Introduction

The infraclavicular block is a brachial plexus block used as an alternative or adjunct to general anesthesia. It can be used for postoperative pain control for upper extremity surgeries such as the elbow, forearm, and hand, but not the shoulder.

The infraclavicular block is a regional anesthetic technique developed to avoid the side effects and complications of supraclavicular blocks, particularly pneumothorax. The infraclavicular block is a regional anesthetic technique designed to prevent the side effects and complications of supraclavicular blocks, particularly pneumothorax. The advantage of an infraclavicular block is decreased complications with ultrasound, and it is ideally suited for catheter usage. The disadvantage is that the brachial plexus is located deeper and the angle of approach is more acute making visualization of the anatomy and handling a needle at the same time challenging unless the healthcare professional is experienced in performing the procedure. The procedure is also challenging in patients with obesity for these same reasons.[1]

Bazy first described the infraclavicular block in 1914, and Speigel described the infraclavicular trans-pectoral perivascular technique in 1967.[2] Raj[3] modified the technique and reported a new approach with higher success rates using a nerve stimulator in 1973. Sims developed the lateral infraclavicular block in 1976 to present a more consistent performance with a constant landmark: the coracoid process.[4] Many approaches have been described since that time, but the most frequent approach today is a sagittal scan at the lateral infraclavicular fossa (LICF).[5]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The ventral rami of C5 to C8 and T1 nerve roots for the brachial plexus. These roots exit the intervertebral foramina to form the superior, middle, and inferior trunks that travel between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. Each trunk divides into an anterior and posterior division behind the clavicle and emerges from under the clavicle to form the lateral, posterior, and medial cords, named according to their relative position to the axillary artery. The cords then split into the five terminal nerve branches. The infraclavicular block is executed below the clavicle at the cord level of the brachial plexus. The axillary vessels and the cords of the brachial plexus lie deep to the pectoralis muscles, inferior and slightly medial to the coracoid process. When the cords appear below the clavicle approximately at its midpoint, it initially runs laterally between the clavicle (cephalad) and the artery (caudally) where the vertical ICB can block it. As it passes laterally, the cords position themselves cephalo-laterally to the artery and then wraps around the artery to gain its exact anatomical position in the axilla with the cords lying lateral, posterior, and medial to the axillary artery. Boundaries include the pectoralis minor and major muscles anteriorly, ribs medially, clavicle and the coracoid process superiorly, and humerus laterally are the. The anatomy of the plexus varies widely. An MRI study by Sauter[6] showed that the cords are located within 2 cm from the center of the axillary artery, approximately within two-thirds of a circle. When visualizing a clock face, the axillary artery is at the center, and the cords are between 3 and 11 o’clock.

Indications

The infraclavicular block is designated for regional anesthesia for surgery or postoperative pain control of the upper extremity and is suitable for hand, wrist, elbow, and distal arm surgery. The shoulder area is not covered since the superficial cervical plexus C1 to C4 innervates it. The skin of the axilla and proximal medial arm requires an additional intercostobrachial nerve block to provide full anesthesia. There may also be incomplete radial nerve sensory block.[7]

Contraindications

There are no block-specific contraindications to infraclavicular block. Absolute contraindications to peripheral nerve blocks include patient refusal, allergy to local anesthetics, and infection at the injection site. Coagulopathy and preexisting active neurologic deficits are relative contraindications.

Equipment

The necessary equipment includes:

- Chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine

- High-frequency ultrasound probe with a sterile probe cover and gel (recommended)

- Sterile towels, gauze packs, sterile gloves, marking pen

- Local anesthetic for skin infiltration, typically 1% lidocaine in 3mL syringe + 25-gauge needle

- Short-bevel, insulated-stimulating, block needle 10-cm; 18-gauge for a continuous catheter, 21-gauge for single-injection

- Peripheral nerve stimulator (optional)

- Two, 20-mL syringes containing local anesthetic for block

- Regional block local anesthetic solution (0.5% bupivacaine or 0.5% ropivacaine for postoperative analgesia, and 2% lidocaine or 1.5% mepivacaine when shorter onset times are a necessity)

- Intralipid 20% in the case of Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity (LAST)

Personnel

Personnel includes practitioners trained in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. A block often requires 2 people. One person will have control of the ultrasound probe and needle, and another person will manage the nerve stimulator as well as the syringe with local anesthetic medications. Additional personnel is needed to monitor patient vital signs and administer rescue medications if needed.

Preparation

In preparation for the procedure, 3-lead ECG, pulse oximeter, and noninvasive blood pressure monitoring are placed. The provider must complete informed consent. A pre-procedure time-out is performed, and the patient lies in the supine position with their head turned away from the side to be blocked. The arm can be in any position, although to bring the cords closer to the surface it may be advantageous to abduct the patient’s arm and flex at the elbow to maintain the relationship of the landmarks to the brachial plexus. The wrist should be supported to visualize and interpret twitches of the hand if a nerve stimulator is used. Nerve stimulation is often painful, so light sedation and analgesia are recommended for patient comfort. A short-acting narcotic can be administered before needle insertion as the needle passing through the pectoralis muscle is moderately painful.

Technique or Treatment

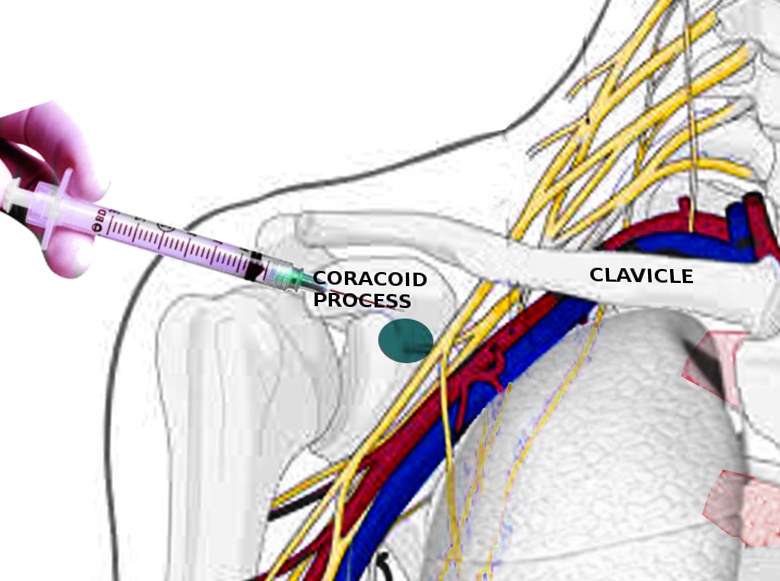

Since Raj and Sims, many techniques have been described over the years with varying needle insertion points, surface landmarks, and recommended needle directions. The 3 most common approaches are the coracoid approach, lateral sagittal approach, and a vertical approach. Others include the parasagittal, pericoracoid, and retrograde approaches.[8]

The practitioner identifies the coracoid process by palpating the bony prominence just medial to the shoulder while raising the patient's arm is raised and lowered. He or she then identifies the medial clavicular head and draws a line connecting the 2 landmarks and mark the midpoint.

The coracoid method has been described with the needle insertion 2-cm medial and 2-cm inferior to the coracoid process and directed from ventral to dorsal. The practitioner encounters the cords at an average depth of 4.5 cm.

In the parasagittal approach, the practiotiner inserts the needle immediately below the clavicle into the groove between the coracoid process and the clavicle and passes from the cephalad to caudal with the cords 5- to 6-cm deep. Identification of the arterial pulse on the sonographic image is an easy primary goal in establishing the landmark when using the ultrasound-guided approach. In the retroclavicular approach, the needle insertion point is posterior to the clavicle, not inferior. The professional inserts the needle directly above the clavicle in the space between the coracoid process and the clavicle and advances from cephalad to caudad.[8]

Kilka described the vertical infraclavicular block (VIB) of the brachial plexus, which is commonly used to provide analgesia of the upper limb because it is simple, reliable, and safe due to clearly defined anatomic landmarks.[9] In the original method, the practioner perforeming the block inserts the needle anteroposteriorly, immediately caudal to the middle of the clavicle at the mid-point of an infraclavicular line between the acromion and jugular fossa. With the use of ultrasound for nerve blocks, the practitioner can recognixe the anatomy of the target and the surrounding structures and plan the optimal puncture site and pathway.

Ultrasonography has enabled experimental research and new techniques. There are modified versions of VIB, including the modified Greher and Neuberger VIB methods. Greher’s modified method showed 22 cm as the optimal length from acromion to jugular fossa. Patients with shorter length required the optimal injection point to be moved 0.2-cm laterally for each centimerter less than 22 cm and 0.2 cm medially for each cenitmeter of length greater than 22 cm.[10] Another modern study by Neuburger showed 20 cm as the optimal length and that patients with length shoter than 20 cm required the injection point to be moved 0.3-cm laterally for each centimeter below 20 cm.[11]

In 2004, Klaastad suggested that an infraclavicular block can be accomplished by the lateral sagittal route (lateral sagittal infraclavicular block [LSIB]) with ease and low complications risk. In this method, a finger is slid laterally below the clavicle until the medial surface of the coracoid process is recognized. The needle is inserted tangentially to the anteroinferior border of the clavicle and directed 15-degrees posterior to the horizontal (coronal) plane. The needle is advanced to a maximum of 6.5 cm strictly in the sagittal plane next to the coracoid process.[12]

Due to limitations of LSIB, for example, the depth of the cords and separation from each other, as well as significant variations in the position of the cords, a new technique has emerged: the costoclavicular approach. Ultrasound-guided, costoclavicular approach is found to be an alternative way of providing effective analgesia and safe anesthesia for vascular access surgery of the upper limb.[13] The costoclavicular space (CCS) is the intermuscular space located deep and posterior to the midpoint of the clavicle and between the clavicular head of the pectoralis major and subclavius muscle anteriorly and the second rib posteriorly.[5] The advantages proposed at the CCS is the cords are clustered together lateral to the axillary artery with a consistent relationship to one another.[14] A single injection with a smaller volume of local anesthetic can be used with a successful block.[5] Utilizing this technique, a transverse scan is performed below the midpoint of the clavicle and over the medial infraclavicular fossa with the transducer tilted cephalad creating an image with all 3 cords visualized. The block needle is inserted in-plane in a lateral to medial direction.[5] In a comparative study, the costoclavicular approach produced a faster onset of sensory blockade and earlier readiness for surgery than the LSIB approach.[15]

Complications

Possible complications of infraclavicular nerve blocks vary between each technique and volume of LA used but may include:

- Infection

- Bleeding: Lesser potential risk in coagulopathic patients with a costoclavicular technique[16]

- Hematoma

- Vascular puncture

- Needle induced paresthesia

- Nerve injury

- Intravascular/intraneural injection

- Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity (LAST)

- Allergic reactions

- Horner syndrome

- Hemidiaphragmatic paralysis

- Pneumothorax

Clinical Significance

Infraclavicular brachial plexus blocks are a substitute for supraclavicular and axillary blocks used for surgery below the shoulder, and when positioning is restricted due to limited abduction at the shoulder. The infraclavicular area is the best site for catheter placement because it is deep and the pectoral muscles keep the catheter in place preventing dislodgement. This block has fallen out of favor because it is more difficult to visualize the target structures due to the depth and has mainly been used when surgery necessitates catheter insertion. When comparing supraclavicular block (SCB), infraclavicular block (ICB), and axillary block, there is a similar quality of surgical anesthesia for operations below the shoulder.[17] With advances in ultrasound, new techniques are being discovered and redefining the benefits of infraclavicular blocks.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There are a variety of brachial plexus blocks. Knowing how to perform these procedures, including the limitations of each technique is beneficial. Often a surgeon may prefer a specific type of brachial plexus block. The advantages of infraclavicular block include comprehensive upper extremity anesthesia, a lower incidence of tourniquet pain, and a preferable site for catheter insertion making it the preferred approach to brachial plexus blockade.[18] There are rare case reports of pneumothorax[19] and hemidiaphragmatic paralysis,[20](Level V) but this remains less than with other approaches. Ultrasound guidance shows improved performance time, success rate, and decrease the risk of associated complications. A comprehensive, retrospective study of 1146 patients who received US-guided ICB had a success rate of 99.3%, with no reported cases of nerve injury, pneumothorax, or local anesthetic toxicity.[21] (Level I)

The nurse is an integral part of the team as she or he will monitor for complications during and after the procedure including hematoma, bleeding at the puncture site, and paresthesias. (Level V) Continuous catheters can be safely secured to the upper chest wall and monitored by nurses. An interprofessional approach will provide the best patient outcomes.

Media

References

Abhinaya RJ,Venkatraman R,Matheswaran P,Sivarajan G, A randomised comparative evaluation of supraclavicular and infraclavicular approaches to brachial plexus block for upper limb surgeries using both ultrasound and nerve stimulator. Indian journal of anaesthesia. 2017 Jul [PubMed PMID: 28794531]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSpiegel P, [Block of the brachial plexus. Infraclavicular transpectoral perivascular technic]. Revista brasileira de anestesiologia. 1967 Jan-Mar [PubMed PMID: 5595548]

Raj PP,Montgomery SJ,Nettles D,Jenkins MT, Infraclavicular brachial plexus block--a new approach. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1973 Nov-Dec [PubMed PMID: 4796563]

Sims JK, A modification of landmarks for infraclavicular approach to brachial plexus block. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1977 Jul-Aug [PubMed PMID: 560144]

Li JW,Songthamwat B,Samy W,Sala-Blanch X,Karmakar MK, Ultrasound-Guided Costoclavicular Brachial Plexus Block: Sonoanatomy, Technique, and Block Dynamics. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2017 Mar/Apr [PubMed PMID: 28157792]

Sauter AR,Smith HJ,Stubhaug A,Dodgson MS,Klaastad Ø, Use of magnetic resonance imaging to define the anatomical location closest to all three cords of the infraclavicular brachial plexus. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2006 Dec [PubMed PMID: 17122242]

Park SK,Lee SY,Kim WH,Park HS,Lim YJ,Bahk JH, Comparison of Supraclavicular and Infraclavicular Brachial Plexus Block: A Systemic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2017 Feb [PubMed PMID: 27828793]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKavrut Ozturk N,Kavakli AS, Comparison of the coracoid and retroclavicular approaches for ultrasound-guided infraclavicular brachial plexus block. Journal of anesthesia. 2017 Aug [PubMed PMID: 28421316]

Sharma D,Srivastava N,Pawar S,Garg R,Nagpal VK, Infraclavicular brachial plexus block: Comparison of posterior cord stimulation with lateral or medial cord stimulation, a prospective double blinded study. Saudi journal of anaesthesia. 2013 Apr [PubMed PMID: 23956710]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGreher M,Retzl G,Niel P,Kamolz L,Marhofer P,Kapral S, Ultrasonographic assessment of topographic anatomy in volunteers suggests a modification of the infraclavicular vertical brachial plexus block. British journal of anaesthesia. 2002 May [PubMed PMID: 12066998]

Neuburger M,Kaiser H,Ass B,Franke C,Maurer H, [Vertical infraclavicular blockade of the brachial plexus (VIP). A modified method to verify the puncture point under consideration of the risk of pneumothorax]. Der Anaesthesist. 2003 Jul [PubMed PMID: 12898048]

Klaastad Ø,Smith HJ,Smedby O,Winther-Larssen EH,Brodal P,Breivik H,Fosse ET, A novel infraclavicular brachial plexus block: the lateral and sagittal technique, developed by magnetic resonance imaging studies. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2004 Jan [PubMed PMID: 14693630]

Beh ZY,Hasan MS, Ultrasound-guided costoclavicular approach infraclavicular brachial plexus block for vascular access surgery. The journal of vascular access. 2017 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 28478621]

Sala-Blanch X,Reina MA,Pangthipampai P,Karmakar MK, Anatomic Basis for Brachial Plexus Block at the Costoclavicular Space: A Cadaver Anatomic Study. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2016 May-Jun [PubMed PMID: 27035461]

Songthamwat B,Karmakar MK,Li JW,Samy W,Mok LYH, Ultrasound-Guided Infraclavicular Brachial Plexus Block: Prospective Randomized Comparison of the Lateral Sagittal and Costoclavicular Approach. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2018 Nov [PubMed PMID: 29923950]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeurcharusmee P,Elgueta MF,Tiyaprasertkul W,Sotthisopha T,Samerchua A,Gordon A,Aliste J,Finlayson RJ,Tran DQH, A randomized comparison between costoclavicular and paracoracoid ultrasound-guided infraclavicular block for upper limb surgery. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2017 Jun [PubMed PMID: 28205117]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStav A,Reytman L,Stav MY,Portnoy I,Kantarovsky A,Galili O,Luboshitz S,Sevi R,Sternberg A, Comparison of the Supraclavicular, Infraclavicular and Axillary Approaches for Ultrasound-Guided Brachial Plexus Block for Surgical Anesthesia. Rambam Maimonides medical journal. 2016 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 27101216]

Chin KJ,Alakkad H,Adhikary SD,Singh M, Infraclavicular brachial plexus block for regional anaesthesia of the lower arm. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 23986434]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCrews JC,Gerancher JC,Weller RS, Pneumothorax after coracoid infraclavicular brachial plexus block. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2007 Jul [PubMed PMID: 17578988]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYang CW,Jung SM,Kwon HU,Kang PS,Cho CK,Choi HJ, Transient hemidiaphragmatic paresis after ultrasound-guided lateral sagittal infraclavicular block. Journal of clinical anesthesia. 2013 Sep [PubMed PMID: 23965197]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSandhu NS,Manne JS,Medabalmi PK,Capan LM, Sonographically guided infraclavicular brachial plexus block in adults: a retrospective analysis of 1146 cases. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2006 Dec [PubMed PMID: 17121950]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence