Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Perineal Body

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Perineal Body

Introduction

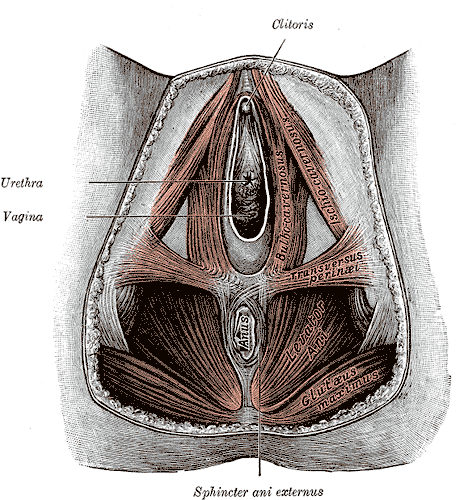

The perineal body, also referred to as the "central tendon of the perineum," is a fibromuscular structure located in the midline of the perineum (see Image. Female Perineum). The exact location of this structure is the midline at the junction of the anus and urogenital triangle in both female and male individuals. In the male body, the central tendon of the perineum is located between the anus and the bulb of the penis. In contrast, the female body has this structure lying between the anus and the posterior limit of the vulvar orifice.

The perineal body helps strengthen the pelvic floor and provides attachments to the following muscles:

- Bulbospongiosus: A striated muscle that adheres anterolaterally to the perineal body.

- Deep transverse perineal muscle: In the male body, this muscle adheres laterally to the perineal body.

- Compressor urethrae: In the female body, this muscle adheres anteriorly to the perineal body.

- External anal sphincter: Attaches posterolaterally to the perineal body.

- Internal anal sphincter: Intermingles with the longitudinal anis muscle (LAM) and adheres posteriorly to the perineal body.

- External urethral sphincter: Attaches anteriorly to the perineal body.

- Levator anis muscle: Comprises the internal fibers of the puborectalis muscle and adheres laterally to the perineal body along its whole vertical length.

- Rectourethralis: A perineal smooth muscle that runs from the LAM laterally to the bulbourethral glands and adheres anterolaterally to the puborectalis muscle.

- Longitudinal anis muscle: Known as the LAM and strongly attaches anteriorly and anterolaterally to the perineal body and the puborectalis muscle.[1]

Two fascial structures join the perineal body. The superficial perineal fascia and the perineal membrane join the perineal body anteriorly. The rectovaginal septum in female individuals joins the perineal body superiorly. The rectoprostatic septum in male individuals also attaches to the perineal body superiorly.[2]

The perineal body is critical for maintaining the integrity of the pelvic floor, especially in female persons. The perineal body may rupture during vaginal delivery, potentially widening the gap between the free borders of the levator muscles on both sides. Such a gap predisposes women to prolapse of the rectum, uterus, and, sometimes, the urinary bladder. The perineal body is also an important landmark during the surgical resection of anorectal tumors, ensuring the achievement of a tumor-free circumferential resection margin and reducing the risk of local recurrence.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The perineal body is the central fibrous skeleton of the perineum that has a pyramid shape in the male body and a wedge shape in the female body. Laterally, this structure consists of perineal smooth muscles, which represent the anterior continuity of the LAM. The perineum lies inferior to the pelvic diaphragm and comprises muscle-fascial structures that form a closure for the pelvis inferiorly. The perineal musculature differs embryologically from that of the pelvic diaphragm. The perineum receives innervation from motoneurons located in the nucleus of Onuf, transmitted through branches of the pudendal nerve. The perineal region extends from the skin to the inferior fascial surface of the pelvic floor and occupies a median position between the buttocks and the medial surface of the thighs.

The perineum is bounded anteriorly by the pubic arch and laterally extends in a posterior direction from the lower branch of the pubis and the ischium to the ischial tuberosity and the sacrotuberous ligament. Posteriorly, this region ends at the apex of the coccyx. The perineum has a rhomboid shape with a major axis directed anteroposteriorly.

A transverse line passing through the ischial tuberosities divides the perineum into 2 triangular regions. The posterior or anal triangle has its anterior base and apex at the coccyx. This region contains the terminal segment of the anal canal, the anal sphincters, the ischiorectal fossae, and the rectovaginal or prostate septum. The anterior or urogenital triangle has its posterior base and apex at the pubic symphysis. This region contains the external urogenital organs, the superficial perineal fascia, the anterior perineal muscles, and the sphincters.

The anterior and posterior triangles lie on different planes. The urogenital triangle is tilted downward and backward, while the anal triangle is tilted downward and forward. The line dividing the 2 triangles arises externally from the transverse muscles of the perineum. This line aligns with the ischial tuberosities laterally and intertwines the fibers in the middle, contributing to the formation of the perineal body. The posterior border of the superficial perineal fascia joins the perineal body. Superiorly, the superficial perineal fascia is attached to the rectovaginal or rectoprostatic septum, continuing upward to the arcus tendineus of the endopelvic fascia.[3]

Studies have confirmed the variability in describing the components of the perineal body and have acknowledged the challenges in dissecting this structure. These studies, which utilized thin-slice magnetic resonance imaging, reported that the perineal body consisted of the bulbospongiosus muscle, the superficial transverse perineal muscle, the internal and external anal sphincters, the puboperinealis, and the puboanalis portions of the puborectalis muscle.[4]

The perineal body is the space where the connective tissue of muscles and septa converge. This structure is the meeting point of the superficial and deep layers of the pelvis, contributing to the balance of biomechanical forces. The perineal body integrates the excretory functions of the urogenital and anorectal organs, absorbing posterior visceral movements. The integrity of this system is essential for maintaining continence and is closely linked to the respiratory function of the diaphragm, as well as the postural and locomotor functions of the trunk and lower limbs. In the female body, hormones during pregnancy affect tissue density and regulate the elongation properties of the perineal body and the pelvic soft tissues, allowing for stretching during childbirth.[5]

Embryology

Two muscle groups emerge during the concurrent development of the 1st anlage of the pelvic organs. These muscle groups are the pubis-caudal group and the cloacal group, also known as the Gegenbauer muscle.

The pubis-caudal group gives rise to the coccygeal muscle and the levator ani muscle. These muscles, along with their fibrous differentiations, give rise to important ligaments in the pelvic region. These fibrous structures include the pubic-sacral or pubic-urethra-bladder-recto-sacral ligaments in the male body and the pubic-urethra-bladder-uterus-recto-sacral ligaments in the female body. The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments also originate from the pubis-caudal group.

The cloacal group contributes to the formation of several muscular structures after the genitourinary septum descends and separates the rectum in the posterior pelvis from the bladder and urethra (or the vagina in women) in the anterior pelvis. The cloacal group gives rise to the sphincteric muscles of the anus and urethra, as well as the bulbocavernosus, ischiocavernosus, and both the superficial and deep transverse perineal muscles.

Various anatomical components within this group have close relationships and sometimes fuse. These components include the levator ani muscle associated with the rectum and urethra, the puborectalis muscle, the sphincter of the urethra surrounding the prostate, the external anal sphincter, and the deep transverse perineal muscle. These anatomical relationships are functionally significant, contributing to humans' upright posture and bipedal gait.[6] During early fetal development, the mesenchymal tissue separating the anal and vaginal orifices, along with the surrounding muscular cells, can be clearly identified in specimens.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The perineal body receives its blood supply from the perineal branches of the pudendal vessels, which provide nourishment to the superficial and muscular tissues of the perineum, as well as the tissues located inferior to the levator ani muscle. The lymphatic vessels form a drainage network parallel to that of the blood vessels.[8]

Nerves

The perineal body is mainly innervated by the perineal nerve, the broader and inferior terminal branch of the pudendal nerve.[9] This nerve travels anteriorly, inferior to the internal pudendal artery. The perineal artery and nerve run together, with the nerve dividing into posterior scrotal (or labial) and muscular branches.

The posterior scrotal or labial branches split into medial and lateral branches. These nerves either penetrate the inferior sheet of the urogenital diaphragm or run along its lower surface, moving anteriorly through the lateral wall of the urogenital tract alongside the scrotal or labial branches of the perineal artery. These nerves supply the skin of the vulva or scrotum, and they anastomose with the perineal branch of the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh and the inferior rectal nerve.

The muscular branches innervate various muscles, including the superficial transverse perineal muscle, the bulbocavernosus, the ischiocavernosus, the deep transverse perineal muscle, the urethral sphincter, the anterior portion of the external anal sphincter, and the levator ani muscle. Additionally, a branch called the "nerve of the bulb of the urethra" arises from the nerve directed to the bulbocavernosus. This branch crosses the muscle and innervates the spongy body of the urethra, ending in the urethral mucosa.

Muscles

Several muscles form and are attached to the perineal body. The anatomic relationships and functions of these muscles are explained in this section.

Superficial Transverse Muscle of the Perineum

The superficial transverse muscle of the perineum is a thin muscular lamina that stretches transversely across the anterior region of the perineum, located deep to the superficial perineal fascia. This muscle forms the posterior boundary of a muscular triangle within the anterior perineum. The muscle originates from the inner surface of the ischial tuberosity and inserts into the central tendon of the perineum, where its fibers cross over to the contralateral side, creating a crisscross pattern. The fibers may also merge with the bulbocavernosus muscle and the external anal sphincter muscle (EAS).[10] In some cases, the muscle may integrate with both the bulbocavernosus and EAS. Alongside the deep transverse muscle, the superficial transverse muscle of the perineum plays a role in stabilizing the perineal body.

Bulbocavernosus

The bulbocavernosus muscle in male individuals consists of 2 symmetrical portions connected by a thin medial tendon. The muscular bundles originate from this raphe and the perineal body, continuing contralaterally to integrate with the transverse muscle and EAS. The posterior bundles form a thin sheet and insert into the body of the perineum. The middle bundles encircle the urethral bulb and the adjacent portion of the spongy body of the penis, attaching to the dorsal surface and intertwining with the lateral bundles. The anteriormost bundles spread out and embrace the cavernous bodies and dorsal vessels of the penis.

The bulbocavernosus aids in the emptying of the urethra after bladder evacuation, relaxing during urination and activating at the end of the process. The middle bundles contribute to the erection of the corpus cavernosum by compressing the erectile tissue of the bulb, while the anterior bundles help compress the deep dorsal vein of the penis.

In female individuals, the bulbocavernosus muscle covers the superficial parts of the bulbs of the vestibule and the major vestibular glands, extending anteriorly to surround the vaginal wall and attach to the bodies of the clitoris. The muscle bundles insert posteriorly into the perineal body, blending with those of the EAS and the contralateral transverse muscle. Contraction of the muscle narrows the vaginal orifice, stimulates the secretion of the Bartholin glands, and, by compressing the deep dorsal vein of the clitoris, contributes to erection.[11]

External Sphincter of the Anus

The EAS is a striated muscle tube located outside the external muscular tunic of the rectum. This muscle encircles the anal canal and extends approximately 4 cm in male individuals and 3 cm in female individuals, forming a sleeve about 3 mm thick composed of right and left halves that function as a unit. Classically, the EAS is described as having 3 parts.[12]

The deep portion is a thick annular band surrounding the most cranial segment of the internal anal sphincter. The muscle's deep fibers are fused and indistinguishable from those of the puborectalis. Anteriorly, many bundles intersect and continue with the superficial transverse muscle of the perineum, particularly in the female body. Posteriorly, some bundles may attach to the anococcygeal raphe.

The superficial portion lies above the subcutaneous part and surrounds the caudal portion of the internal sphincter. When viewed from the anus, this region appears elliptical and attaches anteriorly to the body of the perineum and posteriorly to the anterior surface of the last coccygeal segment via the anococcygeal raphe. This part of the EAS is the only component anchored entirely to bone.

The subcutaneous portion is a flat band, approximately 15 mm wide, that overlays the superficial layer at the level of the anal orifice, just deep to the skin. Anterior fibers insert into the body of the perineum or the superficial transverse muscle of the perineum. Posterior bundles usually attach to the anococcygeal ligament.

Some studies suggest that the EAS is organized into loops with significant interindividual variability rather than forming a continuous ring. The fibers that extend into the perineal body are associated with the bulbocavernosus.

Internal Sphincter of the Anus

The internal sphincter of the anus (IAS) is a smooth muscle composed of an annular thickening, measuring 5 to 8 mm in thickness, within the inner circular layer of the rectal muscular tunic. The IAS encircles the upper 3/4 (approximately 30 mm) of the anal canal, extending from the anorectal junction to the line separating the subcutaneous portion of the EAS from the lower margin of the internal sphincter. The IAS ends with a lower rounded margin that is distinct and readily appreciable by palpation.

The outer longitudinal layer of the rectum continues inferiorly and, passing through the pelvic diaphragm, merges with the levator ani muscle through elastic muscular expansions and connective fibers associated with the overlying endopelvic fascia. This structure, known as the conjoint longitudinal muscle coat, extends inferiorly, positioned between the internal and external anal sphincters.

The fibroelastic and muscular bundles penetrate the internal sphincter up to the muscularis mucosae of the anal canal, forming the muscle of the submucosa of the anus. Inferiorly, these structures pass through the subcutaneous portion of the EAS to join the perianal skin. The muscular components of the septa contribute to the corrugating muscle of the anal skin.

External Urethral Sphincter

The external urethral sphincter (EUS) is a layer of striated muscle surrounding the smooth muscle layer of the urethra. The EUS extends upward from the base of the bladder to the perineal membrane, corresponding to the area of maximum urethral closure. The levator ani muscle fibers encircle the EUS as the urethra passes through the pelvic floor, forming the periurethral sphincter. Some studies indicate a direct connection between the EUS and the periurethral bundles of the levator ani muscle, while others suggest that the 2 structures are separated by a continuous band of connective tissue.

In male individuals, the EUS is divided into 3 portions. The prostatic portion resembles an open-back shower, formed by transversely oriented fibers that encircle the anterior surface of the prostate and extend laterally. The trigonal portion is a muscular ring that completely surrounds the membranous urethra as it passes through the perineal membrane. The bulbourethral portion is a muscular lamina originating from the urogenital triangle, surrounding the urethra and terminating posteriorly in the perineal body, where it encases the bulbourethral glands.

In female individuals, the EUS is made up of striated circular fibers and also consists of 3 distinct parts. The proximal portion forms a complete muscular ring surrounding the smooth muscle of the urethra. The middle portion is the most developed and is responsible for maximum urethral closing pressure. The distal portion, known as the urogenital sphincter, is positioned near the urogenital diaphragm and superior to the perineal membrane. Some fibers encircle both the urethra and the vagina, forming the urethrovaginal sphincter, while other fibers extend laterally and attach to the pubic rami, creating an open posterior ring called the "compressor urethrae."[13] These fibers are referred to in male individuals as the "deep transverse perineal muscle."

Deep Transverse Muscle of the Perineum

The deep transverse muscle of the perineum is a laminar muscle arranged transversely superior to the superficial layer of the perineal membrane in the male body. The muscle bundles insert laterally on the inner surface of the ischium and cross medially with the contralateral muscle, contributing to the formation of the perineal body. The fibers join the deep part of the EAS posteriorly and the urethral sphincter anteriorly.

In the female body, the deep transverse muscle of the perineum is replaced by 2 muscles. The compressor urethrae consists of bundles originating from the ischiopubic ramus that run anteriorly and cross over to form a flat, layered structure located anterior to the urethra and inferior to the urethral sphincter. Other fibers with a similar origin extend medially toward the vagina and, in rare cases, reach the perineal body, forming a true deep transverse perineal muscle. The urethrovaginal sphincter muscle originates from the perineal body and extends anteriorly along the sides of the vagina and urethra, crossing contralaterally to create a thin, flat muscle layer anterior to the urethra and inferior to the compressor urethrae. This muscle plays an essential role in maintaining urinary continence.[14]

Puborectalis

The puborectalis muscle forms the major portion of the levator ani muscle. At its pubic origin, the puborectalis is inseparable from the pubococcygeal muscle. This muscle's bundles converge with those of the contralateral side to create a sling around the anorectal junction. At the perineal body, the puborectalis connects to the EAS through fibrous tissue.

Longitudinal Anal Muscle

The LAM is a vertical layer of muscle tissue situated between the IAS and the EAS and is part of the descending longitudinal rectal muscle originating from the levator ani muscle. LAM fibers are spiral in orientation, shortening the anal canal during contraction and contributing to continence. At the most caudal part, smooth muscle bundles called the "corrugator cutis ani" extend through the distal anal sphincter into the perianal skin and the ischiorectal fossa.[15]

Rectourethral Muscle

The rectourethral muscle is located at the superior part of the EAS, connecting the longitudinal muscle of the rectum from below to the Denonvilliers fascia from above. This muscle is the passageway for a vein and the cavernous nerve.

Perineal Lateral Smooth Muscles

The perineal lateral smooth muscles are situated on the lateral side of the perineal body and are covered by skin. These muscles receive fibers from the LAM, which continue anteriorly toward the vestibular region of the superficial perineal fascia.[16]

Surgical Considerations

The perineal body is essential in maintaining continence, serving as the central structure in Level III of the DeLancey continence system.[17] Damage to the perineal body often occurs during childbirth, either from spontaneous tears or episiotomy, and overstretching can lead to neural and musculofascial injuries. A perineal body injury may result in a rectocele, characterized by the perineal body's separation into 2 segments connected by a stretched and weakened central portion.[18]

Clinical Significance

The perineal body is a structure that must be assessed when evaluating pelvic floor function. The perineal body moves inferiorly during inhalation as the pelvic floor muscles relax and superiorly during exhalation as these muscles contract. During a voluntary squeeze, the perineal body lifts anterosuperiorly. Manual vaginal palpation is used to evaluate pelvic floor muscle strength.[19] Movement of the perineal body against the examiner's fingers, inserted into the vagina, is restricted during active muscle contraction. Muscle strength is graded using the Modified Oxford Grading System, with severity scores as follows:

- 0 = No contraction

- 1 = Flicker

- 2 = Weak

- 3 = Moderate

- 4 = Good (with lift)

- 5 = Strong

An alternative method involves external palpation of the perineal body using a light touch to detect the balance of forces from tissues converging on the perineal body. This assessment relies on proprioceptive and tactile perception. Conceptually, the perineal body may be visualized as a knot formed by multiple interconnected strings. The position and movement of the "knot" reflect the tension of the surrounding "strings," with imbalances resulting in impaired movement or positional changes.[20]

Other Issues

Perineal massage appears to be a manual practice that may help women during childbirth. However, no standardized approach has been established.[21]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kraima AC, West NP, Treanor D, Magee D, Roberts N, van de Velde CJ, DeRuiter MC, Quirke P, Rutten HJ. The anatomy of the perineal body in relation to abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2016 Jul:18(7):688-95. doi: 10.1111/codi.13138. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26407538]

Hinata N, Hieda K, Sasaki H, Kurokawa T, Miyake H, Fujisawa M, Murakami G, Fujimiya M. Nerves and fasciae in and around the paracolpium or paravaginal tissue: an immunohistochemical study using elderly donated cadavers. Anatomy & cell biology. 2014 Mar:47(1):44-54. doi: 10.5115/acb.2014.47.1.44. Epub 2014 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 24693482]

Wu Y, Dabhoiwala NF, Hagoort J, Hikspoors JPJM, Tan LW, Mommen G, Hu X, Zhang SX, Lamers WH. Architecture of structures in the urogenital triangle of young adult males; comparison with females. Journal of anatomy. 2018 Oct:233(4):447-459. doi: 10.1111/joa.12864. Epub 2018 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 30051458]

Larson KA, Yousuf A, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Fenner DE, DeLancey JO. Perineal body anatomy in living women: 3-dimensional analysis using thin-slice magnetic resonance imaging. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010 Nov:203(5):494.e15-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21055513]

Jing D, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. A subject-specific anisotropic visco-hyperelastic finite element model of female pelvic floor stress and strain during the second stage of labor. Journal of biomechanics. 2012 Feb 2:45(3):455-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.12.002. Epub 2011 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 22209507]

Hall MI, Rodriguez-Sosa JR, Plochocki JH. Reorganization of mammalian body wall patterning with cloacal septation. Scientific reports. 2017 Aug 23:7(1):9182. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09359-y. Epub 2017 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 28835612]

Nyangoh Timoh K, Moszkowicz D, Zaitouna M, Lebacle C, Martinovic J, Diallo D, Creze M, Lavoue V, Darai E, Benoit G, Bessede T. Detailed muscular structure and neural control anatomy of the levator ani muscle: a study based on female human fetuses. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jan:218(1):121.e1-121.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.09.021. Epub 2017 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 28988909]

Kimmig R, Thangarajah F, Buderath P. Sentinel Lymph node detection in endometrial cancer - Anatomical and scientific facts. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2024 Jun:94():102483. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2024.102483. Epub 2024 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 38401483]

Osmonov D, Wilson SK, Heinze T, Heimke M, Novak J, Ragheb A, Köhler T, Hatzichristodoulou G, Wedel T. Anatomic considerations of inflatable penile prosthetics: lessons gleaned from surgical body donor workshops. International journal of impotence research. 2023 Nov:35(7):672-678. doi: 10.1038/s41443-023-00715-3. Epub 2023 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 37179421]

Shafik A, Sibai OE, Shafik AA, Shafik IA. A novel concept for the surgical anatomy of the perineal body. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2007 Dec:50(12):2120-5 [PubMed PMID: 17909903]

Wobser AM, Adkins Z, Wobser RW. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Bones (Ilium, Ischium, and Pubis). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137809]

Nauman K, Samra NS. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Anal Triangle. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491517]

Sam P, Jiang J, Leslie SW, LaGrange CA. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sphincter Urethrae. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494045]

Bolla SR, Hoare BS, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Deep Perineal Space. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855860]

Wu Y, Dabhoiwala NF, Hagoort J, Shan JL, Tan LW, Fang BJ, Zhang SX, Lamers WH. 3D Topography of the Young Adult Anal Sphincter Complex Reconstructed from Undeformed Serial Anatomical Sections. PloS one. 2015:10(8):e0132226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132226. Epub 2015 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 26305117]

Lee JM, Kim NK. Essential Anatomy of the Anorectum for Colorectal Surgeons Focused on the Gross Anatomy and Histologic Findings. Annals of coloproctology. 2018 Apr:34(2):59-71. doi: 10.3393/ac.2017.12.15. Epub 2018 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 29742860]

Ashton-Miller JA, Howard D, DeLancey JO. The functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor and stress continence control system. Scandinavian journal of urology and nephrology. Supplementum. 2001:(207):1-7; discussion 106-25 [PubMed PMID: 11409608]

Wagenlehner FM, Del Amo E, Santoro GA, Petros P. Live anatomy of the perineal body in patients with third-degree rectocele. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2013 Nov:15(11):1416-22. doi: 10.1111/codi.12333. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23819818]

Chevalier F, Fernandez-Lao C, Cuesta-Vargas AI. Normal reference values of strength in pelvic floor muscle of women: a descriptive and inferential study. BMC women's health. 2014 Nov 25:14():143. doi: 10.1186/s12905-014-0143-4. Epub 2014 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 25420756]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceB SN, Rodenbaugh DW. Modeling the anatomy and function of the pelvic diaphragm and perineal body using a "string model". Advances in physiology education. 2008 Jun:32(2):169-70. doi: 10.1152/advan.00106.2007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18539862]

Li Y, Wang C, Lu H, Cao L, Zhu X, Wang A, Sun R. Effects of perineal massage during childbirth on maternal and neonatal outcomes in primiparous women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of nursing studies. 2023 Feb:138():104390. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104390. Epub 2022 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 36442355]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence