Introduction

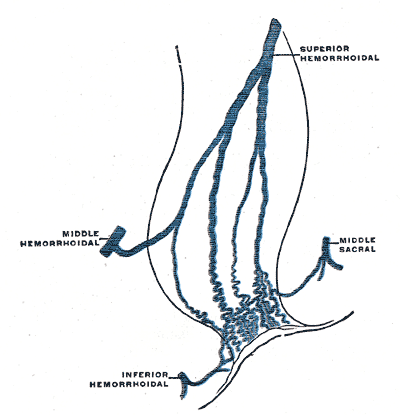

Hemorrhoidal disease is a common disorder requiring surgical intervention in approximately 10% of cases.[1] The prevalence is unknown because asymptomatic patients are less likely to seek medical help. About 4.4% of individuals in the United States exhibit symptoms, and those between 45 and 65 are most significantly impacted.[2][3][4] Hemorrhoids, found within the anal submucosa, are columns of vascular connective tissue that assist in maintaining continence and bulk to the anal canal. Although the pathophysiology of hemorrhoids is not fully understood, one theory suggests that they may develop due to varicose veins in the anal canal. However, this concept is generally not well established. Many experts firmly believe the root cause of hemorrhoids is the deterioration or degradation of vascular cushions rather than any other potential factor.[5] See Image. Hemorrhoidal and Middle Sacral Veins.

The 3 primary hemorrhoidal columns are in the left lateral, right anterolateral, and right posterolateral positions of the anal canal. The hemorrhoids can be internal or external based on their location relative to the dentate line.[3] Internal hemorrhoids can be further graded from I to IV based on the degree of prolapse, guiding the treatment options.[2] Patients presenting with symptomatic internal hemorrhoids complain of painless, bright red bleeding, described as streaks of blood in the stool, anal itching, pain, worrisome grape-like tissue prolapse, or a combination of these symptoms. External hemorrhoids are asymptomatic in most patients except for thrombosed external hemorrhoids, which cause significant pain due to their innervation by somatic nerves.[2][4]

Conducting a comprehensive history and physical examination specific to the disease is important, focusing on assessing the severity and duration of symptoms and identifying any relevant risk factors. Hemorrhoids can be treated with medical and surgical interventions depending on their degree of prolapse and whether they are internal or external. Hemorrhoids can undergo treatment with both medical or surgical interventions depending on the degree of prolapse and their locations.[6] One of the first and foremost conservative recommendations is a high-fiber diet. Garg recommends adding 4 to 5 teaspoons of fiber daily, corresponding to 20 to 25 g of supplemental fiber. For this method to be effective and not cause abdominal cramping, an adequate amount of water (500 mL) must be consumed simultaneously with the fiber supplement to absorb the water and result in soft stools. This intervention has proven to stop progression and help decrease the size of prolapse.[7]

Rubber band ligation and infrared coagulation are indicated for grade 1 and 2 hemorrhoids that fail medical management.[8] The reported number of rubber banding sessions is 1, occasionally 2, with a waiting period of 4 weeks between visits.[9] When comparing the 2, long-term success favors rubber banding, whereas infrared coagulation is associated with less pain, likely due to lack of mucopexy during the procedure. The failure rate for rubber band ligation is 4 times less than that seen in infrared coagulation.[2] Surgical excision is the most effective treatment for recurrent, symptomatic grade III or IV hemorrhoids. Surgical procedures primarily include closed, also called Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy, the most common technique in the United States, or the open, also called Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy, used in the United Kingdom and Europe.[2][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Hemorrhoids are cushions of nonpathological vascular tissue in the anal canal. Microscopically, they are described as sinusoids because they lack muscle, as do veins.[3] Anatomically, arteriovenous communications between vessels clarify why hemorrhoidal bleeding is bright red and has the same pH as arterial blood.[5][10]

The anal canal is roughly 4 cm long in adults, with the dentate line marking its midpoint. Internal hemorrhoids develop above the dentate line and are painless due to visceral innervation. They are covered by columnar epithelium and classified on the degree of prolapse. Prominent vessels and no prolapse characterize grade 1 hemorrhoids. Grade 2 hemorrhoids prolapse with Valsalva but spontaneously reduce. Grade 3 hemorrhoids also prolapse with Valsalva but need to be manually reduced. Grade 4 hemorrhoids are chronically prolapsed and cannot undergo manual reduction.[8] External hemorrhoids are covered in anoderm and are below the dentate line. Due to somatic nerve innervation, they are sensitive to touch, stretch, and temperature.[3] See Image. Hemorrhoids.

The grading system for physical findings in hemorrhoids is as follows:

- Grade I: Prominent hemorrhoidal vessels without prolapse

- Grade II: Prolapse occurs with the Valsalva maneuver and spontaneously reduces

- Grade III: Prolapse occurs with the Valsalva maneuver and requires manual reduction

- Grade IV: Prolapse is chronic and cannot be effectively reduced manually[2]

Indications

Operative hemorrhoidectomy is indicated for large third- and fourth-degree hemorrhoids in the following situations:

- Failed nonoperative management

- Advanced disease process unlikely to respond to conservative management

- Mixed hemorrhoids with a bulging external component

- Incarcerated internal hemorrhoids needing urgent intervention

- Coagulopathic patients requiring management of hemorrhoidal bleeding

Patients experiencing symptoms related to external hemorrhoids or a combination of internal and external hemorrhoids accompanied by prolapse are strongly recommended to undergo hemorrhoidectomy. The recommendation is based on high-quality evidence, including:

- Operative hemorrhoidectomy is indicated for patients who do not respond well to or cannot tolerate office-based procedures, including rubber-band ligation, sclerotherapy, and infrared coagulation.

- As discussed before, hemorrhoidectomy is also indicated in patients with grade III or IV hemorrhoids or significant accompanying skin tags; surgical hemorrhoidectomy remains an exceptionally effective approach.

- A meta-analysis of 18 randomized prospective studies comparing hemorrhoidectomy with office-based procedures demonstrated that hemorrhoidectomy was the most efficacious treatment for individuals with grade III hemorrhoids.[6]

Contraindications

Relative contraindications include the following:

- Patients unable to undergo general anesthesia due to medical comorbidities

- Baseline fecal incontinence

- Rectocele

- Presence of inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis

- Portal hypertension with rectal varices

- Uncontrolled bleeding disorder

Equipment

The main instrument used for an excisional hemorrhoidectomy is the scalpel, with or without scissors for dissection. Ligasure and Harmonic scalpels are modern-day energy devices used in the medical field over time. Ligasure is a bipolar cautery device used for both tissue division and coagulation of blood vessels. The Harmonic scalpel uses a reciprocating blade to generate tissue division and coagulation heat. The proposed benefits of using energy devices relative to their cost have not demonstrated significant clinical advantages.[3]

Monopolar electrocautery is a device capable of superior hemostasis compared to a scalpel. Excision of the hemorrhoidal complex without suture ligation is completed but at the expense of injuring adjacent tissues due to lateral thermal spread. A Hill Ferguson retractor is inserted into the anal canal to visualize the entire length of the hemorrhoidal complex.

Other equipment that is needed may include:

- DeBakey forceps

- Mayo scissors

- Large Kelly clamp

- Absorbable sutures

Personnel

The following personell are required for conducting a hemorrhoidectomy procedure:

- Operating surgeon

- First assistant

- Scrub technician

- Anesthesia team

Preparation

Bowel preparation is not mandatory; however, an enema may be necessary to clear the distal rectum. Prophylactic antibiotics are not required. Anesthetic selection should be individualized. The patient should receive counsel that spinal anesthesia carries an increased risk of urinary retention. A prone jack-knife position with the buttocks taped apart might be preferred to the lithotomy position.[8]

Technique or Treatment

Surgical hemorrhoidectomy is categorized as closed hemorrhoidectomy (Ferguson technique) or open hemorrhoidectomy (Milligan-Morgan). Milligan-Morgan is more commonly used in the United Kingdom and Europe. The Ferguson technique is the most common in the United States.

- The Hill Ferguson retractor is inserted in the anal canal to assess all 3 hemorrhoidal columns. The excision can be limited to only one column, but all 3 can be excised during the same operation if clinically indicated. The clinician should address the largest of the pathologic columns first.

- The enlarged column should be compressed at the base with DeBakey forceps to ensure the anoderm is tension-free. An elliptical incision is made around the hemorrhoidal column with a 10-scalpel blade.

- The pedicle is dissected off the surface of the internal anal sphincter using Mayo scissors up to the level of the pedicle. The pedicle is grasped with a large Kelly and is suture ligated with 3-0 Vicryl on a CT 2 needle.

- A deeper suture fixation of 3-0 Vicryl is used at the top of the anorectal ring to reduce the risk of recurrent prolapse. The suture is then used to close the rectal mucosa, anoderm, and perianal skin in a running fashion.

- In addition to these conventional techniques, stapled hemorrhoidopexy might be utilized. During this procedure, the hemorrhoidal columns are not excised but are lifted above the anal verge and attached. Studies show high rates of recurrence as well as microscopic incorporation of sphincter muscle in the resection specimens, which leads to transient flatus incontinence.[2][5][11]

- Based on moderate-quality evidence, patients undergoing surgical hemorrhoidectomy are strongly recommended to implement a multimodality pain regimen. This approach limits narcotic medication use and facilitates a quicker recovery.

Complications

Potential complications of hemorrhoidectomies can include the following:

- The patient should anticipate pain and anal fullness within the first week following hemorrhoidectomy and hemorrhoidopexy. Adequate pain control, as well as the use of stool softeners, are a priority in the postoperative period.

- Early complications include bleeding and urinary retention.

- Rare but life-threatening complications that must be recognized early include sepsis, abscess formation, and massive bleeding.[2]

- Late complications include anal stenosis, skin tags, recurrent hemorrhoids, delayed hemorrhage, and fecal incontinence.

- Complications following surgical hemorrhoidectomy are uncommon, but post-procedure hemorrhage is the most frequently reported complication, ranging from 1% to 2% in larger series.

- Acute urinary retention is observed in approximately 1% to 15% of cases and is the primary reason for a delayed discharge.

- Urinary retention rate increases after spinal anesthesia and procedures involving hemorrhoidal artery ligation. However, the risk can be minimized by reducing the volume of intravenous fluids administered and carefully administering local anesthesia.[12][13]

Clinical Significance

Hemorrhoidal columns are a normal part of anorectal anatomy and require symptomatic treatment. The first-line treatment includes conservative management, and the patient should be educated on fiber supplementation for adequate results.[3] Surgical excision is the preferred treatment method when medical management fails and the degree of prolapse advances. Success rates of removal are excellent, with low rates of recurrence. Open and closed techniques have similar rates of postoperative pain, need for analgesics, and complications.[8]

- Based on a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials involving 1326 patients, the closed hemorrhoidectomy approach was correlated with reduced postoperative pain, accelerated wound healing, and a lower incidence of postoperative bleeding.

- Open and closed hemorrhoidectomy procedures can be performed using various surgical devices. In a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials involving more than 1300 patients, the closed approach was associated with reduced postoperative pain, faster wound healing, and a lower risk of postoperative bleeding.

- Furthermore, open and closed approaches had similar postoperative complications, hemorrhoid recurrence, and infectious complications.

- Another meta-analysis of 5 studies, including more than 300 patients, indicated that closed hemorrhoidectomy with bipolar energy resulted in faster procedures, less postoperative pain, and comparable rates of postoperative complications.

- Similarly, in a meta-analysis of 8 studies, ultrasonic shears during hemorrhoidectomy led to an earlier return to work, decreased postoperative pain, and fewer postoperative complications than conventional techniques.

- Interestingly, a randomized controlled trial comparing the 2 devices during closed hemorrhoidectomy found similar postoperative pain scores and clinical outcomes. However, further research is required to define their optimal use in operative interventions, particularly addressing the increased cost associated with these surgical modalities.

- In a comprehensive review of over 115,000 patients undergoing various surgical procedures, post-hemorrhoidectomy pain ranked in the 20s out of 529 distinct surgical procedures in terms of reported discomfort.

- Several surgical and postoperative management modifications have been explored to alleviate postoperative pain. For instance, topical 2% Diltiazem ointment has been demonstrated to reduce the need for narcotic medications and pain scores following conventional hemorrhoidectomy. Additionally, a meta-analysis involving 12 trials and 1095 patients undergoing excisional hemorrhoidectomy revealed significant pain reduction and an earlier return to routine activities in patients treated with topical nitroglycerin compared to the control group.

- Surgical sphincterotomy (LIS) is effective in reducing postoperative pain and the requirement for analgesics after excisional hemorrhoidectomy. Moreover, LIS has shown promise in decreasing the incidence of postoperative urinary retention and anal stenosis. However, the addition of LIS to excisional hemorrhoidectomy does carry the risk of minor anal leakage, albeit often temporary.

- Three randomized controlled trials have investigated the use of botulinum toxin A after hemorrhoidectomy, revealing a reduction in postoperative pain for less than one week following excisional hemorrhoidectomy. The adverse effects of botulinum toxin A, including incontinence to flatus, were comparable to placebo.

- The efficacy of oral metronidazole in controlling postoperative pain was evaluated in a recent meta-analysis, which found no significant improvement compared to placebo.

- Liposomal bupivacaine (LB) has been studied in 2 trials. The first study randomly assigned 189 patients undergoing excisional hemorrhoidectomy to LB or placebo. Pain intensity scores were significantly lower in the LB group, and a higher proportion of patients remained opioid-free for up to 3 days after surgery than in the placebo group. Another study involving 100 patients compared a single dose of bupivacaine HCl with various doses of LB upon completion of hemorrhoidectomy. Cumulative pain scores were significantly lower with LB at each study dose, and LB resulted in lower total postoperative opioid consumption during the same period. The time to the first opioid use was also delayed in the LB group compared to the bupivacaine HCl group. Furthermore, opioid-related adverse events were significantly lower in the LB group.[14][15]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hemorrhoids are widespread in society, and while they are easy to diagnose, the treatment is not always satisfactory. The disorder is best addressed by an interprofessional team dedicated to anorectal conditions. All healthcare team members see patients with hemorrhoids in different settings, depending on the acuity and severity of the disease. Understanding the degree of prolapse of internal hemorrhoids helps the healthcare professional choose the adequate treatment and provide appropriate education. Correct diagnosis of an acutely thrombosed external hemorrhoid promptly leads to treatment, increasing overall patient safety and satisfaction.

Several vital clinical recommendations are published for practice:

- Increasing fiber intake is useful as a first-line medical treatment option.

- Grades 1 to 2 hemorrhoids can successfully be treated in an office setting with rubber band ligation.

- Excisional hemorrhoidectomy is only indicated for grade 3 or 4, recurrent or symptomatic hemorrhoidal disease.[2]

Patient education is vital because hemorrhoids are preventable. The nurse, dietitian, and pharmacist should encourage the patient to avoid constipation, drink ample water, be physically active, add fiber to the diet, and refrain from using too many pain medications (which cause constipation). The overall outcomes following surgery vary from good to poor. Residual pain and recurrence are not uncommon after almost every procedure. Interprofessional team management involving clinicians, nursing, and pharmacy can drive better patient outcomes.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The interprofessional team interventions for hemorrhoidectomy include the following:

- Ensure the patient has given written consent

- Educate the patient about the treatment of hemorrhoids

- Help with patient positioning and prepping during surgery

- Assist the surgeon with the procedure

- Explain postoperative care

- Educate the patient on how to perform sitz baths

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Interprofessional team monitoring for patients undergoing hemorrhoidectomy include:

- Monitor the patient during surgery

- Monitor the patient in the postoperative period

- Check for bleeding after surgery

- Assess the level of pain after surgery

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Hemorrhoidal and Middle Sacral Veins. The image shows the middle, inferior, and superior hemorrhoidal and middle sacral veins.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Guttadauro A, Maternini M, Chiarelli M, Lo Bianco G, Pecora N, Gabrielli F. Evolution in the surgical management of hemorrhoidal disease. Annali italiani di chirurgia. 2018:89():101-106 [PubMed PMID: 29848814]

Mott T, Latimer K, Edwards C. Hemorrhoids: Diagnosis and Treatment Options. American family physician. 2018 Feb 1:97(3):172-179 [PubMed PMID: 29431977]

Schubert MC, Sridhar S, Schade RR, Wexner SD. What every gastroenterologist needs to know about common anorectal disorders. World journal of gastroenterology. 2009 Jul 14:15(26):3201-9 [PubMed PMID: 19598294]

Lorenzo-Rivero S. Hemorrhoids: diagnosis and current management. The American surgeon. 2009 Aug:75(8):635-42 [PubMed PMID: 19725283]

Hardy A, Cohen CR. The acute management of haemorrhoids. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2014 Oct:96(7):508-11. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13946184900967. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25245728]

Sato S, Oga J, Shirahata A, Ishida Y. Clinical impact of a new method using a clear proctoscope to evaluate the therapeutic effect of sclerotherapy with aluminum potassium sulfate and tannic acid (ALTA) for internal hemorrhoids: a prospective cohort study. Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery. 2023 Jan 1:13(1):441-448. doi: 10.21037/qims-22-471. Epub 2022 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 36620149]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGarg P. Hemorrhoid Treatment Needs a Relook: More Room for Conservative Management Even in Advanced Grades of Hemorrhoids. The Indian journal of surgery. 2017 Dec:79(6):578-579. doi: 10.1007/s12262-017-1664-5. Epub 2017 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 29217916]

Rakinic J. Benign Anorectal Surgery: Management. Advances in surgery. 2018 Sep:52(1):179-204. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2018.04.004. Epub 2018 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 30098612]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCocorullo G, Tutino R, Falco N, Licari L, Orlando G, Fontana T, Raspanti C, Salamone G, Scerrino G, Gallo G, Trompetto M, Gulotta G. The non-surgical management for hemorrhoidal disease. A systematic review. Il Giornale di chirurgia. 2017 Jan-Feb:38(1):5-14 [PubMed PMID: 28460197]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAigner F, Gruber H, Conrad F, Eder J, Wedel T, Zelger B, Engelhardt V, Lametschwandtner A, Wienert V, Böhler U, Margreiter R, Fritsch H. Revised morphology and hemodynamics of the anorectal vascular plexus: impact on the course of hemorrhoidal disease. International journal of colorectal disease. 2009 Jan:24(1):105-13. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0572-3. Epub 2008 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 18766355]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSturiale A, Fabiani B, Menconi C, Cafaro D, Fusco F, Bellio G, Schiano di Visconte M, Naldini G. Long-term results after stapled hemorrhoidopexy: a survey study with mean follow-up of 12 years. Techniques in coloproctology. 2018 Sep:22(9):689-696. doi: 10.1007/s10151-018-1860-8. Epub 2018 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 30288629]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVinson-Bonnet B, Higuero T, Faucheron JL, Senejoux A, Pigot F, Siproudhis L. Ambulatory haemorrhoidal surgery: systematic literature review and qualitative analysis. International journal of colorectal disease. 2015 Apr:30(4):437-45. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-2073-x. Epub 2014 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 25427629]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceToyonaga T, Matsushima M, Sogawa N, Jiang SF, Matsumura N, Shimojima Y, Tanaka Y, Suzuki K, Masuda J, Tanaka M. Postoperative urinary retention after surgery for benign anorectal disease: potential risk factors and strategy for prevention. International journal of colorectal disease. 2006 Oct:21(7):676-82 [PubMed PMID: 16552523]

Haas E, Onel E, Miller H, Ragupathi M, White PF. A double-blind, randomized, active-controlled study for post-hemorrhoidectomy pain management with liposome bupivacaine, a novel local analgesic formulation. The American surgeon. 2012 May:78(5):574-81 [PubMed PMID: 22546131]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGorfine SR, Onel E, Patou G, Krivokapic ZV. Bupivacaine extended-release liposome injection for prolonged postsurgical analgesia in patients undergoing hemorrhoidectomy: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2011 Dec:54(12):1552-9. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318232d4c1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22067185]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence