Introduction

Skin neoplasms are one of the most common diagnoses among patient encounters.[1] Evaluating both benign and malignant neoplasms is vital, particularly due to the increasing incidence of skin cancers and complications associated with the condition.[2][3] Skin cancer has multiple etiologic factors, with UV radiation-induced DNA damage and oncogenesis being the most prominent. Preventive strategies, such as sunscreen application, are essential in reducing risk.[4] After evaluation by a trained healthcare provider, a biopsy is typically performed, and histopathological evaluation helps confirm the diagnosis and differentiate the type of skin cancer from other conditions.[5] Management of skin cancer may involve observation, topical therapies, local non-topical treatments (eg, antineoplastic medication injections), systemic regimens (eg, chemotherapy and immunotherapy), radiation therapy, and surgical or procedural interventions (eg, Mohs micrographic surgery and cryosurgery).

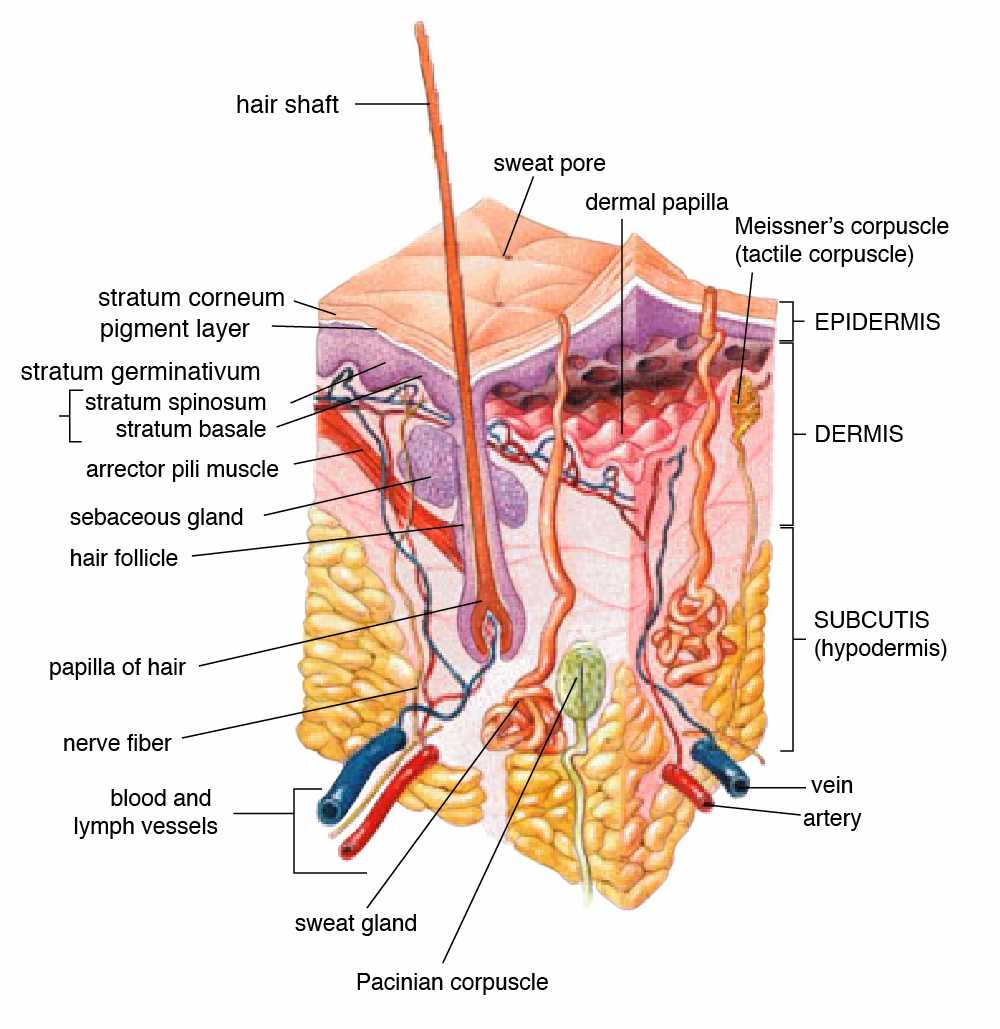

The skin's anatomical complexity allows skin cancer to arise from any of its cells or components. The proliferation of cells in skin cancer can be benign or malignant (see Image. Anatomy of the Human Skin). Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Anatomy, Skin (Integument)," for more information on skin anatomy. In standard literature, malignant skin cancer is typically categorized into melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, which usually refer to basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. However, this classification can be problematic, as skin cancer can originate from various cells and subdivisions of the skin.

Benign epidermal tumors may include epidermal nevi, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (eg, prurigo nodularis), and acanthomas (eg, seborrheic keratosis). Premalignant dysplasia, such as actinic keratosis and arsenical keratosis, may also be present. Malignant tumors of the epidermis include intraepidermal carcinoma (eg, Bowen disease), basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and verrucous carcinoma. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Seborrheic Keratosis," "Clear Cell Acanthoma," "Cutaneous Horn," "Keratoacanthoma," "Cutaneous Melanoacanthoma," "Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma," "Intraepidermal Carcinoma," and "Basal Cell Carcinoma," for more information on common epidermal tumors.

Pigmentary lesions include those with basal melanocytic proliferation (eg, solar lentigo), junctional or dermal melanocytic lesions (eg, Spitz nevus), dysplastic lesions (eg, dysplastic nevus), and malignant lesions (eg, melanoma, clear cell sarcoma). Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Subungual Melanoma," "Lentigo Maligna Melanoma," "Metastatic Melanoma," "Dysplastic Nevi," "Atypical Mole," "Acral Lentiginous Melanoma," and "Congenital Melanocytic Nevi," for more information on pigmentary lesions relevant to skin cancer.

Skin cancer may arise from cutaneous appendages, such as hair follicles (eg, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma), sebaceous glands (eg, sebaceous adenoma and sebaceous carcinoma), apocrine glands (eg, spiradenoma), and eccrine glands (eg, porocarcinoma). Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma," "Sebaceous Carcinoma," "Syringoma," "Spiradenoma," "Trichoblastoma and Trichoepithelioma," and "Cylindroma," for more information on tumors of cutaneous appendages.

Fibrous tissues of the skin can also proliferate, leading to skin cancer, such as dermatofibroma and its malignant counterpart, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans" and "Dermatofibroma," for more information on fibrous tumors.

The presence of fat, muscle, cartilage, and bone can lead to skin cancers such as liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, chondroma, and osteosarcoma (although osteosarcoma may be considered metastatic by some). Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Atypical Fibroxanthoma" and "Leiomyosarcoma," for more information on fat, muscle, cartilage, and bone tumors.

Benign and malignant skin cancers can arise from neural tissue, such as Merkel cell carcinoma and schwannoma, or from vascular tissue, such as hemangioma and angiosarcoma. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Angiolymphoid Hyperplasia With Eosinophilia," "Angiosarcoma," "Merkel Cell Carcinoma of the Skin," "Neurothekeoma," "Hemangioma," "Cutaneous Vascular Malignancies," "Angiosarcoma," " Kaposi Sarcoma," and "Cutaneous Angiofibroma," for more information on common tumors of neural and vascular origin.

Infiltrative skin cancers can arise from various immune cells that reside in the skin, including mastocytoma, xanthoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, T-cell lymphoma, natural killer (NK)—cell lymphoma, and B-cell lymphoma. Please see StatPearls' companion resources "Sezary Syndrome," "Extranodal NK-Cell Lymphoma," "Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma," "Dermatopathology Evaluation of Cysts," "Mastocytoma," "Mycosis Fungoides," and "Lymphomatoid Papulosis," for more information.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of skin cancer varies depending on the type of cancer. UV radiation is a major etiologic factor for most nonmelanoma skin cancers, including squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma, as well as melanoma.[6][7][8] Along with chemical carcinogens and wound-related changes, UV radiation is believed to damage DNA, which results in mutations in tumor suppressor genes (eg, p53) and genomic instability.[9][10][11] Most cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (90%) exhibit UV-induced p53 gene mutations, leading to the uncontrolled proliferation of keratinocytes.[12] Mutations implicated in basal cell carcinoma include mutations in the PTCH gene and the p53 gene.[13] Mutations associated with melanoma include alterations in cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor-2A (CDKN2A), melanocortin-1 receptor (MC1R), BRAF, and DNA repair enzymes, such as UV-specific endonuclease in xeroderma pigmentosum.[14]

Multiple risk factors may synergistically interact with etiologic factors to accelerate skin cancer development, including age, sex, radiation exposure, environmental carcinogens, immune suppression, comorbid conditions, organ transplant history, family history, certain infections (eg, human papillomavirus), tanning bed use, vitamin levels, and occupational exposure.[15][16][17][4] Risk levels also vary within each category. For example, patients who receive thoracic cavity solid organ transplants (eg, heart) have a higher risk of skin cancer compared to those undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplants, renal transplants, or other solid organ transplants.[18]

Environmental carcinogens, such as arsenic and pollution, can accelerate DNA damage, increasing the risk of skin cancer.[19][20] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Overview of Environmental Skin Cancer Risks," for more information. Genetic predispositions also contribute to malignancies, as seen in conditions such as xeroderma pigmentosum, neurofibromatosis, and retinoblastoma.[21][22][23] Additionally, some skin cancers, such as Merkel cell carcinoma, are associated with infection, including the Merkel cell polyomavirus, which generally indicates a better prognosis in affected patients.[24] Although UV radiation is a significant factor in skin cancer development and progression, various other risk factors can accelerate this process on a case-by-case basis.

| Pause and Reflect |

What risk factors do many individuals regularly face in their day-to-day lives that may predispose them to skin cancer? How might you counsel individuals to reduce their exposure to environmental risk factors related to skin cancer? Why is it essential to know how many hours workers spend outside during their workday regarding their risk for skin cancer development? |

Epidemiology

Skin cancers are more frequent than any other type of cancer worldwide and in the United States.[25][26][1] The economic burden of risk factors, such as indoor tanning, contributes to the rising incidence of skin cancer, resulting in an annual economic burden of at least 8.1 billion dollars in the United States.[27][28] The increasing number of people diagnosed with skin cancer highlights a significant health challenge, both in terms of patient well-being and healthcare expenditures.[29]

Skin cancer occurs in all races worldwide but is more common in individuals with lighter skin, likely due to the reduced photoprotective effects of epidermal melanin.[30] In individuals with lighter skin, approximately 75% to 80% of nonmelanoma skin cancers are basal cell carcinomas, whereas up to 25% are squamous cell carcinomas.[31][32] Heritable defects in DNA repair mechanisms, such as those seen in xeroderma pigmentosum and Muir-Torre syndrome, also increase the risk of cutaneous carcinomas in some patients.

Among skin cancers, melanoma has the highest disability-adjusted life year, basal cell carcinoma has the highest incidence rate, and squamous cell carcinoma has the highest prevalence.[1] The incidence of melanoma in the United States, from 1990 to 2019, increased to 17 per 100,000 individuals, and prevalence increased to 138 per 100,000 individuals. Meanwhile, nonmelanoma skin cancer had an incidence of 787 per 100,000 individuals and a prevalence of 359 per 100,000 individuals.[1] Males had a higher incidence, prevalence, and mortality rate than females from 1990 to 2019.[1] Although skin cancer occurs in all age groups, it is more common in older adults, likely due to increased cumulative UV light exposure.[33][34] Geographically, melanoma rates are higher in the northern half of the United States compared to the southern half, while nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence is highest in the southeastern, western, and northeastern regions of the country.[1]

Other malignancies, such as Merkel cell carcinoma or Kaposi sarcoma, have unique epidemiological information outside the scope of this resource. Merkel cell carcinoma is far more common in men and among individuals with lighter skin.[35] Kaposi sarcoma is more common in individuals with HIV.[36] Worldwide, skin cancer rates are highest in populations with significant UV light exposure and lighter skin tones, such as those in Europe and Australia.[37][38]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of skin cancer is not fully understood, but various etiological factors, with UV light being the most prominent, interact with risk factors that likely contribute to the development and neoplastic proliferation of skin cancer.[39] These proliferations may be benign or malignant; benign proliferation typically results from dysregulation, while malignant proliferation is driven by genetic and molecular alterations associated with UV radiation.[39]

Exposure to UV light from solar radiation is the most significant modifiable risk factor for developing both nonmelanoma skin cancer and melanoma.[40] UV radiation can be categorized into UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C based on their respective wavelengths—approximately 320 to 380 nm for UV-A, 280 to 320 nm for UV-B, and 100 to 280 nm for UV-C.[37] Sunlight is primarily composed of UV-A (~90%) and UV-B (~10%) radiation,[7] while UV-C rays are absorbed mainly by the atmosphere.[41]

UV-A, with its longer wavelength, penetrates the dermis and generates free radicals.[42] UV-B, with a shorter wavelength, penetrates to the level of the stratum basale of the epidermis, leading to the formation of pyrimidine dimers, such as thymidine dimers.[43][44] Both UV-A and UV-B contribute to carcinogenesis, with UV-A significantly impacting skin aging.[45] UV radiation causes cell injury and apoptosis and impairs DNA repair mechanisms, leading to DNA mutations.[46][47] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Biochemistry, DNA Repair," for more information on DNA damage from UV radiation.

The development of cutaneous malignancy following DNA damage from solar radiation is multifactorial and influenced by genetic factors, Fitzpatrick skin type, and immunosuppressed status. Most (90%) cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas exhibit UV-induced p53 gene mutations, leading to uninhibited keratinocyte proliferation.[48] DNA mutations associated with basal cell carcinoma include mutations in the PTCH and p53 genes.[49] Melanoma-related DNA mutations include alterations in CDKN2A, MCR1, BRAF, and DNA repair enzymes, such as UV-specific endonuclease in xeroderma pigmentosum.[50][51] The complete list of genetic mutations and risk factors remains incomplete, but ongoing research continues to uncover new genes and targets involved in each subtype of skin cancer.[52][53][54]

Histopathology

The staging of skin cancer varies depending on the subtype and is beyond the scope of this resource. For example, histologic features of basal cell carcinoma include basophilic cells with minimal cytoplasm, and palisading or nests of cells may be observed. Necrosis and mitotic figures may also be evident (see Image. Basal Cell Carcinoma on Cheek—H&E Staining Showing Basaloid Islands). Histopathology showing intercellular bridges and pleomorphic nuclei, with or without nuclear molding, is consistent with squamous cell carcinoma. Keratin pearls may also be present but are not always observed (see Image. Squamous Cell Carcinoma). Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Dermatopathology, Cutaneous Lymphomas" and "Melanoma Pathology," for more information on skin cancer histopathology.

History and Physical

A thorough skin examination is essential for identifying premalignant and malignant skin lesions, during which key symptoms (such as itching, bleeding, pain, and irritation) should be explored. Notably, it is essential to assess the location, texture, size, color, shape, borders, and any recent changes in suspicious lesions. Premalignant actinic keratoses often present as rough, gritty skin papules on an erythematous base.[55] Basal cell carcinomas usually appear as pink, pearly papules with telangiectasia (see Image. Basal Cell Carcinoma Presenting as Pink Papules on a Patient's Skin).[56] Squamous cell carcinomas are often pink, rough papules, patches, and plaques (see Image. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma).[57]

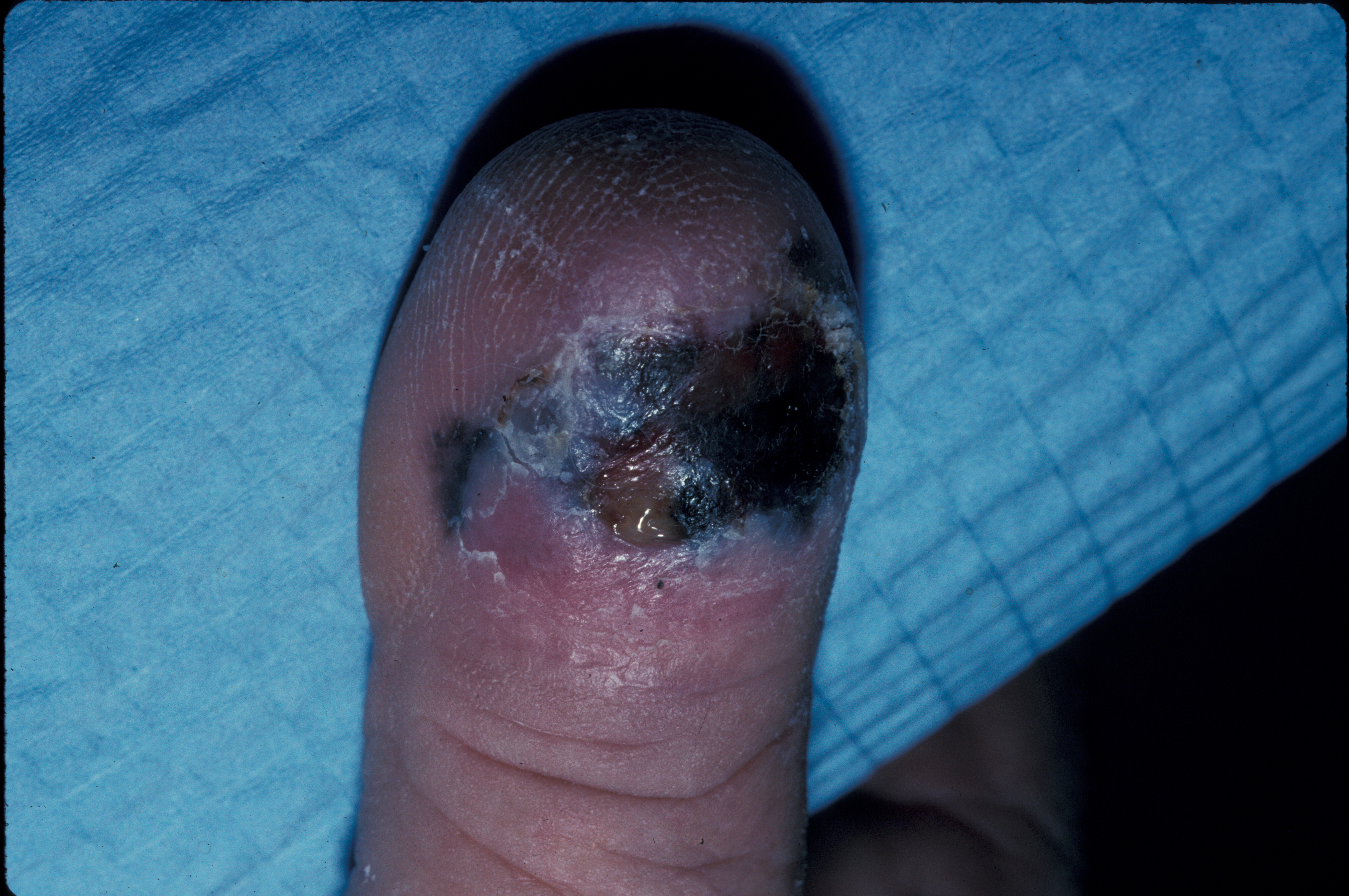

Melanomas are usually brown-to-black lesions with asymmetry, irregular borders, color variegation, and diameters greater than 6 mm (see Image. Ulcerated Acral Lentiginous Melanoma on Dorsal Toe). Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Dermatoscopic Characteristics of Melanoma Versus Benign Lesions and Nonmelanoma Cancers," for more information. Any new or changing lesion that differs from other body nevi (often referred to as the "ugly duckling sign") should be considered suspicious.[58] A thorough full-body examination should be performed as soon as possible when a patient presents with a suspicious lesion, such as one consistent with melanoma.

Basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas are commonly found on parts of the head and neck that accumulate the most UV radiation over a lifetime, such as the nose, ears, and upper lip. Melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, with the most frequent locations being the backs and shoulders of men and the lower limbs of women.[59] Studies comparing melanoma risk per unit skin area have shown that the face is the highest-risk area for melanoma.[60] However, the presentation of skin cancer can vary across different body types and skin colors, so a thorough examination with dermoscopy and further diagnostic workup may be necessary if the clinical history and examination are insufficient or equivocal.

Evaluation

Patients at risk for cutaneous malignancy are typically evaluated by a medical professional with a full-body skin examination. While most primary care providers can conduct this exam, specialists with advanced dermatology training may assist with dermoscopy, allowing for a more detailed inspection of suspicious lesions. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Dermatoscopic Characteristics of Melanoma Versus Benign Lesions and Nonmelanoma Cancers" and "Dermoscopy Overview and Extradiagnostic Applications," for more information on skin cancer evaluation with dermoscopy.

Most concerning lesions identified during a physical examination will undergo an office procedure called a skin biopsy, typically a shave or punch biopsy. This is performed under local anesthesia during an outpatient visit. The specimen is then sent to a trained dermatopathologist for interpretation. If the pathologist confirms a diagnosis of cutaneous malignancy, further intervention is typically required based on the pathological diagnosis and clinical context. In some cases, laboratory tests may be necessary to prognosticate or assess the extent of the disease. For example, patients with suspected Kaposi sarcoma should undergo an HIV test.

A shave or punch biopsy is typically sufficient for most nonmelanoma skin cancers, provided it reaches an adequate depth to analyze the tissue pattern and possible perineural invasion. For melanoma, however, complete excisional removal is recommended. In the case of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, a deep incisional biopsy is necessary. For many lymphomas, such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, a broad-shave biopsy is preferred over a punch biopsy. Meanwhile, for cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, a deep incisional biopsy is preferred.[5] Imaging may be required to assess bony invasion, such as with squamous cell carcinoma. Following specific tumor guidelines is important, such as those provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), as these are frequently updated to reflect the latest research.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of precancerous lesions and cutaneous malignancies should be individualized to achieve the best clinical outcome for each patient. When presented as isolated lesions, precancerous actinic keratoses can be treated with lesion-directed therapies, such as cryotherapy.[61] In cases where patients have numerous lesions or diffuse actinic damage, field-directed therapies may be more appropriate than treating each lesion individually.[61] These therapies can include topical agents, such as 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and ingenol mebutate, or photodynamic therapy, which involves sensitizing the skin with a topical agent before treatment.[62](B3)

Initial preemptive efforts should aim to reduce the patient's risk of developing cutaneous malignancies. This includes optimizing immunosuppressant regimens in solid organ transplant patients, such as switching to sirolimus, establishing appropriate surveillance schedules for patients receiving immunomodulatory therapies, and adequately treating precancerous lesions.[63]

Many superficial basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas can be treated with topical or local therapies, depending on provider preference. However, the standard approach is surgical treatment using destructive methods such as electrodesiccation and curettage or surgical excision. Larger cancers or those in functionally or cosmetically sensitive areas (eg, head and neck) may qualify for micrographic dermatologic surgery or other forms of peripheral and deep margin assessment, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, according to the Appropriate Use Criteria.[64][65][66] (B3)

Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Mohs Micrographic Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC) Guidelines," "Mohs Micrographic Surgery," "Mohs Micrographic Surgery Evaluation and Treatment of Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma," "Mohs Micrographic Surgery of Uncommon Tumors (Angiosarcoma, Eccrine, Paget, and Merkel Cell)," "Mohs Micrographic Surgery Management of Melanoma and Melanoma In Situ," and "Mohs Micrographic Surgery Evaluation and Treatment of Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans," for more information.

Patients with aggressive or recurrent basal cell carcinoma who are not good surgical candidates may be treated with radiation therapy, systemic medications (eg, vismodegib), or novel therapies such as oncolytic viruses.[67][68][69][70][71] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Vismodegib," for more information. Other malignancies, such as melanoma, are typically treated with surgical excision or other unique systemic therapies. Late-stage unresponsive malignancies may require chemotherapy or immunotherapy.[72][73](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Skin neoplasms can be either benign or malignant, with each type of skin cancer presenting in a variety of ways. Due to this diversity, the differential diagnosis includes all lesions that may appear as macules, patches, papules, plaques, or nodules. In rare cases, they may also present as vesicles, bullae, or pustules. The differential diagnoses should consider relevant vascular, infectious, neoplastic (eg, metastases to the skin from other organs), inflammatory, traumatic, metabolic, mechanical, allergic, autoimmune, and iatrogenic lesions.

Common lesions to distinguish from true skin cancer include:

- Psoriasis

- Atopic dermatitis

- Tinea corporis (or other body area)

- Acne vulgaris

- Warts

- Lupus erythematosus

- Actinic keratosis

- Metastatic skin tumors

- Sebaceous hyperplasia

- Nevus

- Benign melanocytic lesions

- Dysplastic nevi [74][75][76][77][78]

Cysts should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of skin cancer. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Dermatopathology Evaluation of Cysts," for more information.

Staging

The staging of skin cancer is specific to each subtype of skin cancer and is beyond the scope of this resource. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Clinical Guidelines for the Staging, Diagnosis, and Management of Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma," for more information on the staging, diagnosis, and management of cutaneous malignant melanoma.

Prognosis

Most skin cancers, particularly nonmelanoma types such as basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas, have a good prognosis with curative management.[79][80][81] However, prognosis can vary widely depending on the subtype. For example, Merkel cell carcinoma has an unfavorable prognosis, with survival rates often less than 20%.[82][83][84] The prognosis generally depends on specific risk factors and treatment options for each malignancy. Detailed prognosis for each subtype is beyond the scope of this resource.

Complications

Skin cancer can lead to several complications, many of which can be prevented with early detection and management. However, the complications vary based on the subtype of skin cancer. General complications include:

- Further invasion of the cancer locally, either peripherally or deeply, causing tissue damage and symptoms such as pain.[85]

- Metastasis of skin cancer to other areas of the body, including the brain, lungs, lymph nodes, or skin.[86]

- Infection of skin cancer, particularly in ulcerated lesions.[87]

- Scarring and tissue destruction from the cancer or its surrounding skin, which could lead to temporary or permanent physical debility or disfigurement.[88]

- Unpleasant patient-reported symptoms, such as pain, itching, bleeding, or discomfort in the area of the skin cancer.[89][90]

- Recurrence of skin cancer, even after treatment.[91]

- Psychiatric conditions associated with skin cancer, such as depression or anxiety.[92]

- Psychological complications, such as distress or fear.[93]

- Effects of treatments, such as adverse drug events.[94]

- Impaired immune function.[95]

Early evaluation and management of skin cancer are crucial to prevent potential complications. For example, recurrence rates of skin cancer vary widely depending on the subtype. Basal cell carcinoma has a rare recurrence rate after treatment with micrographic dermatologic surgery.[96] In contrast, mucinous carcinoma of the skin, which can be either primary or metastatic from other areas (eg, colon and breast), has a local recurrence rate estimated to be between 20% and 40%. Recurrence is most commonly associated with the tumor's size.[97] The interprofessional team's coordination throughout a patient's care continuum is essential in communicating skin cancer prevention, early detection of skin cancer, tailored treatment, and early detection of complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with skin cancer are at high risk for morbidity and mortality associated with the disease. Early identification and management are critical in reducing these risks. The care of skin cancer patients requires a collaborative approach among healthcare professionals to ensure patient-centered care and optimize outcomes. Dermatologists, primary care physicians, pathologists, surgeons, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers involved in patient care should have the necessary clinical skills and knowledge to accurately diagnose and manage skin cancer. This includes expertise in recognizing the varied clinical presentations and understanding the nuances of diagnostic techniques such as biopsies and histopathology.

Healthcare teams can improve early detection and, in some cases, the eradication of skin cancer through collaboration. Patient and caregiver education on risk factors, medication adherence, treatments, and prevention (eg, sun protection) is crucial to reduce morbidity associated with skin cancer.[98] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Skin Cancer Prevention," for more information on skin cancer prevention. A strategic approach is essential, incorporating evidence-based strategies to optimize treatment plans and minimize adverse effects. Ethical considerations should guide decision-making, ensuring informed consent and respecting patient autonomy in treatment choices.

Each healthcare professional must understand their responsibilities and contribute their unique expertise to the patient's care plan, fostering a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach. Effective interprofessional communication is crucial, facilitating seamless information exchange and collaborative decision-making among healthcare team members. Care coordination is pivotal in ensuring that the patient's journey from diagnosis to treatment and follow-up is well-managed, minimizing errors and enhancing patient safety. By embracing these principles—skill, strategy, ethics, responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and care coordination—healthcare professionals can deliver patient-centered care, ultimately improving patient outcomes and enhancing team performance in the management of skin cancer.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Basal Cell Carcinoma Presenting as Pink Papules on a Patient's Skin.

Kelly Nelson, MD, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Aggarwal P, Knabel P, Fleischer AB Jr. United States burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer from 1990 to 2019. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021 Aug:85(2):388-395. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.109. Epub 2021 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 33852922]

Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, Coldiron BM. Incidence Estimate of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer (Keratinocyte Carcinomas) in the U.S. Population, 2012. JAMA dermatology. 2015 Oct:151(10):1081-6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1187. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25928283]

Glazer AM, Winkelmann RR, Farberg AS, Rigel DS. Analysis of Trends in US Melanoma Incidence and Mortality. JAMA dermatology. 2017 Feb 1:153(2):225-226. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4512. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28002545]

Haddad S, Weise JJ, Wagenpfeil S, Vogt T, Reichrath J. Malignant Melanoma: Vitamin D Status as a Risk and Prognostic Factor - Meta-analyses and Systematic Review. Anticancer research. 2025 Jan:45(1):27-37. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.17390. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39740829]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceElston DM, Stratman EJ, Miller SJ. Skin biopsy: Biopsy issues in specific diseases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016 Jan:74(1):1-16; quiz 17-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.033. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26702794]

Kaplan B, von Dannecker R, Arbiser JL. The Carcinogenesis of the Human Scalp: An Immunometabolic-Centered View. International journal of molecular sciences. 2024 Nov 10:25(22):. doi: 10.3390/ijms252212064. Epub 2024 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 39596133]

D'Orazio J, Jarrett S, Amaro-Ortiz A, Scott T. UV radiation and the skin. International journal of molecular sciences. 2013 Jun 7:14(6):12222-48. doi: 10.3390/ijms140612222. Epub 2013 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 23749111]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArmstrong BK, Kricker A. How much melanoma is caused by sun exposure? Melanoma research. 1993 Dec:3(6):395-401 [PubMed PMID: 8161879]

Matsuda K, Kurohama H, Kuwatsuka Y, Iwanaga A, Murota H, Nakashima M. Detection of genome instability by 53BP1 expression as a long-lasting health effect in human epidermis surrounding radiation-induced skin cancers. Journal of radiation research. 2024 Dec 16:65(Supplement_1):i57-i66. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrae035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39679893]

Dousset L, Mahfouf W, Younes H, Fatrouni H, Faucheux C, Muzotte E, Khalife F, Rossignol R, Moisan F, Cario M, Claverol S, Favot-Laforge L, Nieminen AI, Vainio S, Ali N, Rezvani HR. Energy metabolism rewiring following acute UVB irradiation is largely dependent on nuclear DNA damage. Free radical biology & medicine. 2025 Feb 1:227():459-471. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.12.030. Epub 2024 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 39667588]

Li Y, Wang X, Liu X, Li X, Zhang J, Li Y. The dysregulation of PARP9 expression is linked to apoptosis and DNA damage in gastric cancer cells. PloS one. 2024:19(12):e0316476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0316476. Epub 2024 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 39739965]

Jasmine F, Argos M, Khamkevych Y, Islam T, Rakibuz-Zaman M, Shahriar M, Shea CR, Ahsan H, Kibriya MG. Molecular Profiling and the Interaction of Somatic Mutations with Transcriptomic Profiles in Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer (NMSC) in a Population Exposed to Arsenic. Cells. 2024 Jun 18:13(12):. doi: 10.3390/cells13121056. Epub 2024 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 38920684]

Murgia G, Valtellini L, Denaro N, Nazzaro G, Bortoluzzi P, Benzecry V, Passoni E, Marzano AV. Gorlin Syndrome-Associated Basal Cell Carcinomas Treated with Vismodegib or Sonidegib: A Retrospective Study. Cancers. 2024 Jun 7:16(12):. doi: 10.3390/cancers16122166. Epub 2024 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 38927872]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLópez Riquelme I, Martínez García S, Serrano Ordónez A, Martínez Pilar L. Germline mutations predisposing to melanoma and associated malignancies and syndromes: a narrative review. International journal of dermatology. 2024 Dec 9:():. doi: 10.1111/ijd.17602. Epub 2024 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 39651613]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWu S, Han J, Laden F, Qureshi AA. Long-term ultraviolet flux, other potential risk factors, and skin cancer risk: a cohort study. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2014 Jun:23(6):1080-9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0821. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24876226]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSaladi RN, Persaud AN. The causes of skin cancer: a comprehensive review. Drugs of today (Barcelona, Spain : 1998). 2005 Jan:41(1):37-53 [PubMed PMID: 15753968]

Long Y, Pan Y, Yang H, Wang X, Jiang Z, Sun T. The Genetic Causal Effect of Autoimmune Diseases on pan-Cancers: Evidence from Mendelian Randomization. Journal of Cancer. 2025:16(2):567-576. doi: 10.7150/jca.103693. Epub 2025 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 39744497]

Wheless L, Anand N, Hanlon A, Chren MM. Differences in Skin Cancer Rates by Transplanted Organ Type and Patient Age After Organ Transplant in White Patients. JAMA dermatology. 2022 Nov 1:158(11):1287-1292. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3878. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36169974]

Zhang Q, Man J, Zhao T, Sun D, Zhang Z. YTHDF2 promotes arsenic-induced malignant phenotypes by degrading PIDD1 mRNA in human keratinocytes. Chemico-biological interactions. 2025 Jan 25:406():111352. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2024.111352. Epub 2024 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 39675544]

MacRae JD, Abbott MD, Fufaa GD. Cancer incidence associations with drinking water arsenic levels and disinfection methods in Maine, USA. Journal of water and health. 2024 Nov:22(11):2246-2256. doi: 10.2166/wh.2024.313. Epub 2024 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 39611682]

Anh Luong TL, Hoang TL, Tran DP, Le TM, Tran H, Ho PT, Hoang HN, Giang H, Vu DL, Dinh NH, Nguyen MT, Nguyen HS. Identification of novel variants of XPA and POLH/XPV genes in xeroderma pigmentosum patients in Vietnam. Personalized medicine. 2024:21(6):341-351. doi: 10.1080/17410541.2024.2393073. Epub 2024 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 39655645]

Moodley M, Ortman C. Neurofibromatosis type 2-related schwannomatosis - An update. Seminars in pediatric neurology. 2024 Dec:52():101171. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2024.101171. Epub 2024 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 39622611]

Constantinou SM, Bennett DC. Cell Senescence and the Genetics of Melanoma Development. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 2024 Oct:63(10):e23273. doi: 10.1002/gcc.23273. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39422311]

Gamissans M, Muntaner-Virgili C, Penín RM, Marcoval J. Characteristics of Spontaneous Regression in Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Analysis of Patient and Tumor Features. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2024 Dec 14:():. pii: llae508. doi: 10.1093/ced/llae508. Epub 2024 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 39673745]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGordon R. Skin cancer: an overview of epidemiology and risk factors. Seminars in oncology nursing. 2013 Aug:29(3):160-9. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2013.06.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23958214]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, Watson M, Massetti GM, Richardson LC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections - United States, 1982-2030. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2015 Jun 5:64(21):591-6 [PubMed PMID: 26042651]

Guy GP Jr, Zhang Y, Ekwueme DU, Rim SH, Watson M. The potential impact of reducing indoor tanning on melanoma prevention and treatment costs in the United States: An economic analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2017 Feb:76(2):226-233. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.029. Epub 2016 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 27939556]

Kao SZ, Ekwueme DU, Holman DM, Rim SH, Thomas CC, Saraiya M. Economic burden of skin cancer treatment in the USA: an analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Data, 2012-2018. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2023 Mar:34(3):205-212. doi: 10.1007/s10552-022-01644-0. Epub 2022 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 36449145]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002-2006 and 2007-2011. American journal of preventive medicine. 2015 Feb:48(2):183-187. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036. Epub 2014 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 25442229]

Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatology nursing. 2009 Jul-Aug:21(4):170-7, 206; quiz 178 [PubMed PMID: 19691228]

Thamm JR, Schuh S, Welzel J. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Actinic Keratosis. What is New for The Management for Sun-Damaged Skin. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2024 Sep 1:14(3 S1):. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1403S1a146S. Epub 2024 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 39133637]

Aristizabal MA, Zieman D, Berman HS, Williams KA, Markham DJ, Heckman MG, Hochwald A, Barbosa NS, Degesys C. Disparities in Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Comparative Analysis of Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Individuals. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology. 2024 Oct:17(10):24-27 [PubMed PMID: 39445326]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDuan R, Jiang L, Wang T, Li Z, Yu X, Gao Y, Jia R, Fan X, Su W. Aging-induced immune microenvironment remodeling fosters melanoma in male mice via γδ17-Neutrophil-CD8 axis. Nature communications. 2024 Dec 30:15(1):10860. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-55164-3. Epub 2024 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 39738047]

Holdam ASK, Koudahl V, Frostberg E, Rønlund K, Rahr HB. Prevalence, incidence and trends of keratinocyte carcinoma in Denmark 2007-2021: A population-based register study. Cancer epidemiology. 2025 Feb:94():102732. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2024.102732. Epub 2024 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 39708578]

Terrell M, Dongarwar D, Rashid R, Hamisu S, Orengo I. Inpatient prevalence and factors associated with Merkel Cell Carcinoma inpatient hospitalization in the United States. Archives of dermatological research. 2024 Jul 27:316(8):489. doi: 10.1007/s00403-024-03222-7. Epub 2024 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 39066821]

Ruffieux Y, Mwansa-Kambafwile J, Metekoua C, Tombe-Nyahuma T, Bohlius J, Muchengeti M, Egger M, Rohner E. HIV-1 Viremia and Cancer Risk in 2.8 Million People: the South African HIV Cancer Match Study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2024 Dec 30:():. pii: ciae652. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciae652. Epub 2024 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 39736138]

Sharma K, Dixon KM, Münch G, Chang D, Zhou X. Ultraviolet and infrared radiation in Australia: assessing the benefits, risks, and optimal exposure guidelines. Frontiers in public health. 2024:12():1505904. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1505904. Epub 2024 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 39744344]

Indini A, Didoné F, Massi D, Puig S, Casadevall JR, Bennett D, Katalinic A, Sanvisens A, Ferrari A, Lasalvia P, Demuru E, Ragusa R, Mayer-da-Silva A, Blum M, Mousavi M, Kuehni C, Mihor A, Mandalà M, Trama A, EUROCARE-6 Working Group. Incidence and prognosis of cutaneous melanoma in European adolescents and young adults (AYAs): EUROCARE-6 retrospective cohort results. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2024 Dec:213():115079. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2024.115079. Epub 2024 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 39546860]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDidona D, Paolino G, Bottoni U, Cantisani C. Non Melanoma Skin Cancer Pathogenesis Overview. Biomedicines. 2018 Jan 2:6(1):. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6010006. Epub 2018 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 29301290]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVile GF, Tanew-Ilitschew A, Tyrrell RM. Activation of NF-kappa B in human skin fibroblasts by the oxidative stress generated by UVA radiation. Photochemistry and photobiology. 1995 Sep:62(3):463-8 [PubMed PMID: 8570706]

Beltrán FJ, Chávez AM, Jiménez-López MA, Álvarez PM. Kinetic modelling of UV(C) and UV(C)/H(2)O(2) oxidation of an aqueous mixture of antibiotics in a completely mixed batch photoreactor. Environmental science and pollution research international. 2024 Sep:31(43):55222-55238. doi: 10.1007/s11356-024-34812-7. Epub 2024 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 39225925]

Mohania D, Chandel S, Kumar P, Verma V, Digvijay K, Tripathi D, Choudhury K, Mitten SK, Shah D. Ultraviolet Radiations: Skin Defense-Damage Mechanism. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2017:996():71-87. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-56017-5_7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29124692]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMori M, Kobayashi H, Sugiyama C, Katsumura Y, Furihata C. Effect of aging on unscheduled DNA synthesis induction by UV-B irradiation in hairless mouse epidermis. The Journal of toxicological sciences. 2000 Aug:25(3):181-8 [PubMed PMID: 10987125]

Schmidt-Rose T, Pollet D, Will K, Bergemann J, Wittern KP. Analysis of UV-B-induced DNA damage and its repair in heat-shocked skin cells. Journal of photochemistry and photobiology. B, Biology. 1999 Nov-Dec:53(1-3):144-52 [PubMed PMID: 10672538]

Fotopoulou A, Angelopoulou MT, Pratsinis H, Mavrogonatou E, Kletsas D. A subset of human dermal fibroblasts overexpressing Cockayne syndrome group B protein resist UVB radiation-mediated premature senescence. Aging cell. 2024 Dec 19:():e14422. doi: 10.1111/acel.14422. Epub 2024 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 39698891]

Yan L, Cao X, Wang L, Chen J, Sancar A, Zhong D. Dynamics and mechanism of DNA repair by a bifunctional cryptochrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2024 Dec 10:121(50):e2417633121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2417633121. Epub 2024 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 39621923]

Ghosh S, Orman MA. UV-Induced DNA Repair Mechanisms and Their Effects on Mutagenesis and Culturability in Escherichia coli. bioRxiv : the preprint server for biology. 2024 Nov 14:():. pii: 2024.11.14.623584. doi: 10.1101/2024.11.14.623584. Epub 2024 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 39605428]

Black AP, Ogg GS. The role of p53 in the immunobiology of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2003 Jun:132(3):379-84 [PubMed PMID: 12780682]

Kim MY, Park HJ, Baek SC, Byun DG, Houh D. Mutations of the p53 and PTCH gene in basal cell carcinomas: UV mutation signature and strand bias. Journal of dermatological science. 2002 May:29(1):1-9 [PubMed PMID: 12007715]

Ascierto PA, Kirkwood JM, Grob JJ, Simeone E, Grimaldi AM, Maio M, Palmieri G, Testori A, Marincola FM, Mozzillo N. The role of BRAF V600 mutation in melanoma. Journal of translational medicine. 2012 Jul 9:10():85. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-85. Epub 2012 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 22554099]

Helgadottir H, Olsson H, Tucker MA, Yang XR, Höiom V, Goldstein AM. Phenocopies in melanoma-prone families with germ-line CDKN2A mutations. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2018 Sep:20(9):1087-1090. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.216. Epub 2017 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 29215650]

Gabriel JA, Weerasinghe N, Balachandran P, Salih R, Orchard GE. A Narrative Review of Molecular, Immunohistochemical and In-Situ Techniques in Dermatopathology. British journal of biomedical science. 2024:81():13437. doi: 10.3389/bjbs.2024.13437. Epub 2024 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 39741925]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMakwana K, Velazquez EJ, Marzese DM, Smith B, Bhowmick NA, Faries MB, Hamid O, Boiko AD. NRF-1 transcription factor regulates expression of an innate immunity checkpoint, CD47, during melanomagenesis. Frontiers in immunology. 2024:15():1495032. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1495032. Epub 2024 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 39742254]

Lagacé F, Mahmood F, Conte S, Mija LA, Moustaqim-Barrette A, LeBeau J, McKenna A, Maazi M, Hanna J, Kelly ASV, Lazarowitz R, Rahme E, Hrubeniuk TJ, Sweeney E, Litvinov IV. Investigating Skin Cancer Risk and Sun Safety Practices Among LGBTQ+ Communities in Canada. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont.). 2024 Dec 19:31(12):8039-8053. doi: 10.3390/curroncol31120593. Epub 2024 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 39727716]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLam J, Ellis SR, Sivamani RK. Inflamed actinic keratoses associated with pemetrexed and carboplatin therapy. Dermatology online journal. 2017 Oct 15:23(10):. pii: 13030/qt77s2r0p9. Epub 2017 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 29469794]

Stafford HD, Dokic Y, Huttenbach Y, Wasko C, Ranario JS. Report of Basal Cell Carcinoma Occurring With a Desmoplastic Trichilemmoma Successfully Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery. Cureus. 2024 Jun:16(6):e61910. doi: 10.7759/cureus.61910. Epub 2024 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 38975532]

Teoh J, Gan A, Ramalingam J, Elsheikh S, Jerrom R. Papular lesion occurring within a longstanding warty plaque, in skin of colour Fitzpatrick type 4-5. Skin health and disease. 2024 Apr:4(2):e328. doi: 10.1002/ski2.328. Epub 2024 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 38577042]

Daniel Jensen J, Elewski BE. The ABCDEF Rule: Combining the "ABCDE Rule" and the "Ugly Duckling Sign" in an Effort to Improve Patient Self-Screening Examinations. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology. 2015 Feb:8(2):15 [PubMed PMID: 25741397]

Ward WH, Farma JM, Matthews NH, Li WQ, Qureshi AA, Weinstock MA, Cho E. Epidemiology of Melanoma. Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy. 2017 Dec 21:(): [PubMed PMID: 29461782]

Green A, MacLennan R, Youl P, Martin N. Site distribution of cutaneous melanoma in Queensland. International journal of cancer. 1993 Jan 21:53(2):232-6 [PubMed PMID: 8425760]

Peris K, Fargnoli MC. Conventional treatment of actinic keratosis: an overview. Current problems in dermatology. 2015:46():108-14. doi: 10.1159/000366546. Epub 2014 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 25561214]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChung AT, Taguibao JN, Siripunvarapon AH, Frez MLF. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas in Xeroderma Pigmentosum-Variant Type Treated with Imiquimod 5% Cream and Radiotherapy: A Case Report. Acta medica Philippina. 2024:58(17):100-105. doi: 10.47895/amp.v58i17.9208. Epub 2024 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 39431256]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJoo V, Abdelhamid K, Noto A, Latifyan S, Martina F, Daoudlarian D, De Micheli R, Pruijm M, Peters S, Hullin R, Gaide O, Pantaleo G, Obeid M. Primary prophylaxis with mTOR inhibitor enhances T cell effector function and prevents heart transplant rejection during talimogene laherparepvec therapy of squamous cell carcinoma. Nature communications. 2024 Apr 30:15(1):3664. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-47965-3. Epub 2024 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 38693123]

Sleiwah A, Wright TC, Chapman T, Dangoor A, Maggiani F, Clancy R. Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans in Children. Current treatment options in oncology. 2022 Jun:23(6):843-854. doi: 10.1007/s11864-022-00979-9. Epub 2022 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 35394606]

Gil-Lianes J, Marti-Marti I, Morgado-Carrasco D. Secondary Intention Healing After Mohs Micrographic Surgery: An Updated Review of Classic and Novel Applications, Benefits and Complications. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2025 Jan 2:():. pii: S0001-7310(24)01058-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2024.09.024. Epub 2025 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 39755147]

Żółkiewicz J, Banciu L, Sławińska M, Frumosu M, Tebeică T, Sobjanek M, Leventer M. The Application of Mohs Micrographic Surgery in the Treatment of Acral Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Report of Two Cases. Journal of clinical medicine. 2024 Nov 5:13(22):. doi: 10.3390/jcm13226643. Epub 2024 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 39597787]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrampton JE, Basset-Séguin N. Vismodegib: A Review in Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma. Drugs. 2018 Jul:78(11):1145-1156. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0948-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30030732]

Mbous YPV, Mohamed R, Sambamoorthi U, Bharmal M, Kamal KM, LeMasters T, Kolodney J, Kelley GA. Effectiveness and Safety of Treatments for Early-Stage Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized and Non-Randomized Studies. Cancer medicine. 2025 Jan:14(1):e70553. doi: 10.1002/cam4.70553. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39749718]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGamret AC, Roberts JE, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Brief Overview. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2024 Nov:38(4):264-267. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-1791563. Epub 2024 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 39697403]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYacoub I, Rayn K, Choi JI, Bakst R, Chhabra A, Qian JY, Johnstone P, Simone CB 2nd. The Role of Radiation, Immunotherapy, and Chemotherapy in the Management of Locally Advanced or Metastatic Cutaneous Malignancies. Cancers. 2024 Nov 22:16(23):. doi: 10.3390/cancers16233920. Epub 2024 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 39682109]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNassief G, Anaeme A, Moussa K, Chen D, Ansstas G. Where Are We Now with Oncolytic Viruses in Melanoma and Nonmelanoma Skin Malignancies? Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland). 2024 Jul 9:17(7):. doi: 10.3390/ph17070916. Epub 2024 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 39065766]

Lugowska I, Teterycz P, Rutkowski P. Immunotherapy of melanoma. Contemporary oncology (Poznan, Poland). 2018 Mar:22(1A):61-67. doi: 10.5114/wo.2018.73889. Epub 2018 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 29628796]

Pelosi E, Castelli G, Testa U. Braf-Mutant Melanomas: Biology and Therapy. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont.). 2024 Dec 3:31(12):7711-7737. doi: 10.3390/curroncol31120568. Epub 2024 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 39727691]

Aran BM, Duran J, Gru AA. A Case of Leukemia Cutis (Acute Myeloid Leukemia) With Epidermotropism. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2025 Feb 1:47(2):141-144. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000002917. Epub 2024 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 39751635]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePawar PM, Mandli SJ, Solanki K, Sutaria AH. Pityriasis Lichenoides Chronica-Like Mycosis Fungoides: A Diagnostic Dilemma. Skinmed. 2024:22(6):482-484 [PubMed PMID: 39748587]

Bazzacco G, Zalaudek I, Errichetti E. Dermoscopy to differentiate clinically similar inflammatory and neoplastic skin lesions. Italian journal of dermatology and venereology. 2024 Apr:159(2):135-145. doi: 10.23736/S2784-8671.24.07825-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38650495]

Choudhary S, Srivastava A, Sahni M, Joshi D. Atypical Morphology of a Typical Mycobacterial Infection. Skinmed. 2023:21(6):439-440 [PubMed PMID: 38051246]

Luppi JB, Pereira de Souza R, Florezi GP, Nico MMS, Lourenço SV. The Role of Reflectance Confocal Microscopy in the Evaluation of Pigmented Oral Lesions and Their Relationship With Histopathological Aspects. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2022 Sep 1:44(9):658-663. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000002220. Epub 2022 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 35503878]

Smolle J, Wolf P. Is favorable prognosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin due to efficient immune surveillance? Archives of dermatology. 1997 May:133(5):645-6 [PubMed PMID: 9158419]

Pei M, Wiefels M, Harris D, Velez Torres JM, Gomez-Fernandez C, Tang JC, Hernandez Aya L, Samuels SE, Sargi Z, Weed D, Dinh C, Kaye ER. Perineural Invasion in Head and Neck Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers. 2024 Nov 1:16(21):. doi: 10.3390/cancers16213695. Epub 2024 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 39518134]

Catalano M, Nozzoli F, De Logu F, Nassini R, Roviello G. Management Approaches for High-Risk Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma with Perineural Invasion: An Updated Review. Current treatment options in oncology. 2024 Sep:25(9):1184-1192. doi: 10.1007/s11864-024-01234-z. Epub 2024 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 39102167]

D'Angelo SP, Bhatia S, Brohl AS, Hamid O, Mehnert JM, Terheyden P, Shih KC, Brownell I, Lebbé C, Lewis KD, Linette GP, Milella M, Georges S, Shah P, Ellers-Lenz B, Bajars M, Güzel G, Nghiem PT. Avelumab in patients with previously treated metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: long-term data and biomarker analyses from the single-arm phase 2 JAVELIN Merkel 200 trial. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer. 2020 May:8(1):. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000674. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32414862]

Schadendorf D, Lebbé C, Zur Hausen A, Avril MF, Hariharan S, Bharmal M, Becker JC. Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, prognosis, therapy and unmet medical needs. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2017 Jan:71():53-69. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.022. Epub 2016 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 27984768]

Lebbe C, Becker JC, Grob JJ, Malvehy J, Del Marmol V, Pehamberger H, Peris K, Saiag P, Middleton MR, Bastholt L, Testori A, Stratigos A, Garbe C, European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel Cell Carcinoma. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2015 Nov:51(16):2396-403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.131. Epub 2015 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 26257075]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHali F, Bousmara R, Mellouki A, Kerouach A, Marnissi F, Diouri M, Chiheb S. Comparative study of cutaneous malignant melanoma according to anatomical site: plantar versus non-plantar melanoma. Archives of dermatological research. 2024 Nov 20:317(1):35. doi: 10.1007/s00403-024-03523-x. Epub 2024 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 39565418]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHauschild A, Garbe C, Ascierto PA, Demidov L, Dreno B, Dummer R, Eggermont A, Forsea AM, Gebhardt C, Gershenwald JE, Hamid O, Hoeller C, Kandolf L, Kaufmann R, Kirkwood JM, Lebbé C, Long GV, Malvehy J, Martin-Algarra S, McArthur G, Neyns B, Richtig E, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Scolyer R, Sondak VK, Wainstein A, Weichenthal M, Nuti P, Melanoma World Society Study Group. Neoadjuvant or perioperative therapy for melanoma metastasis in clinical practice: an international survey. The Lancet. Oncology. 2025 Jan:26(1):12-14. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00627-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39756440]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcKenzie NC, Hickey MD, De la Sancha C, Coates SJ, Leslie KS. Ulcerative erythematous papules and plaques on the face and lower legs of a man living with HIV: a clinicopathological challenge. International journal of dermatology. 2024 Nov:63(11):1522-1524. doi: 10.1111/ijd.17362. Epub 2024 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 38965065]

Ung CY, Warwick A, Onoufriadis A, Barker JN, Parsons M, McGrath JA, Shaw TJ, Dand N. Comorbidities of Keloid and Hypertrophic Scars Among Participants in UK Biobank. JAMA dermatology. 2023 Feb 1:159(2):172-181. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.5607. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36598763]

Chen A, Dusza S, Bromberg J, Goldfarb S, Sanford R, Markova A. Quality of Life in Patients with Malignant Wounds Treated at a Wound Care Clinic. Research square. 2024 Sep 2:():. pii: rs.3.rs-4797536. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4797536/v1. Epub 2024 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 39281876]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNiculescu AG, Georgescu M, Marinas IC, Ustundag CB, Bertesteanu G, Pinteală M, Maier SS, Al-Matarneh CM, Angheloiu M, Chifiriuc MC. Therapeutic Management of Malignant Wounds: An Update. Current treatment options in oncology. 2024 Jan:25(1):97-126. doi: 10.1007/s11864-023-01172-2. Epub 2024 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 38224423]

Landov H, Baum S, Mansour R, Liberman B, Barzilai A, Alcalay J. Comparison of Surgical Treatment Using Mohs Micrographic Surgery versus Wide Local Excision for the Treatment of Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans. The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ. 2024 Dec:26(11):682-687 [PubMed PMID: 39692386]

Müller A, Dolbeault S, Piperno-Neumann S, Clerc M, Jarry P, Cassoux N, Lumbroso-Le Rouic L, Matet A, Rodrigues M, Holzner B, Malaise D, Brédart A. Anxiety, depression and fear of cancer recurrence in uveal melanoma survivors and ophthalmologist/oncologist communication during survivorship in France - protocol of a prospective observational mixed-method study. BMC psychiatry. 2024 Nov 15:24(1):812. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-06265-2. Epub 2024 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 39548476]

Thompson JR, Gomes L, Kouvelis G, Smith AL, Lo SN, Kasparian NA, Saw RPM, Dieng M, Seaman L, Martin LK, Guitera P, Milne D, Schmid H, Cust AE, Bartula I. Short-Term Effectiveness of a Stepped-Care Model to Address Fear of Cancer Recurrence in Patients With Early-Stage Melanoma. Psycho-oncology. 2024 Dec:33(12):e70041. doi: 10.1002/pon.70041. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39681994]

Liu R, Chen Y, Wu SN, Ma W, Qiu Z, Wang J, Xu X, Chen C, Wang W. Adverse drug events associated with capecitabine: a real-world pharmacovigilance study based on the FAERS database. Therapeutic advances in drug safety. 2024:15():20420986241303428. doi: 10.1177/20420986241303428. Epub 2024 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 39713991]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStasiak K, Stevens AD, Bolte AC, Curley CT, Perusina Lanfranca M, Lindsay RS, Eyo UB, Lukens JR, Price RJ, Bullock TNJ, Engelhard VH. Differential T cell accumulation within intracranial and subcutaneous melanomas is associated with differences in intratumoral myeloid cells. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2024 Nov 2:74(1):10. doi: 10.1007/s00262-024-03832-0. Epub 2024 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 39487854]

Clements S, Jeha GM, Tripuraneni P, Kelley B, Greenway H Jr. Recurrence Rates of Mohs Micrographic Surgery vs Radiation Therapy for Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Ear. Cutis. 2024 May:113(5):216-217. doi: 10.12788/cutis.1004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39042118]

Adefusika JA, Pimentel JD, Chavan RN, Brewer JD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: the Mayo Clinic experience over the past 2 decades. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2015 Feb:41(2):201-8. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000198. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25627628]

Li W, Hao N, Liu W, An D, Yan B, Li J, Liu L, Luo R, Zhang H, Lei D, Zhou D. The experience of the multidisciplinary team in epilepsy management from a resource-limited country. Epilepsia open. 2019 Mar:4(1):85-91. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12290. Epub 2018 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 30868118]