Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Levator Ani Muscle

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Levator Ani Muscle

Introduction

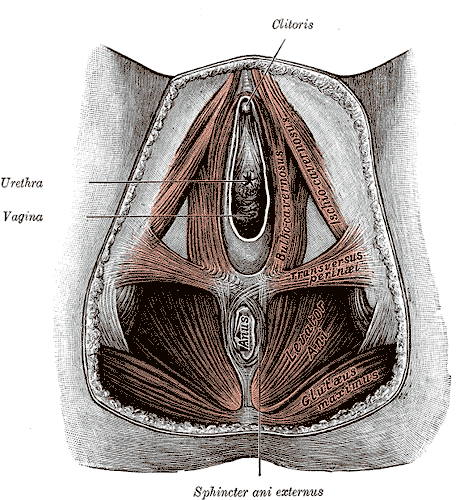

The levator ani is a complex funnel-shaped structure mainly composed of striated muscle with some smooth muscle components (see Image. Female Perineum).[1] Located on either side of the lower pelvis, it supports and raises the pelvic floor and allows various pelvic structures to pass through it. The levator ani muscle and the coccygeus muscle are part of the pelvic floor. It forms from the confluence of 3 muscles: puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus muscles. These mostly receive innervation by the somatic nerves from the sacral plexus, namely the pudendal nerve and nerve of the levator ani muscle, and autonomic nerves from the inferior hypogastric plexus.[2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The major function of the levator ani muscle is supporting and raising the pelvic visceral structures. It also helps in proper sexual functioning, defecation, and urination and allows various structures to pass through it. The levator ani muscle comprises 3 parts: puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and the iliococcygeus muscle.

Origin, Course, and Insertion

Arcus tendinous fascia pelvis covers the medical aspect of the obturator internus muscle, the posterior part of this thickened fibrous fascia forms the arcus tendineus levator ani, which is the origin of the iliococcygeus part of the levator ani muscle. The muscle passes backward and downwards the midline, the posterior fibers insert into the coccyx, and the anterior fibers into the anococcygeal raphe or body.[3] Puborectalis originates from the inferior part of the pubic symphysis and the superior fascial layer of the urogenital diaphragm. It then courses backward, forms a sling around the rectum, and meets the fibers from the opposite muscle at the midline. Pubococcygeus originates from the posterior aspect of the pubis' inferior rami and the obturator fascia's anterior part. It passes back towards the midline and inset into the anococcygeal raphe. It has variation depending on the gender, where it inserts to either the vagina as pubovaginalis muscle in females or the prostate as puboprostaticus muscle in males.

Structure and Function

The puborectalis muscle forms a sling around the lower rectum when it meets the fibers from the opposite side. It acts in association with the internal and external anal sphincter in the process of defecation. The pubococcygeus muscle controls the flow of urine. Also, it helps reduce urinary incontinence, where a weaker pubococcygeus muscle is seen in a higher number of urinary incontinence patients, especially in gravid and post-gravid women. The pubovaginalis muscle in females and the male counterpart, levator prostate (also called puboprostaticus), form the medial part of the pubococcygeus and function to support the vagina in females and prostate in males, respectively. It aids in ejaculation in males, assists childbirth in the proper positioning of the fetus's head, and provides core stability.[4]

The iliococcygeus forms the midline raphe after it meets the fibers from the opposite side. It is continuous with the anococcygeal ligament and provides a secure anchoring point for the pelvic floor. Collective as the levator ani muscle, it gives structural support to abdominopelvic visceral organs, helps maintain intraabdominal pressure, assists during respiration, and aids in defecation and urination.[5] The levator ani muscle helps to manage mechanical pressures during movement. It is important for the distribution of loads during walking and trunk and limb movements. The upper breathing centers control the muscle during breathing; during inhalation, it releases, while during exhalation, it contracts. A 2012 study showed that the levator ani muscle directly connects with the gluteus maximus muscle via a connective tissue bridge at the level of the ischioanal fossa.

Embryology

The levator ani muscle represents the evolutionary byproduct remnants of tailed mammalians. Muscle development is apparent as early as the ninth week of fetal life, where the rudimentary forms begin to form and can already be separated into 3 parts by loose mesenchyme. It is derived from the pubocaudal group of muscles. The distinctive funnel shape is visible in the fourteenth week of fetal life. By the second trimester, the differences in the male and female forms of the levator ani muscles become more evident. Pubococcygeus and the iliococcygeus get differentiated with the help of the tendinous arch. The embryological sheet from which this muscle complex derives is the mesoderm.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the levator ani muscle comes from different branches of the inferior gluteal artery, inferior vesical artery, and pudendal artery. Venous drainage and lymphatic drainage are along the corresponding veins accompanying the arteries.

Nerves

The primary nerve supply is from the nerves originating from the S3 and S4, with fibers from the S2 and coccygeus plexus. The nerve to levator ani is a part of the pudendal plexus, originating from the fourth sacral spinal nerve. These muscles also receive fibers from the inferior rectal nerve, a branch of the pudendal nerve, and a few fibers of the coccygeus plexus. There are no bilateral innervations of the muscles.[6][7] A 2017 study highlighted the complex innervation of the levator ani in the human fetus. The study divided the innervation into 3 portions: the superficial portion is innervated by the levator ani nerve (somatic function); the lower portion receives innervation by the pudendal nerve (somatic and autonomic function); the portion between the muscle and nerve supply to the pelvic viscera is from the inferior hypogastric plexus nerve fibers (autonomic function).

Muscles

The levator ani muscle consists of the following parts [8]:

- Pubococcygeus

- Pubovaginalis

- Puboprostaticus

- Puboperineal

- Puboanal

- Puborectalis

- Illiococcygeus

However, We must remember that the current anatomical literature does not agree in describing the complexity of the levator ani and the pelvic floor muscles. There is the pelvic diaphragm, the urogenital diaphragm, the endopelvic fascia, the visceral and somatic ligaments, and the ischiococcygeus muscle. Furthermore, the vectors of the muscle fibers, according to tractography studies, demonstrate how a highly chaotic orientation exists; this arrangement allows an optimal ability to adapt to different functional requests.

Physiologic Variants

There exists some variation in the nerve supply, ranging from the direct supply by the fourth sacral spinal nerve to supply from the coccygeal plexus.[6] Studies using magnetic resonance imaging on female patients have revealed several morphologic variants (thinning or aplasia) of the levator ani complex.

Surgical Considerations

There are various reasons for a surgical approach to the levator ani (tumors, repairs, trauma, prolapses, and more) and various surgical techniques (these depend on the site of the intervention, the choice of the surgeon, the subjective need, and more). In general, the decision to undergo surgical intervention is based on the impossibility of following non-invasive management.

Clinical Significance

Levator Ani Syndrome

It results from the spasmodic contraction of the levator ani muscle. It is characterized by recurrent and chronic burning pain, pressure, tenesmus, or discomfort without any detectable organic pathology. It is felt in the rectal, sacral, and coccygeal regions, sometimes radiating to the thigh or the gluteal region. The diagnosis is mostly clinical, where the pain is exaggerated when sitting and is relieved when lying down or standing up. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and is diagnosable by the Rome III criteria for diagnosis of levator ani syndrome:

- Chronic or recurrent rectal pain or aching

- Episodes lasting for 20 min or longer

- Exclusion of other causes of rectal pain such as ischemia, inflammatory bowel disease, cryptitis, intramuscular abscess, anal fissure, hemorrhoids, prostatitis, and coccygodynia.

- Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis

- Tenderness during posterior traction of the puborectalis muscle

Points 1 to 4 mentioned above are the diagnostic criteria for chronic proctalgia, whereas tenderness of the puborectalis muscle (point 5) is the differentiating factor. The Rome IV update on Colorectal Disorders hasn't changed the above-mentioned diagnostic criteria.[9] There is no specific single treatment that is successful for all patients. Reassurance regarding the benign nature of the disease should come first. Then, the range of treatment would include digital massage, muscle relaxants, sitz baths, biofeedback, and electro-galvanic stimulation.[10]

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

It is the descent of 1 or more of the pelvic organs out of the pelvis; it can either be the anterior vaginal wall with the bladder as its contents, the posterior vaginal wall with the rectum, the uterus, or the vaginal vault. Prolapse can cause dysfunction in activities of daily living, exercising, and sexual functioning. Its cause is multifactorial, but the most common factor would be pregnancy. Other risk factors include prior obstetric procedures or pelvic surgeries, chronic cough or straining, repeated heavy lifting, genetics, and ethnicity. The weakening of the levator ani muscle is the most common pathophysiology, where the funnel shape is altered and is more vertically oriented, causing the widening of the opening for the vagina.[11] Clinical features of levator ani syndrome include the following:

- Urinary stress incontinence

- Defecation symptoms: Fecal incontinence and constipation

- Altered sexual function and may cause dyspareunia

- A sensation of bulge or pressure symptoms in the vaginal vault

As most cases of pelvic organ prolapse are asymptomatic, observation can be the treatment of choice, with lifestyle modification regarding smoking cessation, avoiding heavy lifting, and correcting constipation being helpful. Pelvic floor muscle training, also known as Kegel exercises, is performed by repeatedly contracting and relaxing the muscles of the pelvic floor made up of the levator ani and coccygeus muscle. It is done several times daily, lasting for a few minutes each time, for 2 to 3 months, to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles. Invasive methods like pessaries and surgical correction can be options for the treatment of a severe form of prolapse.

Other Issues

The levator ani nerve can suffer injury during certain pelvic reconstruction surgeries and parturition. Physiotherapy at the levator ani muscle is recommended for problems related to childbirth or the presence of muscle weakness that could lead to visceral prolapse or in cases of incontinence.[12] [13][14]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Anatomy of the Female Perineum. The female perineum comprises key anatomical structures, including the clitoris, urethra, vagina, sphincter ani externus, anus, gluteus maximus, levator ani, and transversus perinei.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Němec M, Horčička L, Krofta L, Feyereisel J, Dibonová M. Anatomy and biomechanic of the musculus levator ani. Ceska gynekologie. 2019 Summer:84(5):393-397 [PubMed PMID: 31826638]

Nyangoh Timoh K, Moszkowicz D, Zaitouna M, Lebacle C, Martinovic J, Diallo D, Creze M, Lavoue V, Darai E, Benoit G, Bessede T. Detailed muscular structure and neural control anatomy of the levator ani muscle: a study based on female human fetuses. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jan:218(1):121.e1-121.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.09.021. Epub 2017 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 28988909]

Narducci F, Occelli B, Hautefeuille J, Cosson M, Francke JP, Querleu D, Crépin G. [Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis: anatomical study]. Journal de gynecologie, obstetrique et biologie de la reproduction. 2000 Nov:29(7):644-9 [PubMed PMID: 11119035]

Wu QK,Mao XY,Luo LM,Ying T,Li Q,Teng YC, [Characteristics of pelvic diaphragm hiatus in pregnant women with stress urinary incontinence detected by transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound]. Zhonghua fu chan ke za zhi. 2010 May; [PubMed PMID: 20646439]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEmerich Gordon K, Reed O. The Role of the Pelvic Floor in Respiration: A Multidisciplinary Literature Review. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2020 Mar:34(2):243-249. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.09.024. Epub 2018 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 30447797]

Grigorescu BA, Lazarou G, Olson TR, Downie SA, Powers K, Greston WM, Mikhail MS. Innervation of the levator ani muscles: description of the nerve branches to the pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and puborectalis muscles. International urogynecology journal and pelvic floor dysfunction. 2008 Jan:19(1):107-16 [PubMed PMID: 17565421]

Percy JP, Neill ME, Swash M, Parks AG. Electrophysiological study of motor nerve supply of pelvic floor. Lancet (London, England). 1981 Jan 3:1(8210):16-7 [PubMed PMID: 6109050]

Zijta FM, Lakeman MM, Froeling M, van der Paardt MP, Borstlap CS, Bipat S, Montauban van Swijndregt AD, Strijkers GJ, Roovers JP, Nederveen AJ, Stoker J. Evaluation of the female pelvic floor in pelvic organ prolapse using 3.0-Tesla diffusion tensor imaging and fibre tractography. European radiology. 2012 Dec:22(12):2806-13. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2548-5. Epub 2012 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 22797954]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSimren M, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Update on Rome IV Criteria for Colorectal Disorders: Implications for Clinical Practice. Current gastroenterology reports. 2017 Apr:19(4):15. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0554-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28374308]

Ng CL. Levator ani syndrome - a case study and literature review. Australian family physician. 2007 Jun:36(6):449-52 [PubMed PMID: 17565405]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIglesia CB, Smithling KR. Pelvic Organ Prolapse. American family physician. 2017 Aug 1:96(3):179-185 [PubMed PMID: 28762694]

Juez L,Núñez-Córdoba JM,Couso N,Aubá M,Alcázar JL,Mínguez JÁ, Hypopressive technique versus pelvic floor muscle training for postpartum pelvic floor rehabilitation: A prospective cohort study. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2019 Sep [PubMed PMID: 31297874]

Legendre G, Gonzalves A, Levaillant JM, Fernandez D, Fuchs F, Fernandez H. Impact of at-home self-rehabilitation of the perineum on pelvic floor function in patients with stress urinary incontinence: Results from a prospective study using three-dimensional ultrasound. Journal de gynecologie, obstetrique et biologie de la reproduction. 2016 Feb:45(2):139-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2015.07.001. Epub 2015 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 26321621]

Woodley SJ, Boyle R, Cody JD, Mørkved S, Hay-Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Dec 22:12(12):CD007471. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007471.pub3. Epub 2017 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 29271473]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence