Introduction

Ocular biometry refers to the measurement of anatomical dimensions of the eye, which include corneal curvature (keratometry), axial length, and anterior chamber depth. These measurements are primarily used to calculate the appropriate power of the intraocular lens (IOL) to be implanted during cataract surgery.[1]

Given the technological advances in cataract surgery, and the introduction of premium intraocular lens implants, patient expectations continue to rise, and refractive error following cataract surgery is no longer tolerated. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to obtain accurate biometric readings to optimize postoperative refractive outcomes.[2]

This article will discuss the different modalities used for ocular biometry, the biometric parameters that are important for calculating the intraocular lens implant, and the variables that can affect the accuracy of the measurements.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Biometry is performed during the pre-operative assessment for all patients undergoing cataract surgery. The measurements obtained are used to calculate the appropriate intraocular lens for each patient. Since its inception, the formula for calculating lens power has evolved, with numerous proposed formulas. One classic formula is the SRK formula, which was developed by Sanders, Retzlaff, and Kraff.[3] This formula uses two biometric values, the axial length and the corneal power, to calculate the intraocular lens power. The SRK formula is stated in the following format:

- P = A – 0.9 K – 2.5 AL

A is the A constant, K is the average keratometry value in diopters, and the AL is the axial length in millimeters (mm).

The A-constant is a theoretical value that relates the lens power to the axial length and keratometry. It is a value specific to the lens manufacturer and type and varies depending on multiple factors, including refraction index and placement within the eye. The A-constant varies approximately in a 1-to-1 ratio with the power of the lens.[2]

Keratometry is the measurement of the power of the cornea, which is based on the corneal curvature. This measurement (expressed in diopters) can be accomplished with either a manual or automated keratometer. In keratometry, the cornea is assumed to be a spherocylinder with a fixed ratio between the anterior and posterior corneal curvature.[4] The cornea then serves as a convex mirror, which leads to a virtual image from which the anterior corneal curvature is calculated based on the 3 mm diameter mid-peripheral zone area.[3]

Keratometers are limited in accurately measuring the power of the cornea because they do not directly measure the posterior corneal curvature, and they are not able to accurately measure the central zone of effective corneal power, which is of particular concern in patients who have undergone keratorefractive surgery.[5] Topography is a corneal map that utilizes Scheimpflug principles to measure the anterior and posterior radii of corneal curvature, the corneal thickness, and the corneal power in diopters.[4] However, detailed discussions of corneal power measurements are beyond the scope of this article.

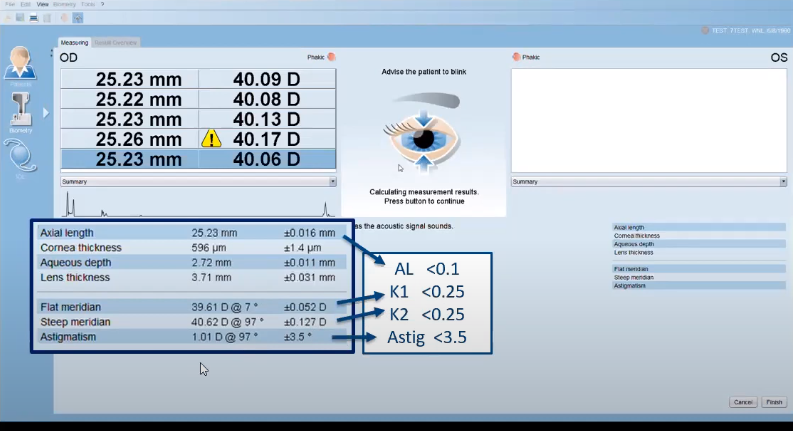

The axial length, measured in millimeters, is defined as the distance from the anterior surface of the cornea to the retinal pigment epithelium. The axial length can be measured using either ultrasound biometry (accomplished via direct contact or immersion) or optical biometry.

The SRK formula is useful for illustrating the relationships of different variables that contribute to the refractive state. However, newer formulas have been developed to measure IOL power. These formulas consider additional variables such as anterior chamber depth and lens thickness to estimate the effective lens position (ELP), a parameter that leads to improved accuracy in IOL selection.[3]

Accurately measuring the axial length is crucial, as a 1 mm error can change the IOL power by nearly 2.5 times. Two main methods are used to measure the axial length; ultrasound biometry and optical biometry.

Clinical Significance

Ultrasound Biometry

Ultrasound biometry uses a high-frequency sound wave generated by a handheld probe to measure the axial length of the eye and various internal structures. The sound wave travels through the eye from anterior to posterior, passing through the cornea, anterior chamber, lens, and vitreous before reaching the retina. These different structures manifest as sharp spikes on the A-scan, with the initial spike being the probe tip on the surface of the cornea, followed by the anterior lens capsule, posterior lens capsule, retina, sclera, and the orbital fat. (Figure 1)

When the spikes are high and steep, the ultrasound beam is on the axis. If the sclera or orbital fat spikes are absent, the ultrasound beam is likely aligned with the optic nerve rather than the macula, and adjustment of the probe is necessary. The machine subsequently measures the transit time of the wave as it deflects from the internal structures of the eye. By assuming the velocity of the sound wave, the total distance traveled, which is the eye’s axial length, can be calculated.[6][7]

In addition to the axial length, ultrasound biometry can measure the anterior chamber depth and the lens thickness. Ultrasound biometry does not provide keratometry measurements, so corneal power must be measured with a keratometer or topographer to calculate the IOL power.

There are two types of ultrasound biometry available; contact type and immersion type. Contract ultrasound biometry involves placing a probe directly onto the cornea. After administering topical anesthetic drops, the user must align the probe with the visual axis without applying pressure onto the cornea. A misaligned probe or inadvertent compression of the cornea may result in axial length measurements that are too low and, as such, an intraocular lens power that is too high. Because the probe is in direct contact with the eye, there is a potential risk of transmitting infection if it is not properly sanitized between patients.

Immersion ultrasound biometry involves placing a scleral shell filled with saline between the probe and the eye. Axial length measured with immersion may be more reliable than contact ultrasound because there is no risk of corneal compression. However, proper alignment is still necessary for accurate results. Some studies have found immersion to be more accurate than contact biometry - likely because it is not prone to compression errors.[8] However, other studies have found no difference between the two.[9] Because the probe does not come into direct contact with the eye, the risk of infection is negligible.

Optical Biometry

Optical biometry is a non-contact automated modality used for measuring optical biometric parameters. Two models are widely available that employ two different techniques: Laser partial coherence interferometry (PCI) and optical low-coherence reflectometry (OLCR).[10][11] Both techniques carry the advantage of performing keratometry in addition to measuring the axial length.

The PCI uses a 780 nm infrared laser in a dual-beam setup. In this setup, the eye and the photodetector are located at each leg of the interferometer, and both partial beams are reflected at the corneal surface and the retinal pigment epithelium. (Figure 2) Interference will occur if the path difference between the beams is smaller than the coherence length, and the photodetector will detect this interference signal. Because the position of the interferometer mirror is known, the machine can measure the optical length between the corneal surface and the retina. It can then derive the geometric intraocular distance based on the refractive indices of the ocular media (cornea, aqueous, lens, vitreous humor), with a resulting resolution of 12 microns.[12][13]

The OLCR uses an 820 nm superluminescent diode in a standard Michelson interferometer setup. (Figure 3) In this biometer, the optical-path-length measurements are aligned on the visual axis of the patient’s eye, and a specialized rotating glass system embedded in the machine changes the optical path length. Doing so measures not only the axial length and corneal curvature but also the central corneal thickness, lens thickness, retinal thickness, and pupil diameter.[14]

Because the OLCR-based device takes more anatomic measurements, the process takes twice as long as the PCI-based device.[15][16] Another important point differentiating PCI from OLCR is how the anterior chamber depth is measured. In the OLCR-based device, ACD is measured as the distance from the corneal endothelium to the anterior lens surface, whereas the PCI-based device measures ACD from the corneal epithelium to the anterior lens surface. Therefore, clinicians should note that the measurements among different machines may not be interchangeable.

Since the introduction of optical biometry, numerous studies have compared the different methods. In one study, both the OCLR-based and the PCI-based devices had comparable performances in determining the axial length and keratometry.[17] Another study that compared optical biometry to traditional ultrasound found no statistically significant differences in axial length measurements and anterior chamber depth but found that optical biometry was easier to use than ultrasound biometry.[18]

Other advantages of optical biometry result from its non-contact methodology; the risk of patient cross-contamination is eliminated, and there is no need for topical anesthesia. Unlike ultrasound biometry, optical biometry performs keratometry, so additional instrumentation is not necessary when calculating the IOL power.

There are situations in which the ultrasound method is preferred. Because both the PCL-based device and the OLCR-based devices require an adequate foveal fixation for optimal alignment, eyes with a visual acuity of worse than 20/200, corneal scarring, macular degeneration, and eccentric fixation can all lead to inaccurate measurements. Additionally, optical biometry provides less accurate axial length measurements in eyes with very dense or posterior subcapsular cataracts because the laser beams do not penetrate the lens as well as the ultrasound waves. Ultrasound biometry, therefore, is not obsolete and should be considered to be complementary to optical biometry.[13]

Ever since Harold Ridley implanted the first intraocular lens in 1949, cataract surgery has continued to advance. The development of optical biometry combined with improved formulae for calculating IOL power has allowed for precise refractive outcomes. The goal of surgery is no longer simply to achieve the functional vision but rather to achieve the ideal post-operative refractive state based on patient preferences and expectations. Biometry is performed during the pre-operative assessment for all patients evaluated for cataract surgery. While optical biometry has become the mainstay in modern ophthalmology, ultrasound biometry plays a role in certain situations.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ever since the first intraocular lens was implanted in 1949, cataract surgery has continued to advance, and patient expectations continue to rise. Accurate biometric readings are crucial for achieving the best refractive outcome. An interprofessional team of ophthalmologists and ophthalmic technicians may play a role during the cataract pre-operative assessment.

A detailed medical and ophthalmic history is essential, as certain conditions may affect the choice of biometer used or the accuracy of the results. All members of the practice should understand the advantages, limitations, and clinical indications for each modality. Understanding the technical factors that contribute to inaccurate readings, such as corneal compression and probe misalignment, is especially important for technicians.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sahin A, Hamrah P. Clinically relevant biometry. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2012 Jan:23(1):47-53. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834cd63e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22081032]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOlsen T. Calculation of intraocular lens power: a review. Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2007 Aug:85(5):472-85 [PubMed PMID: 17403024]

Retzlaff J. A new intraocular lens calculation formula. Journal - American Intra-Ocular Implant Society. 1980 Apr:6(2):148-52 [PubMed PMID: 7410163]

Sridhar MS. Anatomy of cornea and ocular surface. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Feb:66(2):190-194. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_646_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29380756]

Holladay JT, Hill WE, Steinmueller A. Corneal power measurements using scheimpflug imaging in eyes with prior corneal refractive surgery. Journal of refractive surgery (Thorofare, N.J. : 1995). 2009 Oct:25(10):862-8. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20090917-07. Epub 2009 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 19835326]

JANSSON F, KOCK E. Determination of the velocity of ultrasound in the human lens and vitreous. Acta ophthalmologica. 1962:40():420-33 [PubMed PMID: 13957440]

Olsen T. Theoretical approach to intraocular lens calculation using Gaussian optics. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 1987 Mar:13(2):141-5 [PubMed PMID: 3572769]

Giers U, Epple C. Comparison of A-scan device accuracy. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 1990 Mar:16(2):235-42 [PubMed PMID: 2329484]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHennessy MP, Franzco, Chan DG. Contact versus immersion biometry of axial length before cataract surgery. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2003 Nov:29(11):2195-8 [PubMed PMID: 14670431]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDrexler W, Findl O, Menapace R, Rainer G, Vass C, Hitzenberger CK, Fercher AF. Partial coherence interferometry: a novel approach to biometry in cataract surgery. American journal of ophthalmology. 1998 Oct:126(4):524-34 [PubMed PMID: 9780097]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBuckhurst PJ, Wolffsohn JS, Shah S, Naroo SA, Davies LN, Berrow EJ. A new optical low coherence reflectometry device for ocular biometry in cataract patients. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2009 Jul:93(7):949-53. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.156554. Epub 2009 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 19380310]

Santodomingo-Rubido J, Mallen EA, Gilmartin B, Wolffsohn JS. A new non-contact optical device for ocular biometry. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2002 Apr:86(4):458-62 [PubMed PMID: 11914218]

Rajan MS, Keilhorn I, Bell JA. Partial coherence laser interferometry vs conventional ultrasound biometry in intraocular lens power calculations. Eye (London, England). 2002 Sep:16(5):552-6 [PubMed PMID: 12194067]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchmid GF. Axial and peripheral eye length measured with optical low coherence reflectometry. Journal of biomedical optics. 2003 Oct:8(4):655-62 [PubMed PMID: 14563204]

Chen YA, Hirnschall N, Findl O. Evaluation of 2 new optical biometry devices and comparison with the current gold standard biometer. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2011 Mar:37(3):513-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.10.041. Epub 2011 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 21244866]

Prager TC, Hardten DR, Fogal BJ. Enhancing intraocular lens outcome precision: an evaluation of axial length determinations, keratometry, and IOL formulas. Ophthalmology clinics of North America. 2006 Dec:19(4):435-48 [PubMed PMID: 17067899]

Holzer MP, Mamusa M, Auffarth GU. Accuracy of a new partial coherence interferometry analyser for biometric measurements. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2009 Jun:93(6):807-10. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.152736. Epub 2009 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 19289385]

Montés-Micó R, Carones F, Buttacchio A, Ferrer-Blasco T, Madrid-Costa D. Comparison of immersion ultrasound, partial coherence interferometry, and low coherence reflectometry for ocular biometry in cataract patients. Journal of refractive surgery (Thorofare, N.J. : 1995). 2011 Sep:27(9):665-71. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20110202-01. Epub 2011 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 21323302]