Introduction

Neutropenic enterocolitis (NE) has been a life-threatening condition with a mortality rate of 30% to 50%.[1] It is also known as typhlitis, from the Greek typhi or “blind” in reference to the blind-ending cecum, which describes neutropenic enterocolitis of the cecum that affects the ileal region as well and can spread to the ascending colon.[2][3] Neutropenic enterocolitis is characterized by bowel wall edema, ulceration, and hemorrhage, and it mainly occurs in immunosuppressed patients.[4] Although poorly understood, NE appears to be the result of intestinal mucosal injury in the setting of neutropenia that can be due to treatment with cytotoxic chemotherapy, radiation, or leukemic infiltration.[5] NE is recognized as a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality in immunosuppressed patients. Therefore, a high index of suspicion and early diagnosis is eminent. In this article, we assess recent concepts about the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of neutropenic enterocolitis.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The pathogenesis of neutropenic enterocolitis is incompletely defined. Between the diverse components of the disease onset, we find that an intestinal mucosal injury, a neutropenic state, and the immunocompromised status of the patients are the most important elements. The combination of all these factors can lead to intestinal edema, blood vessels dilation, and tearing of the mucosal surface. The last will be an essential element for further bacterial intramural invasion.[6]

Despite having a damaged mucosa in the setting of a neutropenic patient, a superimposed infection on these patients is not always considered a diagnostic criterion. It is well known the infection takes part in the pathogenesis of NE, and different organisms have been reported.[7] Among these, we find Gram-negative rods, gram-positive cocci, enterococci, fungi, and viruses.[8] Sloas et al. detailed their study in children where NE was identified in 24 children with leukemia.[9] They revealed six different pathogens in eight patients with bacteremia (Escherichia coli in 3 patients, Klebsiella pneumoniae in 2 patients, Enterobacter taylorae, Morganella morganii, and a Streptococcus viridans in 1 patient each).

Other organisms, such as fungal pathogens, can have an important role in NE. This has been demonstrated in patients that undergo antifungal therapy and have better outcomes compared to those who not. For example, a systematic review of published case studies found a substantially lower mortality rate in treatments that include antifungal agents for the treatment of NE.[10]

Epidemiology

The real incidence of neutropenic enterocolitis differs considerably from 0.8% to 26% likely because of the heterogeneous presentation of neutropenic enterocolitis and the variability of the age groups covered in different studies.[11][12] Initial reports were based primarily on autopsy studies of leukemia and lymphoma patients, with mortality rates mostly due to transmural bowel necrosis, perforation, and sepsis.

On the one hand, in children, incidence rates up to 46% on autopsies were reported associated with their pathologic condition.[13] On the other hand, a pooled incidence of 5.6% in hospitalized adults with hematological malignancies, chemotherapy for solid tumors, and aplastic anemia; was reported in a systematic review published in 2005.[7] These extended ranges on incidence exist in part due to significant variations of diagnostic criteria.

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism and pathophysiology behind neutropenic enterocolitis are still unclear, though there are several proposed theories. It is commonly thought that neutropenia leads to reduced mucosal protection. This drives to a bacterial invasion of the colonic wall, consequently causing necrosis and perforation. NE almost always affects the cecum, therefore sometimes it is called “typhlitis,” but involvement can spread to other parts of the colon as well.[11] The ileocecum is presumably most vulnerable to NE based on abundant lymphoid tissue, increased stasis and ability to distend, and decreased vascularity.[12]

Further associations for the singular relation between reduced mucosal protection and bacterial invasion involve specific chemotherapeutic regimens, shifts in the bowel flora, and other cytokine-driven processes. Since NE was primarily observed and described in patients with hematologic malignancies under antineoplastic therapy, studies determined that some of the most common chemotherapeutic agents associated are cytosine arabinoside, etoposide corticosteroids, and taxane-based agents.[12]

The different chemotherapeutic agents have been associated with producing a direct mucosal injury (mucositis), thereby creating an environment that predisposes distension and necrosis and, as a consequence, a change in the intestinal peristalsis.[5] The destruction of the normal mucosa structure can be an effect of radiotherapy, the possible coexisting leukemic or lymphomatous infiltrate, or the intramural hemorrhage due to severe thrombocytopenia.[13]

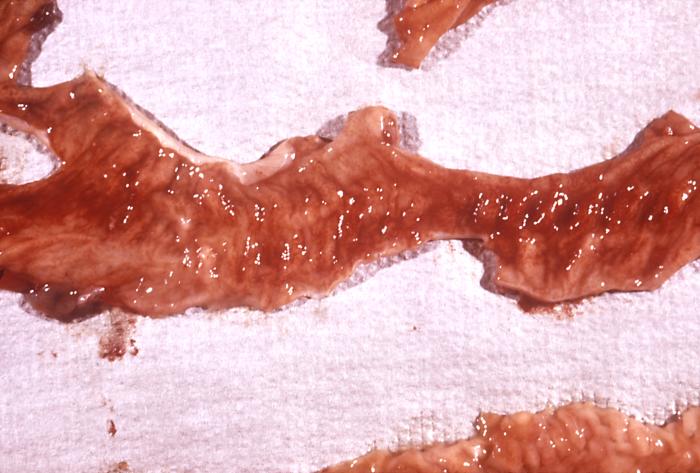

Histopathology

The nearly whole gut can be compromised in neutropenic enterocolitis, but most commonly involved areas are from terminal ileum to the ascending colon. There are many important histopathologic aspects, while the most characteristics features in any region are acute hemorrhagic necrosis, ulceration of the mucosa wall, widespread edema involving the submucosa, and lamina propria, prominent vessel congestion, and a deep mural and transmural necrosis.[12] Most importantly, a significant infiltrative inflammation should be absent in NE due to the profound neutropenia. During the histologic examination, many different organisms, such as bacterias or fungus hyphae, were identified. This environment of organism overgrowth would ensure an inflammatory cell infiltration, even though this response is characteristically absent.

Between other potential factors involved in the pathogenesis of NE, we can find the intestinal leukemic infiltration, this feature may explain the acute myelogenous leukemia manifesting as NE in patients undergoing chemotherapy therapy. Perhaps, some studies have not reported this leukemic infiltration after histologic evaluation. Other histologic findings have included mucosal ulcers and intramural hemorrhage, usually associated with thrombocytopenia.

Even though all these characteristics are important, histopathology is not included as a current diagnostic criterion.

History and Physical

The classic clinical scenario of typhlitis is a patient with neutropenia and fever following intensive chemotherapy, usually will present abdominal pain that will follow after two weeks of chemotherapy. As well, other manifestations involve abdominal distention (reported in 66% of patients), anorexia, nausea, diarrhea (with or without blood), and rebound tenderness. But these symptoms are blunt since it is a condition occurring in patients with immunosuppression and/or severe neutropenia, or these symptoms may be minimal and evolve.

As well, fever is common in the majority of patients.[7] Nonetheless, fever may occasionally be absent, particularly in severely immunocompromised patients and those under therapy with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents.

During the physical examination, tenderness can be found on palpation, and this abdominal pain can be localized in the lower right quadrant or can be more diffuse. Abdominal compartment syndrome has been reported in patients with NE presenting with abdominal distension and ascites. Melena or hematochezia are generally less common forms of presentation. Peritoneal signs, shock, abdominal distention, and rapid clinical deterioration can be suggestive of necrosis and a bowel perforation.

Evaluation

Determining a diagnosis of neutropenic enterocolitis has been considerably challenging, even unclear. This due to a nonclear definition of the syndrome, as well as of a need for specific diagnostic criteria. With the wide availability of CT and a growing body of information on the disease and its radiographic features, more precise and standardized diagnostic criteria have been established.

Although some experts may differ in diagnostic criteria, this definition generally involves the clinical findings of fever, abdominal pain, neutropenia, and thickening of the abdominal wall (usually the cecum and ascending colon) through imaging studies.[9] In spite of determining the final diagnosis by biopsy, NE is principally a clinical diagnosis. Tissue samples from the colon are not usually taken from surviving patients. Despite needing unison diagnostic criteria, some meta-analysis could define diagnostic criteria based on common clinical and laboratory features found on patients. As major criteria, they described fever (temperature >38.3C), abdominal pain, bowel wall thickening diagnosed by CT or ultrasound (>4 mm thickening for ≥30 mm length), and neutropenia (defined as ANC <500 × 10^9 cells/L). Between the minor criteria, they defined abdominal distension, cramping, diarrhea, and lower gastrointestinal bleeding.[11]

Part of the diagnosis involves using imaging studies that try to elucidate between diverse differential diagnosis. Furthermore, the need for a radiological confirmation is discussed but recommended by many authors. Abdominal plain X-rays allow us to see characteristics as a dilated atonic cecum and ascending colon filled with liquid levels or gas, marks of intramural gas, and small bowel dilation. Despite this, the simple imaging technique has limited value due to its reduced sensitivity and specificity.[14]

As for other imaging studies, ultrasound and CT are the present supports for the diagnosis of NE. Reports seem to support the use of CT if there are other considerations regarding other diagnoses among multiple disorders that can be the reason for different measures of bowel wall thickening (BWT). Furthermore, NE characteristics, such as BWT, nodularity, the existence of pneumatosis, and the amount of distension, were better seen on CT. However, the value of ultrasound may have advantages in terms of ascertaining the existence of BWT and promptly ruling out other causes in the differential diagnosis, including appendicitis, intussusception, cholecystitis, or pancreatitis.

Treatment / Management

Neutropenic enterocolitis treatment is still controversial. In general, traditional management consists of aggressive fluid resuscitation, correction of electrolyte imbalance, bowel rest, abdominal decompression, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Improvement of thrombocytopenia and clotting abnormalities can require blood component transfusion.Since different pathogens were identified on the tissue biopsies, the IDSA guideline recommends broad-spectrum antibiotics for febrile neutropenia. For instance, if we choose a cephalosporin as part of the treatment, the addition of anaerobic coverage (with metronidazole or oral vancomycin) should be considered because the progression of infection in neutropenic patients is fast and patients with early bacterial infections cannot be genuinely distinguished from non-infected patients at presentation.[15] To guide which kind of regimen to follow, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) 2002 guidelines reported a monotherapy or combined therapy to start empiric antibiotic therapy in febrile high-risk neutropenic patients. These are a monotherapy as cefepime, combined therapy of ceftazidime or a carbapenem, or duo therapy with an antipseudomonal b-lactam antibiotic in combination with an aminoglycoside.(B3)

Severe hemorrhage with hemodynamic instability has also been reported, and these patients should undergo immediate interventional radiologic procedures (i.e., angiography with embolization) in an attempt to avoid surgery.

Considerations for the use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) according to the current American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines include profound neutropenia (absolute neutrophil <100/mL), uncontrolled primary disease, pneumonia, hypotension, multiorgan dysfunction, and invasive fungal. In general, the power of data in the literature concerning the therapy of neutropenic enterocolitis is generally feeble.[14](A1)

Surgeons and oncohematologists are usually hesitant to select surgery as the first-choice treatment as the potential risks associated with abdominal surgery during neutropenia, which is moreover frequently associated with thrombopenia. Nevertheless, no published studies supported this idea. Moreover, neutropenia is not counted anymore as an unfavorable prognostic factor in critically ill cancer patients, as recently published in a large meta-analysis.[15] Surgery even seemed as good prognosis factor in a recent publication in neutropenic patients with cancer and acute abdominal pain.[9] (B2)

The choice for surgical intervention is usually reserved for selected cases of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) based on criteria that were initially established by Shamberger et al.[15] These include (a) the persistence of gastrointestinal bleeding despite correction of coagulopathies, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia; (b) free air in the intraperitoneal cavity indicative of bowel perforation; (c) clinical deterioration despite optimal medical management, and (d) the development of other indications for surgery, such as appendicitis. Conservative management is recommended initially when these criteria are absent.(B3)

To conclude, initial medical treatment consists of bowel rest, fluid resuscitation, total parenteral nutrition, and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Consideration for antifungal therapy is reasonable, although published guidelines did not provide a recommendation for its routine use. Correction of thrombocytopenia and clotting abnormalities is necessary, especially in patients considered for surgery. G-CSF should be considered in patients with fever and neutropenia who are at high risk for infection-associated complications or who have prognostic factors that are predictive of poor clinical outcomes.[16]

Differential Diagnosis

Despite having parameters for a more accurate diagnosis, it has become easier to contemplate other medical entities. Furthermore, CT scans and other methods provide part of a relative help to the correct diagnosis because the definitive parameters are not all established yet. Several other entities can cause gastrointestinal signs and symptoms in patients with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in very similar presentation, so we have appendicitis, C. difficile colitis, and the following:[6]

- Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis

- Gastroenteritis

- Ischemic colitis

- Ogilvie syndrome (colonic pseudo-obstruction)

- Acute appendicitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

In summary, we believe that, until better evidence is available, the vast differential diagnosis can complicate a prompt treatment. The determination of the diagnosis relies on suspicion of NE, trained physicians, clinic judgment, and the use of imaging studies. Although the pathologic confirmation is the last and most reliable diagnostic tool, this method is not helpful for the clinical decision-making as the patients’ condition often makes biopsy difficult and unviable.

Prognosis

A high index of clinical suspicion and appropriate personalized management is essential to achieve a lower mortality rate. There are studies that describe a high mortality rate of up to 50% as most of the compromise is by necrosis, perforation, and sepsis. Other studies in the autopsy of children showed incidence rates as high as 46%, while other studies from ICU patients could potentially reach a mortality rate of up to 100%.[17][18][17] Other factors, such as massive rectal bleeding, may complicate the course of typhlitis, while surgery or embolization of enteral vessels may be lifesaving.

Historically, neutropenic enterocolitis was described as an ominous complication in earlier investigations in the oncologic patient population, with mortality rates ranging from 50% to 100%.[17] Recent accounts in this group have reported lower mortality rates of 30% to 50% for the better suspicion and assessment of NE.[19] Moreover, a recent study showed a mortality rate of 32.1% in the intensive care unit patients and a hospital mortality rate of 38.8%.[18]

Other aspects have been taken into consideration in relation to prognostic power. For instance: American Society of Clinical Oncology Bowel Wall Thickness (BWT). The prognostic significance seen on ultrasound is a matter of some debate, with measurements exceeding 10 mm indicating a poor outcome. But it’s important to remember that this BWT can be found as false-negative in these neutropenic patients. Moreover, Cartoni et al. demonstrated in a large retrospective study that the extent of bowel wall thickening is also a valuable prognostic factor, which unfortunately affects the outcome negatively. In patients without bowel wall thickening, even no mortality was observed.[19]

Still, the prognosis can be poor due to other complications such as malignancy, sepsis or bowel necrosis, and perforation that can occur. All these statistics have shown better outcomes regarding increased awareness, prompt recognition, and better medical and surgical management of NEC.

Complications

- Bowel perforation leading to peritonitis and abscess formation

- Sepsis and septic shock leading to death

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

Consultations

- Gastroenterologist

- Oncologist

- General or colorectal surgeon if needed

- Interventional radiologist if needed for drainage of abscess or fluid collection or angiogram with embolization in patients with severe bleeding

Deterrence and Patient Education

To conclude, neutropenic enterocolitis (NE) is a serious complication with high mortality. The pathogenesis is not well understood. The diagnosis is clinical in patients who meet all of the following criteria: Fever, abdominal pain, and bowel wall thickening. The US or CT should be performed immediately in these patients. Patients with a diagnosis of NE should be generally administered broad-spectrum antibiotics according to the guideline (e.g., IDSA) recommendations for febrile neutropenia. If a cephalosporin is chosen, the addition of anaerobic coverage should be considered.

Standardized recommendations about indications for surgery cannot be made, but most patients are probably not candidates for surgical intervention, indications include bowel perforation, massive gastrointestinal bleeding, or the concomitance of other problems as appendicitis.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Neutropenic enterocolitis is a life-threatening condition.

- This condition should be in the differential diagnosis of severe neutropenic patients with abdominal pain and fever.

- CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis helps with the diagnosis along with clinical presentation.

- Conservative management is preferred initially.

- Prompt initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics is essential in suspected patients.

- Surgical treatment is avoided due to neutropenia and thrombocytopenia but considered when complications arise.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Neutropenic enterocolitis is a serious complication with high mortality, and prompt aggressive treatment is essential. High suspicion in patients undergoing chemotherapy is warranted in identifying and treating promptly. Close follow up healthcare team, which includes primary care physician, and oncologist helps identify this condition early.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Singh P, Nayernama A, Christopher Jones S, Amiri Kordestani L, Fedenko K, Prowell T, Bersoff-Matcha SJ. Fatal neutropenic enterocolitis associated with docetaxel use: A review of cases reported to the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Journal of oncology pharmacy practice : official publication of the International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners. 2020 Jun:26(4):923-928. doi: 10.1177/1078155219879494. Epub 2019 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 31594460]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUllery BW, Pieracci FM, Rodney JR, Barie PS. Neutropenic enterocolitis. Surgical infections. 2009 Jun:10(3):307-14. doi: 10.1089/sur.2008.061. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19566419]

Tamburrini S, Setola FR, Belfiore MP, Saturnino PP, Della Casa MG, Sarti G, Abete R, Marano I. Ultrasound diagnosis of typhlitis. Journal of ultrasound. 2019 Mar:22(1):103-106. doi: 10.1007/s40477-018-0333-2. Epub 2018 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 30367357]

Pelletier JH, Nagaraj S, Gbadegesin R, Wigfall D, McGann KA, Foreman J. Neutropenic enterocolitis (typhlitis) in a pediatric renal transplant patient. A case report and review of the literature. Pediatric transplantation. 2017 Sep:21(6):. doi: 10.1111/petr.13022. Epub 2017 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 28664544]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRodrigues FG, Dasilva G, Wexner SD. Neutropenic enterocolitis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Jan 7:23(1):42-47. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i1.42. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28104979]

Nesher L, Rolston KV. Neutropenic enterocolitis, a growing concern in the era of widespread use of aggressive chemotherapy. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013 Mar:56(5):711-7. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis998. Epub 2012 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 23196957]

Gorschlüter M, Mey U, Strehl J, Ziske C, Schepke M, Schmidt-Wolf IG, Sauerbruch T, Glasmacher A. Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults: systematic analysis of evidence quality. European journal of haematology. 2005 Jul:75(1):1-13 [PubMed PMID: 15946304]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHeinz WJ, Buchheidt D, Christopeit M, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Cornely OA, Einsele H, Karthaus M, Link H, Mahlberg R, Neumann S, Ostermann H, Penack O, Ruhnke M, Sandherr M, Schiel X, Vehreschild JJ, Weissinger F, Maschmeyer G. Diagnosis and empirical treatment of fever of unknown origin (FUO) in adult neutropenic patients: guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Annals of hematology. 2017 Nov:96(11):1775-1792. doi: 10.1007/s00277-017-3098-3. Epub 2017 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 28856437]

McCarville MB, Adelman CS, Li C, Xiong X, Furman WL, Razzouk BI, Pui CH, Sandlund JT. Typhlitis in childhood cancer. Cancer. 2005 Jul 15:104(2):380-7 [PubMed PMID: 15952190]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCardona Zorrilla AF, Reveiz Herault L, Casasbuenas A, Aponte DM, Ramos PL. Systematic review of case reports concerning adults suffering from neutropenic enterocolitis. Clinical & translational oncology : official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico. 2006 Jan:8(1):31-8 [PubMed PMID: 16632437]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMiller EE, Reardon LC. Neutropenic Enterocolitis in a Pediatric Heart Transplant Recipient on Multiple Immunosuppressants. Case reports in transplantation. 2018:2018():3264921. doi: 10.1155/2018/3264921. Epub 2018 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 29854547]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSachak T, Arnold MA, Naini BV, Graham RP, Shah SS, Cruise M, Park JY, Clark L, Lamps L, Frankel WL, Theodoropoulos N, Arnold CA. Neutropenic Enterocolitis: New Insights Into a Deadly Entity. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2015 Dec:39(12):1635-42. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000517. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26414225]

Kaito S, Sekiya N, Najima Y, Sano N, Horiguchi S, Kakihana K, Hishima T, Ohashi K. Fatal Neutropenic Enterocolitis Caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: A Rare and Underrecognized Entity. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2018 Dec 15:57(24):3667-3671. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.1227-18. Epub 2018 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 30101922]

Ozer H, Armitage JO, Bennett CL, Crawford J, Demetri GD, Pizzo PA, Schiffer CA, Smith TJ, Somlo G, Wade JC, Wade JL 3rd, Winn RJ, Wozniak AJ, Somerfield MR, American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2000 update of recommendations for the use of hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors: evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines. American Society of Clinical Oncology Growth Factors Expert Panel. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2000 Oct 15:18(20):3558-85 [PubMed PMID: 11032599]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShamberger RC, Weinstein HJ, Delorey MJ, Levey RH. The medical and surgical management of typhlitis in children with acute nonlymphocytic (myelogenous) leukemia. Cancer. 1986 Feb 1:57(3):603-9 [PubMed PMID: 3484659]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoir DH, Bale PM. Necropsy findings in childhood leukaemia, emphasizing neutropenic enterocolitis and cerebral calcification. Pathology. 1976 Jul:8(3):247-58 [PubMed PMID: 1004950]

Alt B, Glass NR, Sollinger H. Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults. Review of the literature and assessment of surgical intervention. American journal of surgery. 1985 Mar:149(3):405-8 [PubMed PMID: 3856402]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDuceau B, Picard M, Pirracchio R, Wanquet A, Pène F, Merceron S, Mokart D, Moreau AS, Lengliné E, Canet E, Lemiale V, Mariotte E, Azoulay E, Zafrani L. Neutropenic Enterocolitis in Critically Ill Patients: Spectrum of the Disease and Risk of Invasive Fungal Disease. Critical care medicine. 2019 May:47(5):668-676. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003687. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30741755]

Cartoni C, Dragoni F, Micozzi A, Pescarmona E, Mecarocci S, Chirletti P, Petti MC, Meloni G, Mandelli F. Neutropenic enterocolitis in patients with acute leukemia: prognostic significance of bowel wall thickening detected by ultrasonography. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2001 Feb 1:19(3):756-61 [PubMed PMID: 11157028]