Introduction

Down syndrome was first described by an English physician, John Langdon Down, in 1866, but its association with chromosome 21 was established almost 100 years later by Dr. Jerome Lejeune in Paris. It is the presence of all or part of the third copy of chromosome 21 that causes Down syndrome, the most common chromosomal abnormality occurring in humans.[1] It is also found that the most frequently occurring live-born aneuploidy is trisomy 21, which causes this syndrome.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The majority of patients with Down syndrome have an extra copy of chromosome 21. There are different hypotheses related to the genetic basis of Down syndrome and the association of different genotypes with the phenotypes. Among them is gene dosage imbalance, in which there is an increased dosage or number of genes of Hsa21, which results in increased gene expansion.[3]. It further includes the possibility of association of different genes with different phenotypes of Down syndrome. The other popular hypothesis is the amplified development instability hypothesis, according to which the genetic imbalance created by a number of trisomic genes results in a greater impact on the expression and regulation of many genes.[3]

The critical region hypothesis is also well-known in this list. Down syndrome critical regions (DSCR) are a few chromosomal regions that are associated with partial trisomy for Has21. DSCR on 21q21.22 is responsible for many clinical features of Down syndrome.[3][4] After a thorough study of different analyses, it became clear that a single critical region gene cannot cause all the phenotypical features associated with trisomy 21, rather it is more evident that multiple critical regions or critical genes have a role to play in this phenomenon.[5]

Epidemiology

The incidence of Down syndrome increases with maternal age, and its occurrence varies in different populations (1 in 319 to 1 in 1000 live births)[6][7]. It is also known that the frequency of Down syndrome fetuses is quite high at the time of conception, but about 50% to 75% of these fetuses are lost before term. The occurrence of other autosomal trisomy is much more common than the 21, but the postnatal survival is very poor as compared to Down syndrome. This high percentage of survival of patients with trisomy 21 is thought to be a function of a small number of genes on chromosome 21 called Hsa21, which is the smallest and least dense of the autosomes.[8]

Pathophysiology

An extra copy of chromosome 21 is associated with Down syndrome, which occurs due to the failure of chromosome 21 to separate during gametogenesis, resulting in an extra chromosome in all the body cells. Robertsonian translocation and isochromosome or ring chromosome are the other 2 possible causes of trisomy 21. Isochromosome is a condition when 2 long arms separate together instead of the long and short arms while in Robertsonian translocation. This occurs in 2% to 4% of the patients. The long arm of chromosome 21 is attached to another chromosome, mostly chromosome 14. In mosaicism, there are 2 different cell lines because of the error of division after fertilization.[6]

History and Physical

Clinical Features

Different clinical conditions are associated with Down syndrome as different systems are affected by it. These patients have a wide array of signs and symptoms like intellectual and developmental disabilities or neurological features, congenital heart defects, gastrointestinal (GI) abnormalities, characteristic facial features, and abnormalities.[9]

Congenital Cardiac Defects (CHD)

Congenital cardiac defects are by far the most common and leading cause associated with morbidity and mortality in patients with Down syndrome, especially in the first 2 years of life. Though different suggestions have been made about the geographical as well as seasonal variation in the occurrence of different types of congenital cardiac defects in trisomy 21, so far none of the results have been conclusive.[10]

The incidence of CHD in babies born with Down syndrome is up to 50%. The most common cardiac defect associated with Down syndrome is an atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), and this defect makes up to 40% of the congenital cardiac defects in Down syndrome.[6] It is said to be associated with the mutation of the non-Hsa21 CRELD1 gene[6][11] The second most common cardiac defect in Down syndrome is a ventricular septal defect (VSD), which is seen in about 32% of the patients with Down syndrome. Together with AVSD, these account for more than 50% of congenital cardiac defects in patients with Down syndrome.[6][11]

The other cardiac defects associated with trisomy 21 are secundum atrial defect (10%), tetralogy of Fallot (6%), and isolated PDA (4%), while about 30% of the patients have more than one cardiac defect. There is geographical variation in the prevalence of the cardiac defect in Down syndrome, with VSD being the most common in Asia and secundum type ASD in Latin America. The reason behind this difference in the prevalence of different types of CHD in different regions is still unclear, and many factors such as regional proximity have been found to contribute.[6]

Because of such a high prevalence of CHD in patients with Down syndrome, it has been recommended that all patients get an echocardiogram within the first few weeks of life.

Gastrointestinal (GI) Tract Abnormalities

Patients with trisomy 21 have many structural and functional disorders related to the GI tract. Structural defects can occur anywhere from the mouth to anus, and it has been found that certain defects like duodenal and small bowel atresia or stenosis, annular pancreas, imperforate anus, and Hirschsprung disease occur more commonly in these patients as compared to the general population.[1]

About 2% of patients with Down syndrome have Hirschsprung disease while 12% of patients with Hirschsprung disease have Down syndrome.[1][6] Hirschsprung disease is a form of functional lower intestinal obstruction in which the neural cells fail to migrate to the distal segment of the rectum resulting in an aganglionic segment which does not have normal peristalsis resulting in failure of normal defecation reflex causing a functional obstruction.[12] The infant usually presents with signs and symptoms related to intestinal obstruction. Duodenal atresia and imperforate anus usually present in the neonatal period.

Apart from the structural defects patients with Down syndrome, patients are also prone to many other GI disorders like gastroesophageal reflux (GERD), chronic constipation, intermittent diarrhea, and celiac disease. Since there is a strong association of celiac disease with Down syndrome being present in about 5% of these patients, it is recommended to do yearly screening of celiac disease. Once diagnosed, these patients will have to remain on a gluten-free diet for the rest of life.[13]

Hematologic Disorders

There are several hematological disorders associated with Down syndrome. The hematological abnormalities in a newborn with Down syndrome (HANDS) constitute neutrophilia, thrombocytopenia, and polycythemia, which are seen in 80%, 66% and 34% of Down syndrome babies respectively.[14][15][16] HANDS is usually mild and resolves within the first thr3e weeks of life.[14][15][16]

The other disorder that is quite specific to Down syndrome is a transient myeloproliferative disorder, which is defined as detection of blast cells in younger than 3 month old babies with Down syndrome. It is characterized by the clonal proliferation of megakaryocytes and is detected during the first week of life and is resolved by 3 months of life. It is also known as transient abnormal myelopoiesis or transient leukemia and is known to be present in about 10% of patients with Down syndrome. If this occurs in the fetus, it can cause spontaneous abortion.[17][18]

Patients with Down syndrome are 10-times more at risk of developing leukemia,[19] which constitute about 2% of all pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia and 10% of all pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Thirty percent of Down syndrome patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia have an association with function mutation in Janus Kinase 2 gene.[20]

About 10% of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (TML) develop leukemogenesis of acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) before the age of 4 years. AMKL is associated with GATA1 gene which is an X-linked transcriptor factor leading to an uncontrolled proliferation of immature megakaryocytes.[21]

Neurologic Disorders

Trisomy of Hsa21 has associated with reduced brain volume especially hippocampus and cerebellum.[22] Hypotonia is the hallmark of babies with Down syndrome and is present in almost all of them. It is defined as decreased resistance to passive muscle stretch and is responsible for delayed motor development in these patients.[23]. Because of hypotonia Down syndrome patients have joint laxity that causes decreased gait stability and increased energy requirement for physical exertion.[24]. These patients are prone to decreased bone mass and increased risk of fractures due to the low level of physical activity[25], while the ligamentous laxity predisposes these patients to atlantoaxial subluxation.[26]

Five percent to 13% of children with Down syndrome have seizures[27], out of that, 40% will have seizures before their first birthday, and in these cases, the seizures are usually infantile spasms.[28] Down syndrome children with infantile spasm do respond better to antiepileptics as compared to other kids with the same, and therefore, early intervention and treatment improve the developmental outcome.[27]

Lennox-Gestaut syndrome is also seen to be more prevalent in children with Down syndrome when it does occur, has a late onset, and is associated with reflex seizures along with an increased rate of EEG abnormalities.[29]

Forty percent of patients with Down syndrome develop tonic-clonic or myoclonic seizures in their first 3 decades.[28] Dementia occurs more commonly in patients older than 45 years of age with Down syndrome[30], and about 84% are more prone to develop seizures.[31] The seizures in these patients are related to the rapid decline in their cognitive functions.[32]

The risk of developing early-onset Alzheimer disease is significantly high in patients with Down syndrome with 50% to 70% of patients developing dementia by the age of 60 years.[33] Amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is known to be associated with increased risk for the Alzheimer disease is found to be encoded on Hsa21, and trisomy of this protein is likely to be responsible for increased frequency of dementia in people with Down syndrome. Recent studies have shown that triplication of APP is associated with increased risk of early-onset Alzheimer disease even in the normal population.[34]

Nearly all the patients with Down syndrome have mild to moderate learning disability. Trisomy of multiple genes including DYRK1A, synaptojanin 1, and single-minded homolog 2 (SIM2) have been found to cause learning and memory defects in mice, which suggests the possibility that the overexpression of these genes may likely be causing the learning disability in people with Down syndrome.[35]

Endocrinological Disorders

Thyroid gland dysfunction is most commonly associated with Down syndrome. Hypothyroidism can be congenital or acquired at any time during life.[25] The newborn screening program in New York has reported an increased incidence of congenital hypothyroidism in babies with Down syndrome as compared to the others.[36] The anti-thyroid autoantibodies were found in 13% to 34% of patients with Down syndrome who had acquired hypothyroidism, and the concentration of these antibodies increased after 8 years of life.[25]. About half of the patients with Down syndrome have been shown to have subclinical hypothyroidism with elevated TSH and normal thyroxine levels.[37] Hyperthyroidism is much less frequent in patients with Down syndrome as compared to hypothyroidism, although the rate of it still exceeds the incidence of hyperthyroidism in the general pediatric population.[38]

Abnormalities in sexual development are also noted to be significant with delayed puberty in both genders. In girls, primary hypogonadism presents as delay in menarche or adrenarche, while in boys it can manifest as cryptorchidism, ambiguous genitalia, micropenis, small testes, low sperm count, and scanty growth of axillary and pubic hair.[25]

The insulin-like growth factor is also said to be responsible for the delay in skeletal maturation and short stature in patients with Down syndrome.[25]

Musculoskeletal Disorders

Children with Down syndrome are at an increased risk of reduced muscle mass because of hypotonia increased ligamentous laxity which causes retardation of gross motor skills and can result in joint dislocation.[39] These patients also have vitamin D deficiency due to several factors like inadequate exposure to sunlight, inadequate intake of vitamin D, malabsorption secondary to celiac disease, increased breakdown because of anticonvulsant therapy, among other factors. These factors increase the risk of decreased bone mass in children with Down syndrome and predispose them to recurrent fractures.[40]

Refractive Errors and Visual Abnormalities

Ocular and orbital anomalies are common in children with Down syndrome. These include blepharitis (2-7%), keratoconus (5-8%), cataract (25% to 85%), retinal anomalies (0% to 38%), strabismus (23% to 44%), amblyopia (10% to 26%), nystagmus (5% to 30%), refractive errors (18% to 58%), glaucoma (less than 1%), iris anomalies (38% to 90%) and optic nerve anomalies (very few cases).

The ocular anomalies, if left untreated, can significantly affect the lives of these patients. Therefore, all the patients with Down syndrome should have an eye exam is done during the first 6 months of life and then annually.[41]

Otorhinolaryngological (ENT) Disorders

Ear, nose, and throat problems are also quite common in patients with Down syndrome. The anatomical structure of the ear in Down syndrome patients predisposes them to hearing deficits. Hearing loss is usually conductive because of impaction of cerumen and middle ear pathologies, including chronic middle ear effusion due to the small Eustachian tube, acute otitis media, and eardrum perforation. These patients usually require pressure equalization tubes for the treatment.

The sensorineural hearing loss has also been associated with Down syndrome because of the structural abnormalities in the inner ears such as narrow internal auditory canals.[42]

Evaluation

There are different methods used for the prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome. Ultrasound, between 14 and 24 weeks of gestation, can be used as a tool for diagnosis based on soft markers like increased nuchal fold thickness, small or no nasal bone, and large ventricles.[43] Nuchal translucency (NT) is detected by ultrasound and is caused by a collection of fluid under the skin behind the fetal neck. It is done between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation. Other causes of this finding include Other causes are trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome), trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome), and Turner syndrome. Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling have widely been used for the diagnosis, but there is a small risk of miscarriages between 0.5% to 1%.[44]

Several other methods have also been developed and are used for the rapid detection of trisomy 21 both during fetal life and after birth. The FISH of interphase nuclei is most commonly used by either using Hsa21-specific probes or the whole of the Hsa21.[45] Another method that is currently being used is QF-PCR, in which the presence of 3 different alleles is determined by using DNA polymorphic markers.[46] The success of this method depends upon the informative markers and the presence of DNA. It has been found that up to 86.67% of cases of Down syndrome can be identified by using the STR marker method.[47]

A relatively new method called paralogue sequence quantification (PSQ) uses the paralogue sequence on the Hsa21 copy number. It is a PCR-based method that uses the paralogue genes to detect the targeted chromosome number abnormalities, which is known as paralogue sequence quantification.[48]

There are non-invasive prenatal diagnostic methods that are being studied to be used for the diagnosis of Down syndrome prenatally. These are based on the presence of fetal cells in the maternal blood and the presence of cell-free fetal DNA in the maternal serum. [49]

Cell-free fetal DNA makes up 5% to 10% of the maternal plasma, and it increases during pregnancy and clears after delivery. Though this method has been used to determine fetal Rh status in Rhive women[50], sex in sex-linked disorders[51], and for the detection of paternally inherited autosomal recessive and dominant traits,[52] its use for the detection of chromosomal aneuploidy, especially the trisomy is still a challenge.

Few other recent methods like digital PCR and next-generation sequencing (NGS) are also being developed for the diagnosis of Down syndrome.[53]

Treatment / Management

The management of patients with Down syndrome is multidisciplinary. Newborns with suspicion of Down syndrome should have a karyotyping done to confirm the diagnosis. The family needs to be referred to the clinical geneticist for the genetic testing and counseling of both parents.

Parental education is one of the foremost aspects regarding the management of Down syndrome, as parents need to be aware of the different possible conditions associated with it so that they can be diagnosed and treated appropriately. Treatment is basically symptomatic, and complete recovery is not possible.

These patients should have their hearing and vision assessed, and as they are more prone to have cataracts, timely surgery is required. Thyroid function tests should be done on a yearly basis and, if deranged, should be managed accordingly.

A balanced diet, regular exercise, and physical therapy are needed for optimum growth and weight gain, although feeding problems improve after cardiac surgery.

Cardiac referral should arranged for all the patients regardless of the clinical signs of congenital heart disease. If present, this should be corrected within the first 6 months of life to ensure optimum growth and development of the child.

Other specialties involved include a developmental pediatrician, pediatric pulmonologist, gastroenterologist, neurologist, neurosurgeon, orthopedic specialist, child psychiatrist, physical and occupational therapist, speech and language therapist, and audiologist.

Differential Diagnosis

- Congenital hypothyroidism

- Mosaic trisomy 21 syndrome

- Partial trisomy 21(or 21q duplication)

- Robertsonian trisomy 21

- Trisomy 18

- Zellweger syndrome or other peroxisomal disorders

Prognosis

With the recent advances in the medical practice, development of surgical techniques for the correction of congenital disabilities, and improvement in general care, there has been a tremendous increase in the survival of infants and life expectancy of patients with Down syndrome. A Birmingham (United Kingdom) study done almost 60 years ago showed that 45% of infants survived the first year of life, and only 40% would be alive at 5 years.[54] A later study conducted about 50 years after that showed that 78% of patients with Down syndrome plus a congenital heart defect survived for 1 year, while the number went up to 96% in patients without the anomalies.[55] This rise in the life expectancy of these patients should continue to rise significantly because of the developments in medical science. Healthcare facilities aim to provide proper and timely management to these patients and to help them to have a fulfilled and productive life.[56]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of patients with Down syndrome is an interprofessional endeavor. Newborns with suspicion of Down syndrome should have a karyotyping done to confirm the diagnosis. The family needs to be referred to the clinical geneticist for the genetic testing and counseling of both parents.

Because almost every organ system is involved, the child needs to be seen by the ophthalmologist, orthopedic surgeon, cardiologist, dermatologist, gastroenterologist, physical therapist, mental health nurse, ENT surgeon, and behavior specialist.

Parental education is one of the foremost aspects regarding the management of Down syndrome, as parents need to be aware of the different possible conditions associated with it so that they can be diagnosed and treated appropriately. Treatment is basically symptomatic, and complete recovery is not possible.

While life span has increased over the past 3 decades, these individuals still have a shorter life expectancy compared to healthy individuals.

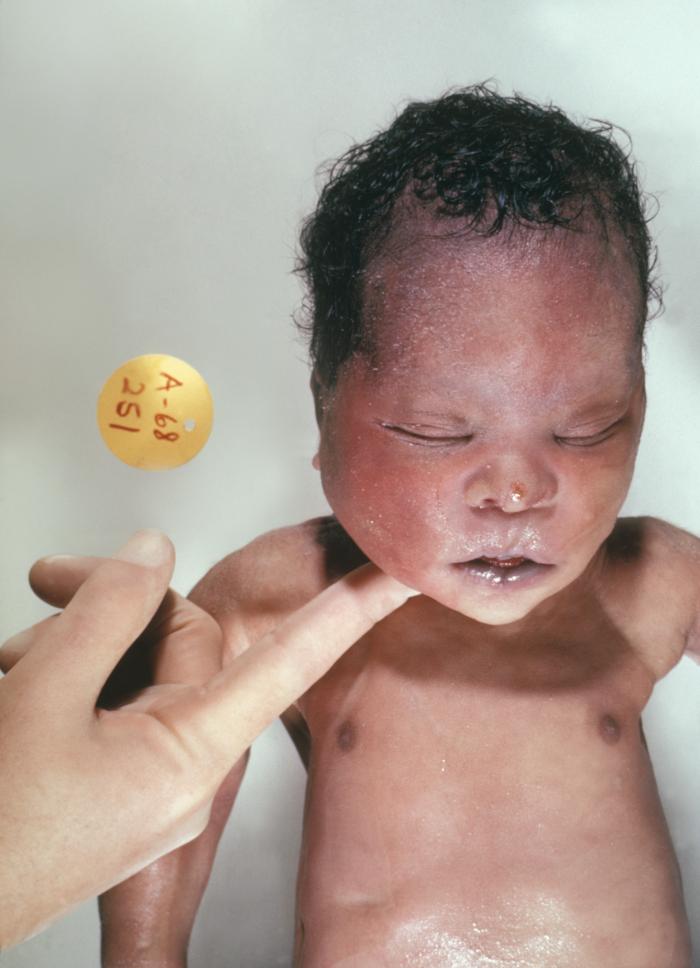

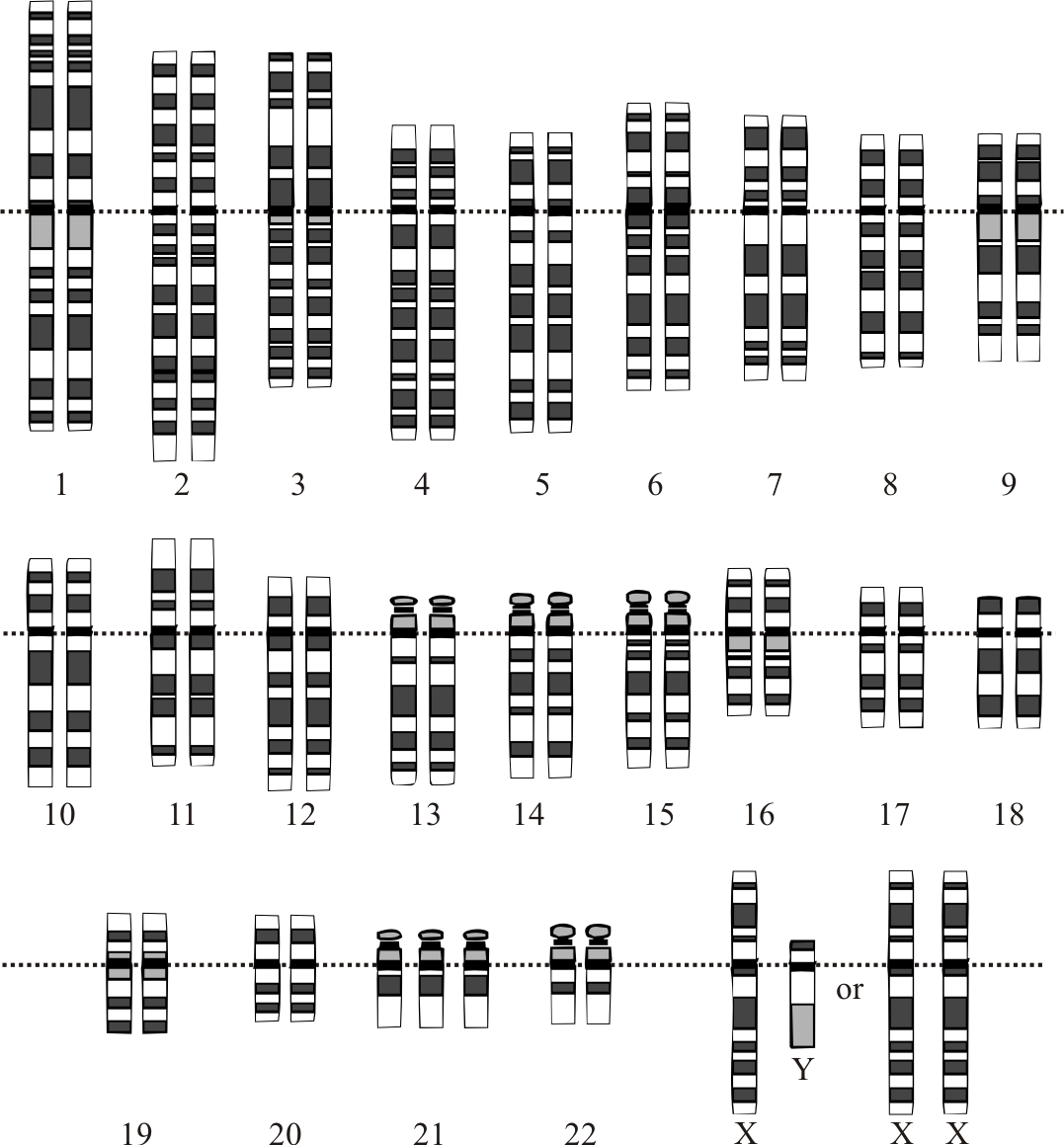

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Holmes G. Gastrointestinal disorders in Down syndrome. Gastroenterology and hepatology from bed to bench. 2014 Winter:7(1):6-8 [PubMed PMID: 25436092]

Gardiner K, Herault Y, Lott IT, Antonarakis SE, Reeves RH, Dierssen M. Down syndrome: from understanding the neurobiology to therapy. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010 Nov 10:30(45):14943-5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3728-10.2010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21068296]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAntonarakis SE, Lyle R, Dermitzakis ET, Reymond A, Deutsch S. Chromosome 21 and down syndrome: from genomics to pathophysiology. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2004 Oct:5(10):725-38 [PubMed PMID: 15510164]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePritchard MA, Kola I. The "gene dosage effect" hypothesis versus the "amplified developmental instability" hypothesis in Down syndrome. Journal of neural transmission. Supplementum. 1999:57():293-303 [PubMed PMID: 10666684]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHolland AJ, Hon J, Huppert FA, Stevens F. Incidence and course of dementia in people with Down's syndrome: findings from a population-based study. Journal of intellectual disability research : JIDR. 2000 Apr:44 ( Pt 2)():138-46 [PubMed PMID: 10898377]

Asim A, Kumar A, Muthuswamy S, Jain S, Agarwal S. "Down syndrome: an insight of the disease". Journal of biomedical science. 2015 Jun 11:22(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12929-015-0138-y. Epub 2015 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 26062604]

Bittles AH, Glasson EJ. Clinical, social, and ethical implications of changing life expectancy in Down syndrome. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2004 Apr:46(4):282-6 [PubMed PMID: 15077706]

Roper RJ, Reeves RH. Understanding the basis for Down syndrome phenotypes. PLoS genetics. 2006 Mar:2(3):e50 [PubMed PMID: 16596169]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChoi JK. Hematopoietic disorders in Down syndrome. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2008 Jan 1:1(5):387-95 [PubMed PMID: 18787621]

Benhaourech S, Drighil A, Hammiri AE. Congenital heart disease and Down syndrome: various aspects of a confirmed association. Cardiovascular journal of Africa. 2016 Sep/Oct:27(5):287-290. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2016-019. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27805241]

Wiseman FK, Alford KA, Tybulewicz VL, Fisher EM. Down syndrome--recent progress and future prospects. Human molecular genetics. 2009 Apr 15:18(R1):R75-83. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19297404]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmiel J, Sproat-Emison E, Garcia-Barcelo M, Lantieri F, Burzynski G, Borrego S, Pelet A, Arnold S, Miao X, Griseri P, Brooks AS, Antinolo G, de Pontual L, Clement-Ziza M, Munnich A, Kashuk C, West K, Wong KK, Lyonnet S, Chakravarti A, Tam PK, Ceccherini I, Hofstra RM, Fernandez R, Hirschsprung Disease Consortium. Hirschsprung disease, associated syndromes and genetics: a review. Journal of medical genetics. 2008 Jan:45(1):1-14 [PubMed PMID: 17965226]

Wallace RA. Clinical audit of gastrointestinal conditions occurring among adults with Down syndrome attending a specialist clinic. Journal of intellectual & developmental disability. 2007 Mar:32(1):45-50 [PubMed PMID: 17365367]

Henry E, Walker D, Wiedmeier SE, Christensen RD. Hematological abnormalities during the first week of life among neonates with Down syndrome: data from a multihospital healthcare system. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2007 Jan 1:143A(1):42-50 [PubMed PMID: 17163522]

Hord JD, Gay JC, Whitlock JA. Thrombocytopenia in neonates with trisomy 21. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 1995 Jul:149(7):824-5 [PubMed PMID: 7795778]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMiller M, Cosgriff JM. Hematological abnormalities in newborn infants with Down syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. 1983 Oct:16(2):173-7 [PubMed PMID: 6228141]

Zipursky A, Brown E, Christensen H, Sutherland R, Doyle J. Leukemia and/or myeloproliferative syndrome in neonates with Down syndrome. Seminars in perinatology. 1997 Feb:21(1):97-101 [PubMed PMID: 9190039]

Zipursky A, Brown EJ, Christensen H, Doyle J. Transient myeloproliferative disorder (transient leukemia) and hematologic manifestations of Down syndrome. Clinics in laboratory medicine. 1999 Mar:19(1):157-67, vii [PubMed PMID: 10403079]

Hasle H, Clemmensen IH, Mikkelsen M. Risks of leukaemia and solid tumours in individuals with Down's syndrome. Lancet (London, England). 2000 Jan 15:355(9199):165-9 [PubMed PMID: 10675114]

Kearney L, Gonzalez De Castro D, Yeung J, Procter J, Horsley SW, Eguchi-Ishimae M, Bateman CM, Anderson K, Chaplin T, Young BD, Harrison CJ, Kempski H, So CW, Ford AM, Greaves M. Specific JAK2 mutation (JAK2R683) and multiple gene deletions in Down syndrome acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2009 Jan 15:113(3):646-8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-170928. Epub 2008 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 18927438]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWechsler J, Greene M, McDevitt MA, Anastasi J, Karp JE, Le Beau MM, Crispino JD. Acquired mutations in GATA1 in the megakaryoblastic leukemia of Down syndrome. Nature genetics. 2002 Sep:32(1):148-52 [PubMed PMID: 12172547]

Pearlson GD, Breiter SN, Aylward EH, Warren AC, Grygorcewicz M, Frangou S, Barta PE, Pulsifer MB. MRI brain changes in subjects with Down syndrome with and without dementia. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 1998 May:40(5):326-34 [PubMed PMID: 9630260]

Lott IT. Neurological phenotypes for Down syndrome across the life span. Progress in brain research. 2012:197():101-21. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-54299-1.00006-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22541290]

Agiovlasitis S, McCubbin JA, Yun J, Pavol MJ, Widrick JJ. Economy and preferred speed of walking in adults with and without Down syndrome. Adapted physical activity quarterly : APAQ. 2009 Apr:26(2):118-30 [PubMed PMID: 19478345]

Hawli Y, Nasrallah M, El-Hajj Fuleihan G. Endocrine and musculoskeletal abnormalities in patients with Down syndrome. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2009 Jun:5(6):327-34. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.80. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19421241]

Merrick J, Ezra E, Josef B, Hendel D, Steinberg DM, Wientroub S. Musculoskeletal problems in Down Syndrome European Paediatric Orthopaedic Society Survey: the Israeli sample. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. Part B. 2000 Jun:9(3):185-92 [PubMed PMID: 10904905]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArya R, Kabra M, Gulati S. Epilepsy in children with Down syndrome. Epileptic disorders : international epilepsy journal with videotape. 2011 Mar:13(1):1-7. doi: 10.1684/epd.2011.0415. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21398208]

Pueschel SM, Louis S, McKnight P. Seizure disorders in Down syndrome. Archives of neurology. 1991 Mar:48(3):318-20 [PubMed PMID: 1825777]

Ferlazzo E, Adjien CK, Guerrini R, Calarese T, Crespel A, Elia M, Striano P, Gelisse P, Bramanti P, di Bella P, Genton P. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome with late-onset and prominent reflex seizures in trisomy 21 patients. Epilepsia. 2009 Jun:50(6):1587-95. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01944.x. Epub 2009 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 19187280]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMenéndez M. Down syndrome, Alzheimer's disease and seizures. Brain & development. 2005 Jun:27(4):246-52 [PubMed PMID: 15862185]

De Simone R, Puig XS, Gélisse P, Crespel A, Genton P. Senile myoclonic epilepsy: delineation of a common condition associated with Alzheimer's disease in Down syndrome. Seizure. 2010 Sep:19(7):383-9. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.04.008. Epub 2010 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 20598585]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLott IT, Doran E, Nguyen VQ, Tournay A, Movsesyan N, Gillen DL. Down syndrome and dementia: seizures and cognitive decline. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2012:29(1):177-85. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111613. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22214782]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJanicki MP, Dalton AJ. Prevalence of dementia and impact on intellectual disability services. Mental retardation. 2000 Jun:38(3):276-88 [PubMed PMID: 10900935]

Hunter CL, Bachman D, Granholm AC. Minocycline prevents cholinergic loss in a mouse model of Down's syndrome. Annals of neurology. 2004 Nov:56(5):675-88 [PubMed PMID: 15468085]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVoronov SV, Frere SG, Giovedi S, Pollina EA, Borel C, Zhang H, Schmidt C, Akeson EC, Wenk MR, Cimasoni L, Arancio O, Davisson MT, Antonarakis SE, Gardiner K, De Camilli P, Di Paolo G. Synaptojanin 1-linked phosphoinositide dyshomeostasis and cognitive deficits in mouse models of Down's syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008 Jul 8:105(27):9415-20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803756105. Epub 2008 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 18591654]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHaddow JE, Palomaki GE, Allan WC, Williams JR, Knight GJ, Gagnon J, O'Heir CE, Mitchell ML, Hermos RJ, Waisbren SE, Faix JD, Klein RZ. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Aug 19:341(8):549-55 [PubMed PMID: 10451459]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTüysüz B, Beker DB. Thyroid dysfunction in children with Down's syndrome. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2001 Dec:90(12):1389-93 [PubMed PMID: 11853334]

Lavard L, Ranløv I, Perrild H, Andersen O, Jacobsen BB. Incidence of juvenile thyrotoxicosis in Denmark, 1982-1988. A nationwide study. European journal of endocrinology. 1994 Jun:130(6):565-8 [PubMed PMID: 8205255]

Morris AF, Vaughan SE, Vaccaro P. Measurements of neuromuscular tone and strength in Down's syndrome children. Journal of mental deficiency research. 1982 Mar:26(Pt 1):41-6 [PubMed PMID: 6210779]

Cabana MD, Capone G, Fritz A, Berkovitz G. Nutritional rickets in a child with Down syndrome. Clinical pediatrics. 1997 Apr:36(4):235-7 [PubMed PMID: 9114996]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMerrick J, Koslowe K. Refractive errors and visual anomalies in Down syndrome. Down's syndrome, research and practice : the journal of the Sarah Duffen Centre. 2001 Jul:6(3):131-3 [PubMed PMID: 11501216]

Shott SR. Down syndrome: common otolaryngologic manifestations. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2006 Aug 15:142C(3):131-40 [PubMed PMID: 16838306]

Agathokleous M, Chaveeva P, Poon LC, Kosinski P, Nicolaides KH. Meta-analysis of second-trimester markers for trisomy 21. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013 Mar:41(3):247-61. doi: 10.1002/uog.12364. Epub 2013 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 23208748]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRenna MD, Pisani P, Conversano F, Perrone E, Casciaro E, Renzo GC, Paola MD, Perrone A, Casciaro S. Sonographic markers for early diagnosis of fetal malformations. World journal of radiology. 2013 Oct 28:5(10):356-71. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i10.356. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24179631]

Kuo WL, Tenjin H, Segraves R, Pinkel D, Golbus MS, Gray J. Detection of aneuploidy involving chromosomes 13, 18, or 21, by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to interphase and metaphase amniocytes. American journal of human genetics. 1991 Jul:49(1):112-9 [PubMed PMID: 2063863]

Jain S, Agarwal S, Panigrahi I, Tamhankar P, Phadke S. Diagnosis of Down syndrome and detection of origin of nondisjunction by short tandem repeat analysis. Genetic testing and molecular biomarkers. 2010 Aug:14(4):489-91. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2009.0191. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20722466]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJain S, Panigrahi I, Gupta R, Phadke SR, Agarwal S. Multiplex quantitative fluorescent polymerase chain reaction for detection of aneuploidies. Genetic testing and molecular biomarkers. 2012 Jun:16(6):624-7. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2011.0243. Epub 2012 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 22313045]

Deutsch S, Choudhury U, Merla G, Howald C, Sylvan A, Antonarakis SE. Detection of aneuploidies by paralogous sequence quantification. Journal of medical genetics. 2004 Dec:41(12):908-15 [PubMed PMID: 15591276]

Walknowska J, Conte FA, Grumbach MM. Practical and theoretical implications of fetal-maternal lymphocyte transfer. Lancet (London, England). 1969 Jun 7:1(7606):1119-22 [PubMed PMID: 4181601]

Daniels G, Finning K, Martin P, Massey E. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of fetal blood group phenotypes: current practice and future prospects. Prenatal diagnosis. 2009 Feb:29(2):101-7. doi: 10.1002/pd.2172. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19085963]

Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, Rai V, Sargent IL, Redman CW, Wainscoat JS. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet (London, England). 1997 Aug 16:350(9076):485-7 [PubMed PMID: 9274585]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWright CF, Burton H. The use of cell-free fetal nucleic acids in maternal blood for non-invasive prenatal diagnosis. Human reproduction update. 2009 Jan-Feb:15(1):139-51. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn047. Epub 2008 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 18945714]

Voelkerding KV, Dames SA, Durtschi JD. Next-generation sequencing: from basic research to diagnostics. Clinical chemistry. 2009 Apr:55(4):641-58. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112789. Epub 2009 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 19246620]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRECORD RG, SMITH A. Incidence, mortality, and dex distribution of mongoloid defectives. British journal of preventive & social medicine. 1955 Jan:9(1):10-5 [PubMed PMID: 14351707]

Bell R, Rankin J, Donaldson LJ, Northern Congenital Abnormality Survey Steering Group. Down's syndrome: occurrence and outcome in the north of England, 1985-99. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 2003 Jan:17(1):33-9 [PubMed PMID: 12562470]

Skotko BG, Davidson EJ, Weintraub GS. Contributions of a specialty clinic for children and adolescents with Down syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2013 Mar:161A(3):430-7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35795. Epub 2013 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 23401090]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence