Vaginal Foreign Body Evaluation and Treatment

Vaginal Foreign Body Evaluation and Treatment

Introduction

Vaginal foreign bodies present in female patients of all ages and a wide range of healthcare settings, including the emergency department, primary care office, gynecology office, and urology office. The objects found differ among age groups. Toys, tissue paper, and household objects are the most common in pediatrics. In adult women, considerations include tampons, condoms, menstrual cups, and items used for sexual gratification. Elderly patients are at increased risk for retained medical devices such as pessaries.[1][2] Patient populations such as prisoners and drug traffickers may use the vaginal canal and uterus to hide illicit substances.[3][4] In postpartum patients with recurrent abdominal pain, pelvic abscess, bladder stones, irritable bladder, and retained surgical gauze merit consideration; however, this is an unusual complication due to patient safety initiatives involving the careful counting of surgical gauze and sponges during delivery.[5]

Patients may self-report a foreign body or may present with an array of symptoms, including pelvic pain, vaginal discharge, and vaginal bleeding. There is a broad differential diagnosis for these symptoms, including malignancy, sexually transmitted infections, candidal infections, and pregnancy. The most common presenting symptom in pediatric patients is vaginal bleeding or discharge.[6]

When evaluating a patient who suspects a vaginal foreign body, history should focus on the details surrounding the initial event; this includes timing, the suspected object, and symptoms of the abdomen, pelvis, and genitalia. History taking is imperative in all patient populations. Even in pediatric patients, the majority, 54% in one study, recall the event.[6] It is essential to consider sexual abuse as a cause for foreign bodies, especially in the pediatric population.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The vagina is part of the female genitalia between the urethral meatus and anus. It is a muscular canal that serves as a connection between the external genitalia and the uterus. The vaginal opening has protection from the vulva, a structure comprised of the labia majora and labia minora. At the most proximal portion of the vagina is the cervix, a highly vascularized structure that guards the entrance to the uterus.

Indications

Evaluation for foreign bodies in the vaginal canal is necessary when patients present with a self-reported foreign body or complain of pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, or discharge. It should also be a consideration in patients with urinary and rectal complaints. In pre-pubertal patients with vaginal bleeding or persistent vaginal discharge despite antimicrobial treatment, imaging, and a gynecology referral for examination under anesthesia should be considered by primary care and emergency physicians.[7]

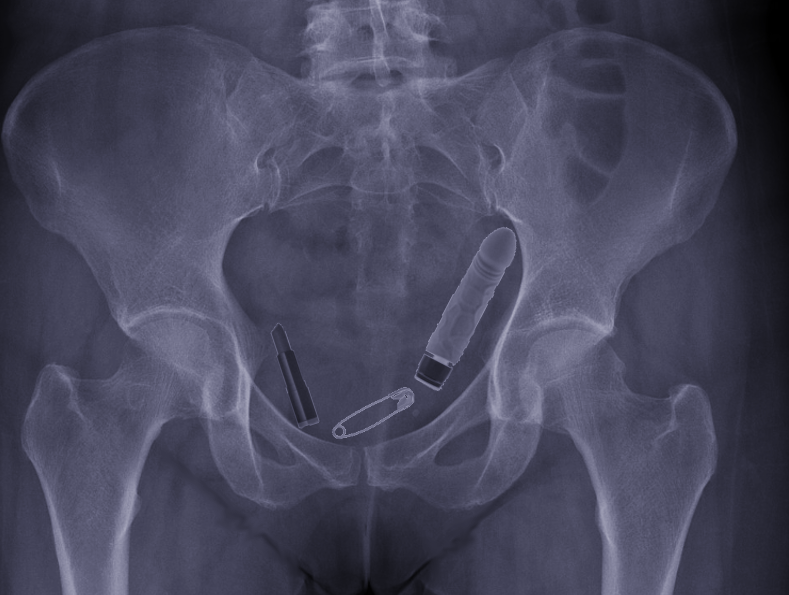

The examination includes a genital exam, which may include a pelvic exam with a speculum. Imaging is an option if the diagnosis is unclear or complications are suspected; this includes X-ray, CT scan, MRI, and ultrasound. The choice of imaging will vary based on presenting symptoms and patient age. Transabdominal ultrasound is the preferred modality in pediatric patients due to the lack of radiation, increased availability, and decreased level of invasiveness when compared to a transvaginal ultrasound. It has an overall sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 53%, which improves when the foreign body is over 5 mm in size. This percentage is significantly better than X-ray, which may only detect 23% of foreign bodies.[1] CT imaging is an option if complications such as fistula or abscess are suspected.

Contraindications

It is imperative to obtain consent before performing a pelvic examination. Examinations should not take place against patient wishes, as this can constitute assault. In pediatric patients or mentally handicapped patients, consent is necessary from their legal guardians. In these patients, an obstetrics and gynecology consult can be considered to perform an exam under sedation if there is a concern for patient distress. The majority of pediatric patients are manageable with same-day surgery.[8]

The clinician should not perform a pelvic exam if there is suspicion of rape or assault if the patient or guardian has any desire to press charges. In this case, defer the pelvic exam to a specialized investigation team, as introducing anything into the vulva or vagina, even sterile lubrication, can interfere with specimen collection. This approach is a critical consideration in the pediatric population if there is any suspicion for physical or sexual abuse.

Equipment

Several modalities are useful for assessment of the presence of a foreign body in the vagina, including a pelvic exam with or without anesthesia, ultrasonography, pelvic radiography, MRI, and vaginoscopy.[1] Many foreign bodies can be removed with forceps under direct visualization, though those in place for an extended period may require surgical intervention by a gynecologist.

Persistent discharge despite antimicrobial treatment should raise suspicion of a foreign body, and evaluation should take place.[7] It should also remain in the differential for pre-pubertal patients with vaginal bleeding despite a negative ultrasound. Additional radiographic imaging, ultrasonographic imaging, or examination under anesthesia may be required to rule out a foreign body.[9]

Extreme cases may require surgical intervention to remove foreign objects due to size, position, location, and other complicating factors. General anesthesia may be used to allow for full muscle relaxation and aid in foreign body removal.

Personnel

Genital evaluation should be performed with a member of the health care team at the bedside to act as a chaperone. This may occur in an outpatient office or in the Emergency Department. It is important to ask the patient if she prefers to have a female chaperone and to consider having at least one female staff member in the room during the examination. This health care team member, if qualified, can also act as an assistant during the pelvic exam by handing equipment to the provider performing the exam.

In pediatric patients, sedation in the operating room may be considered. In these cases, the usual operating staff, including an anesthesiologist and gynecologist, are necessary.

If ultrasonography is used to evaluate for a foreign body, an ultrasound technician may be required to perform a transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound.

Preparation

For routine examination in adult patients, preparation for pelvic exams includes asking the patient to remove her lower garments and providing a gown and drape. Privacy is necessary during this step, and a chaperone during the exam is paramount. It is vital that the patient feels comfortable and non-threatened. A non-sterile, lubricated speculum is usable in non-pregnant patients, and a reliable light source should be used to enhance visibility. Culture swabs should be readily available at the bedside if vaginal discharge is reported or appreciated on an exam as foreign bodies are a nidus for infection. Forceps can be brought to the bedside to aid in the removal of foreign material.

Complications

Retained vaginal foreign bodies pose risks. Indwelling foreign objects are niduses for infection; pelvic inflammation can result in infertility.[10] Additionally, compression on surrounding tissues can compromise blood flow resulting in necrosis, a complication that can pose its own sequela, including perforation and fistulas.[10][11] Rectovaginal and vesicovaginal fistulas often occur after foreign bodies have been in place for years. These include medically placed devices such as pessaries and fractured ring IUDs in addition to materials placed by patients. These patients may present with atypical symptoms, including frequent urinary tract infections, vesicle stones, vaginal bleeding, and rectal discharge or bleeding.[12][13][14][15]

Ulceration can also occur, especially if caustic objects are present in the vaginal vault, such as batteries.[10] There are also documented cases of vaginal stenosis after the complete embedding of a foreign object the patient has retained for several years.[10] In extreme cases, chronic inflammation of the surrounding tissue induced by retained foreign bodies can cause carcinogenesis as a result of oxidative and nitrative stress.[16]

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is associated most commonly with super-absorbent tampons, but the literature also documents it from other vaginal foreign material such as menstrual cups.[17] It occurs in 0.03 to 0.05 per 100000 individuals and has an overall mortality of 8%. Patients present with fever, rash, desquamation, and sepsis.[18] While the foreign material in the vagina does not directly cause TSS, it acts as a cofactor. The development of TSS requires a lack of antibodies to neutralize toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 and the presence of Staphylococcus aureus in the vaginal flora.[19]

Sharp foreign bodies such as needles can migrate to the gastroenterological system, urologic system, and into the deep pelvis. All symptomatic patients with sharp foreign bodies should have a consultation with gynecology. In patients where removal is complicated, a stable needle can be managed conservatively with a close specialist follow-up.[8]

It is important to note that foreign bodies are a potential cause of infection in all ages. Infection should be on the differential, especially in patients with systemic symptoms, including fever and or tachycardia.

Clinical Significance

Retained vaginal foreign bodies are clinically significant, especially considering the risks that they pose. Foreign bodies are a nidus for infection and may also result in ulceration, bleeding, and fistula formation. Care is necessary when evaluating patients believed to have retained vaginal foreign bodies, and these objects require removal to reduce the risk of complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Potential vaginal foreign body cases require an interprofessional effort, including the primary clinician, gynecology specialists, and nursing. Examination for vaginal foreign bodies requires questions about topics that may be sensitive to the patient. It is also important to note the personal aspect of a genital exam. Thus, extra steps are necessary for all personnel involved in the patient’s care. The patient should receive a gown and blanket, and the blanket should be used during the exam to cover anatomy that does not need to be exposed. Providers should speak to the patient openly and refrain from judgmental remarks. A welcoming environment between the providers and patients will enhance medical care by minimizing barriers. It is paramount that privacy is offered, including asking the patient if she would like her visitors to leave the room, and that a chaperone is present. A female nurse can fill the chaperone role, and other nursing duties are covered below. Interprofessional cooperation and teamwork are essential to successful outcomes in these cases. [Level 5]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

In patients who are awake during the examination, nursing staff should assess the patient throughout the exam for comfort. If sedation is used to perform any portion of the exam when evaluating for a foreign vaginal body, a nurse should monitor vital signs until the patient is awake and alert post-sedation.

Media

References

Yang X, Sun L, Ye J, Li X, Tao R. Ultrasonography in Detection of Vaginal Foreign Bodies in Girls: A Retrospective Study. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2017 Dec:30(6):620-625. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2017.06.008. Epub 2017 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 28669787]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAnderson J, Saleh HM, Paterek E. Flea Bites. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082162]

Abesamis MG, Taki N, Kaplan R. Uterine Body Stuffing Confirmed by Computed Tomography. Clinical practice and cases in emergency medicine. 2017 Nov:1(4):365-369. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.2017.5.33495. Epub 2017 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 29849377]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWankhade VK, Chikhalkar BG. Body packing and intra-vaginal body pushing of cocaine: A case report. Legal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2018 Mar:31():10-13. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2017.12.004. Epub 2017 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 29232651]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWu CC, Hsieh ML, Wang TM. Retained vaginal gauze with unusual complication: a case report. Changgeng yi xue za zhi. 1997 Mar:20(1):62-5 [PubMed PMID: 9178596]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStricker T, Navratil F, Sennhauser FH. Vaginal foreign bodies. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2004 Apr:40(4):205-7 [PubMed PMID: 15009550]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSmith YR, Berman DR, Quint EH. Premenarchal vaginal discharge: findings of procedures to rule out foreign bodies. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2002 Aug:15(4):227-30 [PubMed PMID: 12459229]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHe Y, Zhang W, Sun N, Feng G, Ni X, Song H. Experience of pediatric urogenital tract inserted objects: 10-year single-center study. Journal of pediatric urology. 2019 Oct:15(5):554.e1-554.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.05.038. Epub 2019 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 31301975]

Nayak S, Witchel SF, Sanfilippo JS. Vaginal foreign body: a delayed diagnosis. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2014 Dec:27(6):e127-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.10.006. Epub 2014 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 24656699]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNakib G, Calcaterra V, Pelizzo G. Longstanding Presence of a Vaginal Foreign Body (Battery): Severe Stenosis in a 13-Year-Old Girl. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2017 Feb:30(1):e15-e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2016.08.015. Epub 2016 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 27614288]

Lo TS, Jaili SB, Ibrahim R, Kao CC, Uy-Patrimonio MC. Ureterovaginal fistula: A complication of a vaginal foreign body. Taiwanese journal of obstetrics & gynecology. 2018 Feb:57(1):150-152. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2017.12.026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29458888]

Powers K, Grigorescu B, Lazarou G, Greston WM, Weber T. Neglected pessary causing a rectovaginal fistula: a case report. The Journal of reproductive medicine. 2008 Mar:53(3):235-7 [PubMed PMID: 18441734]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArias BE, Ridgeway B, Barber MD. Complications of neglected vaginal pessaries: case presentation and literature review. International urogynecology journal and pelvic floor dysfunction. 2008 Aug:19(8):1173-8. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0574-2. Epub 2008 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 18301852]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAndrikopoulou M, Lazarou G. Rare case of neglected pessary presenting with concealed vaginal hemorrhage. Female pelvic medicine & reconstructive surgery. 2015 Jan-Feb:21(1):e1-2. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000063. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25185620]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYan D, Shi Z, Wang L, Zhao X. Migration of a fractured ring IUD resulting in vesicovaginal fistula and vaginal calculus. The European journal of contraception & reproductive health care : the official journal of the European Society of Contraception. 2018 Oct:23(5):387-389. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2018.1517409. Epub 2018 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 30324812]

Osman K, Abdellaoui B, Weyl B, Levêque J. [Uterine Carcinosarcoma induced by a vaginal foreign body: a case report and review]. Journal de gynecologie, obstetrique et biologie de la reproduction. 2013 Feb:42(1):91-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2012.09.008. Epub 2012 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 23062745]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMitchell MA, Bisch S, Arntfield S, Hosseini-Moghaddam SM. A confirmed case of toxic shock syndrome associated with the use of a menstrual cup. The Canadian journal of infectious diseases & medical microbiology = Journal canadien des maladies infectieuses et de la microbiologie medicale. 2015 Jul-Aug:26(4):218-20 [PubMed PMID: 26361491]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBerger S, Kunerl A, Wasmuth S, Tierno P, Wagner K, Brügger J. Menstrual toxic shock syndrome: case report and systematic review of the literature. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2019 Sep:19(9):e313-e321. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30041-6. Epub 2019 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 31151811]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVostral S. Toxic shock syndrome, tampons and laboratory standard-setting. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2017 May 23:189(20):E726-E728. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.161479. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28536130]