Introduction

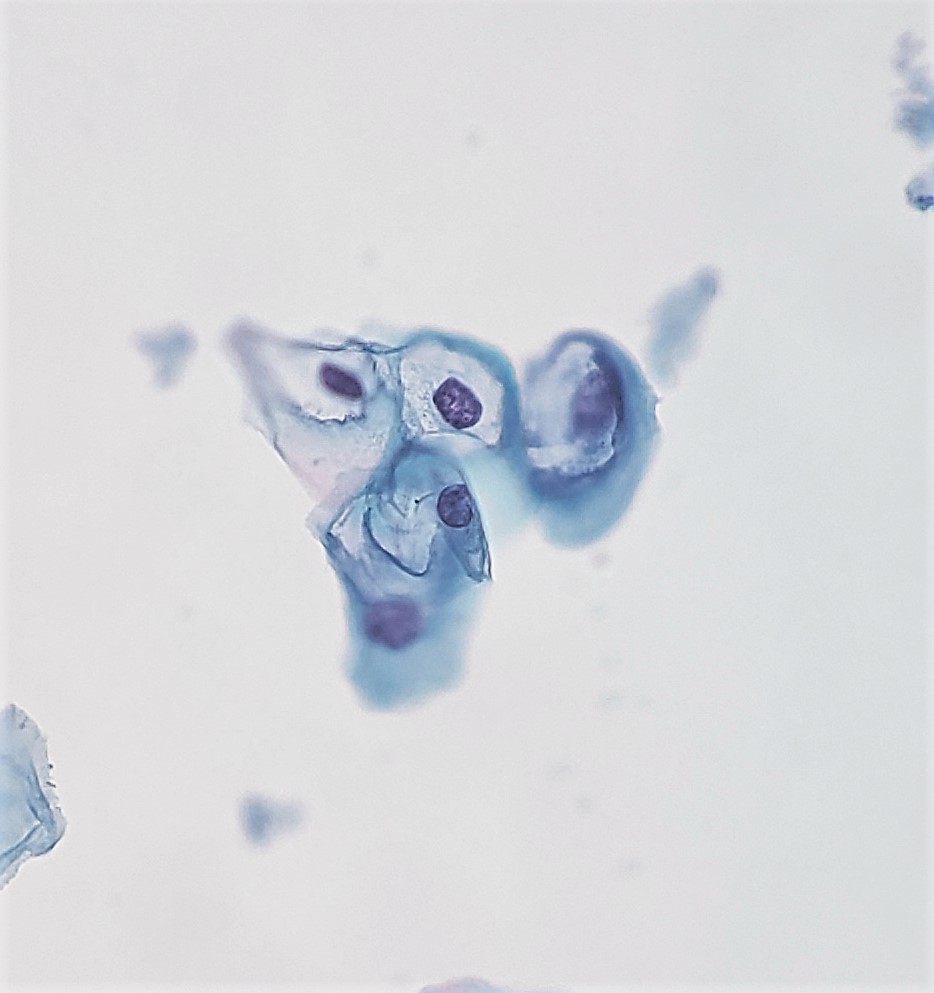

Koilocytosis is a descriptive term derived from the Greek adjective koilos, meaning hollow. Koilocytosis is pathognomonic, though not required, for the diagnosis of low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL). Koilocytes are squamous epithelial cells with perinuclear cavitation and nuclear features of LSIL, to include nuclear enlargement, coarse chromatin, and irregular nuclear membranes. A rim of condensed cytoplasm often surrounds the perinuclear cavitation, giving the cell a "halo" or cleared-out appearance around the dysplastic nucleus. Researchers and pathologists have identified koilocytic cells in epithelium throughout the body, but the initial description came from cervical samples.[1] Cervical koilocytosis has since formed the basis for much of the research surrounding koilocytes, including their etiology and significance.[2]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Koilocytosis describes the culmination of specific cellular events caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV).[3] Koilocytes are thus indicative of and specific for HPV infection.[4] HPV induces the transformation of cells and is associated with malignant entities, such as certain carcinomas of the cervix, oral cavity, and larynx.[5][6] HPV is also associated with benign entities such as condylomata, commonly known as genital warts.[7][8]

Causes

HPV Transmission occurs through direct contact of skin or mucosal membranes, and commonly, the virus is sexually transmitted. It infects the immature basal cells of the squamous epithelium. When immature basal cells do not have the protective cover of more mature cells, they are vulnerable to infection. Exposure of the immature basal cells can occur through metaplastic processes, i.e., the transition zone of the cervix, or through external insults resulting in mucosal or epithelial injury. Once a virus infects a basal cell, it then replicates in the maturing squamous cells and can cause the cleared-out cytoplasm and nuclear changes characteristic of koilocytes.[7][3]

Anatomical Pathology

Koilocytes are not visible grossly, but they are visible microscopically. The anogenital and oropharyngeal regions are the main areas of the body that harbor koilocytes.[2][9][8] Cervical cytology specimens, also known as Pap smears, commonly show koilocytosis.[3] Koilocytes are less commonly encountered in urine cytology specimens and infrequently in anal cytology.[10][9] With the Papanicolaou stain, the condensed cytoplasm can be pink, blue, or both. The cytoplasmic perinuclear cavitation is nearly transparent, but may occasionally contain a few condensed cytoplasmic granules. The nucleus is hyperchromatic with an irregular border and enlarged to at least three times the size of an intermediate squamous cell nucleus. Some cells may exhibit binucleation.[11]

With the hematoxylin and eosin stain of fixed tissue, the findings are very similar. The pink cytoplasm condenses around conspicuous perinuclear cavitation, and the enlarged nucleus exhibits hyperchromasia and membrane irregularity.[12] Maturing squamous cells, those found in the superficial or intermediate layers, exhibit the koilocytic changes.[3][13] Basilar squamous cells may be infected, but they do not show the characteristics of koilocytes. Reactive squamous epithelium can exhibit cells that mimic koilocytes with a vacuolar appearance. Strict criteria for koilocytes, coupled with the context of the surrounding tissue, can aid in the proper classification.[14]

Electron microscopy, a specialized modality of anatomic pathology, can also contribute to the identification of koilocytes by revealing viral particles within the nucleus.[15][16]

Clinical Pathology

Koilocytosis is a description used in anatomic pathology, but it may involve clinical pathology by prompting HPV DNA testing.[17] The analysis uses molecular biology techniques, including nucleic acid hybridization, nucleic acid amplification, and signal amplification to type HPV. Many laboratories use polymerase chain reaction techniques for this purpose.[2][18] The addition of more objective diagnostic data points is particularly crucial, given the suboptimal interobserver reliability in the identification of koilocytes.[19]

Biochemical and Genetic Pathology

Koilocytosis is part of a precancerous pathway in cervical specimens.[20] Therefore, identification of koilocytosis may prompt additional testing to identify the HPV type involved. The types of HPV are categorized as low- or high-risk, referring to their oncogenicity. If an HPV type has been isolated from cancer, it is generally categorized as high-risk.[7]

Mechanisms

HPV is a non-enveloped DNA virus with a circular double-stranded DNA. After infection of a basal cell, HPV transcribes one of its two DNA strands, thus leading to viral protein formation. Two proteins, E6 and E7, are responsible for the oncogenic effects of the virus. They interrupt normal cell death pathways and promote cellular proliferation by interfering with the tumor suppressor genes RB and p53. If the virus incorporates its DNA into the genome (integrated viral DNA), it replicates in the maturing squamous cells. The koilocytic morphology results from E4 protein, which acts to disrupt the cytoskeleton of the squamous cell.[3] Krawczyk et al. suggest that HPV proteins E5 and E6 work together to promote the formation and fusion of perinuclear cavitations. This fusion likely creates the large cavitation that distinguishes HPV-infected cells by giving them their cleared-out appearance.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Koilocytosis more likely occurs in certain demographic groups and anatomic locations due to the frequent sexual transmission of HPV. Although, other transmission modes are possible, such as a vertical transmission from mother to infant.[21] Researchers have even identified HPV DNA in breast milk.[22]

Koilocytosis is not visible on physical exam, but colposcopy may reveal lesions that exhibit koilocytosis microscopically on subsequent biopsy. The correlation between HPV type and colposcopic appearance is an area of research.[20]

Clinical Significance

Koilocytosis and its significance vary between organ systems. Koilocytosis reveals HPV infection, which is often transient. The immune system clears most HPV infections within 18 months.[7] Persistent infection, however, is associated with various cancers, particularly cervical cancer. Many professional organizations recommend HPV testing of cervical specimens since HPV is the causative agent of cervical cancer.[2] The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology incorporated HPV testing into its algorithms for screening tests stratified by age. In women over 30 years of age, HPV co-testing is necessary regardless of the diagnosis; many of these women will have a diagnosis of LSIL in a cervical specimen. About half of LSILs regress, but those lesions associated with high-risk HPV may progress to cancer more frequently.[17] High-risk HPV types 16 and 18 are most commonly associated with cervical cancer.[9][20] The carcinogenic effects of HPV, especially in relation to cervical cancer, led to the development of HPV vaccines.[2]

In certain cancers of the head and neck, HPV testing has prognostic significance, but the diagnostic algorithm does not include the identification of koilocytes. Survival is better in patients with HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck compared to squamous cell carcinoma that is not HPV-associated.[8]

Anal cancers are frequently associated with HPV, and anal cytology specimens undergo evaluation in much the same manner as cervical Pap smears. Koilocytes are not a frequent finding, but they are diagnostic of LSIL in this anatomic location as well.[9]

In penile cancer, the absence of koilocytosis may predict lymph node metastasis.[23] Koilocytosis in penile and breast cancers otherwise has no known meaning beyond HPV infection.[24][22][4]

As research continues, the role of koilocytosis in different organ systems may change. Currently, koilocytosis acts as a marker for HPV infection and may help direct further diagnostic decision-making.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Koss LG. The 57th birthday of koilocytes. Cancer cytopathology. 2012 Dec 25:120(6):421. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21231. Epub 2012 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 22927183]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhu Y, Wang Y, Hirschhorn J, Welsh KJ, Zhao Z, Davis MR, Feldman S. Human Papillomavirus and Its Testing Assays, Cervical Cancer Screening, and Vaccination. Advances in clinical chemistry. 2017:81():135-192. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2017.01.004. Epub 2017 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 28629588]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKrawczyk E, Suprynowicz FA, Liu X, Dai Y, Hartmann DP, Hanover J, Schlegel R. Koilocytosis: a cooperative interaction between the human papillomavirus E5 and E6 oncoproteins. The American journal of pathology. 2008 Sep:173(3):682-8. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080280. Epub 2008 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 18688031]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLawson JS, Glenn WK, Heng B, Ye Y, Tran B, Lutze-Mann L, Whitaker NJ. Koilocytes indicate a role for human papilloma virus in breast cancer. British journal of cancer. 2009 Oct 20:101(8):1351-6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605328. Epub 2009 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 19773762]

Syrjänen KJ. Two Landmark Studies Published in 1976/1977 Paved the Way for the Recognition of Human Papillomavirus as the Major Cause of the Global Cancer Burden. Acta cytologica. 2017:61(4-5):316-337. doi: 10.1159/000477372. Epub 2017 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 28693008]

Orita Y, Gion Y, Tachibana T, Ikegami K, Marunaka H, Makihara S, Yamashita Y, Miki K, Makino T, Akisada N, Akagi Y, Kimura M, Yoshino T, Nishizaki K, Sato Y. Laryngeal squamous cell papilloma is highly associated with human papillomavirus. Japanese journal of clinical oncology. 2018 Apr 1:48(4):350-355. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyy009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29447361]

Groves IJ, Coleman N. Pathogenesis of human papillomavirus-associated mucosal disease. The Journal of pathology. 2015 Mar:235(4):527-38. doi: 10.1002/path.4496. Epub 2015 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 25604863]

Syrjänen S, Rautava J, Syrjänen K. HPV in Head and Neck Cancer-30 Years of History. Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. Progres dans les recherches sur le cancer. 2017:206():3-25 [PubMed PMID: 27699526]

Bean SM, Chhieng DC. Anal-rectal cytology: a review. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2010 Jul:38(7):538-46. doi: 10.1002/dc.21242. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19941374]

Aggarwal S, Arora VK, Gupta S, Singh N, Bhatia A. Koilocytosis: correlations with high-risk HPV and its comparison on tissue sections and cytology, urothelial carcinoma. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2009 Mar:37(3):174-7. doi: 10.1002/dc.20978. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19170170]

Meisels A, Fortin R. Condylomatous lesions of the cervix and vagina. I. Cytologic patterns. Acta cytologica. 1976 Nov-Dec:20(6):505-9 [PubMed PMID: 1069445]

Fletcher S. Histopathology of papilloma virus infection of the cervix uteri: the history, taxonomy, nomenclature and reporting of koilocytic dysplasias. Journal of clinical pathology. 1983 Jun:36(6):616-24 [PubMed PMID: 6304149]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePurola E, Savia E. Cytology of gynecologic condyloma acuminatum. Acta cytologica. 1977 Jan-Feb:21(1):26-31 [PubMed PMID: 264754]

Pinto AP, Crum CP, Hirsch MS. MOLECULAR MARKERS OF EARLY CERVICAL NEOPLASIA. Diagnostic histopathology (Oxford, England). 2010 Oct 1:16(10):445-454 [PubMed PMID: 21076641]

Sato S, Chiba H, Shikano K, Horiguchi M, Wada Y, Yajima A, Okagaki T. [Ultrastructural observation of human papillomavirus particles in the uterine cervix intraepithelial neoplasia]. Gan no rinsho. Japan journal of cancer clinics. 1988 Jul:34(8):993-1000 [PubMed PMID: 2841511]

Toki T, Oikawa N, Tase T, Sato S, Wada Y, Yajima A, Higashiiwai H. Immunohistochemical and electron microscopic demonstration of human papillomavirus in dysplasia of the uterine cervix. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine. 1986 Jun:149(2):163-7 [PubMed PMID: 3018963]

Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, Garcia FA, Moriarty AT, Waxman AG, Wilbur DC, Wentzensen N, Downs LS Jr, Spitzer M, Moscicki AB, Franco EL, Stoler MH, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Myers ER, ACS-ASCCP-ASCP Cervical Cancer Guideline Committee. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2012 May-Jun:62(3):147-72. doi: 10.3322/caac.21139. Epub 2012 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 22422631]

Abreu AL, Souza RP, Gimenes F, Consolaro ME. A review of methods for detect human Papillomavirus infection. Virology journal. 2012 Nov 6:9():262. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-262. Epub 2012 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 23131123]

Kruse AJ, Baak JP, Helliesen T, Kjellevold KH, Robboy SJ. Prognostic value and reproducibility of koilocytosis in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. 2003 Jul:22(3):236-9 [PubMed PMID: 12819389]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJeronimo J, Massad LS, Schiffman M, National Institutes of Health/American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (NIH/ASCCP) Research Group. Visual appearance of the uterine cervix: correlation with human papillomavirus detection and type. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007 Jul:197(1):47.e1-8 [PubMed PMID: 17618753]

Rintala MA, Grénman SE, Puranen MH, Isolauri E, Ekblad U, Kero PO, Syrjänen SM. Transmission of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) between parents and infant: a prospective study of HPV in families in Finland. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2005 Jan:43(1):376-81 [PubMed PMID: 15634997]

Sandstrom RE. Regarding: Koilocytes indicate a role for human papilloma virus in breast cancer. British journal of cancer. 2010 Feb 16:102(4):786-7; author reply 788. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605549. Epub 2010 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 20125157]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNascimento ADMTD, Pinho JD, Júnior AALT, Larges JS, Soares FM, Calixto JRR, Coelho RWP, Belfort MRC, Nogueira LR, da Cunha IW, Silva GEB. Angiolymphatic invasion and absence of koilocytosis predict lymph node metastasis in penile cancer patients and might justify prophylactic lymphadenectomy. Medicine. 2020 Feb:99(9):e19128. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019128. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32118716]

Takamoto D, Kawahara T, Kasuga J, Sasaki T, Yao M, Yumura Y, Uemura H. The analysis of human papillomavirus DNA in penile cancer tissue by in situ hybridization. Oncology letters. 2018 May:15(5):8102-8106. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8351. Epub 2018 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 29731917]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence