Introduction

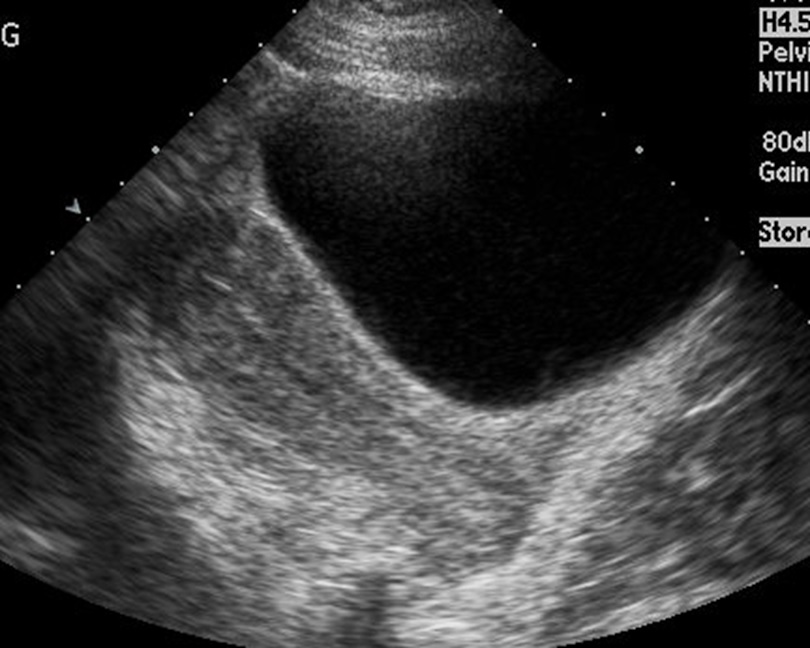

Ectopic pregnancy is a diagnosis that is quite challenging to make. It has been estimated that 40% of ectopic pregnancies go undiagnosed on initial presentation.[1] Ectopic pregnancy is also a very difficult condition to identify based on history and physical, with both the history and physical examination features being neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis. Data suggests that even experienced gynecologists are unable to detect more than half of the masses created by ectopic pregnancy on physical exam.[2] Due to the nature of the condition, laboratory data and diagnostic imaging are essential components of diagnosing ectopic pregnancy. Ultrasonography is the diagnostic imaging study of choice for ectopic pregnancy (see Image. Ectopic Pregnancy, Ultrasound). Even if an ectopic pregnancy cannot be visualized on ultrasound, diagnosing an intrauterine pregnancy greatly reduces the risk of an ectopic pregnancy being present. Two ultrasonographical approaches exist for the evaluation of ectopic pregnancy. The first is the less invasive transabdominal ultrasound, and the second is the more invasive but more diagnostic endovaginal ultrasonography.[3][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

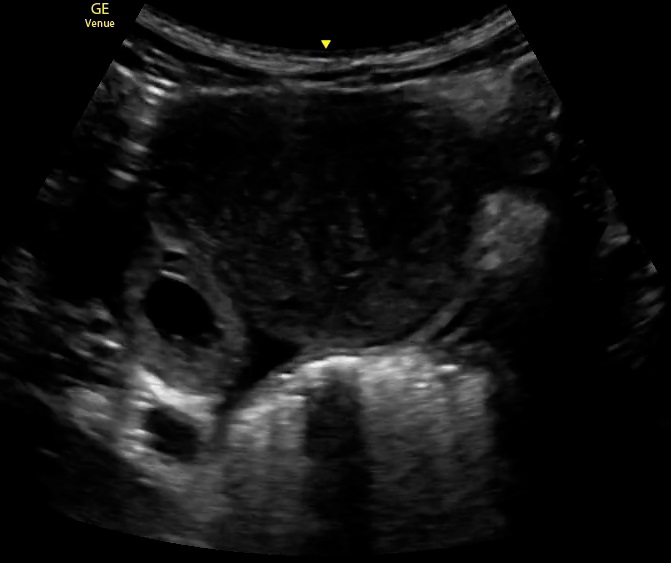

As a basic anatomical review, the introitus is the vaginal canal, where the cervix of the uterus leads into the main body. Bilateral fallopian tubes and fimbria lead to the ovaries. An anatomical understanding is necessary when reviewing the ultrasound images and clips to understand what are normal and abnormal structures. See Image. Ectopic Pregnancy Gestation Sac, Ultrasound.

The common location of ectopic pregnancies differs between whether the patient had a natural conception or assisted reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilization. In natural conception, 95% of the ectopic pregnancies will be tubal, 1.4% will be abdominal, and less than 1% will be cervical or ovarian. With assisted reproductive technologies, 82% of ectopic pregnancies will be tubal with a primary ampullary predominance. Approximately 11% of ectopic pregnancies after assisted reproductive technologies will be heterotopic, which is a vast difference from natural conception. Understanding these differences stresses the importance of obtaining a history of the method of conception.

Indications

If the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is being considered, ultrasonography is an essential part of the diagnostic evaluation. Ectopic pregnancy must be considered as a potentially life-threatening diagnosis in any woman of childbearing age presenting with abdominal pain, pelvic pain, or vaginal bleeding. If a beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is positive, an ectopic pregnancy must rise on a differential and be ruled out before a patient can be safely sent home. If the beta hCG is negative, an ectopic pregnancy is much less likely, but there have been rare case reports of ectopic pregnancies being identified in this state, notably when a qualitative urine beta hCG is ordered rather than a quantitative serum beta hCG level.[5]

Contraindications

There is only one absolute contraindication to transvaginal ultrasonography, and there are no absolute contraindications to transabdominal imaging. The contraindication for transvaginal imaging is recent gynecologic surgery, which is an exceedingly rare situation for patients potentially in their first trimester. Special considerations should be made when determining how the imaging should be completed. Obesity potentially limits the diagnostic ability of transabdominal imaging, so these patients may be better served with transvaginal imaging. Patients with vaginal trauma may have difficulties with the transvaginal approach due to pain. Another consideration is the patient's age. Younger patients may not have had pelvic examinations previously, and transvaginal ultrasonography may provoke anxiety in these patients. It may be reasonable to start with transabdominal imaging and use transvaginal imaging as a second-line alternative.[3]

Equipment

Transabdominal imaging is classically completed using a curvilinear probe in an obstetrical examination mode. A standard stretcher is appropriate for this examination mode as the patient will be lying supine. Transvaginal imaging requires an endocavitary probe and a probe cover, usually a condom. The gel is needed inside the condom, and sterile water gel is needed outside of the condom. This probe is usually higher frequency than the transabdominal probe, allowing for higher resolution at the shallow depths that are used from the transvaginal approach. An obstetrical stretcher with stirrups is the ideal stretcher for patient positioning. Alternatively, the patient may be placed on a pelvic pillow, allowing the pelvis to be elevated off the bed and for the probe handle to be angled below the level of the patient's buttocks.

Personnel

The initial ultrasound images may be performed at the bedside when evaluating for intrauterine versus ectopic pregnancy. This is especially important in a hemodynamically unstable patient where obstetrical services for immediate consultation may not be available. Emergency physicians have been trained primarily and transabdominal ultrasonography, though there is a growing movement toward increasing training for transvaginal ultrasonography as well. The diagnosis may be made at this initial exam, but many times the examination is indeterminate. Out of these cases, the literature suggests that there are poor fetal and maternal outcomes, clearly indicating the need for formal diagnostic imaging by trained ultrasonography technicians in these patients.

Preparation

The transabdominal examination is best performed with a curvilinear probe but may be performed using a phased array probe (see Video. Ectopic Pregnancy Gestation Sac, Ultrasound). To best evaluate the patient in the transabdominal views, the patient must be well hydrated and have a full bladder, creating an acoustic window. Intravenous fluids, oral hydration, or Foley catheter fluid insertion are appropriate methods for hydration, depending on the urgency of the workup. Posterior enhancement, the artifact created when acoustic waves pass through a fluid-filled structure, may make it difficult to visualize the far field of the image. It may be difficult to adjust the gain enough to correct this. The patient should be placed in a gown and sheets should be available to minimize exposure of the patient during evaluation.

In contrast to transabdominal preparation, transvaginal examination requires the patient to have an empty bladder. The patient is best able to be examined if she is positioned in stirrups on an obstetrical stretcher. A pelvic pillow is an alternative that allows the pelvis to be lifted off a standard stretcher. The probe should then be prepared for optimal acoustic transmission and maximal patient safety. This is done using a probe cover, typically a latex condom or synthetic alternative, with gel on the probe head beneath the condom. Any air bubbles need to be pressed off the probe head, as air will impede the ultrasound waves. Sterile, water-soluble lubricant should be used on the exterior of the condom as there is a theoretical risk of infection from ultrasound gel, and some women find the gel irritating. The depth will likely require adjustment to optimize the visual field.

Technique or Treatment

Obstetrical examination mode minimizes radiation exposure and should be used for all obstetric evaluation in accordance with the "as low as (is) reasonably achievable" (ALARA) practice standard. The base technique for both the transabdominal and transvaginal evaluation for ectopic pregnancy is the routine obstetric evaluation, as identifying a live intrauterine pregnancy greatly decreases the chances of an ectopic pregnancy being present, as previously discussed.

Transabdominal Examination

The transabdominal view is obtained with the patient in a supine position on a stretcher with a full bladder. The probe is placed in the longitudinal plane (indicator towards the head of the patient) in the midline above the symphysis pubis. If the probe is placed too far from the cephalad, the bladder will not be able to be optimally used as an acoustic window, and bowel gas may obstruct the view. The bladder and uterus should be identified. Probe position and depth should be adjusted to center the uterus in the visual field. An adequate view of the uterus will have the length of the uterus on the screen, with the cervix and part of the vagina being visualized. The endometrial stripe is a hyperechoic structure in the center of the uterus. Caution should be taken when identifying fluid surrounding the suspected pregnancy. If this is the focus of the examination instead of the endometrial stripe, an ectopic pregnancy may be mistaken as an intrauterine pregnancy. In the longitudinal view, the endometrial stripe and uterus will have elongated appearances. When switching to the transverse view, the uterus will be circular. While in the transverse view, the entire length of the uterus needs to be swept through, paying attention to the uterine tissue as well as the area around the uterus. This is the most difficult step as it is difficult to avoid bowel gas and follow the uterus through the entire length of the sweep.

The bladder will be at the top of the screen, and the uterus will be a round structure just far field to the bladder. The distal portion of the field of the uterus needs to be centered on the screen so the entire area around the uterus can be visualized. A common mistake is incorrectly identified in the vagina as the uterus. To distinguish this, it is important to recognize that the endometrial stripe, while in the transverse view, will be a dot or oval, while the vaginal stripe will appear to be a line going across the screen. If the uterus is anteverted, both the vagina and the uterus may be visualized in the same image. To ensure that uterine tissue is being visualized, use the bladder as a landmark, as this should be immediately adjacent to the uterus. This is one advantage of the abdominal approach, as the bladder is more easily visualized, and any masses between the bladder and uterus should be clearer than with the transvaginal view. Free fluid between the bladder and uterus, a mass between the bladder and uterus, or free fluid anywhere around the uterus is a concerning finding for possible ectopic pregnancy in the transabdominal views. Masses posterior to the uterus may be more difficult to identify. If an intrauterine pregnancy is identified in the transabdominal view in a patient with a low index of suspicion for heterotopic pregnancy, the transvaginal views may not be necessary unless further diagnostic workup is desired for the pregnancy.[3]

Transvaginal Examination

The initial approach is with the probe in the sagittal plane, with the indicator pointed towards the ceiling. There should be a tactile indicator on the handle of the probe to assist in the orientation of the ultrasound. The probe should be inserted approximately 4 to 5 centimeters. The first step during the transvaginal examination is identifying the bladder and, subsequently, the juxtaposition between the bladder and the uterus. Confirming this juxtaposition is a critical step, as it makes it much less likely that the examination is being performed in the adnexa. To identify the bladder, the handle should be moved towards the stretcher, thereby directing the probe head towards the ceiling. The opposing handle and probe head directions of movement make this a more difficult exam to maintain spatial awareness. The area of interest of the examination will be the uterine tissue in the endometrial stripe in the center. In the sagittal view, with the indicator towards the ceiling, the uterus will be oblong, and the endometrial stripe will be a line.

Similar to the transabdominal view, the uterus needs to be centered on the screen so the fundus and the surrounding tissue are not excluded from the field of view. When the uterus is centered, a side-to-side sweep is performed in the sagittal plane. This should be done slowly to visualize the entire uterus adequately. This needs to be done until the uterus completely disappears from the screen in each direction. After this, the probe will be rotated 90 degrees with the indicator pointing towards the patient's right in a coronal plane. The length of the uterus should be swept through again, this time with the probe handle moving up and down rather than right and left. If there is no intrauterine pregnancy identified in a pregnant patient with a beta hCG greater than 2000, the patient should be considered to have an ectopic pregnancy until proven otherwise. Signs of free fluid around the uterus, masses between the uterus and the bladder, masses in the adnexa, or an identifiable pregnancy outside of the uterus are concerning or diagnostic of an ectopic pregnancy.

Clinical Significance

The clinical impact of diagnosis timely diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy cannot be understated. There are significant morbidity and mortality associated with ectopic pregnancy, and early diagnosis can have a significant impact in reducing both of these. As previously mentioned, there is a role for bedside performance of these examinations, and this should be part of the standard emergency physician and obstetrician training. After completing the ultrasounds, whether bedside or elective imaging, the images should be reviewed in detail as there are many signs of potential ectopic pregnancy to identify. The most reliable sign of ectopic pregnancy is the visualization of extrauterine gestation. However, this is found in the minority of ectopic pregnancies. A key concept to reiterate is the use of beta hCG levels when reviewing ultrasonography images. The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy should be considered with elevated beta hCG levels with the absence of an intrauterine pregnancy on ultrasound. The discriminatory zone is the titer of hCG, where an intrauterine sac should be seen with transvaginal ultrasonography and normal pregnancy.

There are varying standards for discriminatory zones, but 1500 to 2000 mIU/mL of hCG has been accepted in the past.[6][7] If there is a practice standard for your institution, that should be taken into account. However, caution should also be exercised with using the discriminatory zone, as emergency department patients with hCG levels lower than 1500 mIU/mL have been shown to have a two-fold risk increase for ectopic pregnancy. The discriminatory zone also does not take into account the possibility of multiple gestations, where the intrauterine sac or sacs may still be too small to visualize despite higher levels of beta hCG. There are findings on ultrasound that are indicative of possible ectopic pregnancy. Positive findings include an empty uterine cavity, a decidual cast, a thick echogenic endometrium, or a pseudo-gestational sac in the presence of beta hCG levels above the discriminatory zone.[6] In the peritoneal cavity, free pelvic fluid or hemoperitoneum in the pouch of Douglas in the presence of a positive beta hCG is 70% specific for ectopic pregnancy and 63% sensitive. A live pregnancy identified in the peritoneal cavity is 100% specific but is rarely identified.

In the adnexal area, viewing the fallopian tubes and ovaries, there are multiple signs consistent with potential ectopic pregnancies. Simple adnexal cysts and the presence of positive beta hCG levels have approximately a 10% chance of being an ectopic pregnancy. A complex extra adnexal cyst or mass has a 95% chance of being a tubal ectopic if there is no intrauterine pregnancy identified. If this is within the adnexa, it is much more likely to be a corpus luteum ectopic pregnancy. Any solid mass in the adnexa may be ectopic but is not specific. A tubal ring sign is a sign of a tubal ectopic in which there is an echogenic ring surrounding a likely unruptured ectopic pregnancy, with a reported 95% positive predictive value.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of an ectopic pregnancy is made by an interprofessional team that includes the emergency department physician, radiologist, obstetrician, and nurse practitioner. No patient should be discharged home if an ectopic is suspected. Ectopic pregnancies are a common gynecologic emergency that typically impacts otherwise healthy individuals and can have significant morbidity and mortality. Continued improvement in the ultrasonographic evaluation of these patients will aid in decreasing the mortality that continues to be associated with ruptured ectopic pregnancies.[8][9][10]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The initial action that is needed by the nurse at the time of patient presentation when there is a possibility of an ectopic pregnancy is to establish the patient safety net, consisting of obtaining a full set of vital signs, placing the patient on the monitor, and obtaining at least 1 large bore intravenous line. If the local nursing scope of practice includes drawing blood for labs, that will be needed as well for these patients. If the patient is stable, the next nursing action will be to hydrate the patient. The transabdominal portion of the ultrasound assessment is best performed with a full bladder. Oral hydration is able to help with this, but intravenous fluid administration is another option, depending on whether the patient is being allowed to take anything orally at that time. It is important to coordinate the hydration status with the provider performing the ultrasound, as it can be very uncomfortable for the patient if she is required to hold a full bladder for an extended time. After the diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy is established, it will be important for the nurse to be a patient advocate. The patient should be given mental support, and institutions may have support systems in place for mothers who have been diagnosed with a nonviable pregnancy.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Any patient with a suspected ectopic pregnancy needs to have a full set of vital signs on the initial presentation. Frequent reassessments of the blood pressure and heart rate are important to clue the team toward the development of shock from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

Media

(Click Video to Play)

Ectopic Pregnancy Gestation Sac, Ultrasound. This image of a transabdominal probe shows a gestational sac and fetal pole, not within the uterus.

Contributed by A Kurzweil, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Levine D. Ectopic pregnancy. Radiology. 2007 Nov:245(2):385-97 [PubMed PMID: 17940301]

Padilla LA, Radosevich DM, Milad MP. Accuracy of the pelvic examination in detecting adnexal masses. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2000 Oct:96(4):593-8 [PubMed PMID: 11004365]

Kaakaji Y, Nghiem HV, Nodell C, Winter TC. Sonography of obstetric and gynecologic emergencies: Part II, Gynecologic emergencies. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2000 Mar:174(3):651-6 [PubMed PMID: 10701603]

Juliano ML, Sauter BM. Fetal outcomes in first trimester pregnancies with an indeterminate ultrasound. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2012 Sep:43(3):417-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.021. Epub 2011 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 21719231]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDaniilidis A, Pantelis A, Makris V, Balaouras D, Vrachnis N. A unique case of ruptured ectopic pregnancy in a patient with negative preg-nancy test - a case report and brief review of the literature. Hippokratia. 2014 Jul-Sep:18(3):282-4 [PubMed PMID: 25694767]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKadar N, Bohrer M, Kemmann E, Shelden R. The discriminatory human chorionic gonadotropin zone for endovaginal sonography: a prospective, randomized study. Fertility and sterility. 1994 Jun:61(6):1016-20 [PubMed PMID: 8194610]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKohn MA, Kerr K, Malkevich D, O'Neil N, Kerr MJ, Kaplan BC. Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin levels and the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy in emergency department patients with abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003 Feb:10(2):119-26 [PubMed PMID: 12574008]

Beals T, Naraghi L, Grossestreuer A, Schafer J, Balk D, Hoffmann B. Point of care ultrasound is associated with decreased ED length of stay for symptomatic early pregnancy. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2019 Jun:37(6):1165-1168. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.03.025. Epub 2019 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 30948256]

Wang PS, Rodgers SK, Horrow MM. Ultrasound of the First Trimester. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2019 May:57(3):617-633. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2019.01.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30928081]

Mukherjee R, Samanta S. Surgical emergencies in pregnancy in the era of modern diagnostics and treatment. Taiwanese journal of obstetrics & gynecology. 2019 Mar:58(2):177-182. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2019.01.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30910134]