Introduction

Male stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is the unintentional release of urine during activities characterized by an increase in intraabdominal pressure that significantly impacts life quality.[1] Symptoms of male SUI vary from sporadic leakage of small amounts of urine to complete loss of bladder control.[1] The most common causes of male SUI are radical prostatectomy and neurological disease.[1]

Approximately 5% to 10% of men 65 years and older experience some form of urinary incontinence, and as many as 60% of men experience some degree of urinary incontinence following prostatectomy.[2][3] The initial treatment of male SUI comprises lifestyle modifications, pelvic floor physical therapy, bladder retraining, and medications; surgical options such as urethral slings are considered only when conservative management proves ineffective.[1][4]

A male sling is a synthetic strip positioned beneath the anterior bulbous urethra to facilitate urethral coaptation and reduce or prevent leakage.[5] The modern male sling was introduced in the 1990s as a minimally invasive surgical alternative to artificial urinary sphincters (AUS).[6][7] The management of male SUI is a constantly evolving field, and several adjustable and nonadjustable slings are currently available for widespread use.[5]

This activity reviews the indications for and contraindications to male sling placement and the required equipment, personnel, and techniques to complete such a procedure. The activity also reviews the identification, evaluation, and management of the most frequent complications of male sling placement and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving outcomes for men with SUI.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Maintaining male urinary continence is complex, relying on voluntary and involuntary interactions between various lower urinary tract muscular and connective tissue components.[8] This intricate anatomical unit is collectively called the urethral sphincter complex, comprising the internal (IUS) and external (EUS) urethral sphincters.[8][9]

The IUS is positioned at the level of the bladder neck and comprises smooth muscle fibers that are continuous with the inner longitudinal layer of the detrusor muscle and encircle the proximal urethra and bladder neck.[8][10][11][12] Tonic activation of the internal sphincter via sympathetic innervation during bladder filling ensures passive urethral closure, serving as the initial point of urinary control before the external sphincter.[13][14] Sympathetic innervation originates from the inferior hypogastric plexus with nerve roots T10-L2.[15]

The EUS comprises incomplete circular striated muscle fibers enveloping the membranous urethra as it traverses the pelvic floor within the deep perineal pouch; the bulbar urethra is anterior, and the anorectal ring is posterior.[8][9][10][11][12][16] The EUS is anchored within the bony pelvis to the bilateral pubic rami, suspended anteriorly to the pubic symphysis by the puboprostatic ligaments, and posteriorly to the perineal membrane.[9][12][17]

The EUS ensures continence during activities that cause sudden elevations in intraabdominal pressure via rapid contraction.[8] The pudendal nerve and pelvic nerve plexus dually innervate the EUS.[18][19] Contraction of the levator ani elevates and compresses the proximal urethra against the pubic bone, creating a muscular sling around the external urethral sphincter, further constricting the urethral lumen.[9][12][16][18]

These two urinary sphincters are integrated functional units extending from the bladder neck to the urogenital diaphragm.[11] The EUS compresses the membranous urethra to prevent urine flow, and the IUS contracts the bladder neck.[9] During micturition, parasympathetic stimulation induces relaxation of the IUS and detrusor contraction, facilitating urine passage coordinated with the simultaneous opening of the EUS.[9][19][20]

Pathophysiology of Male Stress Urinary Incontinence

Disruption of the sphincter complex is frequently observed after prostate surgery and can lead to urinary incontinence.[21] Post-prostatectomy SUI is often ascribed to external sphincter or pudendal nerve injury; damage to any part of the urethral sphincter complex can contribute to SUI.[1][21] Careful dissection during radical prostatectomy is critical for preserving the continence mechanism, particularly the striated portion of the EUS, as division of the bladder neck affects the passive continence mechanism produced by the IUS.[22]

Radical prostatectomy additionally weakens the structural support to the urethra due to damage to the endopelvic fascia and puboprostatic ligaments.[23] Studies have indicated that patients exhibit decreased urethral closure pressures and shortened functional urethral lengths after prostate surgery compared to continent controls due to compromises of the outlet resistance provided by the EUS and pelvic floor muscles.[21]

Male SUI may also occur secondary to urethral sphincter dysfunction due to neurologic disease, congenital abnormalities, direct traumatic injury, or postoperative bladder neck dysfunction.[1] In these patients, one or more of the following mechanisms contribute to SUI: disruption of the proximal bladder neck sphincter complex, denervation of the EUS impairing normal function, or inadequate urethral resistance and closure due to a dysfunctional urethral sphincter complex.[1][10]

Indications

Decisions regarding the optimum treatment of male SUI are guided by a comprehensive evaluation comprising a complete medical history, thorough physical examination, urinalysis, documentation of the postvoid residual, pad testing, urodynamics, and cystoscopy.[24]

Male Urethral Slings

A male urethral sling is typically recommended for men with mild-to-moderate urine leakage, characterized as 0 to 2 pads per day or a total pad weight of less than 500 grams in 24 hours. Some experts have suggested a 24-hour urine pad weight of 150 grams or less as a cutoff indication for urethral sling placement.[25] A male urethral sling may also be appropriate for patients who have not responded adequately to conservative management.[5][26][27][28] Patients with severe incontinence are unlikely to achieve optimum results with male sling placement; an artificial sphincter may be a better option.

A male sling may also be indicated for men with post-prostatectomy SUI who exhibit some degree of residual voluntary sphincter function but have not responded sufficiently to conservative therapies; a history of pelvic radiotherapy is not an absolute contraindication to MS placement.[5][24][29] The residual sphincteric function can be evaluated endoscopically during awake cystoscopy or through urodynamic studies.[5] These patients must generate sufficient bladder pressure to surmount the urethral resistance the sling produces.[5]

Patients with isolated nocturnal urinary incontinence may benefit from a nighttime male external vacuum catheter. These catheters are appropriate for overnight use only and must be connected to a suction device.

Dual-Balloon Adjustable Continence Device Therapy

Dual-balloon adjustable continence device therapy (DBACT) employs percutaneously implanted bilateral periurethral silicon balloons to provide passive sphincter complex compression and control leakage.[30][31] The degree of compression can be adjusted by changing the balloon volume in the clinic or office via an accessible titanium scrotal port.[31] Placement, adjustment, and removal of the DBACT device can be accomplished in an office-based setting under local anesthesia. DBACT is indicated for men with moderate-to-severe SUI of at least 12 months duration due to intrinsic urethral deficiency after prostate surgery; severe SUI or a history of pelvic radiotherapy are relative contraindications to DBACT placement.[32][33]

Artificial Urinary Sphincter

An artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) is more appropriate for patients with significant, severe, and bothersome incontinence or a history of pelvic radiotherapy who have failed to respond sufficiently to less invasive treatments.[4][34][35][36][37] The main contraindication to AUS placement is an inability to operate the device due to limited manual dexterity or an inability to understand device operation.[26][38] AUS placement is the most invasive procedure for male SUI but may be the optimum intervention for complicated and severe incontinence. Detrusor instability, active urinary tract infection, bladder outlet obstruction, small bladder capacity, recurrent urethral strictures, and high post-void residual urine volumes are relative contraindications to AUS placement.[35][37]

Procedure Selection

Selecting the most appropriate male incontinence procedure requires consideration of the nature and severity of the incontinence, any history of radiotherapy, prior surgical procedures, comorbidities, reasonable patient expectations, and the functional status of the sphincter complex.[34][39] Patients with partial sphincteric function may be better candidates for a nonadjustable sling.[24][29] Patients without a history of pelvic radiotherapy with complete sphincteric loss who are not candidates for an AUS can be reasonably considered for DBACT or male sling placement.[40][41][42] Patients with a history of pelvic radiotherapy radiation history may benefit from an adjustable male sling.[43][44]

The overarching principle for device selection is multifactorial and must consider the experience of the surgeon, patient comorbidities, functional status, living situation, and the goal of the intervention. Patients may desire either the reduction of symptoms or the best chance of complete resolution.[4][5][34]

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications to sling procedures for male SUI include:

- The presence of bladder pathology with the possibility of renal compromise, such as a loss of compliance or vesicoureteral reflux at low intravesical pressures.

- Compromised bladder neck or urethral tissue integrity, particularly that requiring bladder neck closure or urinary diversion.

- Unresolved urinary outlet obstruction, such as an intractable, recurrent, or untreated urethral stricture.

- Untreated urinary tract infection.

Relative contraindications to sling procedures for male SUI include:

- History of prior pelvic radiation therapy or urethral erosions.[45]

- Patients with an increased likelihood of future transurethral procedures, including surveillance cystoscopy for urothelial carcinoma.

- Severe stress incontinence that an isolated sling procedure is unlikely to resolve completely.

- History of AUS placement: an AUS may be placed after a sling procedure.[46]

- Shortened life expectancy secondary to significant comorbidities such as metastatic malignancy.

Equipment

The equipment required to perform a male sling procedure for male SUI typically includes:

- Minor surgical tray

- Adson forceps

- Adson-Beckman and Richardson retractors

- Richardson retractors

- Metzenbaum, Mayo, and suture scissors

- Needle driver

- Surgical field antibiotic/antiseptic irrigation

- 3-0 and 4-0 braided and 4-0 monofilament absorbable sutures

- Skin tissue adhesive

- Electrocautery

- Perineal self-retractor

- 16F indwelling catheter

- Male urethral sling device

Personnel

The personnel required to perform an MS procedure for male SUI typically includes:

- Primary surgeon

- Surgical first assistant

- Anesthesia personnel

- Surgical technician or operating room nurse

- Circulating or operating room nurse

- Male urethral sling device company representative who can offer technical device guidance and troubleshooting

Preparation

Cystoscopy is a required component of the preoperative evaluation for all patients considering male sling placement. Additionally, a standing cough stress test or urodynamic evaluation is recommended.[39] The force of detrusor contraction must be high enough to overcome the intended partial outflow obstruction from the male sling and facilitate complete bladder emptying.[5] Preoperative urinalysis is essential to document the absence of urinary tract infection.[47]

Technique or Treatment

Male urethral sling procedures are performed in the dorsal lithotomy position with appropriate cushioning for pressure points.[48] Prophylactic antibiotics should be administered intravenously before the incision. Hair should be removed from the thighs and perineum with clippers before chlorhexidine, and betadine skin antisepsis is performed.[49] The surgical field should be draped in a sterile fashion to exclude the perianal area.[50] Place a 16F indwelling catheter to reduce the risk of intraoperative bladder perforation.[48]

A male sling may be placed via a transobtuator or retropubic approach; some devices require a combined approach.[5]

Transobturator Male Urethral Sling Technique

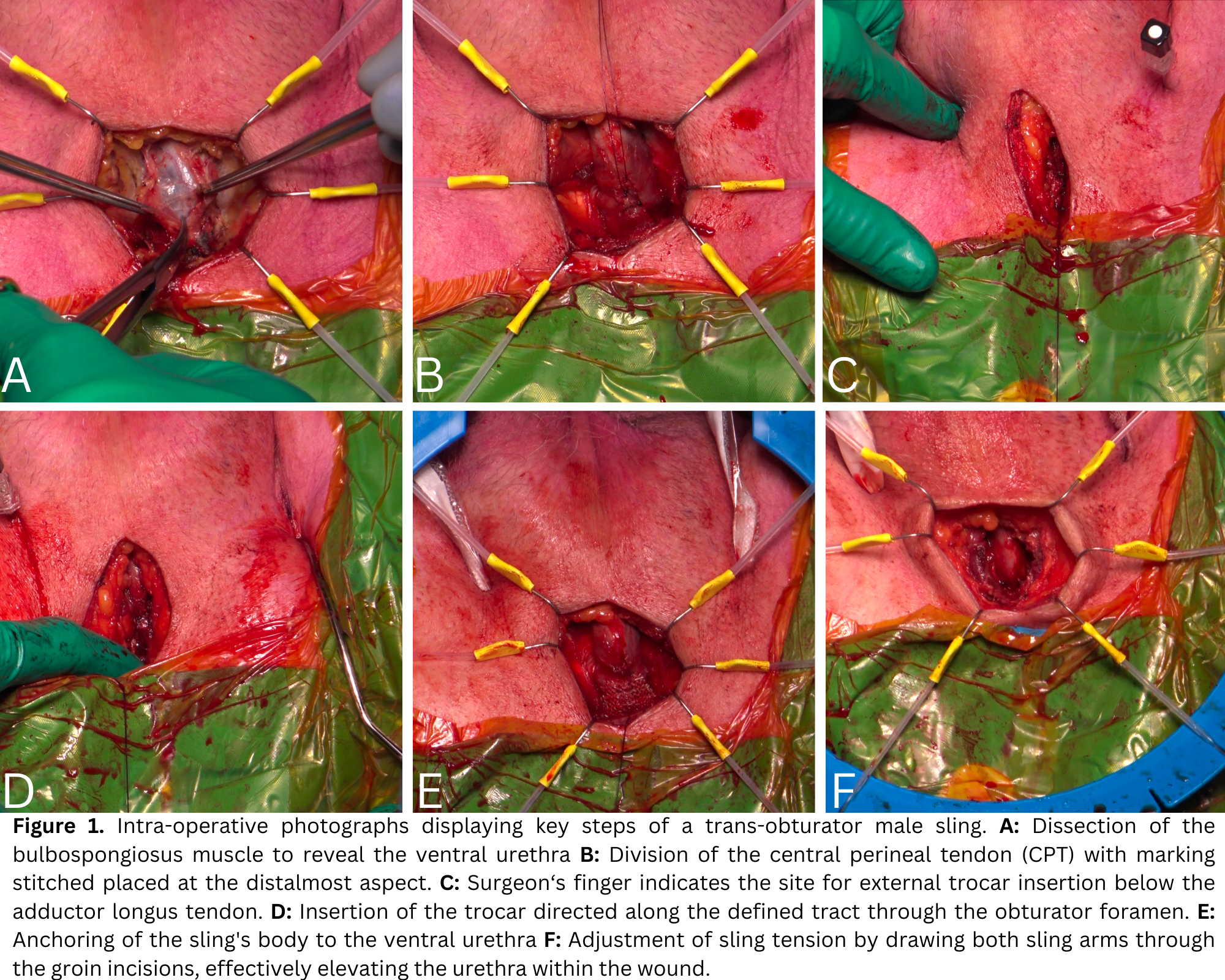

Create a 5-cm vertical midline perineal incision precisely centered over the mid-bulbar urethra. Sharply dissect the bulbospongiosus muscle to expose the ventral urethra. Divide the perineal body or central perineal tendon and mark its distal-most aspect; this is the most proximal location for sling placement.[48]

To determine the size of the internal trocar exit, use a finger to delineate the triangular area formed by the lateral aspect of the urethra, inferior pubic rami, and medial aspect of the corporeal bodies.[51] The site of external trocar insertion should be situated 1.5 to 2 cm inferior to the insertion point of the adductor longus tendon. Once this point is identified, make a vertical stab incision with the scalpel.[48]

Delineate the trocar tract through the obturator foramen by introducing a spinal needle into the groin incision angled toward the coccyx; manipulate the spinal needle through the obturator foramen. Insert the trocar with its handle parallel to the perineal incision directed toward the previously defined tract. Apply steady pressure until 2 distinct "pops" are heard or felt; this signifies the passage of the trocar through the endopelvic fascia.[48][51]

Laterally adjust the trocar handle position by 45° degrees while maintaining its trajectory to ensure the proper alignment.[48] Place a finger at the trocar exit site to facilitate trocar guidance and medially displace the urethra out of the trocar's path.[51] Rotate the trocar handle to direct the trocar through the exit site and bring its tip into view. Secure the lateral sling loop to the trocar and bring the sling through the tract by reversing the path of the trocar. Repeat these steps on the contralateral side.[48]

Anchor the body of the sling to the ventral urethra using a 4-0 braided absorbable suture, ensuring the proximal aspect of the sling is positioned distal to the insertion of the central perineal tendon.[48] Draw both sling arms through the groin incisions to elevate the urethra and determine the appropriate sling tension.[5][48][51] Divide the sling and its overlying plastic sheath and cut the sling flush with the skin at the groin incision.[48][51] Reapproximate the bulbospongiosus muscle to cover the urethra and the body of the sling using 4-0 braided absorbable sutures. See Image. Transobturator Male Sling Insertion.

Close the perineal incision with a running stitch using 3-0 braided absorbable sutures. Close all skin incisions with 4-0 monofilament sutures and apply skin tissue adhesive.[48]

Retropubic Male Urethral Sling Technique

The retropubic approach for male sling insertion employs a perineal and an abdominal incision.[5] The perineal incision resembles that used in the transobturator approach but preserves the bulbospongiosus muscle and the central perineal tendon, which remain intact.[5][50]

Create a transverse suprapubic abdominal incision to access the rectus fascia. Bilaterally, place trocars in a retropubic position to pierce the fascia and exit in the same fashion as the transobturator approach.[27] Thread the sling device via the tracts created by the trocars, providing tension to the body of the sling positioned overlying the ventral urethra.

Perform a cystoscopy before passing the sling to document the absence of any bladder or urethral perforations.[27] Anchor the sling according to the device-specific manufacturer instructions and close the incisions described above.

Variations in Technique

The techniques employed during male sling placement are frequently device-specific. Some transobturator sling devices allow for or require inside-to-outside sling insertion, and some require that the central perineal tendon remains intact. Other devices have 2 sling arms on each side, allowing for transobturator and retropubic, or sometimes prepubic, fixation.[27]

Postoperative Care

Patients undergoing male sling placement for male SUI may be discharged on the day of surgery or kept overnight for observation.[51] A voiding trial can be commenced on the first postoperative day. Patients who fail a voiding trial can be treated with indwelling catheter placement and undergo a repeat voiding trial in 7 days after further recovery and a reduction in postoperative edema.[48]

If patients fail the second voiding trial, trials may be performed weekly, or intermittent self-catheterization can be initiated by patients able to comply. Repeat voiding trials or self-catheterization should continue until spontaneous urethral voiding results in bladder emptying.[48] Urinary retention lasting more than 3 months should prompt consideration of sling lysis.[48]

Patients undergoing male sling placement require postoperative analgesia, stool softeners, and 5 days of antibiotic coverage.[48][51] To minimize the risk of sling loosening, patients must avoid lifting objects in excess of 10 pounds and strenuous activity for 6 weeks.[48] Strenuous activity includes but is not limited to squatting, bending, climbing, extreme leg spreads, biking, jogging, and sexual activity. Immersive bathing and swimming should be avoided for 2 weeks following the procedure.

Complications

The most common postoperative complications of male sling placement for male SUI include transient perineal pain, urinary retention, de novo urgency, and infection.[4][52] Up to 45% of patients report some degree of postoperative pelvic pain, although this is typically mild and self-limited.[53] Urinary retention rates range from 3% to 46%, depending on the type of sling used.[4][29] The risk of infection is low and estimated at 1% to 3%.[4]

Compared to the artificial urinary sphincter, male slings have a much lower reoperation rate of approximately 1%.[4][54] Device erosion occurs in less than 1% of cases and is primarily observed when slings are placed after pelvic radiotherapy.[4][52] Patients with a history of pelvic radiotherapy are at increased risk for postoperative infections, incomplete resolution of symptoms, and an ultimate need for device explant.[55]

Device slippage occurs in less than 1% of patients and is usually secondary to sling disruption due to activities resulting in increased intraabdominal pressure.[48] Device slippage or failure may be treated with readjustment of adjustable slings or may require salvage AUS, DBACT, or repeated sling placement.[48]

Intraoperative complications during MS placement are very rare and are typically characterized by bleeding from an obturator vessel, urethral injury, or bladder perforation from the trocar insertion. Bleeding from trocar sites during male sling placement is reported to be minimal and self-limited in most cases. One study of 115 patients undergoing MS placement of the same device reported intraoperative bleeding requiring transfusion in 0.9% of patients.[56]

The rate of urethral injury from trocar passage is very low; reported rates are between 0% and 1.8%.[29][56][57] This risk is minimized by employing best intraoperative practices, including bladder emptying before trocar passage. Bladder perforation or injury during trocar passage is similarly uncommon; studies of transobturator and retropubic approaches report rates between 0% and 1.6%.[29][57][58]

Clinical Significance

The overall success rates for male slings range from 36% to 90%; success is typically defined as requiring 0 to 1 pad per day or a reduction of more than 50% in leakage, although definitions can vary across studies.[52] Success is also contingent on the preoperative severity of the SUI, with success rates of 80% to 90% observed for mild incontinence, 32% to 83% for moderate incontinence, and rates up to 70% for severe incontinence.[40][52][54][59][60] Overall, male sling procedures result in either a cure or substantial improvement in SUI in approximately 75% of properly selected patients.

Patient satisfaction often exceeds objective success rates, with patients reporting improved quality of life despite residual leakage.[54] However, the durability of male slings diminishes over time, with efficacy declining after five years, which may necessitate revision, replacement, the insertion of a DBACT device, or the placement of an AUS.

Factors such as the severity of stress urinary incontinence, prior radiation therapy, and previous surgeries are associated with sling failure.[52] No substantial data currently suggests the superiority of adjustable slings over nonadjustable slings.[5] Patients must be counseled preoperatively regarding the outcomes of male sling placement, including decreasing efficacy and the possibility of not achieving complete continence.[5]

AUS is considered the gold standard for managing male SUI due to its superior efficacy and adaptability through an active, adjustable mechanism that allows cuff closure pressure to be tailored; AUS placement is associated with higher complication rates and increased complexity.[1] Long-term studies have indicated that up to 50% of patients achieve complete continence for up to 5 years following AUS placement, and an AUS is the recommended choice for patients with severe incontinence.[26][61][62] Placement of an AUS appears to offer a superior outcome compared to male sling placement in patients with a history of radiotherapy, although outcomes may depend on the specific male sling device.[63][64] However, operating an AUS requires manual dexterity from patients, and they carry a higher risk of erosions and infection. Additionally, patients with an AUS have a 20% to 30% rate of device revision or explantation.[1][61][65]

Shared decision-making should involve a comprehensive discussion regarding the benefits, risks, and outcomes of each device available to treat SUI, and the selection of a device should be tailored to the specific clinical situation and patient preferences.[1][5][65] However, current guidelines generally recommend slings as the first-line surgical treatment for mild-to-moderate male SUI, with treatment decisions guided by patient-specific factors.[26][34]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Providing effective counseling and education for patients considering male sling surgery necessitates an interprofessional team approach. Urologists and advanced practice providers must accurately convey the benefits, risks, limitations, and alternatives of the procedure during informed consent discussions with the patient and his family. This process facilitates shared decision-making and helps set appropriate expectations regarding postoperative urinary control.

Nurses play a pivotal role in preoperative education, guiding patients through the details of the procedure, recovery expectations, and postdischarge care. Their regular interactions with patients also allow for the reinforcement of critical information. Pharmacists ensure the proper management of perioperative medications and are responsible for the prudent use of antibiotics for surgical prophylaxis.

Effective communication and coordination among team members are vital for ensuring consistent patient education and seamless care transitions. Urologists, nurses, and other healthcare staff must collaborate to address patient queries and concerns. Following the placement of the sling, the team continues to engage with patients regarding recovery milestones, activity restrictions, follow-up care, and any potential complications that may require prompt treatment.

The interprofessional team enhances patient comprehension, safety, and overall satisfaction by working together. A collaborative approach to patient counseling ultimately fosters optimal outcomes and positive experiences for male sling surgery patients.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Koch GE, Kaufman MR. Male Stress Urinary Incontinence. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2022 Aug:49(3):403-418. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2022.04.005. Epub 2022 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 35931433]

Shamliyan TA, Wyman JF, Ping R, Wilt TJ, Kane RL. Male urinary incontinence: prevalence, risk factors, and preventive interventions. Reviews in urology. 2009 Summer:11(3):145-65 [PubMed PMID: 19918340]

Ko KJ, Kim SJ, Cho ST. Sling Surgery for Male Urinary Incontinence Including Post Prostatectomy Incontinence: A Challenge to the Urologist. International neurourology journal. 2019 Sep:23(3):185-194. doi: 10.5213/inj.1938108.054. Epub 2019 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 31607097]

Smith WJ, VanDyke ME, Venishetty N, Langford BT, Franzen BP, Morey AF. Surgical Management of Male Stress Incontinence: Techniques, Indications, and Pearls for Success. Research and reports in urology. 2023:15():217-232. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S395359. Epub 2023 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 37366389]

Chung E. Contemporary male slings for stress urinary incontinence: advances in device technology and refinements in surgical techniques. Therapeutic advances in urology. 2023 Jan-Dec:15():17562872231187199. doi: 10.1177/17562872231187199. Epub 2023 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 37528956]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChong JT, Simma-Chiang V. A historical perspective and evolution of the treatment of male urinary incontinence. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2018 Mar:37(3):1169-1175. doi: 10.1002/nau.23429. Epub 2017 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 29053886]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchaeffer AJ, Clemens JQ, Ferrari M, Stamey TA. The male bulbourethral sling procedure for post-radical prostatectomy incontinence. The Journal of urology. 1998 May:159(5):1510-5 [PubMed PMID: 9554344]

Jung J, Ahn HK, Huh Y. Clinical and functional anatomy of the urethral sphincter. International neurourology journal. 2012 Sep:16(3):102-6. doi: 10.5213/inj.2012.16.3.102. Epub 2012 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 23094214]

Wu EH, De Cicco FL. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Male Genitourinary Tract. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965962]

Sam P, Jiang J, Leslie SW, LaGrange CA. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sphincter Urethrae. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494045]

Koraitim MM. The male urethral sphincter complex revisited: an anatomical concept and its physiological correlate. The Journal of urology. 2008 May:179(5):1683-9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.010. Epub 2008 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 18343449]

Schwalenberg T, Neuhaus J, Dartsch M, Weissenfels P, Löffler S, Stolzenburg JU. [Functional anatomy of the male continence mechanism]. Der Urologe. Ausg. A. 2010 Apr:49(4):472-80. doi: 10.1007/s00120-010-2262-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20376649]

Akita K, Sakamoto H, Sato T. Origins and courses of the nervous branches to the male urethral sphincter. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2003 Nov-Dec:25(5-6):387-92 [PubMed PMID: 13680183]

Brooks JD, Chao WM, Kerr J. Male pelvic anatomy reconstructed from the visible human data set. The Journal of urology. 1998 Mar:159(3):868-72 [PubMed PMID: 9474171]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYoham AL, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Inferior Hypogastric Plexus. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33620788]

Yucel S, Baskin LS. An anatomical description of the male and female urethral sphincter complex. The Journal of urology. 2004 May:171(5):1890-7 [PubMed PMID: 15076301]

Myers RP. Practical surgical anatomy for radical prostatectomy. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2001 Aug:28(3):473-90 [PubMed PMID: 11590807]

Shah AP, Mevcha A, Wilby D, Alatsatianos A, Hardman JC, Jacques S, Wilton JC. Continence and micturition: an anatomical basis. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2014 Nov:27(8):1275-83. doi: 10.1002/ca.22388. Epub 2014 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 24615792]

Flores JL, Cortes GA, Leslie SW. Physiology, Urination. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965852]

Heesakkers JP, Gerretsen RR. Urinary incontinence: sphincter functioning from a urological perspective. Digestion. 2004:69(2):93-101 [PubMed PMID: 15087576]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSayner A, Nahon I. Pelvic Floor Muscle Training in Radical Prostatectomy and Recent Understanding of the Male Continence Mechanism: A Review. Seminars in oncology nursing. 2020 Aug:36(4):151050. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151050. Epub 2020 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 32674975]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSingla N, Singla AK. Post-prostatectomy incontinence: Etiology, evaluation, and management. Turkish journal of urology. 2014 Mar:40(1):1-8. doi: 10.5152/tud.2014.222014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26328137]

Dubbelman YD, Bosch JL. Urethral sphincter function before and after radical prostatectomy: Systematic review of the prognostic value of various assessment techniques. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2013 Sep:32(7):957-63. doi: 10.1002/nau.22355. Epub 2013 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 23371847]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBole R, Hebert KJ, Gottlich HC, Bearrick E, Kohler TS, Viers BR. Narrative review of male urethral sling for post-prostatectomy stress incontinence: sling type, patient selection, and clinical applications. Translational andrology and urology. 2021 Jun:10(6):2682-2694. doi: 10.21037/tau-20-1459. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34295753]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFlynn BJ, Webster GD. Evaluation and surgical management of intrinsic sphincter deficiency after radical prostatectomy. Reviews in urology. 2004 Fall:6(4):180-6 [PubMed PMID: 16985599]

Sandhu JS, Breyer B, Comiter C, Eastham JA, Gomez C, Kirages DJ, Kittle C, Lucioni A, Nitti VW, Stoffel JT, Westney OL, Murad MH, McCammon K. Incontinence after Prostate Treatment: AUA/SUFU Guideline. The Journal of urology. 2019 Aug:202(2):369-378. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000314. Epub 2019 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 31059663]

Doudt AD, Zuckerman JM. Male Slings for Post-prostatectomy Incontinence. Reviews in urology. 2018:20(4):158-169. doi: 10.3909/riu080. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30787674]

Fischer MC, Huckabay C, Nitti VW. The male perineal sling: assessment and prediction of outcome. The Journal of urology. 2007 Apr:177(4):1414-8 [PubMed PMID: 17382743]

Cornu JN, Sèbe P, Ciofu C, Peyrat L, Cussenot O, Haab F. Mid-term evaluation of the transobturator male sling for post-prostatectomy incontinence: focus on prognostic factors. BJU international. 2011 Jul:108(2):236-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09765.x. Epub 2010 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 20955265]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGacci M, De Nunzio C, Sakalis V, Rieken M, Cornu JN, Gravas S. Latest Evidence on Post-Prostatectomy Urinary Incontinence. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023 Feb 2:12(3):. doi: 10.3390/jcm12031190. Epub 2023 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 36769855]

Hübner WA, Schlarp OM. Adjustable continence therapy (ProACT): evolution of the surgical technique and comparison of the original 50 patients with the most recent 50 patients at a single centre. European urology. 2007 Sep:52(3):680-6 [PubMed PMID: 17097218]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFuller TW, Ballon-Landa E, Gallo K, Smith TG 3rd, Ajay D, Westney OL, Elliott SP, Alsikafi NF, Breyer BN, Cohen AJ, Vanni AJ, Broghammer JA, Erickson BA, Myers JB, Voelzke BB, Zhao LC, Buckley JC. Outcomes and Risk Factors of Revision and Replacement Artificial Urinary Sphincter Implantation in Radiated and Nonradiated Cases. The Journal of urology. 2020 Jul:204(1):110-114. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000749. Epub 2020 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 31951498]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLarson T, Jhaveri H, Yeung LL. Adjustable continence therapy (ProACT) for the treatment of male stress urinary incontinence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2019 Nov:38(8):2051-2059. doi: 10.1002/nau.24135. Epub 2019 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 31429982]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGacci M, Sakalis VI, Karavitakis M, Cornu JN, Gratzke C, Herrmann TRW, Kyriazis I, Malde S, Mamoulakis C, Rieken M, Schouten N, Smith EJ, Speakman MJ, Tikkinen KAO, Gravas S. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Male Urinary Incontinence. European urology. 2022 Oct:82(4):387-398. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.05.012. Epub 2022 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 35697561]

Lai HH, Hsu EI, Teh BS, Butler EB, Boone TB. 13 years of experience with artificial urinary sphincter implantation at Baylor College of Medicine. The Journal of urology. 2007 Mar:177(3):1021-5 [PubMed PMID: 17296403]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceComiter C. Surgery for postprostatectomy incontinence: which procedure for which patient? Nature reviews. Urology. 2015 Feb:12(2):91-9. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.346. Epub 2015 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 25558839]

Biardeau X, Aharony S, AUS Consensus Group, Campeau L, Corcos J. Artificial Urinary Sphincter: Report of the 2015 Consensus Conference. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2016 Apr:35 Suppl 2():S8-24. doi: 10.1002/nau.22989. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27064055]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHampson LA, Suskind AM, Breyer BN, Lai L, Cooperberg MR, Sudore RL, Keyhani S, Allen IE, Walter LC. Understanding the Health Characteristics and Treatment Choices of Older Men with Stress Urinary Incontinence. Urology. 2021 Aug:154():281-287. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2021.05.002. Epub 2021 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 34004214]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDavuluri M, DeMeo G, Penukonda S, Zahid B, Hu JC. Guiding Clinical Decision Making for Surgical Incontinence Treatment After Prostatectomy: A Review of the Literature. Current urology reports. 2023 Nov:24(11):527-532. doi: 10.1007/s11934-023-01181-6. Epub 2023 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 37768551]

Yanaral F, Gültekin MH, Halis A, Akbulut F, Sarilar O, Ozgor F. Adjustable Male Sling for The Treatment of Postprostatectomy Stress Urinary Incontinence: Intermediate-Term Follow-Up Results. Cureus. 2023 Aug:15(8):e43280. doi: 10.7759/cureus.43280. Epub 2023 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 37692721]

Navalón-Monllor V, Ordoño-Domínguez F, Pallás-Costa Y, Vilar-Castro LA, Monllor-Peidro ME, Juan-Escudero J, Navalón-Verdejo P. Long-term follow-up for the treatment of male urinary incontinence with the Remeex system. Actas urologicas espanolas. 2016 Nov:40(9):585-591. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2016.03.009. Epub 2016 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 27237411]

Rouprêt M, Misraï V, Gosseine PN, Bart S, Cour F, Chartier-Kastler E. Management of stress urinary incontinence following prostate surgery with minimally invasive adjustable continence balloon implants: functional results from a single center prospective study. The Journal of urology. 2011 Jul:186(1):198-203. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.016. Epub 2011 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 21575974]

Guachetá Bomba PL, Ocampo Flórez GM, Echeverría García F, García-Perdomo HA. Effectiveness of surgical management with an adjustable sling versus an artificial urinary sphincter in patients with severe urinary postprostatectomy incontinence: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Therapeutic advances in urology. 2019 Jan-Dec:11():1756287219875581. doi: 10.1177/1756287219875581. Epub 2019 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 31632464]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEsquinas C, Angulo JC. Effectiveness of Adjustable Transobturator Male System (ATOMS) to Treat Male Stress Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Advances in therapy. 2019 Feb:36(2):426-441. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0852-4. Epub 2018 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 30560525]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGiberti C, Gallo F, Schenone M, Cortese P, Ninotta G. The bone anchor suburethral synthetic sling for iatrogenic male incontinence: critical evaluation at a mean 3-year followup. The Journal of urology. 2009 May:181(5):2204-8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.022. Epub 2009 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 19296976]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWinters JC. Male slings in the treatment of sphincteric incompetence. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2011 Feb:38(1):73-81, vi-vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2010.12.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21353082]

Desai TJ, Rozanski AT. Changes and debates in male stress urinary incontinence surgery practice patterns: a contemporary review. Translational andrology and urology. 2023 May 31:12(5):918-925. doi: 10.21037/tau-22-646. Epub 2023 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 37305630]

Chung ASJ, Suarez OA, McCammon KA. AdVance male sling. Translational andrology and urology. 2017 Aug:6(4):674-681. doi: 10.21037/tau.2017.07.29. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28904900]

Inouye BM, Premo HA, Weil D, Peterson AC. The male sling for stress urinary incontinence: tips and tricks for success. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2021 Nov-Dec:47(6):1131-1135. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2020.1122. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33861057]

Sousa-Escandón A, Rodríguez Gómez JI, Uribarri González C, Marqués-Queimadelos A. Externally readjustable sling for treatment of male stress urinary incontinence: points of technique and preliminary results. Journal of endourology. 2004 Feb:18(1):113-8 [PubMed PMID: 15006064]

Rapp DE, Reynolds WS, Lucioni A, Bales GT. Surgical technique using AdVance sling placement in the treatment of post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2007 Mar-Apr:33(2):231-5; discussion 236-7 [PubMed PMID: 17488544]

Meisterhofer K, Herzog S, Strini KA, Sebastianelli L, Bauer R, Dalpiaz O. Male Slings for Postprostatectomy Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. European urology focus. 2020 May 15:6(3):575-592. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2019.01.008. Epub 2019 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 30718160]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYe H, Haab F, de Ridder D, Chauveau P, Becker A, Arano P, Haillot O, Fassi-Fehri H. Effectiveness and Complications of the AMS AdVance™ Male Sling System for the Treatment of Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Urology. 2018 Oct:120():197-204. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.06.035. Epub 2018 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 30404760]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRizvi IG, Ravindra P, Pipe M, Sohawon R, King T, Belal M. The AdVance™ male sling: does it stand the test of time? Scandinavian journal of urology. 2021 Apr:55(2):155-160. doi: 10.1080/21681805.2021.1877342. Epub 2021 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 33517819]

Ghaffar U, Abbasi B, Fuentes JLG, Sudhakar A, Hakam N, Smith A, Jones C, Shaw NM, Breyer BN. Urethral Slings for Irradiated Patients With Male Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Meta-analysis. Urology. 2023 Oct:180():262-269. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2023.07.022. Epub 2023 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 37543118]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBauer RM, Grabbert MT, Klehr B, Gebhartl P, Gozzi C, Homberg R, May F, Rehder P, Stief CG, Kretschmer A. 36-month data for the AdVance XP(®) male sling: results of a prospective multicentre study. BJU international. 2017 Apr:119(4):626-630. doi: 10.1111/bju.13704. Epub 2016 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 27862836]

Collado Serra A, Resel Folkersma L, Domínguez-Escrig JL, Gómez-Ferrer A, Rubio-Briones J, Solsona Narbón E. AdVance/AdVance XP transobturator male slings: preoperative degree of incontinence as predictor of surgical outcome. Urology. 2013 May:81(5):1034-9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.01.007. Epub 2013 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 23465151]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceComiter CV, Rhee EY, Tu LM, Herschorn S, Nitti VW. The virtue sling--a new quadratic sling for postprostatectomy incontinence--results of a multinational clinical trial. Urology. 2014 Aug:84(2):433-8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.02.062. Epub 2014 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 24972946]

Khouri RK Jr, Ortiz NM, Baumgarten AS, Ward EE, VanDyke ME, Hudak SJ, Morey AF. Artificial Urinary Sphincter Outperforms Sling for Moderate Male Stress Urinary Incontinence. Urology. 2020 Jul:141():168-172. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.03.028. Epub 2020 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 32289365]

Siracusano S, Visalli F, Favro M, Tallarigo C, Saccomanni M, Kugler A, Diminutto A, Talamini R, Artibani W. Argus-T Sling in 182 Male Patients: Short-term Results of a Multicenter Study. Urology. 2017 Dec:110():177-183. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.07.058. Epub 2017 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 28917606]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRocha FT, Lesting JFP. Salvage surgical procedure for artificial sphincter extrusion. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2018 May-Jun:44(3):634-638. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2017.0462. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29412549]

Montague DK. Artificial urinary sphincter: long-term results and patient satisfaction. Advances in urology. 2012:2012():835290. doi: 10.1155/2012/835290. Epub 2012 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 22536227]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceComiter CV, Dobberfuhl AD. The artificial urinary sphincter and male sling for postprostatectomy incontinence: Which patient should get which procedure? Investigative and clinical urology. 2016 Jan:57(1):3-13. doi: 10.4111/icu.2016.57.1.3. Epub 2016 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 26966721]

Trost L, Elliott DS. Male stress urinary incontinence: a review of surgical treatment options and outcomes. Advances in urology. 2012:2012():287489. doi: 10.1155/2012/287489. Epub 2012 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 22649446]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLavi A, Boone TB, Cohen M, Gross M. The Patient Beyond the Sphincter-Cognitive and Functional Considerations Affecting the Natural History of Artificial Urinary Sphincters. Urology. 2020 Mar:137():14-18. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2019.11.031. Epub 2019 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 31794813]