CHELATE trial demonstrated the noninferiority of trientine tetrachloride compared to D-penicillamine in maintaining stable nonceruloplasmin-bound copper over a 24-week follow-up in a phase 3 randomized clinical trial.[11] The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved trientine tetrachloride for patients with Wilson disease. Current trials are underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a once-daily formulation of trientine tetrachloride, as it may be an efficacious strategy to reduce multiple-dose requirements and patient adherence.(A1)

Given the genetic etiology of Wilson disease, therapies directed at gene correction remain a possibility. This has been successfully explored using CRISPR/Cas9 through gene-corrected patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived hepatocytes (iHeps) to restore both in vitro and in vivo ATP7B function in a mouse model from hepatocytes derived from a patient with Wilson disease.[12] Through another mechanism, copper metabolism has been restored in murine models using adeno-associated serotype 8 vector (AAV8), though the gene size was too large, limiting the vector's distribution ability.[13]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes various conditions involving the hepatobiliary system and hemolytic anemias, including alcohol-related liver disease, alcohol-associated hepatitis, Zieve’s syndrome, viral hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, autoimmune hepatitis, MASLD, hereditary hemochromatosis, thrombotic microangiopathic hemolytic anemias, and Evan’s syndrome. The neuropsychiatric symptoms can be mistaken for Parkinsonian syndromes, Wernicke encephalopathy, pantothenate kinase deficiency associated neurodegeneration, neuroacanthocytosis syndrome, and Huntington disease. A thorough patient history, appropriate laboratory studies, and, when indicated, a liver biopsy should be performed. (Please refer to the Evaluation section for more information on these diagnostic studies.)

Staging

Wilson Disease is staged using the following criteria:

- Stage 1: Initial accumulation of copper in the liver

- Stage 2: Acute redistribution of copper within the liver, followed by release into the systemic circulation

- Stage 3: Chronic accumulation of copper in extrahepatic tissues

- Stage 4: Use of chelation therapy to restore copper balance

Prognosis

The prognosis of untreated Wilson disease is poor, with a median life expectancy of 40 years of age, with most patients dying of liver-related complications. Individuals may have a normal life expectancy if diagnosed early and responsive to copper chelation therapy.

Separately, prognostic indices have previously been proposed. The Nazer score (also referred to as the King’s score) assigns a scoring template to levels of serum bilirubin, AST, and prothrombin time (PT), ranging from 0 to 4 points, with a total score range of 0 to 12. Individuals with ≥7 composite points had a 100% mortality rate during their admission, while those with scores ≤6 predicted a response to chelation therapy.[14] The Nazer score was modified to include serum leukocytes and albumin, with scores of ≥11 predicting death without liver transplantation.[15]

For individuals with Wilson disease and liver disease, the utilization of the Model for End-stage Liver Disease 3.0 score provides a prognosis regarding their estimated 90-day mortality, as well as prioritizes the receipt of liver transplantation in those without acute Wilsonian hepatitis. Individuals with acute Wilsonian hepatitis or patients with Wilson disease in ALF have a high mortality rate, and the disease is nearly always fatal.[16] They should undergo urgent liver transplant evaluation. If listed for liver transplantation, they are categorized by United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Status 1A. Following liver transplantation, the prognosis is generally favorable, with 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates of 90.6%, 83.7%, and 79.9%, respectively.[17]

A recent systematic review encompassing 48 studies found that liver transplantation significantly improved outcomes in 71.2% of 215 patients with Wilson disease presenting with neurological symptoms. Among the remaining patients, 6.9% experienced no change in symptoms, 7.9% showed worsening neurological symptoms, 9.6% died, and 4.3% were lost to follow-up.[18]

Complications

Complications of Wilson disease include both hepatic and extrahepatic systems. The hepatic complications include ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatocellular carcinoma, ALF, and death. Extrahepatic complications are widespread and can involve the nervous, hematologic, ophthalmologic, renal, and cardiac systems. Neuropsychiatric involvement indicates a poor prognosis and may feature extrapyramidal symptoms of dysarthria, dystonia, tremors, and ataxia, as well as behavioral changes with irritability, aggression, anxiety, and personality changes.

Patients may develop a Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia and rhabdomyolysis. Ocular complications reduced visual acuity due to sunflower cataracts. KF rings may develop but are often asymptomatic. Cardiac abnormalities may develop with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias or cardiac conduction issues. Chelation therapy may improve complications; however, patients may experience acute worsening of neurologic symptoms before improvement. Liver transplantation is curative.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Early diagnosis and treatment of Wilson disease is imperative in reducing complications. Patients should be educated about potential unintentional copper intake, including through well water, plumbing systems, and cookware. Maintaining long-term adherence to copper chelation therapy is essential for minimizing the progression of the disease. Patients should avoid alcohol and hepatotoxic substances. Patients should be educated on the importance of genetic testing first-degree relatives to assist in prompt diagnosis and initiation of therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of Wilson disease requires an interprofessional approach that integrates the expertise of physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and rehabilitation specialists. Physicians and advanced practitioners are responsible for early recognition, diagnosis, and treatment initiation, ensuring patients receive timely chelation therapy and monitoring for disease progression. Primary care clinicians collaborate with specialists, including hepatologists and neurologists, to tailor treatment plans based on disease severity. Nurses play a key role in patient education, emphasizing the importance of medication adherence, lifestyle modifications, and vaccination against hepatitis A and B. Pharmacists contribute by assessing potential drug interactions, optimizing chelation therapy regimens, and providing guidance on medication side effects.

Interprofessional communication and coordination are essential for delivering patient-centered care and improving outcomes. Regular team meetings help ensure treatment plans are aligned, and electronic health records facilitate seamless information sharing. Physical and occupational therapists assist in managing extrapyramidal symptoms through rehabilitation programs that enhance mobility and prevent complications like contractures. By fostering collaboration among healthcare professionals, patients receive comprehensive care that prioritizes safety, adherence, and long-term disease management. This integrated strategy enhances patient outcomes, minimizes complications, and supports a holistic approach to managing Wilson disease.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Chang IJ, Hahn SH. The genetics of Wilson disease. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2017:142():19-34. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63625-6.00003-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28433102]

Liu J, Luan J, Zhou X, Cui Y, Han J. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of Wilson's disease. Intractable & rare diseases research. 2017 Nov:6(4):249-255. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2017.01057. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29259852]

Lowe D, Sanvictores T, Zubair M, John S. Alkaline Phosphatase. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083622]

Csopak H, Falk KE. The specific binding of copper(II) to alkaline phosphatase of E. coli. FEBS letters. 1970 Apr 2:7(2):147-150 [PubMed PMID: 11947454]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKorman JD, Volenberg I, Balko J, Webster J, Schiodt FV, Squires RH Jr, Fontana RJ, Lee WM, Schilsky ML, Pediatric and Adult Acute Liver Failure Study Groups. Screening for Wilson disease in acute liver failure: a comparison of currently available diagnostic tests. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2008 Oct:48(4):1167-74. doi: 10.1002/hep.22446. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18798336]

Lee WM, Stravitz RT, Larson AM. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Position Paper on acute liver failure 2011. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2012 Mar:55(3):965-7. doi: 10.1002/hep.25551. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22213561]

Tapper EB, Rahni DO, Arnaout R, Lai M. The overuse of serum ceruloplasmin measurement. The American journal of medicine. 2013 Oct:126(10):926.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.01.039. Epub 2013 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 23953876]

European Association for Study of Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Wilson's disease. Journal of hepatology. 2012 Mar:56(3):671-85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22340672]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAlkhouri N, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Medici V. Wilson disease: a summary of the updated AASLD Practice Guidance. Hepatology communications. 2023 Jun 1:7(6):. doi: 10.1097/HC9.0000000000000150. Epub 2023 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 37184530]

Weiss KH, Thompson C, Dogterom P, Chiou YJ, Morley T, Jackson B, Amin N, Kamlin COF. Comparison of the Pharmacokinetic Profiles of Trientine Tetrahydrochloride and Trientine Dihydrochloride in Healthy Subjects. European journal of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics. 2021 Sep:46(5):665-675. doi: 10.1007/s13318-021-00704-1. Epub 2021 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 34357516]

Schilsky ML, Czlonkowska A, Zuin M, Cassiman D, Twardowschy C, Poujois A, Gondim FAA, Denk G, Cury RG, Ott P, Moore J, Ala A, D'Inca R, Couchonnal-Bedoya E, D'Hollander K, Dubois N, Kamlin COF, Weiss KH, CHELATE trial investigators. Trientine tetrahydrochloride versus penicillamine for maintenance therapy in Wilson disease (CHELATE): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. The lancet. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2022 Dec:7(12):1092-1102. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00270-9. Epub 2022 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 36183738]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWei R, Yang J, Cheng CW, Ho WI, Li N, Hu Y, Hong X, Fu J, Yang B, Liu Y, Jiang L, Lai WH, Au KW, Tsang WL, Tse YL, Ng KM, Esteban MA, Tse HF. CRISPR-targeted genome editing of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes for the treatment of Wilson's disease. JHEP reports : innovation in hepatology. 2022 Jan:4(1):100389. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100389. Epub 2021 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 34877514]

Mariño Z, Schilsky ML. Wilson Disease: Novel Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Seminars in liver disease. 2024 Nov 26:():. doi: 10.1055/a-2460-8999. Epub 2024 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 39496313]

Nazer H, Ede RJ, Mowat AP, Williams R. Wilson's disease: clinical presentation and use of prognostic index. Gut. 1986 Nov:27(11):1377-81 [PubMed PMID: 3792921]

Dhawan A, Taylor RM, Cheeseman P, De Silva P, Katsiyiannakis L, Mieli-Vergani G. Wilson's disease in children: 37-year experience and revised King's score for liver transplantation. Liver transplantation : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society. 2005 Apr:11(4):441-8 [PubMed PMID: 15776453]

Gow PJ, Smallwood RA, Angus PW, Smith AL, Wall AJ, Sewell RB. Diagnosis of Wilson's disease: an experience over three decades. Gut. 2000 Mar:46(3):415-9 [PubMed PMID: 10673307]

Yoshitoshi EY, Takada Y, Oike F, Sakamoto S, Ogawa K, Kanazawa H, Ogura Y, Okamoto S, Haga H, Ueda M, Egawa H, Kasahara M, Tanaka K, Uemoto S. Long-term outcomes for 32 cases of Wilson's disease after living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2009 Jan 27:87(2):261-7. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181919984. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19155982]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLitwin T, Bembenek J, Antos A, Przybyłkowski A, Skowrońska M, Kurkowska-Jastrzębska I, Członkowska A. Liver transplantation as a treatment for Wilson's disease with neurological presentation: a systematic literature review. Acta neurologica Belgica. 2022 Apr:122(2):505-518. doi: 10.1007/s13760-022-01872-w. Epub 2022 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 35080708]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence