Introduction

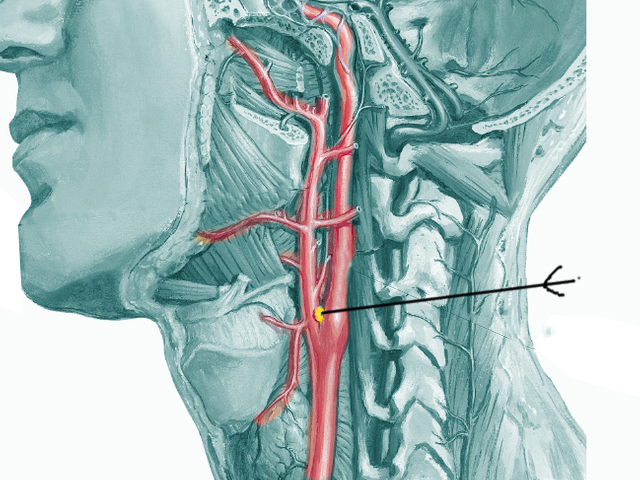

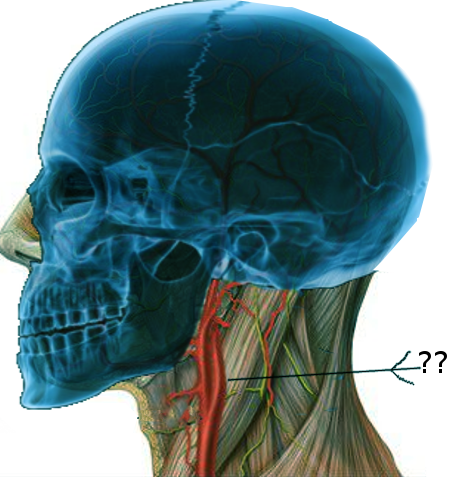

The carotid body is a 2 to 6 mm, round bilateral sensory organ in the peripheral nervous system located in the adventitia of the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. These peripheral chemosensory cells play a vital, physiologic role in the human body as they maintain physiologic homeostasis and regulation of sustaining life. These sensory chemoreceptors act to detect chemical changes in the body through the interaction with surrounding arterial blood flow by monitoring blood gas tension and pH.[1] Specifically, the carotid bodies can detect changes in the quality in the composition of arterial blood flow, such as pH, CO2, temperature, and partial pressure of arterial oxygen.

The effect in which these structures play an essential physiologic role is in their physiologic response following changes in the vasculature by signaling the rest of the peripheral nervous system. The carotid bodies also possess an interdependent regulatory relationship with other regulatory organs, such as the kidney.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Anatomical Structure

The primary structure of the carotid body includes two main cell types: glomus type I cells and glomus type II, or sustentacular cells (De Castro’s epithelioid cells).[2] Structurally, the sustentacular cells are neuroglial cells that support the cells of the carotid body. Glomus cells resemble neurons and release a variety of neurotransmitters in response to a hypoxic stimulus. In a low oxygen state, the glomus cells of the carotid body become depolarized, and several excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters are released.[3] These cell types were first described in the 1960s through electron microscopic analysis to be rich in dense-core granules and synaptic vesicle-containing structures, which suggested an endocrine, neurologic function.[2] Later in the 1980s, it was discovered that glomus cells in the carotid body contained a vascular supply, arterio-venous anastomosis, and the capability of regulating blood flow.[2][4]

Function

The primary function of the carotid body is to fulfill a regulatory role as a chemoreceptor for oxygen levels with an impact on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems.[5] Located at the bifurcation of the internal and external carotid arteries, the primary functional role of the carotid body is the reflex adjustment capabilities in response to the components of arterial blood flow and physiologic oxygen sensor.[4][6] The chemical processes that the carotid bodies tend to respond to are physiologic states of hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis. In contrast, the carotid sinus is a functioning baroreceptor located at the proximal internal carotid artery. In these osmolar sensitive states, the glomus cells of the carotid body translate these chemical changes into electrical, biochemical changes to initiate a physiologic, regulatory response.[2]

Embryology

The embryological development of the carotid bodies is unique in origin. The common carotid arteries and the proximal internal carotid arteries derive from the third pharyngeal arch around the fourth and fifth weeks of gestation. The carotid body itself derives from both mesodermal components of the third branchial arch and neural elements from neural crest ectodermal origin.[7] These neural crest originating components include the type I cells, or glomus cells.[8]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The carotid body is an extremely vascular organ and receives vascular supply via the internal and external carotid arteries. Two types of capillary beds are responsible for the perfusion of the organ. Type I has capillaries that are large in diameter, fenestrated, and come in close contact with type I cells. The second type of capillary bed has vessels that are narrow, not fenestrated, surrounded by pericytes, and do not make close contact with type I or glomus cells. Blood exits the carotid body through the internal and external jugular veins.[8]

Nerves

Cell bodies of the afferent nerves of the carotid body lie in the petrosal ganglion. The sensory information from these nerves is relayed to the central nervous system via the carotid sinus branch of cranial nerve IX (glossopharyngeal nerve) and some via cranial nerve X (vagus nerve). The proximal axon of the afferent neurons terminates in the nucleus tractus solitarius in the brain stem where the respiratory neurons come together. Efferent innervation to the carotid body comes from the superior cervical ganglion; this modulates carotid body chemosensitivity through blood flow variation.[8]

Muscles

The surrounding musculature of the carotid arteries is clinically important. A thorough understanding of the associated anatomical relationship between the carotid vasculature and the muscles in the area may dictate surgical success. Discussion of surrounding muscles invites a description of the muscles of mastication. The four muscles of mastication include the temporalis, masseter, and medial and lateral pterygoid. These four muscles obtain their vascular supply from the facial artery and also the maxillary artery, both branches of the external carotid artery.[9]

The adjacent temporalis muscle receives its blood supply from the temporal artery. Other surrounding musculature includes the sternocleidomastoid muscle, trapezius, and scalene muscles. The sternocleidomastoid muscle has a dual arterial supply from the occipital artery and superior thyroid artery, both branches of the external carotid artery.[9] The trapezius has a triple blood supply, which includes the transverse cervical artery, dorsal scapular artery, and posterior intercostal arteries.[10]

Physiologic Variants

Common Carotid Artery Bifurcation Variance

The common carotid arteries usually bifurcate at the upper border of the thyroid cartilage. However, there are physiologic variants in specific individuals due to anatomical, genetic variations and also impact the success of certain surgical procedures to address disease states such as atherosclerosis.[11] In these cases, the variance of the location of the bifurcation of the common carotid artery could pose a surgical challenge in the setting of localized atherosclerosis where a distal bifurcation may be present.

Genetics

It is also important to note that carotid body tumors such as paragangliomas are frequently associated with a genetic mutation. This mutation is notably at the SDH gene. Interestingly, carotid body paragangliomas are also noted most frequently with populations who reside at higher altitudes.[12]

Surgical Considerations

Preoperative Embolization

Preoperative embolization is controversial in the surgical community. However, embolization aids in the gross total tumor removal, minimize bleeding intraoperatively, and decrease the incidence risk of paralysis of the cranial nerves.[12] The size and surrounding angiographic determine the decision for embolization.

Carotid Body Resection

Surgical manipulation of the neck can pose a risk to many vital structures, including resection of the carotid body. As the carotid body is an essential component of the reflexive ventilatory response during hypoxia, researchers have conducted studies to understand the response of the human body to carotid body resection. Bilateral local anesthesia or resection of the carotid bodies results in the absence of a reflexive respiratory response to hypoxia. Over time, however, extra-carotid chemoreceptors may begin to adapt, and the body once again regains the ventilatory reflex in response to hypoxia. This reflex can return in as little as 6 to 10 weeks after resection. The regained reflex is, however, reduced in comparison to that seen prior to resection.[8] Bipolar cautery is utilized frequently intraoperatively as well as the use of a microscope to assist in visualization of the carotid body and additionally for the benefit of decreasing intra-operative and post-operative complications.[12]

- Intraoperative Risks - In a carotid body, paraganglioma resection, cranial nerve paralysis, carotid artery disruption, and exsanguination are the risks that merit consideration.

- Surgical Planning - The first-line treatment for neck paragangliomas is surgical removal due to their 6 to 12% malignant potential.[12] Among the most important factors in surgical planning is the anatomical relationship to the internal carotid artery. Manipulation of this artery could be a life-threatening disruption, leading to rupture, thrombosis, stroke, or death. Adverse outcomes of intraoperative complications are said to rise significantly in patients who have already undergone an initial attempt for paraganglioma removal. Placement of an intra-arterial stent into the internal carotid artery has shown to provide more efficient facilitation of a carotid artery dissection and protection of the vasculature intraoperatively, minimizing potential life-threatening risks discussed above.[12] An important caveat to mention is that stent placement of the internal carotid artery is also associated with the necessity of lifelong antiplatelet therapy, which presents its own series of risks.

- Surgical Approaches

- Transcervical approach (TCA) - used for tumors of the lower parapharyngeal space (PPS)

- Transcervical-transparotid approach (TC-TPA)- used for tumors in the middle of the PPS

- Transcervical-transmastoid approach (TC-TMA)- used for tumors in the upper PPS that also have a posterior extension, with the removal of the mastoid tip

- Infratemporal fossa approach-type A (ITFA-A) - used for tumors in parts of the upper PPS that also have an extension to a vertical tract to the internal carotid artery; this includes a transposition of the facial nerve.

- Surgical Approaches

Clinical Significance

Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Studies on the ventilatory response in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) demonstrate that the carotid bodies respond differently in newly diagnosed patients when compared to patients with a long history of OSA. In newly diagnosed patients, the ventilatory response to hypoxia is augmented when compared to control subjects, which indicates that chemoreceptor sensitivity is higher in these patients and may be one of the causes of the sequelae of this disorder. The heightened sensitivity of chemoreceptors causes increased sympathetic drive leading to hypertension in patients with OSA. Additionally, research has shown that patients with sleep apneas that underwent glomectomy did not develop hypertension. This trend does not remain in patients with a long history of sleep apnea. After years of disordered breathing, the carotid body becomes desensitized to hypoxia leading to a depressed hypoxic ventilatory response. The reduced response to hypoxia seen in patients with long-standing OSA may explain the resting hypercapnia observed in these patients.[3]

Congestive Heart Failure

In congestive heart failure (CHF), similar to sleep-disordered breathing, patients exhibit an augmented ventilatory response to hypoxia. Patients with CHF also exhibit periodic breathing, increased sympathetic tone, and hypercapnia. Of clinical significance is the response to hyperoxia in these patients. Episodes of hyperoxia lead to breathing instability in patients with CHF because hyperoxia depresses carotid body activity. The mechanism of sensitization of the carotid body in CHF patients seems to be via the downregulation of nitric oxide synthases. Normally, nitric oxide works to inhibit carotid body activity.[3]

Hypertension

Hypertension causes similar effects on the carotid body, with increased sensitivity to hypoxia and an increased sympathetic tone. There is, however, a difference in the effect of hypertension on the carotid body depending on the type of hypertension. Essential hypertension leads to an augmentation of the carotid body response to hypoxia and increased sympathetic tone. Hypertension due to renal causes does not seem to impact the sensitivity of the carotid body. Studies evaluating the relative size of carotid bodies in hypertension have shown that carotid bodies are enlarged in essential hypertension but not in renal hypertension. Analysis of the effects of hypertension on catecholamines present in the carotid bodies has shown an increase in catecholamines within the carotid bodies in essential hypertension.[3]

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and the Hypoxic Disease States

The carotid body plays a regulatory role in an acute and chronic state of hypoxia. In the acute phase, the change in the partial pressure of oxygen detected by the glomus cells of the carotid body triggers the respiratory system to hyperventilate and diminish CO2 levels. The resulting respiratory alkalosis then triggers the kidneys to act as a buffer of the basic pH and retain bicarbonate. During physiologic states of chronic hypoxia and the physiologic acclimatization to high altitude, the glomus cells of the carotid body undergo hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the diminished insensitivity to hypoxic states.[1] This attenuated sensitivity to hypoxia in patients with COPD and another disease-related state of chronic hypoxia are postulated to contribute to their clinical deterioration.[1]

Carotid Body Response to High Altitude

The carotid bodies play an essential role in high-altitude ventilatory acclimatization; this refers to the increase in the respiratory rate at increasing altitudes. As an individual reaches higher altitudes, the oxygen content in the air decreases, leading to a hypoxic drive within the body. The carotid body is responsible for sensing this decrease in oxygen, and in turn, increasing the respiratory drive. Hyperplasia of glomus cells occurs after chronic hypoxia, which also points to the crucial role of the carotid bodies in acclimatization to high altitudes. Several things contribute to increased carotid body sensitivity during chronic hypoxia including, ionic changes in glomus cells, the release of second messengers, reduced dopaminergic inhibition of the carotid body, and increased levels of endothelin.[3]

Pregnancy

Pregnancy results in a prolonged physiological state of increased ventilation. Pregnant women also exhibit an augmented ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia. This increased sensitivity occurs after gestational week 20, which corresponds with increasing levels of progesterone and estradiol. Research shows that in non-pregnant women treated with progesterone and estrogen, there is an increased sensitivity to hypoxia. These findings suggest that there is a hormonal influence on the carotid body in pregnancy that leads to an increased ventilatory response to hypoxia.[8]

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS)

The pathogenesis of SIDS is suspected to involve the peripheral chemoreceptors or carotid bodies. SIDS is known to be the major cause of mortality in infants.[13] Studies have shown that the essential growth and development of these chemoreceptors occurs during the age range of less than one year, also a critical risk for SIDS. The suspicion is that hypoxia, prematurity, inflammation, and genetic factors, which are known risk factors for SIDS, also contribute to the functionality and developmental capabilities of central and peripheral chemoreceptors.[14] Specifically, the decrease in plasticity and neurochemical changes that occur in the carotid body may contribute to the pathogenesis of SIDS.[14] Since prematurity is a major risk factor, these infants have hyposensitivity and hypersensitivity impairments of their peripheral arterial chemoreceptors, which may provide a biologic explanation for this specific subset of patients who are predisposed to SIDS.[15] At the cellular level, the glomus cell tissue volume of the carotid body shows alterations in SIDS victims.[16] Exposure to tobacco smoke, substance abuse, and hypoxemic states affects the functionality of the carotid body, supporting the role that peripheral arterial chemoreceptors play a role in the development of SIDS.[16]

Carotid Sinus Syndrome

There was a case report of a 46-year-old woman who had symptoms associated with carotid sinus syndrome with associated episodes of syncope. With a 24-hour Holter monitor, the inference was that a pacemaker was indicated to prevent the syncopes associated with diagnostic findings of significant nocturnal cardiac pauses. After a cervical computed tomography scan, it revealed the patient to have a carotid body tumor, which was likely to have caused syncope and carotid sinus hypersensitivity.[17] After the removal of the carotid body tumor, the patient's symptoms resolved.

Paragangliomas of the Carotid Body

Paragangliomas are rare, hypervascular neoplasms that are usually benign and originate from the carotid body. Previously, these tumors were also referred to in the literature as carotid body tumors, glomus tumors, nonchromaffin tumors, and chemodectomas.[11] Most commonly found in women, this tumor arises from the paraganglionic cells in the carotid body and constitutes up to 6 to 70% of all head and neck paragangliomas. These tumors are said to be mostly benign, but 6-12.5% of cases have been shown to display features of malignancy.[7]

- Surgical consideration - These slow-growing neuroendocrine tumors pose a surgical challenge due to their close proximity to the internal and external carotid arteries, internal jugular veins, and lower cranial nerves.[12] The clinical importance of these tumors is of paramount importance since chemotherapy and radiation therapy are not possible treatments.

- Gross examination of carotid body paragangliomas - Gross specimens are usually interpreted by a pathologist as possessing the following characteristics: frequent areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, and iatrogenic artifacts.[12]

- Histopathologic interpretation of carotid body paragangliomas - Usually, paragangliomas appear well-circumscribed, often with a fibrous pseudocapsule. Rarely, there are areas of bone infiltration seen on histopathologic examination with frequent extensive areas of fibrosis. There are myelinated ganglionic structures that surround the tumor itself. On assessing the tumor cell morphology, the size of the tumor cells, reported by Prasad et al., is in a characteristic "zellballen" pattern, which describes a reticulated network of neuroepithelial sheets of varying thicknesses amidst rich, microvascular bedding.[12]

- Clinical aspects of paragangliomas - These rare neuroendocrine neoplasms are said to be invasive, yet indolent and sometimes go unnoticed in obese individuals. These tumors are described as pulsatile and have an average growth rate of 0.83 mm per year.[12] Carotid body tumors are rarely catecholamine secreting tumors, as in pheochromocytoma. However, if symptoms such as tachycardia and/or hypertension are present in a patient with a known paraganglioma or with such a family history, urinary catecholamine screening may be warranted. If the tumor enlarges medially, the swelling may impart a non-functional effect of cranial nerves IX, X, XII, which could result in clinical signs such as dysphagia, hoarseness, and foreign body sensation of the oropharynx.[12] If a tumor grows to involve the sympathetic chain, the clinical result could include ptosis, miosis, and anhydrosis.[12]

- Ine case report involved a 17-year-old girl who presented with a progressively increasing swelling in her neck for nine months. On examination, a 2 x 3 cm, firm, there was a pulsatile swelling felt in the left anterior triangle. The computed tomography (CT) scan of the mass was suggestive of a carotid body tumor, and urinary catecholamines were negative. The mass underwent complete excision.

Carotid Body as a Therapeutic Target

The known functional role of the carotid bodies as peripheral chemoreceptors is the ability to alter ventilatory response in states of hypoxia. However, newer studies show that the carotid bodies also act to detect changes and respond in a way that alters sympathetic tone in humans and may have potential therapeutic implications for diseases mediated by the sympathetic nervous system.[18] The consideration of deactivation of the carotid bodies as a novel therapeutic approach has already occurred in animal models.[19] In disease states with peripheral chemoreceptor oversensitivity such as hypertension and cardiac failure, the theory is that target carotid body regulation and deactivation may be a potential novel therapy. In human trials, the carotid body dissection appears to be an effective therapeutic option. However, only in a specific subset of patients: those who have had higher baseline hypersensitivity, a greater ventilatory frequency, and had a right side procedure.[20]

Media

References

Bee D, Howard P. The carotid body: a review of its anatomy, physiology and clinical importance. Monaldi archives for chest disease = Archivio Monaldi per le malattie del torace. 1993:48(1):48-53 [PubMed PMID: 8472064]

Fitzgerald RS, Eyzaguirre C, Zapata P. Fifty years of progress in carotid body physiology--invited article. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2009:648():19-28. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2259-2_2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19536461]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePrabhakar NR, Peng YJ. Peripheral chemoreceptors in health and disease. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2004 Jan:96(1):359-66 [PubMed PMID: 14660497]

Biscoe TJ. Carotid body: structure and function. Physiological reviews. 1971 Jul:51(3):437-95 [PubMed PMID: 4950075]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGrönblad M. Function and structure of the carotid body. Medical biology. 1983:61(5):229-48 [PubMed PMID: 6323893]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePrabhakar NR, Peng YJ. Oxygen Sensing by the Carotid Body: Past and Present. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2017:977():3-8. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-55231-6_1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28685420]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNaik SM, Shenoy AM, Nanjundappa, Halkud R, Chavan P, Sidappa K, Amritham U, Gupta S. Paragangliomas of the carotid body: current management protocols and review of literature. Indian journal of surgical oncology. 2013 Sep:4(3):305-12. doi: 10.1007/s13193-013-0249-4. Epub 2013 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 24426745]

Kumar P, Prabhakar NR. Peripheral chemoreceptors: function and plasticity of the carotid body. Comprehensive Physiology. 2012 Jan:2(1):141-219. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100069. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23728973]

Gofur EM, Al Khalili Y. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Internal Maxillary Arteries. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194441]

Yang D, Morris SF. Trapezius muscle: anatomic basis for flap design. Annals of plastic surgery. 1998 Jul:41(1):52-7 [PubMed PMID: 9678469]

Devadas D, Pillay M, Sukumaran TT. A cadaveric study on variations in branching pattern of external carotid artery. Anatomy & cell biology. 2018 Dec:51(4):225-231. doi: 10.5115/acb.2018.51.4.225. Epub 2018 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 30637155]

Mariani-Costantini R, Prasad SC, Paties CT, Pantalone MR, Mariani-Costantini R, Sanna M. Carotid Body and Vagal Paragangliomas: Epidemiology, Genetics, Clinicopathological Features, Imaging, and Surgical Management. Paraganglioma: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2019 Jul 2:(): [PubMed PMID: 31294944]

Menezes RG, Usman MS, Memon MM, Siddiqi TJ, Madadin M. Landmark publications on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: A bibliometrics analysis. Forensic science review. 2020 Jul:32(2):117-127 [PubMed PMID: 32712579]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePorzionato A, Macchi V, De Caro R. Central and peripheral chemoreceptors in sudden infant death syndrome. The Journal of physiology. 2018 Aug:596(15):3007-3019. doi: 10.1113/JP274355. Epub 2018 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 29645275]

Gauda EB, Cristofalo E, Nunez J. Peripheral arterial chemoreceptors and sudden infant death syndrome. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2007 Jul 1:157(1):162-70 [PubMed PMID: 17446144]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePorzionato A, Macchi V, Stecco C, De Caro R. The carotid body in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2013 Jan 1:185(1):194-201. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.05.013. Epub 2012 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 22613076]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceda Gama AD, Cabral GM. Carotid body tumor presenting with carotid sinus syndrome. Journal of vascular surgery. 2010 Dec:52(6):1668-70. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.07.016. Epub 2010 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 20864295]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTubek S, Niewiński P, Paleczny B, Langner A, Banasiak W, Ponikowski P. Human carotid bodies as a therapeutic target: new insights from a clinician's perspective. Kardiologia polska. 2018:76(10):1426-1433. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2018.0178. Epub 2018 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 30251240]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAbdala AP, McBryde FD, Marina N, Hendy EB, Engelman ZJ, Fudim M, Sobotka PA, Gourine AV, Paton JF. Hypertension is critically dependent on the carotid body input in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. The Journal of physiology. 2012 Sep 1:590(17):4269-77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.237800. Epub 2012 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 22687617]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNarkiewicz K, Ratcliffe LE, Hart EC, Briant LJ, Chrostowska M, Wolf J, Szyndler A, Hering D, Abdala AP, Manghat N, Burchell AE, Durant C, Lobo MD, Sobotka PA, Patel NK, Leiter JC, Engelman ZJ, Nightingale AK, Paton JF. Unilateral Carotid Body Resection in Resistant Hypertension: A Safety and Feasibility Trial. JACC. Basic to translational science. 2016 Aug:1(5):313-324 [PubMed PMID: 27766316]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence