Introduction

Tarlov cysts are perineural cysts between the perineurium and endoneurium, arising near the dorsal root ganglion.[1] They can occur anywhere in the spine but most frequently around the sacral nerve roots, with S2 being the most common level.[2] The cysts are usually filled with cerebrospinal fluid but may contain blood if there is a hemorrhagic complication.[3][4] They are mostly asymptomatic but can present as chronic back pain in the sacral or coccyx area and may have radiculopathy or red flag features such as leg weakness, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and sexual dysfunction.[5] The features may also be acute, especially if cyst complications like rupture or hemorrhage occur.

It was originally described on autopsy findings in 1938 by American neurosurgeon Dr. Isadore Tarlov.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The exact cause of Tarlov cysts remains unknown. But the cyst is difficult to shrink on its own accord and may grow due to the flow of cerebrospinal fluid into the cyst through a one-way valve system.[6] There is circular scarring of the arachnoid mater around the introitus of the cyst, which forms a valve. This is the target for surgical therapy in some techniques to restore the normal flow of CSF and promote regression.

There is an association with collagen disorders such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.[7][8]

Epidemiology

Overall, Tarlov cysts are rare. The most recent published meta-analysis suggests a global prevalence rate of 4.27%; in the United States, it is 3.82% of the population. Tarlov cysts are more common in those of the female sex (female 7.01% vs. male 4.05%). The same study also showed that 15.59% of the cysts are symptomatic.[2]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiological process is not understood well.

Dr. Tarlov's original theory is that due to trauma and hemorrhage, this causes hemosiderin deposition and a blockage of venous drainage in the perineurium and epineurium, leading to cystic degeneration.

Another theory is that genetic risk factors that increase congenital arachnoidal proliferation along with the exiting sacral nerve roots promote the development of the cystic structures.

The cysts themselves are connected to the subarachnoid space, and the leading theory in the growth of cysts is due to a one-way valve mechanism. The pulsatile flow of the CSF allows the cyst to expand but not reduce in size, and it is thought that this explains why only some Tarlov cysts are symptomatic and worsen with time. The growth and pressure that it exerts on adjacent nerve fibers result in neurological symptoms, but it may also erode the surrounding sacral bone and irritate the periosteum, which may also result in pain.[5]

Histopathology

By definition, they would require a nerve root or its fibers in the cyst's wall or cavity.

The cystic lesion under histopathological examination has fibrotic changes, and fibro-collagenous and membraneous connective tissue is the most common finding. Hemorrhage may occur and, as a result, invite an inflammatory process, and macrophages and hemosiderin deposits can be seen. An extensive inflammatory component is rarely observed.[9]

The cysts may be uni-loculated or multi-loculated.

History and Physical

History

Most patients describe a history of chronic or acute-on-chronic back pain, which may be radicular with dermatomal pain, reduced sensation, or weakness.

A study by Hulens et al. has shown that symptomatic Tarlov cysts present more frequently with perineal pain/discomfort, bladder and bowel disturbance, and sexual disturbance (dyspareunia, impotence). They found that patients are more likely to report that their pain worsens with activity (neurogenic claudication), Valsalva maneuvers, and sitting.[10] This may then cause the patients to miss work or social activities.

Other details to cover in the history include trauma, signs, and symptoms of infection, and malignancy.

Examination

A detailed neurological examination should be performed on symptomatic areas.

The dermatomes and myotomes of the lower limbs and perineum, as well reflexes of the lower limbs, and if there are features of urinary retention and anal sphincter tone.

As it is a lower motor neuron lesion, it may result in reduced reflexes and anal tone in addition to sensory loss or motor weakness.[11]

Evaluation

The evaluation is dependent on the healthcare context in which the patient is seen. In general practice or emergency department, the main consideration would be cauda equina syndrome, which may be caused by a large Tarlov cyst.[12] Hence, if cauda equina syndrome is suspected, referral to the local spinal service would be necessary.

As cauda equina syndrome or compression presents a spectrum with varying symptomatology, this is the main diagnosis to exclude, and evaluation is tailored in this manner.[13] The gold standard to achieve this would be a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the lumbosacral spine. In cases where MRI is contra-indicated, CT myelography would be an alternative but more invasive.

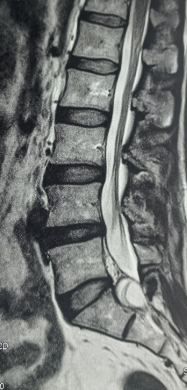

MRI is currently the preferred imaging modality to evaluate Tarlov cysts. They appear as thin-walled cystic structures that are closely related to nerves. The cyst itself is extra-dural and contains the nerve root within its walls, and is classified as a type 2 spinal meningeal cyst by Nabor et al.[14]

The cyst should appear as a low signal on T1 and a high signal (equivalent to CSF) on T2.[15] Its morphology can vary from simple to complex cysts with loculations and septations. The sacral foramina may be widened.

Treatment / Management

Treatment can be divided into conservative, medical and invasive therapies, which can be further subdivided into percutaneous or open surgical techniques.

Conservative and Medical Treatment

Conservative treatment is the preferred option for asymptomatic, incidentally picked up Tarlov cysts.

Medical therapy is generally analgesics, such as paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), opiates, anti-depressants such as amitriptyline, and anticonvulsants such as pregabalin and gabapentin.[16](B3)

Caudal epidural steroid injections have been described as a treatment with good effect for patients with bladder pain syndrome type symptoms and incidental Tarlov cysts.[17] However, its use is not widespread.(B3)

Percutaneous Therapies

The cyst can be aspirated, or through a newer two-needle technique, the cyst can be aspirated and injected with fibrin glue to reduce the dead space and reaccumulation of CSF.

The aspiration-injection technique will have a needle deep in the cyst and a superficial second needle to allow fluid to be aspirated from the deep needle and allow air to enter through the superficial needle.

The air-fluid level that develops can be monitored using CT fluoroscopy, or alternative, an iodinated contrast agent that would allow visualization through an image intensifier. However, the agent would fill up and reduce the effectiveness of the injected fibrin glue.

Once communication with the thecal sac is established by rapid refilling of the cyst, a fibrin glue such as Tisseel is used to plug the cyst.[18]

Open Surgical Techniques

Microsurgical

This option includes cyst excision or fenestration with subsequent imbrication and dural repair. The repair is often then covered with a patch and/or Tisseal to reduce the incidence of CSF leak.[19] The nerve root is often left intact, but excision of the nerve root has been described as a possibility; however, it is not popular in literature.[20]There are newer techniques described, such as occlusion of introitus and communicating channels with muscle graft, and puckering of cyst after fenestration to reduce reaccumulation of CSF.[21][22]Radical Techniques(B2)

Decompressive laminectomy is less often practiced, but single-level laminectomies can be offered. A keystone article identified that 7 out of 10 patients that received treatment had complete or substantial resolution with follow-up on average of over two years. The authors noted that cysts above 1.5cm correlated with better outcomes, but this has been shown to not be statistically significant in meta-analysis in recent publications.[23][24] However, cyst size was not commonly reported.(A1)

Shunting - This can include lumbo-peritoneal or cyst-subarachnoid shunts.

Complications of Invasive Treatment

Surgery is associated with higher complication rates compared to percutaneous procedures.

Specific complications include

Differential Diagnosis

If the presentation is chronic back pain, considerations range from mechanical back pain to cauda equina compression and spine infection such as discitis or malignancy.[25]

Radiologically, the diagnosis itself is usually straightforward, and no other differentials are entertained. However, in borderline cases on imaging, differentials would include the following:

Prognosis

For treated Tarlov cysts, symptom relief is generally good and does not appear to significantly differ initially between surgical treatment over percutaneous treatment. However, the recurrence rates are lower in surgically treated cysts compared to percutaneously treated cysts (8% over 20%). This may be limited by the length of follow-up as surgically managed patients are, on average, followed up for longer compared to percutaneously treated ones (38 months vs. 15 months).[29]

In terms of symptom relief, it is reported that 81% of patients treated surgically remain symptom-free at one year, similar to the cyst being completely or substantially reduced in size (79%).[24]

Complications

Complications are generally cyst wall rupture and hemorrhage into the cyst, both of which are rare. This may intensify pre-existing or produce new symptoms such as radiculopathy or even mimicking cauda equina syndrome.[30][31] Bleeding from an intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage has also been reported to track into the Tarlov cyst and produce similar symptoms.[32]

In perhaps exceedingly rare circumstances, a sacral fracture following trauma may leak intra-medullary contents through a Tarlov cyst and produce acute cerebral fat embolism.[33]

The appearance of a hemorrhage within a Tarlov cyst may re-present features of intradural carcinomatosis, which may lead to unnecessary investigations and management for the patient.[34]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The reasons for symptoms require careful exploration to manage the patient's expectations and clinical outcomes. It must be stressed that Tarlov cysts may not be the sole cause of symptoms, and evaluation should attempt to look for other causes of symptoms.[35] Once all possible causes are found, then careful consultation, including the risks, benefits, and recurrence of cyst or symptoms, should be explained to the patient. An interprofessional team approach should be used to improve patient outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Tarlov cysts are often overlooked due to several factors. This can lie with the physician or radiologist responsible for interpreting the imaging, as Tarlov cysts are considered clinically irrelevant, and other degenerative spine conditions are usually blamed as the reason for the patient's symptoms. It is also difficult to use an objective measure to ascertain that Tarlov cysts are the reason for symptoms. And when imaging or electromyography is used to try to confirm, they are often limited to L1 - S1 nerve roots.[36]

Treatment is therefore also controversial, but methods to treat exist. Careful selection of levels and reasons for symptoms is crucial to maximizing treatment effectiveness. Recurrence of cysts and symptoms may occur despite initial effective treatment and must be highlighted to manage patient expectations. This, therefore, would require an interprofessional team approach - usually comprising of a pain specialist, spinal surgeon, specialist nurses, family medicine doctor (including PAs and NPs), and the patient.

Media

References

Chaiyabud P, Suwanpratheep K. Symptomatic Tarlov cyst: report and review. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet. 2006 Jul:89(7):1047-50 [PubMed PMID: 16881441]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKlepinowski T, Orbik W, Sagan L. Global incidence of spinal perineural Tarlov's cysts and their morphological characteristics: a meta-analysis of 13,266 subjects. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2021 Jun:43(6):855-863. doi: 10.1007/s00276-020-02644-y. Epub 2021 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 33452905]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFletcher-Sandersjöö A, Mirza S, Burström G, Pedersen K, Kuntze Söderqvist Å, Grane P, Fagerlund M, Edström E, Elmi-Terander A. Management of perineural (Tarlov) cysts: a population-based cohort study and algorithm for the selection of surgical candidates. Acta neurochirurgica. 2019 Sep:161(9):1909-1915. doi: 10.1007/s00701-019-04000-5. Epub 2019 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 31270612]

Soon WC, Sun R, Czyz M. Haemorrhagic Tarlov cyst: A rare complication of anticoagulation therapy. Oxford medical case reports. 2021 Aug:2021(8):omab063. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omab063. Epub 2021 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 34408886]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLucantoni C, Than KD, Wang AC, Valdivia-Valdivia JM, Maher CO, La Marca F, Park P. Tarlov cysts: a controversial lesion of the sacral spine. Neurosurgical focus. 2011 Dec:31(6):E14. doi: 10.3171/2011.9.FOCUS11221. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22133181]

Yoshioka F, Shimokawa S, Masuoka J, Inoue K, Ogata A, Abe T. Elimination of the check-valve mechanism of the sacral Tarlov cyst using a rotation flap technique in a pediatric patient: technical note. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2021 May:37(5):1741-1745. doi: 10.1007/s00381-020-05029-z. Epub 2021 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 33404709]

Isono M, Hori S, Konishi Y, Kinjo H, Kakisako K, Hirose R, Yoshida T. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome associated with multiple spinal meningeal cysts--case report. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 1999 May:39(5):380-3 [PubMed PMID: 10481443]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDoi H, Sakurai S, Ida M, Sora S, Asamoto S, Sugiyama H. [A case of sacral meningeal cyst with Marfan syndrome]. No shinkei geka. Neurological surgery. 1999 Sep:27(9):847-50 [PubMed PMID: 10478347]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNeulen A, Kantelhardt SR, Pilgram-Pastor SM, Metz I, Rohde V, Giese A. Microsurgical fenestration of perineural cysts to the thecal sac at the level of the distal dural sleeve. Acta neurochirurgica. 2011 Jul:153(7):1427-34; discussion 1434. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1043-0. Epub 2011 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 21562735]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHulens MA, Dankaerts W, Rasschaert R, Bruyninckx F, Willaert ML, Vereecke C, Vansant G. Can patients with symptomatic Tarlov cysts be differentiated from patients with specific low back pain based on comprehensive history taking? Acta neurochirurgica. 2018 Apr:160(4):839-844. doi: 10.1007/s00701-018-3494-z. Epub 2018 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 29455410]

Shahrokhi M, Asuncion RMD. Neurologic Exam. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491521]

Nicpoń KW, Lasek W, Chyczewska A. [Cauda equina syndrome caused by Tarlov's cysts--case report]. Neurologia i neurochirurgia polska. 2002 Jan-Feb:36(1):181-9 [PubMed PMID: 12053609]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGardner A, Gardner E, Morley T. Cauda equina syndrome: a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2011 May:20(5):690-7. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1668-3. Epub 2010 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 21193933]

Nabors MW, Pait TG, Byrd EB, Karim NO, Davis DO, Kobrine AI, Rizzoli HV. Updated assessment and current classification of spinal meningeal cysts. Journal of neurosurgery. 1988 Mar:68(3):366-77 [PubMed PMID: 3343608]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim K, Chun SW, Chung SG. A case of symptomatic cervical perineural (Tarlov) cyst: clinical manifestation and management. Skeletal radiology. 2012 Jan:41(1):97-101. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1243-y. Epub 2011 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 21830055]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJain M, Sahu NK, Naik S, Bag ND. Symptomatic Tarlov cyst in cervical spine. BMJ case reports. 2018 Dec 4:11(1):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-228051. Epub 2018 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 30567194]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFreidenstein J,Aldrete JA,Ness T, Minimally invasive interventional therapy for Tarlov cysts causing symptoms of interstitial cystitis. Pain physician. 2012 Mar-Apr; [PubMed PMID: 22430651]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMurphy K, Oaklander AL, Elias G, Kathuria S, Long DM. Treatment of 213 Patients with Symptomatic Tarlov Cysts by CT-Guided Percutaneous Injection of Fibrin Sealant. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2016 Feb:37(2):373-9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4517. Epub 2015 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 26405086]

Medani K, Lawandy S, Schrot R, Binongo JN, Kim KD, Panchal RR. Surgical management of symptomatic Tarlov cysts: cyst fenestration and nerve root imbrication-a single institutional experience. Journal of spine surgery (Hong Kong). 2019 Dec:5(4):496-503. doi: 10.21037/jss.2019.11.11. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32043000]

Sun JJ, Wang ZY, Teo M, Li ZD, Wu HB, Yen RY, Zheng M, Chang Q, Yisha Liu I. Comparative outcomes of the two types of sacral extradural spinal meningeal cysts using different operation methods: a prospective clinical study. PloS one. 2013:8(12):e83964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083964. Epub 2013 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 24386317]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYang K, Tao H, Feng C, Xu J, Duan C, Yang W, Su W, Li H, Li H. Surgical management of sacral meningeal cysts by obstructing the communicating holes with muscle graft. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2019 Dec 30:20(1):635. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2998-x. Epub 2019 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 31888578]

Yucesoy K, Yilmaz M, Kaptan H, Ikizoglu E, Arslan M, Erbayraktar SR. A novel surgical technique for treatment of symptomatic Tarlov cysts. British journal of neurosurgery. 2023 Apr:37(2):188-192. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2021.2016623. Epub 2021 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 34931571]

Voyadzis JM,Bhargava P,Henderson FC, Tarlov cysts: a study of 10 cases with review of the literature. Journal of neurosurgery. 2001 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 11453427]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKameda-Smith MM, Fathalla Z, Ibrahim N, Astaneh B, Farrokhyar F. A systematic review of the efficacy of surgical intervention in the management of symptomatic Tarlov cysts: a meta-analysis. British journal of neurosurgery. 2024 Feb:38(1):49-60. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2021.1874294. Epub 2021 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 33754918]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDePalma MG. Red flags of low back pain. JAAPA : official journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2020 Aug:33(8):8-11. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000684112.91641.4c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32740106]

Foran JR, Pyeritz RE, Dietz HC, Sponseller PD. Characterization of the symptoms associated with dural ectasia in the Marfan patient. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2005 Apr 1:134A(1):58-65 [PubMed PMID: 15690402]

Attiah MA, Syre PP, Pierce J, Belyaeva E, Welch WC. Giant cystic sacral schwannoma mimicking tarlov cyst: a case report. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2016 May:25 Suppl 1():84-8. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4128-2. Epub 2015 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 26195080]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBansal S, Suri A, Sharma MC, Kakkar A. Isolated lumbar intradural extra medullary spinal cysticercosis simulating tarlov cyst. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2017 Apr-Jun:12(2):279-282. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.150225. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28484552]

Sharma M, SirDeshpande P, Ugiliweneza B, Dietz N, Boakye M. A systematic comparative outcome analysis of surgical versus percutaneous techniques in the management of symptomatic sacral perineural (Tarlov) cysts: a meta-analysis. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2019 Feb 8:():1-12. doi: 10.3171/2018.10.SPINE18952. Epub 2019 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 30738394]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGodel T, Pham M, Wolff M, Bendszus M, Bäumer P. Tarlov Cyst Hemorrhage Causing Acute Radiculopathy: A Case Report. Clinical neuroradiology. 2018 Mar:28(1):123-125. doi: 10.1007/s00062-017-0597-5. Epub 2017 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 28523386]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYates JR, Jones CS, Stokes OM, Hutton M. Incomplete cauda equina syndrome secondary to haemorrhage within a Tarlov cyst. BMJ case reports. 2017 Aug 7:2017():. pii: bcr-2017-219890. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-219890. Epub 2017 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 28784878]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKong WK, Cho KT, Hong SK. Symptomatic tarlov cyst following spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2011 Aug:50(2):123-5. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2011.50.2.123. Epub 2011 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 22053232]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDuja CM, Berna C, Kremer S, Géronimus C, Kopferschmitt J, Bilbault P. Confusion after spine injury: cerebral fat embolism after traumatic rupture of a Tarlov cyst: case report. BMC emergency medicine. 2010 Aug 15:10():18. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-10-18. Epub 2010 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 20712856]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSudhakar T, Désir LL, Ellis JA. Tarlov Cyst Rupture and Intradural Hemorrhage Mimicking Intraspinal Carcinomatosis. Cureus. 2021 Jun:13(6):e15423. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15423. Epub 2021 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 34249569]

Beynon R, Elwenspoek MMC, Sheppard A, Higgins JN, Kolias AG, Laing RJ, Whiting P, Hollingworth W. The utility of diagnostic selective nerve root blocks in the management of patients with lumbar radiculopathy: a systematic review. BMJ open. 2019 Apr 20:9(4):e025790. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025790. Epub 2019 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 31005925]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHulens M, Rasschaert R, Bruyninckx F, Dankaerts W, Stalmans I, De Mulder P, Vansant G. Symptomatic Tarlov cysts are often overlooked: ten reasons why-a narrative review. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2019 Oct:28(10):2237-2248. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-05996-1. Epub 2019 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 31079249]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence