Introduction

The orbital apex disorders include superior orbital fissure syndrome, cavernous sinus syndrome, and orbital apex syndrome.[1] Though these disorders have been described separately based on the anatomical site of involvement and clinical features, the evaluation and management of these conditions are almost alike.[2]

Orbital apex syndrome (OAS), also called Jacod syndrome, is a complex neurological disorder characterized by a constellation of signs resulting from multiple cranial nerve involvement.[3] The typical clinical features are attributed to the involvement of the orbital apex by various neoplastic, vascular, infectious, or inflammatory conditions. They primarily involve one of the adjacent structures like the paranasal sinuses or the orbit from which they spread to the orbital apex.[4] Hence, understanding the etiology of the orbital apex syndrome with early recognition and swift treatment may help reduce associated comorbidities.

Anatomy of the Orbital Apex

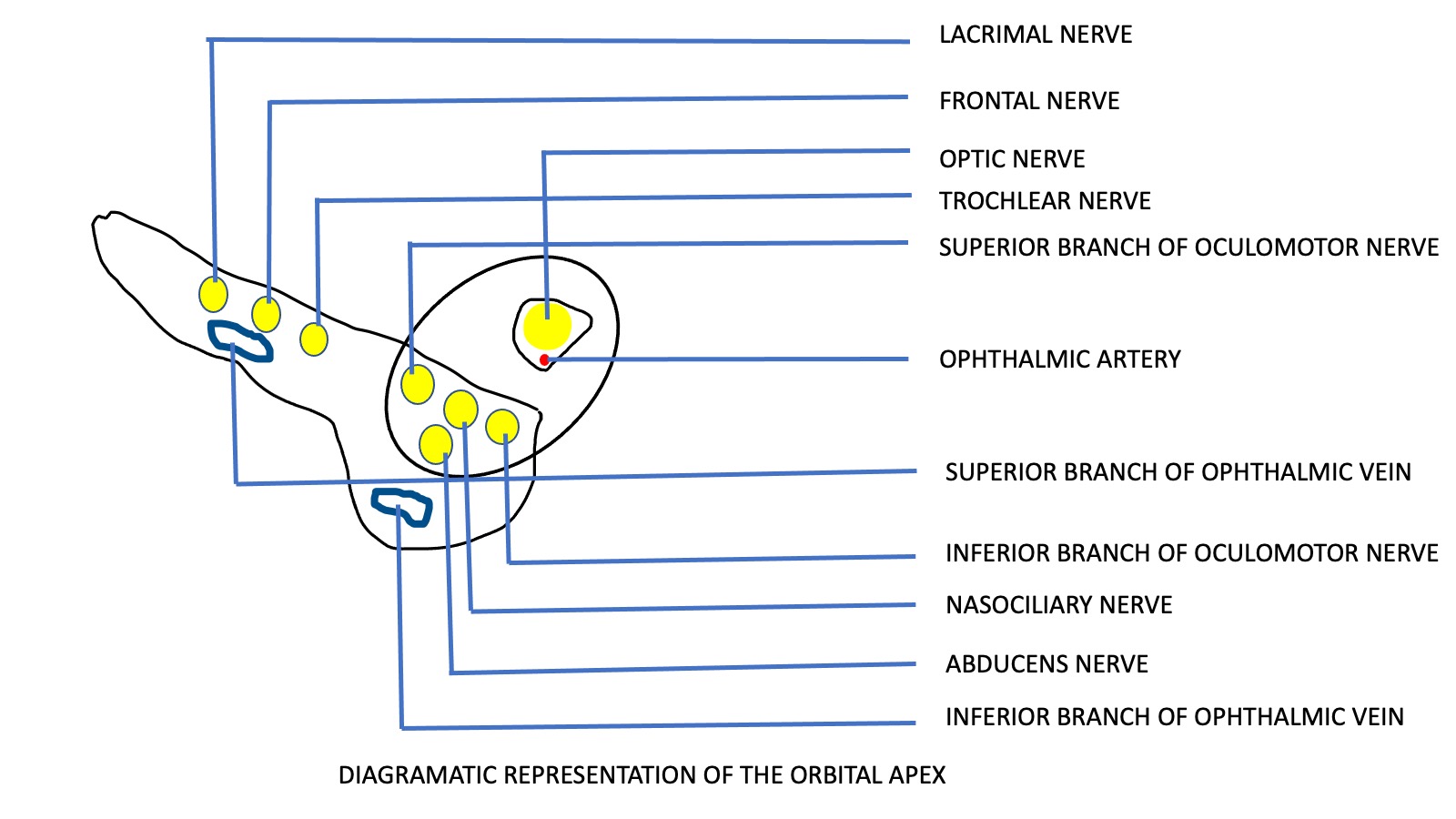

The orbital apex is an opening connecting the orbit and the cranial cavity.[5] The roof of the orbital apex is contributed by the lesser wing of the sphenoid, the lateral wall by the greater wing of the sphenoid, the medial wall by the ethmoidal sinus, and the floor by the orbital plate of the palatine bone.[6] The bony orbital apex consists of the optic canal superomedially and the orbital apex inferolateral. The contents of the optic canal include the optic nerve, ophthalmic artery, and the postganglionic sympathetic fibers from the carotid plexus.[7]

The intracanalicular part of the optic nerve is present above the orbital apex, passes through the optic canal, and runs to the posteromedial optic chiasm. The middle portion of the superior orbital fissure contains the cranial nerves III, IV, and VI and the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (V1). The annulus of Zinn is a fibrous chord located superior and medial to the superior orbital fissure.[8] The annulus of Zinn is the common origin of the four rectus muscles and contains the optic nerve and ophthalmic artery in the optic foramen.

Knowledge of the anatomy of the orbital apex and its contents is essential to diagnosing and managing orbital syndromes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Table 1. Orbital apex syndrome (OAS) has multiple etiologies, and the management is directed toward the specific cause in each patient.

| Cause | Description |

| Infectious |

OAS can be caused by bacterial, fungal, viral, and parasitic infections. These organisms primarily involve the surrounding structures like the orbit or the paranasal sinuses, from where they spread contiguously to the orbital apex resulting in the typical clinical features. Bacteria Gram-positive cocci like Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pneumoniae and gram-negative bacilli like Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Proteus, and anaerobic bacteria may cause sinusitis or orbital cellulitis that spreads to involve the orbital apex.[9][10] The susceptible group of patients includes immunocompromised patients and those with uncontrolled hyperglycemia. The mechanism is thought to be due to the production of toxins and lipopolysaccharide that aids in the dissemination of infections. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and spirochaetes have also been implicated in causing OAS.[11][12] Fungi The most common fungi involved in OAS include Mucor and Aspergillus. They commonly occur in patients with uncontrolled sugars, immunosuppression, and patients undergoing treatment for various malignancies. They primarily affect the paranasal sinuses or the vertebrae and spread to the orbital apex by hematogenous spread. If left untreated, they may involve the central nervous system and may be fatal.[13][14][15][16] Virus OAS can occur following herpes zoster ophthalmicus in immunocompromised individuals. The mechanism may be due to the direct cytopathic effect of viruses, immune-mediated damage, or due to inflammatory edema.[17][18] Parasite Cysticercosis occurs due to infection with Taenia solium or Taenia saginatum. Though the central nervous system and the eye are the most commonly involved organs, the cysts may also affect the optic nerve or the orbital apex.[19][20]

|

| Inflammatory |

OAS may occur secondary to systemic autoimmune disorders like granulomatosis with polyangiitis, sarcoidosis, microscopic polyangiitis, Churg Strauss syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and giant cell arthritis. OAS may occur secondary to idiopathic orbital inflammation. Tolosa hunt syndrome is an idiopathic granulomatous inflammation affecting the orbital apex or cavernous sinus. Other systemic manifestations involving the kidneys, lungs, skin, and central nervous system may be present. Infectious causes must be ruled out before commencing treatment for inflammation.[21][22] |

| Neoplastic |

Benign Neurofibromas, dermoid cysts, epidermoid cysts, and fibrous dysplasia may cause OAS by compression of structures at the orbital apex.[23] Malignant OAS may be caused by primary head and neck malignancies or by secondary metastasis. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma have been documented to be associated with OAS. The common sites of origin of metastasis to the orbital apex include breast, lung, and renal carcinoma and malignant melanoma. Leukemias and nonhodgkins lymphoma may also cause OAS.[24][25][26][27] |

| Traumatic | Blunt and penetrating maxillofacial and cranial injuries may lead to orbital apex syndrome due to direct impingement by a bony fragment, inflammatory soft tissue edema, hematoma, or foreign bodies.[28] Iatrogenic causes include otorhinolaryngological procedures like sinus surgeries, surgeries for nasal polyps, and ethmoidal artery ligations for epistaxis.[29][30][31] |

| Vascular | Vascular causes include carotid-cavernous fistulas, carotid-cavernous aneurysms, and cavernous sinus thrombosis.[32] |

| Endocrine | Thyroid eye disease may cause a crowded orbital apex resulting in the compression of the structures and result if features of orbital apex syndrome.[33] |

Epidemiology

Orbital apex syndrome is a rare condition, and limited data are available on the incidence of orbital apex syndrome in the United States of America and worldwide. No specific racial or male-female predisposition for this condition is evident. OAS is found worldwide and may occur secondary to one of the etiological conditions described below.[3]

History and Physical

Characteristic signs of orbital apex syndrome (OAS) are painful external ophthalmoplegia with vision loss. The ophthalmologist may be the primary physician to suspect and diagnose orbital apex syndrome. Patient symptoms include reduced or total loss of vision on the involved side, torsional, horizontal, or vertical diplopia, inability to open the eye, prominence of the eyeball, difficulty moving the eye in different gazes, facial pain, and abnormal head postures.

The prior medical history may be significant for one or many conditions predisposing to OAS. Patients may have a history of uncontrolled high blood sugars at presentation or in the recent past; a history of immunosuppression or malignancy may predispose an individual to infectious involvement of the orbital apex.[34] They may have symptoms or a history of being treated for fungal or bacterial sinusitis in the recent past.[35][36] History of vesicular rash in dermatomal distribution of the trigeminal nerve may indicate a viral etiology.[37] A history of a preexisting malignancy may suggest a neoplastic cause of OAS. Inflammatory orbital apex syndrome may be sudden in onset and is associated with pain at presentation. Tolosa hunt syndrome is associated with a typical boring or gnawing pain.[38]

The clinical signs of orbital apex syndrome are due to the involvement of the optic nerve, oculomotor nerve, trochlear nerve, abducens nerve, and the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve. The signs which may be present on examining a patient with orbital apex syndrome include proptosis, defective vision, a relative afferent pupillary defect due to involvement of the optic nerve, restricted ocular movement due to the involvement of the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerve, facial pain and paresthesia over the forehead and the upper lid due to the involvement of the ophthalmic division of trigeminal nerve, and anisocoria due to the involvement of the pupillary fibers. In addition, optic disc edema, pallor, or choroidal folds may also be seen. Pulsatile proptosis with a preceding history of a head injury may indicate a vascular etiology like a carotid-cavernous fistula.[39]

Evaluation

Evaluation is directed toward identifying the specific cause to institute appropriate therapy.

Laboratory Evaluation

Various tests are required in appropriate clinical settings.[40] These include:

- Complete blood count, peripheral smear

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein

- Gram stain and culture on blood agar

- Potassium hydroxide mount, Sabourauds dextrose agar

- Polymerase chain reaction

- Veneral Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA), rapid plasma reagin (RPR)

- Mantoux test, high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) chest, interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) for tuberculosis

- Blood sugars, glycosylated hemoglobin

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- Perineuclera and cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (P ANCA & C ANCA) and anti-nuclear antibody (ANA)

- Orbital doppler, orbital ultrasounds, CT angiography, and catheter angiography

Radiological Investigations

The 3-tesla MRI is superior to 1 to 1.5-tesla MRI to visualize the sellar anatomy and deduce the involvement of the cavernous sinus. MRI imaging with contrast and fat suppression may help us to visualize the orbital apex. Computed tomography (CT) is superior to magnetic resonance imaging in visualizing the bony anatomy.

Table 2. Radiological Investigations

| Cause | Computed Tomography | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| Infectious[41] |

CT may help in imaging the paranasal sinuses to look for features of sinusitis, pre-existing orbital cellulitis, or subperiosteal abscess. |

Hypointense in T1 weighted images and hyperintense in T2 weighted images. It has a cone shape when the infection is localized to the orbital apex and a dumbbell shape when the superior orbital fissure is involved. |

| Inflammatory[40][42][43] |

MRI is preferred over CT. |

|

| Traumatic[44][45][46] | CT is indicated to visualize and evaluate cranial maxillofacial fractures as it is superior to MRI in deducing bony deformities. It is also the investigation of choice when a magnetic foreign body is suspected, as MRI is contraindicated. | MRI helps in detecting soft tissue swelling and nerve injuries. |

| Neoplastic[24][47][48] | CT may be required to detect bony metastasis. | MRI helps detect local invasion, intracranial extension, detecting enhancement, thickening or compression of nerves, and tumor dimensions. |

| Vascular[49][50][51] | CT may help rule out bony fractures associated with traumatic causes of carotid-cavernous fistula. | Contrast may be required to differentiate between thrombosed (rim enhancement due to central filling defect)and non-thrombosed aneurysms (uniform filling). Digital subtraction angiography may be indicated for the detection of smaller lesions. |

Treatment / Management

Table 3.

(A1)| Cause | Description |

| Infectious |

In the presence of significant optic nerve involvement, high-dose steroid therapy can be initiated with appropriate antimicrobial cover. Bacteria The organisms are isolated from swabs, tissue culture, blood or urine culture, and sensitivity to various antibiotics is deduced to initiate the appropriate systemic antibiotics.[52][53][54] Fungi Mucor is usually treated by intravenous infusion of liposomal amphotericin B, a broad-spectrum anti-fungal agent, and aspergillus is usually treated with intravenous voriconazole.[55][36][13] Virus Combined antiviral and steroid therapy is required for patients with OAS following herpes zoster ophthalmics. Intravenous acyclovir is the drug of choice for orbital apex syndrome following herpes zoster ophthalmicus.[56][57] Oral valacyclovir or acyclovir can be used in the maintenance phase of treatment. Parasite Cysticercosis is treated with anti-helminthic agents along with steroids to avoid adverse reactions due to intense inflammation caused by the death of the cestode. Surgical treatment is required in patients unresponsive to anti-helminthic therapy or with compressive symptoms.[20][19] |

| Inflammatory |

OAS secondary to various systemic autoimmune disorders is usually managed by systemic steroid therapy. Patients with recurrences while tapering steroids and steroid dependant patients may need immunosuppressive. Methotrexate and azathioprine have been used successfully in the management of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome.[58][59][60] |

| Traumatic | Immediate decompression by dislodgement of bony fragments, removal of foreign bodies, and fixation of fractures may be required in appropriate clinical settings. High-dose systemic steroids may also be required to reduce inflammatory soft tissue edema and hematoma.[61][62] |

| Vascular | They may be managed conservatively but may require balloon ligation and direct or indirect surgical procedures in selected cases.[39] |

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of OAS is the other two orbital syndromes - the superior orbital fissure syndrome and the cavernous sinus syndrome.

The superior orbital fissure syndrome (SOF), also known as the Rochen- Duvigneaud syndrome, is characterized by the involvement of the III, IV, VI, and the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. Still, it differs from OAS with the sparing of the optic nerve.[63] The cavernous sinus syndrome, besides the features of the OAS, is characterized by the involvement of the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve and the oculosympathetic fibers.[64]

The causative pathologies of these orbital apex syndromes are identical and are named individually to highlight the anatomical site of involvement and may represent a continuum of the same spectrum. One of the predominant features of OAS is total ophthalmoplegia; hence other muscular and neuromuscular causes of total ophthalmoplegia, like myasthenia gravis, congenital muscle fibrosis, and supranuclear palsy, should be ruled out.[65]

Prognosis

OAS responds to treatment within 48 to 72 hours once therapy is initiated. An accurate diagnosis of the etiology and instituting prompt specific treatment determines the prognosis of patients with OAS. A subset of patients with Tolosoa-Hunt syndrome may relapse, present with residual neurological deficits, and may need immunosuppressants. The presence of orbital apex syndrome in a patient with primary or secondary neoplasms and hematological malignancies may indicate a poor chance of survival.[66]

Complications

The involvement of the optic nerve may result in optic atrophy in certain patients, resulting in subnormal visual acuity, color vision, and permanent field defects. Sub-optimal management of infections and inflammations may prolong the clinical course and result in frequent relapses and permanent visual disability. Irreversible vision loss may occur on the involved side in case of optic nerve damage. If it extends to involve the cavernous sinus and is left untreated, it may be potentially fatal for the patient.[3]

Consultations

The crux of orbital apex syndrome lies in identifying the etiological cause, prompt diagnosis, and a multidisciplinary approach. Though the initial presentation may be to the ophthalmologist, referral to a neuro physician, neurosurgeon, diabetologist, otorhinolaryngologist, and ophthalmologist may be required in appropriate clinical settings.[40]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with uncontrolled diabetes, immunosuppression, and undergoing immunosuppressive treatments for autoimmune and other conditions must be educated about the risks of infections and how a delay in seeking medical attention can cause a risk of spread of infections to involve vital orbital and intracranial structures. Patients must be educated about the symptoms of orbital apex syndrome and instructed to seek medical evaluation at the earliest.

Pearls and Other Issues

Any patient presenting with a single cranial nerve palsy should be thoroughly investigated for focal neurological deficits and the involvement of other cranial nerves.[3] A complete central nervous system examination and systemic examination are essential to arrive at an accurate diagnosis. Baseline blood and systemic workups are essential and are individualized according to the patient’s age, history, and clinical signs.[34]

Neuroimaging, including computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, is done to diagnose associated bony abnormalities and soft tissue pathologies, respectively.[41] Knowledge of the etiopathogenesis of orbital apex syndrome is essential in diagnosing and managing the disease.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Management of orbital apex syndrome (OAS) requires a multidisciplinary approach to identify the cause and institute specific therapy. The ophthalmologist may be the first to diagnose orbital apex syndrome since most of the symptoms are visual, like a decrease in best-corrected visual acuity, diplopia, and reduced eye movement.

The otorhinolaryngologist plays a vital role by performing endoscopic resection of tissues through functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS), the histopathological examination of which may be vital in identifying the cause. Clinicians and rheumatologists are indispensable in managing OAS secondary to systemic autoimmune diseases. The oncologist plays a crucial role in identifying and managing orbital apex syndrome secondary to primary malignancies and metastasis, thereby improving the patient's chances of survival.

The vascular surgeon is essential in managing carotic cavernous fistula, sinus, and cavernous sinus thrombosis. The general physician, diabetologist, and infectious disease specialist are vital in managing infectious causes of orbital apex syndrome. The outcomes and prognosis of OAS depend on the cause and the patient's general systemic condition; hence a multispeciality approach may help adequately treat the patient.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Azzam D, Cypen S, Tao J. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Eye Ophthalmic Vein. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491535]

Bhatti MT. Orbital syndromes. Seminars in neurology. 2007 Jul:27(3):269-87 [PubMed PMID: 17577868]

Badakere A, Patil-Chhablani P. Orbital Apex Syndrome: A Review. Eye and brain. 2019:11():63-72. doi: 10.2147/EB.S180190. Epub 2019 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 31849556]

Li Y, Wu W, Xiao Z, Peng A. Study on the treatment of traumatic orbital apex syndrome by nasal endoscopic surgery. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2011 Mar:268(3):341-9. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1409-6. Epub 2010 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 20978778]

Engin Ӧ, Adriaensen GFJPM, Hoefnagels FWA, Saeed P. A systematic review of the surgical anatomy of the orbital apex. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2021 Feb:43(2):169-178. doi: 10.1007/s00276-020-02573-w. Epub 2020 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 33128648]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHu S, Colley P. Surgical Orbital Anatomy. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2019 May:33(2):85-91. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1685476. Epub 2019 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 31037044]

Pooshpas P, Nookala V. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Optic Canal. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424751]

Caldarelli C, Benech R, Iaquinta C. Superior Orbital Fissure Syndrome in Lateral Orbital Wall Fracture: Management and Classification Update. Craniomaxillofacial trauma & reconstruction. 2016 Nov:9(4):277-283 [PubMed PMID: 27833704]

Kusunoki T, Kase K, Ikeda K. A case of orbital apex syndrome due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Clinics and practice. 2011 Sep 28:1(4):e127. doi: 10.4081/cp.2011.e127. Epub 2011 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 24765368]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeung V, Dunn H, Newey A, O'Donnell B. Orbital Apex Syndrome in Pseudomonas Sinusitis After Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2018 Sep/Oct:34(5):e166-e168. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001196. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30124608]

Hughes EH, Petrushkin H, Sibtain NA, Stanford MR, Plant GT, Graham EM. Tuberculous orbital apex syndromes. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Nov:92(11):1511-7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.138974. Epub 2008 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 18614572]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceValentin L, Virieu R, Dumas M, Collomb H. [Syndrome of the orbital apex and syphilitic meningoencephalitis]. Revue d'oto-neuro-ophtalmologie. 1970 Dec:42(8):482-6 [PubMed PMID: 5510651]

Marzoughi S, Chen T. Orbital Apex Syndrome Due to Mucormycosis - Missed on Initial MRI. The Neurohospitalist. 2022 Jan:12(1):127-130. doi: 10.1177/19418744211025369. Epub 2021 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 34950400]

Godinho G, Abreu I, Alves G, Vaz R, Leal V, Carvalho AC, Sarmento A, Falcão-Reis F. Orbital Apex Syndrome due to Orbital Mucormycosis after Teeth Infection: A Successful Case Report. Case reports in ophthalmology. 2021 Jan-Apr:12(1):110-115. doi: 10.1159/000510389. Epub 2021 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 33976666]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePellegrini F, Mandarà E, Stafa A, Meli S. Frozen overnight: Acute orbital apex syndrome caused by aspergillosis. European journal of ophthalmology. 2023 May:33(3):NP45-NP48. doi: 10.1177/11206721211073447. Epub 2022 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 35001696]

Cullen GD, Davidson TM, Yetmar ZA, Pritt BS, DeSimone DC. Orbital apex syndrome due to invasive aspergillosis in an immunocompetent patient. IDCases. 2021:25():e01232. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01232. Epub 2021 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 34377667]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRuiz-Arranz C, Reche-Sainz JA, de Uña-Iglesias MC, Ortueta-Olartecoechea A, Muñoz-Gallego A, Ferro-Osuna M. Orbital apex syndrome secondary to herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Archivos de la Sociedad Espanola de Oftalmologia. 2021 Jul:96(7):384-387. doi: 10.1016/j.oftale.2020.06.009. Epub 2020 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 34217477]

Lim JJ, Ong YM, Wan Zalina MZ, Choo MM. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus with Orbital Apex Syndrome-Difference in Outcomes and Literature Review. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2018:26(2):187-193. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2017.1327604. Epub 2017 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 28622058]

Koirala B, Shah S, Sitaula S, Shrestha GB. Orbital apex syndrome secondary to myocysticercosis: A case report from Nepal. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2022 Aug:80():104336. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104336. Epub 2022 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 36045756]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChaugule P, Varma DR, Patil Chhablani P. Orbital apex syndrome secondary to optic nerve cysticercosis. International ophthalmology. 2019 May:39(5):1151-1154. doi: 10.1007/s10792-018-0910-6. Epub 2018 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 29582260]

Kline LB, Hoyt WF. The Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2001 Nov:71(5):577-82 [PubMed PMID: 11606665]

Schmidt J, Pulido JS, Matteson EL. Ocular manifestations of systemic disease: antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2011 Nov:22(6):489-95. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834bdfe2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21918443]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBorchard NA, Nayak JV. Orbital Apex Syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Apr 26:378(17):e23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1703770. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29694826]

Shindler KS, Liu GT, Womer RB. Long-term follow-up and prognosis of orbital apex syndrome resulting from nasopharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma. American journal of ophthalmology. 2005 Aug:140(2):236-41 [PubMed PMID: 16023064]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGarala K, Jayaramachandran P, Knopp M, Critchley P. Orbital apex tumour caused by chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: an unlikely suspect. BMJ case reports. 2013 Jul 9:2013():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200166. Epub 2013 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 23843418]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePrado-Ribeiro AC, Luiz AC, Montezuma MA, Mak MP, Santos-Silva AR, Brandão TB. Orbital apex syndrome affecting head and neck cancer patients: A case series. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 2017 May 1:22(3):e354-e358 [PubMed PMID: 28390122]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYuen CA, Pula JH, Mehta M. Primary Ocular Adnexal Extranodal Marginal Zone Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) Lymphoma Presenting as Orbital Apex Syndrome. Neuro-ophthalmology (Aeolus Press). 2017 Apr:41(2):94-98. doi: 10.1080/01658107.2016.1263343. Epub 2017 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 28348632]

Imaizumi A, Ishida K, Ishikawa Y, Nakayoshi I. Successful Treatment of the Traumatic Orbital Apex Syndrome due to Direct Bone Compression. Craniomaxillofacial trauma & reconstruction. 2014 Dec:7(4):318-22. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390245. Epub 2014 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 25383156]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYeh S, Yen MT, Foroozan R. Orbital apex syndrome after ethmoidal artery ligation for recurrent epistaxis. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2004 Sep:20(5):392-4 [PubMed PMID: 15377911]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVassallo P, Tranfa F, Forte R, D'Aponte A, Strianese D, Bonavolontà G. Ophthalmic complications after surgery for nasal and sinus polyposis. European journal of ophthalmology. 2001 Jul-Sep:11(3):218-22 [PubMed PMID: 11681498]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJaison SG, Bhatty SM, Chopra SK, Satija V. Orbital apex syndrome: a rare complication of septorhinoplasty. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 1994 Dec:42(4):213-4 [PubMed PMID: 10577002]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Keizer R. Carotid-cavernous and orbital arteriovenous fistulas: ocular features, diagnostic and hemodynamic considerations in relation to visual impairment and morbidity. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2003 Jun:22(2):121-42 [PubMed PMID: 12789591]

Schaefer SD, Soliemanzadeh P, Della Rocca DA, Yoo GP, Maher EA, Milite JP, Della Rocca RC. Endoscopic and transconjunctival orbital decompression for thyroid-related orbital apex compression. The Laryngoscope. 2003 Mar:113(3):508-13 [PubMed PMID: 12616205]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSaini L, Chakrabarty B, Kumar A, Gulati S. Orbital Apex Syndrome: A Clinico-anatomical Diagnosis. Journal of pediatric neurosciences. 2020 Jul-Sep:15(3):336-337. doi: 10.4103/jpn.JPN_114_20. Epub 2020 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 33531965]

Lee PH, Shao SC, Lee WA. Orbital Apex Syndrome: A Case Series in a Tertiary Medical Center in Southern Taiwan. Frontiers in medicine. 2022:9():845411. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.845411. Epub 2022 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 35345765]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKim DH, Jeong JU, Kim S, Kim ST, Han GC. Bilateral Orbital Apex Syndrome Related to Sphenoid Fungal Sinusitis. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2023 Dec:102(12):NP618-NP620. doi: 10.1177/01455613211024768. Epub 2021 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 34281412]

Chiew YR, Ng GJ, Kong Y, Tan YJ. Orbital apex syndrome secondary to herpes zoster ophthalmicus: Clinical features and outcomes case report and systematic review. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2022 May:99():367-372. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2022.03.036. Epub 2022 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 35364439]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee KP, Sung PS, Lee WA. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome as initial presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Acta neurologica Taiwanica. 2021 Mar:30(1)():39-42 [PubMed PMID: 34549400]

Aryasit O, Preechawai P, Aui-Aree N. Clinical presentation, aetiology and prognosis of orbital apex syndrome. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2013 Apr:32(2):91-4. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2013.764439. Epub 2013 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 23514029]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYeh S, Foroozan R. Orbital apex syndrome. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2004 Dec:15(6):490-8 [PubMed PMID: 15523194]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoyal P, Lee S, Gupta N, Kumar Y, Mangla M, Hooda K, Li S, Mangla R. Orbital apex disorders: Imaging findings and management. The neuroradiology journal. 2018 Apr:31(2):104-125. doi: 10.1177/1971400917740361. Epub 2018 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 29415610]

Bone I, Hadley DM. Syndromes of the orbital fissure, cavernous sinus, cerebello- pontine angle, and skull base. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2005 Sep:76 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):iii29-iii38 [PubMed PMID: 16107388]

Gordon LK. Orbital inflammatory disease: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Eye (London, England). 2006 Oct:20(10):1196-206 [PubMed PMID: 17019419]

Steinsapir KD, Goldberg RA. Traumatic optic neuropathy: an evolving understanding. American journal of ophthalmology. 2011 Jun:151(6):928-933.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.02.007. Epub 2011 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 21529765]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWarner N, Eggenberger E. Traumatic optic neuropathy: a review of the current literature. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2010 Nov:21(6):459-62. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833f00c9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20829687]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUzelac A, Gean AD. Orbital and facial fractures. Neuroimaging clinics of North America. 2014 Aug:24(3):407-24, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2014.03.008. Epub 2014 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 25086804]

Valvassori GE, Sabnis SS, Mafee RF, Brown MS, Putterman A. Imaging of orbital lymphoproliferative disorders. Radiologic clinics of North America. 1999 Jan:37(1):135-50, x-xi [PubMed PMID: 10026734]

Robinson D, Wilcsek G, Sacks R. Orbit and orbital apex. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2011 Aug:44(4):903-22, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2011.06.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21819879]

Stiebel-Kalish H, Kalish Y, Bar-On RH, Setton A, Niimi Y, Berenstein A, Kupersmith MJ. Presentation, natural history, and management of carotid cavernous aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2005 Nov:57(5):850-7; discussion 850-7 [PubMed PMID: 16284555]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLinskey ME, Sekhar LN, Hirsch W Jr, Yonas H, Horton JA. Aneurysms of the intracavernous carotid artery: clinical presentation, radiographic features, and pathogenesis. Neurosurgery. 1990 Jan:26(1):71-9 [PubMed PMID: 2294481]

Ringer AJ, Salud L, Tomsick TA. Carotid cavernous fistulas: anatomy, classification, and treatment. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2005 Apr:16(2):279-95, viii [PubMed PMID: 15694161]

Xiong M, Moy WL. Orbital Apex Syndrome Resulting from Mixed Bacterial Sphenoid Sinusitis. European journal of case reports in internal medicine. 2018:5(7):000905. doi: 10.12890/2018_000905. Epub 2018 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 30756053]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeferman CE, Ciubotaru AD, Ghiciuc CM, Stoica BA, Gradinaru I. A systematic review of orbital apex syndrome of odontogenic origin: Proposed algorithm for treatment. European journal of ophthalmology. 2021 Jan:31(1):34-41. doi: 10.1177/1120672120954042. Epub 2020 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 32927961]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHung YC, Chiu M, Elder MJ. Bilateral orbital apex syndrome secondary to sinusitis. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2019 Aug:47(6):806-807. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13497. Epub 2019 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 30859705]

Ronen JA, Malik FA, Wiechmann C, Kolli S, Nwojo R. More than Meets the Eye: Aspergillus-Related Orbital Apex Syndrome. Cureus. 2020 Jul 23:12(7):e9352. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9352. Epub 2020 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 32850224]

Kocaoğlu G, Utine CA, Yaman A, Men S. Orbital Apex Syndrome Secondary to Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus. Turkish journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Feb:48(1):42-46. doi: 10.4274/tjo.02256. Epub 2018 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 29576898]

Fukushima A, Mihoshi M, Shimizu Y, Tabuchi H. A Case of Orbital Apex Syndrome Related to Herpes Zoster Ophtalmicus. Cureus. 2022 Jul:14(7):e27254. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27254. Epub 2022 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 36039197]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChang CC, Chang YC, Su KY, Lee YC, Chang FL, Li MH, Chen YC, Chen N. Acute Orbital Apex Syndrome Caused by Idiopathic Sclerosing Orbital Inflammation. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Dec 1:12(12):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12123003. Epub 2022 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 36553010]

Li Y, Lip G, Chong V, Yuan J, Ding Z. Idiopathic orbital inflammation syndrome with retro-orbital involvement: a retrospective study of eight patients. PloS one. 2013:8(2):e57126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057126. Epub 2013 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 23437329]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDutta P, Anand K. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome: A Review of Diagnostic Criteria and Unresolved Issues. Journal of current ophthalmology. 2021 Apr-Jun:33(2):104-111. doi: 10.4103/joco.joco_134_20. Epub 2021 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 34409218]

Shokri T, Zacharia BE, Lighthall JG. Traumatic Orbital Apex Syndrome: An Uncommon Sequela of Facial Trauma. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2019 Dec:98(10):609-612. doi: 10.1177/0145561319860526. Epub 2019 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 31266402]

Talwar AA, Ricci JA. A Meta-Analysis of Traumatic Orbital Apex Syndrome and the Effectiveness of Surgical and Clinical Treatments. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2021 Sep 1:32(6):2176-2179. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007629. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33770036]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJin H, Gong S, Han K, Wang J, Lv L, Dong Y, Zhang D, Hou L. Clinical management of traumatic superior orbital fissure and orbital apex syndromes. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2018 Feb:165():50-54. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.12.022. Epub 2017 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 29306766]

Munawar K, Nayak G, Fatterpekar GM, Sen C, Zagzag D, Zan E, Hagiwara M. Cavernous sinus lesions. Clinical imaging. 2020 Dec:68():71-89. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.06.029. Epub 2020 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 32574933]

McClelland C, Manousakis G, Lee MS. Progressive External Ophthalmoplegia. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2016 Jun:16(6):53. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0652-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27072953]

Warburton RE, Brookes CC, Golden BA, Turvey TA. Orbital apex disorders: a case series. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2016 Apr:45(4):497-506. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.10.014. Epub 2015 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 26725107]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence