Introduction

Fractures of the clavicle are quite common, accounting for up to 10% of all fractures[1]. It is the most common fracture of childhood. A fall onto the lateral shoulder most frequently causes a clavicle fracture. Radiographs confirm the diagnosis and aid in further evaluation and treatment. While most clavicle fractures are treated conservatively, severely displaced or comminuted fractures may require surgical fixation.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

In 87% of reported cases, a clavicle fracture results from a fall directly onto the lateral shoulder. Less commonly, fractures may result from direct trauma to the clavicle or from a fall onto an outstretched hand.

Epidemiology

Clavicle fractures represent 2% to 10% of all fractures. Clavicle fractures affect 1 in 1000 people per year. They are the most common fractures during childhood, and approximately two-thirds of all clavicle fractures occurring in males. There is a bimodal distribution of clavicle fractures, with the 2 peaks being men younger than 25 (sports injuries) and patients older than 55 years of age (falls).[2] Aapproximately 20 percent of females and more than one-third of males with claviclular fractures are between 13-20 years old.[3]

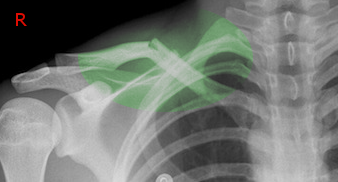

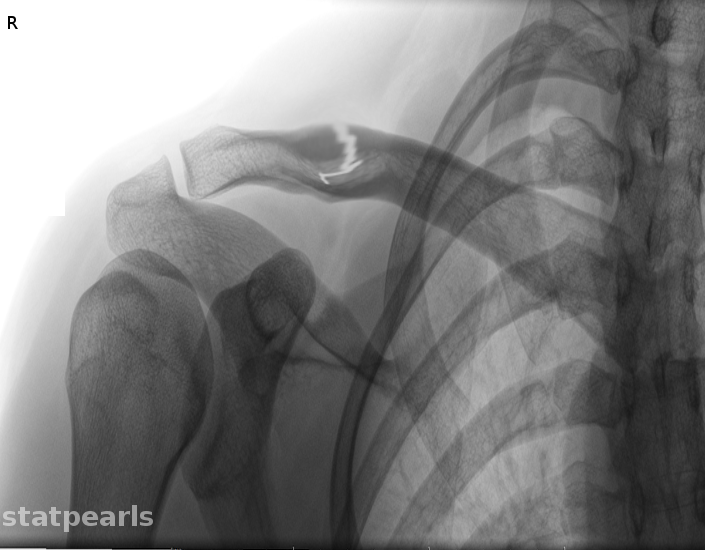

The middle third of the clavicle is fractured in 69% of cases, the distal third is fractured in 28% of cases, and the proximal third is fractured in 3% of cases.[3]

Pathophysiology

The clavicle is an S-shaped bone and is the only osseous link between the upper extremity and the trunk. The clavicle articulates distally with the acromion at the acromioclavicular joint and articulates proximally with the sternum at the sternoclavicular joint. Due to its superficial subcutaneous location and the numerous ligamentous and muscular forces applied to it, the clavicle is easily fractured. Because the midshaft of the clavicle is the thinnest segment and does not contain ligamentous attachments, it is the most easily fractured location.

Fractures of the clavicle are typically described using the Allman classification system, dividing the clavicle into 3 groups based on location. Fractures of the middle third or midshaft fractures are in Group I (the most common), fractures of the distal or lateral third are in Group II, and fractures of the proximal or medial third are in Group III.[7]

The Allman classification has been further revised by Neer and includes the following:[8]

- Type 1 fracture where there is minimal displacement. These fractures occur just lateral to the intact coracoclavicular ligament and are managed non-surgically.

- Type 2 fracture occurs when the medial fragment is separated from the coracoclavicular complex. The fragment is displaced inferiorly due to the pull of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The distal fragment is displaced cranially. This fracture results in an obvious deformity and has a high rate of nonunion.

- Type 3 fracture is where there is non-displacement of the fracture but it extends into the acromioclavicular joint. Again, these fractures are treated non-surgically. However, late AC degenerative changes can occur and may require excision of the distal clavicular segment.

Many important structures are adjacent to the clavicle and thus subject to injury when a fracture occurs. The subclavian artery passes anterior to the first rib and is in close proximity with the middle segment of the clavicle. In addition, the brachial plexus also course behind the clavicle and are at risk when there is a fracture of the middle clavicle.

More than 85 percent of clavicular fractures occur by a fall onto the shoulder[9]. Most of these fractures among the young occur in a traffic accident or a sports injury[3]. Approximately 40 percent of injuries caused by traffic accidents occur in cyclists, more than 25 percent in car drivers or passengers, 17 percent in motorcyclists, and 17 percent in pedestrians[3]. There seems to be no correlation between the clavicular fracture site and the mechanism of injury[9]. Clavicle fractures do occur in isolation but when there is a high energy injury one should always look for associated injuries like a pneumothorax, hemothorax, and head trauma.

History and Physical

Patients with clavicle fractures typically present with well-localized pain over the fracture site. The affected extremity is typically held close to the body. Patients may report a snapping or cracking sound when the injury occurs. The most common reported mechanism is a fall onto the lateral shoulder. A direct blow to the clavicle or a fall on an outstretched hand are less common mechanisms.

On physical examination, the patient may present with a visible or palpable deformity over the fracture site. The shoulder is typically pulled downward in patients with fractures of the middle third of the clavicle, due to the effect of the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi muscles on the distal fragment. The sternocleidomastoid displaces the proximal fragment upward. There may be localized tenderness, crepitus, ecchymoses, or edema over the clavicle. Severe angulation or displacement of the fracture may result in the tenting of the skin, which signifies a high risk for it to develop into an open fracture.

Because of the proximity of the brachial plexus and subclavian vessels to the clavicle, it is important to perform a complete neurovascular examination. Decreased distal pulses, discoloration, or edema may be present in a subclavian vessel injury. Brachial plexus injury may result in distal neurologic findings. A complete lung examination should also be performed, as rarely there may be an injury to the lung apex, resulting in pneumothorax or hemothorax. Shortness of breath or diminished breath sounds may be a clinical clue. Palpation of the surrounding ribs and scapula should be performed to evaluate for possible associated rib or scapular fractures.

Repetitive stress on proximal clavicle from different activities may lead to a stress fracture in patients with no history of acute trauma.[10], [11], [12]

Evaluation

A standard anteroposterior clavicle radiograph should be obtained in all patients who present with an injury to the clavicle. A second 45-degree cephalic tilt view radiograph improves the assessment of the degree of clavicle displacement. This additional view also minimizes the overlap of the first rib and scapula. While most clavicle fractures are visible using these views, a CT scan may be necessary to guide treatment in the less frequent proximal or distal fractures to evaluate intra-articular involvement.[13] An expiratory posteroanterior chest radiograph should be obtained if there is a clinical concern for possible pneumothorax or rib injury. If there is a concern for neurovascular injury, arteriography, ultrasonography, and CT may be used to guide further management.

Evaluation of the proximal clavicular stress fractures begins with plain radiographic views and a CT scan when necessary. Further imaging may be required to rule out inflammation and neoplasia in patients with radiographic and clinical evidence of swelling around this area.

Treatment / Management

Immediate orthopedic consultation should be obtained for patients with neurovascular compromise, open fractures, tenting of the skin, severe angulation or displacement or any break in the skin near the fracture, which are absolute indications for surgery. Relative surgery indications include Neer Type II displaced distal-third fractures, fracture-shortening above 1.5 cm, or 15% of the contralateral side, floating shoulder, polytrauma, significant seizure or neuromuscular disorder, and cosmetic issues due to displacement.[14], [15], [16] After a complete evaluation of possible associated injuries and ruling out indications for surgery, the mainstay of treatment of clavicle fractures is analgesia, immobilization, and proper orthopedic follow-up.

In group I midshaft clavicle fractures, conservative nonoperative management is the most common approach. Treatment of these fractures consists of supportive or reductive measures. Supportive treatment involves the placement of a sling or sling and swathe, while reductive treatment includes the use of a figure-of-eight brace. Similar union rates have been achieved using either method. In uncomplicated nondisplaced midshaft fractures, patients treated nonoperatively with these conservative measures have fewer complications and a faster recovery then those treated operatively. However, in patients with a higher risk of nonunion (due to fracture displacement, clavicle shortening, or fracture comminution) surgical fixation results in improved patient outcomes relative to nonoperative management. Surgical fixation is achieved with open reduction with plate fixation or intramedullary fixation.[17]

In group II distal clavicle fractures, patients should be immobilized with a simple sling or sling and swathe. Figure-of-eight braces should be avoided, as they may increase the displacement of the fracture. Because nonunion is seen in approximately 30% of cases, an orthopedic referral is necessary. Definitive treatment is controversial, with some studies showing improved outcomes with surgical fixation while others show similar outcomes in patients managed nonoperatively.

Nondisplaced, proximal, group III clavicle fractures are treated conservatively, with a sling used for support and comfort. Analgesics and early range of motion are encouraged. Significantly displaced proximal clavicle fractures are rare secondary to strong ligamentous support. Serious associated injuries are found in approximately 90% of displaced proximal clavicle fractures. If signs of neurovascular compromise exist, displaced proximal fractures should be immediately reduced. These patients should carefully be evaluated for severe intrathoracic injury.[18]

Treatment for children is similar to adults. Because of the great periosteal regeneration potential in children, healing occurs more quickly than in adults. Callus formation can be prominent in children, and parents should be educated on this normal finding.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a clavicle fracture includes acromioclavicular joint injury, rib fracture, scapular fracture, shoulder dislocation, rotator cuff injury, and sternoclavicular joint injury. Possible complications of clavicle fractures must also be fully evaluated, including pneumothorax, brachial plexus injury, and subclavian vessel injury. An inflammatory or neoplastic process could mimic a clavicular stress fracture.

Prognosis

The prognosis of the majority of clavicle fractures is good. Most clavicle fractures are treated conservatively and nonoperatively. Patients are immobilized in a sling or figure-of-eight brace until the clinical union is achieved. This typically occurs by 6 to 12 weeks in adults and 3 to 6 weeks in children. Patients should perform a range of motion and strengthen exercises under the care of physical therapy once immobilization is no longer necessary. Patients typically may resume full daily activity approximately 6 weeks after injury. Requiring 2 to 4 months of rehabilitation, return to full contact sports requires the athlete should demonstrate radiographic evidence of bony healing, no tenderness to palpation, a full range of motion, and normal shoulder strength.

Complications

In fractures of the clavicle, serious complications are rare. Brachial plexus injury or injury to the subclavian vessels can occur at the time of presentation or during the healing and callus formation of the clavicle. Excessive callus formation can lead to compression of the brachial plexus, resulting in peripheral neuropathy.

The most common complication of clavicle fractures is malunion, or when the clavicle fracture heals with angulation, shortening, or a poor cosmetic appearance. Patients with malunion of clavicle fractures typically have except full function and are clinically not significant. Some malunions may cause neurologic or functional problems, especially if there is a shortening greater than 2 cm.[19] In patients with continued pain, decreased range of motion, or decreased strength secondary to the malunion, delayed surgical correction may be considered.

Nonunion is the failure of the fracture to heal in 4 to 6 months. In middle-third clavicle fractures, the nonunion rate for all fractures treated nonoperatively is 6%, increasing to 15% in displaced fractures. Nonunion rates for distal third clavicle fractures range from 28% to 44%. Risk factors for nonunion include advanced age, female gender, smoking, significant displacement or shortening of fracture, fracture comminution, and inadequate immobilization. Many patients with clavicle fracture nonunion are asymptomatic and do not require any further treatment. Other symptomatic clavicle fracture nonunion patients may have continued pain, loss of range of motion, or loss of function. These patients should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon for further surgical management.[20]

Proximal-third clavicle fracture complications include nonunion and posttraumatic arthritis. Acutely, proximal clavicle fractures displaced inwardly may result in severe intrathoracic injuries, including brachial plexus injury, subclavian vessel injury, and pneumothorax.[21] Fractures of the distal third of the clavicle have the highest incidence of nonunion; however, many of these patient's nonunions are asymptomatic.[22] Degenerative arthritis within the acromioclavicular joint can be a late complication.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with clavicular fractures are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an orthopedic surgeon, emergency department physician, primary care provider, nurse practitioner, and a physical therapist. Most patients with clavicular fracture first present to the emergency department and it is important to consult with the radiologist for the appropriate imaging studies. A thorough neurovascular and lung exam is necessary. The majority of clavicular fractures are managed with conservative care.[23][24] However, immediate orthopedic consultation should be obtained for patients with neurovascular compromise, open fractures, tenting of the skin, or any break in the skin near the fracture.[25][26]

The orthopedic nurse should inform the patient that a visible prominence may be present for months and it is a normal part of healing. If the patient continues to have pain and difficulty with motion, then nonunion should be suspected. The patient should be educated that return to sports should only take place after complete healing has occurred. The healing of the fracture may take 8-12 weeks and most patients have a good outcome. However, a few patients may have chronic pain and limited range of motion of the shoulder.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ropars M, Thomazeau H, Huten D. Clavicle fractures. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2017 Feb:103(1S):S53-S59. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2016.11.007. Epub 2016 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 28043849]

Wiesel B, Nagda S, Mehta S, Churchill R. Management of Midshaft Clavicle Fractures in Adults. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2018 Nov 15:26(22):e468-e476. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00442. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30180095]

Robinson CM. Fractures of the clavicle in the adult. Epidemiology and classification. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1998 May:80(3):476-84 [PubMed PMID: 9619941]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHughes K, Kimpton J, Wei R, Williamson M, Yeo A, Arnander M, Gelfer Y. Clavicle fracture nonunion in the paediatric population: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of children's orthopaedics. 2018 Feb 1:12(1):2-8. doi: 10.1302/1863-2548.12.170155. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29456747]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBan I, Troelsen A. Risk profile of patients developing nonunion of the clavicle and outcome of treatment--analysis of fifty five nonunions in seven hundred and twenty nine consecutive fractures. International orthopaedics. 2016 Mar:40(3):587-93. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3120-8. Epub 2016 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 26847264]

Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Wakefield AE. Estimating the risk of nonunion following nonoperative treatment of a clavicular fracture. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2004 Jul:86(7):1359-65 [PubMed PMID: 15252081]

Allman FL Jr. Fractures and ligamentous injuries of the clavicle and its articulation. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1967 Jun:49(4):774-84 [PubMed PMID: 6026010]

Neer CS 2nd. Fractures of the distal third of the clavicle. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1968 May-Jun:58():43-50 [PubMed PMID: 5666866]

Stanley D, Trowbridge EA, Norris SH. The mechanism of clavicular fracture. A clinical and biomechanical analysis. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1988 May:70(3):461-4 [PubMed PMID: 3372571]

Abbot AE, Hannafin JA. Stress fracture of the clavicle in a female lightweight rower. A case report and review of the literature. The American journal of sports medicine. 2001 May-Jun:29(3):370-2 [PubMed PMID: 11394611]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFallon KE, Fricker PA. Stress fracture of the clavicle in a young female gymnast. British journal of sports medicine. 2001 Dec:35(6):448-9 [PubMed PMID: 11726488]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePeebles CR, Sulkin T, Sampson MA. 'Cable-maker's clavicle': stress fracture of the medial clavicle. Skeletal radiology. 2000 Jul:29(7):421-3 [PubMed PMID: 10963430]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSambandam B, Gupta R, Kumar S, Maini L. Fracture of distal end clavicle: A review. Journal of clinical orthopaedics and trauma. 2014 Jun:5(2):65-73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2014.05.007. Epub 2014 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 25983473]

Pandya NK, Namdari S, Hosalkar HS. Displaced clavicle fractures in adolescents: facts, controversies, and current trends. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2012 Aug:20(8):498-505. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-498. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22855852]

Zenni EJ Jr, Krieg JK, Rosen MJ. Open reduction and internal fixation of clavicular fractures. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1981 Jan:63(1):147-51 [PubMed PMID: 7451517]

Fanter NJ, Kenny RM, Baker CL 3rd, Baker CL Jr. Surgical treatment of clavicle fractures in the adolescent athlete. Sports health. 2015 Mar:7(2):137-41. doi: 10.1177/1941738114566381. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25984259]

Coppa V, Dei Giudici L, Cecconi S, Marinelli M, Gigante A. Midshaft clavicle fractures treatment: threaded Kirschner wire versus conservative approach. Strategies in trauma and limb reconstruction. 2017 Nov:12(3):141-150. doi: 10.1007/s11751-017-0293-7. Epub 2017 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 28825169]

Anderson K. Evaluation and treatment of distal clavicle fractures. Clinics in sports medicine. 2003 Apr:22(2):319-26, vii [PubMed PMID: 12825533]

McKee MD, Wild LM, Schemitsch EH. Midshaft malunions of the clavicle. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2003 May:85(5):790-7 [PubMed PMID: 12728026]

Luo TD, Ashraf A, Larson AN, Stans AA, Shaughnessy WJ, McIntosh AL. Complications in the treatment of adolescent clavicle fractures. Orthopedics. 2015 Apr:38(4):e287-91. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20150402-56. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25901621]

Bishop JY, Flatow EL. Pediatric shoulder trauma. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2005 Mar:(432):41-8 [PubMed PMID: 15738802]

Banerjee R, Waterman B, Padalecki J, Robertson W. Management of distal clavicle fractures. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2011 Jul:19(7):392-401 [PubMed PMID: 21724918]

Vautrin M, Kaminski G, Barimani B, Elmers J, Philippe V, Cherix S, Thein E, Borens O, Vauclair F. Does candidate for plate fixation selection improve the functional outcome after midshaft clavicle fracture? A systematic review of 1348 patients. Shoulder & elbow. 2019 Feb:11(1):9-16. doi: 10.1177/1758573218777996. Epub 2018 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 30719093]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLenza M, Buchbinder R, Johnston RV, Ferrari BA, Faloppa F. Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating fractures of the middle third of the clavicle. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2019 Jan 22:1(1):CD009363. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009363.pub3. Epub 2019 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 30666620]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCalbiyik M, Taskoparan M, Ipek D. Surgical treatment of displaced clavicle fractures with a novel intramedullary device; comparison of less-invasive versus standard technique. Acta orthopaedica Belgica. 2018 Sep:84(3):331-337 [PubMed PMID: 30840576]

Dong WW, Zhao X, Mao HJ, Yao LW. [Minimally-invasive internal fixation for mid-lateral 1/3 clavicle fracture with distal clavicular anatomic locking plate]. Zhongguo gu shang = China journal of orthopaedics and traumatology. 2019 Jan 25:32(1):28-32. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-0034.2019.01.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30813664]