Introduction

Echocardiography uses ultrasound waves that obtain cardiac views of the heart and great vessels probed with an ultrasound probe. [1][2][3][4]There are four basic rescue views that are probably the most useful in helping to determine the possible cause of the cardiac arrest and are all easily obtained.

Indications

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Indications

Indications for a limited rescue four-view exam include the unstable patient with unexplained hemodynamic disturbances, suspected valve disease, thromboembolic problems, transesophageal echocardiography guided CPR in emergency department cardiac arrest both for diagnosis and monitoring effective cardiopulmonary CPR.

Contraindications

Contraindications include esophageal disease with known stricture, diverticuli, varices or tumor, prior esophageal or stomach surgery, perforated viscus, or an uncooperative patient. Relative contraindications include cervical spine disease, hiatal hernia, coagulopathy, prior chest radiation, or facial or airway trauma.

Equipment

Equipment includes a transesophageal (TEE) probe, ultrasound machine, and adequate amount of gel.

Preparation

The patient needs to have tracheal intubation and have cardiac monitoring prior to TEE probe placement.

Technique or Treatment

A well-lubricated TEE probe is introduced into the midline of hypopharynx with transducer facing anteriorly, and the probe is advanced into the esophagus.

During this maneuver, the control knob must be in a neutral position. The tip of TEE scope can be angled upward or downward by a lever, just as a bronchoscope or flexible laryngoscope. Additionally, the TEE scope has a flat head that looks something like a Pez or a miniature brick. Inside that brick is a movable transducer called the ‘multiplane.' The multiplane is steered with a button reachable by the thumb of the hand that is holding the handle. The other hand is usually in the patient’s mouth, keeping the scope from rotating or inadvertently sliding in and out. The different views are obtained by a combination of rotating the multiplane and pointing the tip of the scope. [5][6][7]

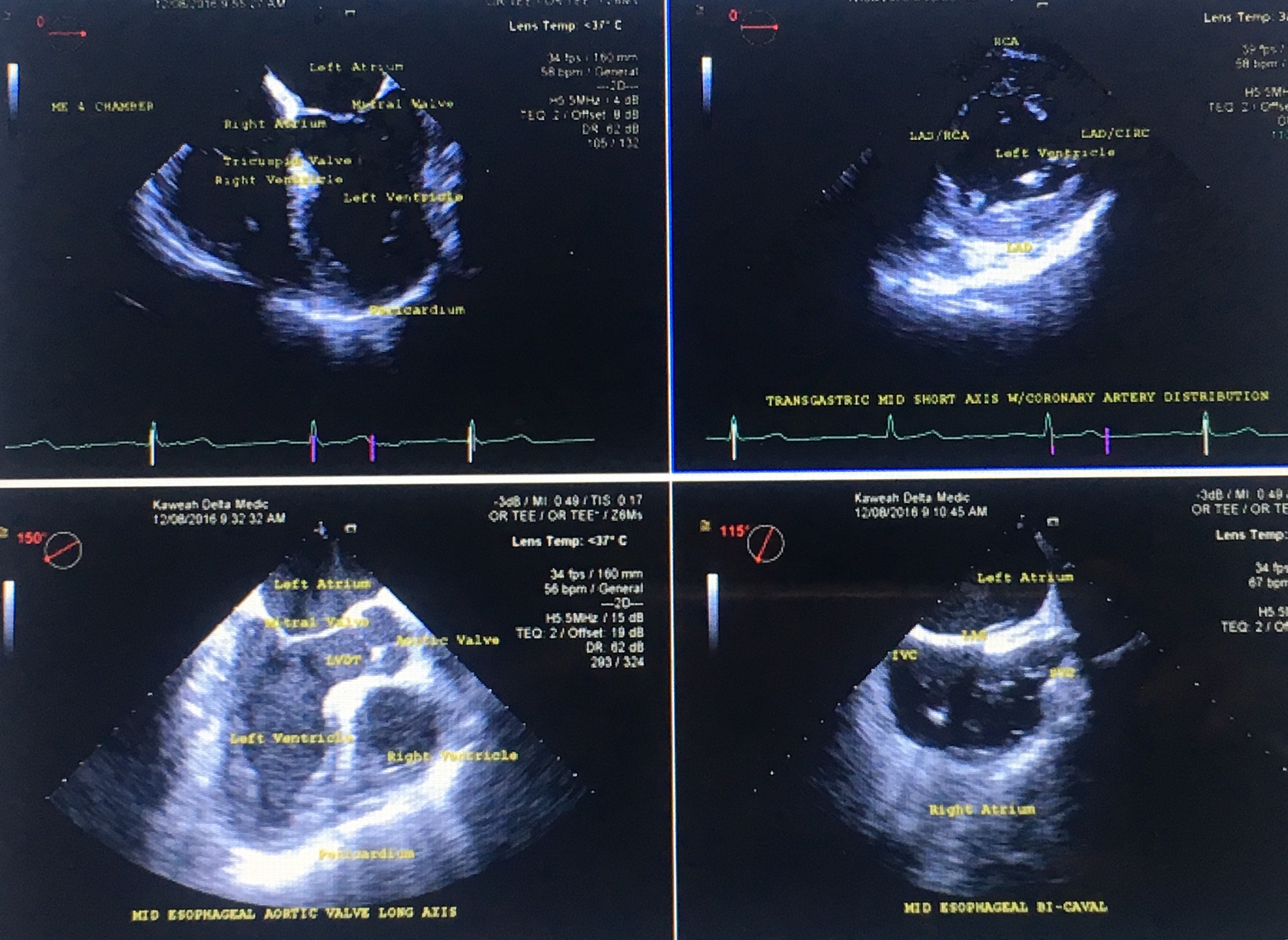

Midesophageal Four-Chamber View (MEFC)

The most diagnostically valuable, and the easiest to obtain view is the Midesophageal Four-Chamber view (MEFC). This view is obtained when the TEE probe is first inserted with the multiplane set at zero degrees, that is, not rotated. With minimal to no manipulation, one can see all four chambers of the heart, the mitral and tricuspid valves, the septal and lateral walls of the left ventricle (LV), the free wall of the right ventricle (RV), and the pericardium. This view can show the effectiveness of the chest compressions, the degree of forwarding blood flow, fluid status, ventricular function, presence/absence of fine ventricular fibrillation (Vfib), and the presence/absence of a significant pericardial effusion and possible tamponade. An extremely dilated RV with free wall akinesis and normal apical contractions (McConnell Sign) is highly diagnostic for an acute, massive PE. Sometimes a thrombus can be visualized in the RA or RV in this view. If so, perhaps a PE caused the cardiac arrest. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) is not the preferred imaging study for diagnosing PE, but it does offer useful information when the patient is too unstable to go to CT or MRI.[8][9]

Transgastric, Midpapillary Short Axis View (TGMPSA)

The second view is the transgastric, midpapillary, short axis (TGMPSA) view. As the name indicates, this view has the scope pushed into the patient’s stomach and the tip turned to look back on itself. The tip is anteflexed, since the heart is superior to and slightly anterior to the cardioesophageal junction. After anteflexion, the probe is withdrawn and the LV will come into view in its short axis. Ideally, the LV will look like a "doughnut" with both papillary muscles inside the doughnut on the screen. With the proper depth of view, the papillary muscles should be equal in size. This image also is obtained with the multiplane at zero degrees, like the MEFC view, but may require some slight rotation of the scope or of the multiplane to obtain an optimal image of the LV.

The TGMPSA view examines LV function and sees wall motion abnormalities. The location of wall motion abnormalities can indicate which coronary artery or arteries are occluded. Knowing which wall is hypokinetic will tell the cardiologist which vessel to catheterize first thus saving the patient critical time. Knowing where the infarct is, the cardiologist may not need to do an LV angiogram, and thereby reduce the amount of angiographic dye a patient receives. In turn, this reduces the burden on the patient’s already compromised kidneys.

On the TGMPSA, one also can see the pericardium, look for pericardial fluid, and roughly estimate the amount. If there is a tamponade, this view can be used to guide placement of a drainage needle or catheter. Although technically more difficult, this view provides much of the same information as the MEFC view with the extra benefit of seeing which coronary artery’s distribution is hypokinetic and estimating LV function.

For further aortic evaluation, one can rotate the probe to the patient’s left. The aorta in short axis (cross section) comes into view to answer whether there is an aortic dissection or an aneurysm.

Before removing the probe, re-set the flexion to neutral and the multiplane to zero degrees. Then, pull it out slowly to the upperesophageal position. From there, look at the descending aorta and distal aortic arch.

Midesophageal Long Axis View (MELA)

The Midesophageal Long Axis (MELA) view is obtained with the probe at the midesophageal depth, and multiplane angle is rotated by approximately 120 degrees, or to the point where the LV outflow tract is seen. One can see the LV inflow and outflow tracts as well as the mitral and aortic valves. One also can see dissection or dilatation of the proximal ascending aorta and LV anteroseptal and inferolateral wall motion abnormalities.

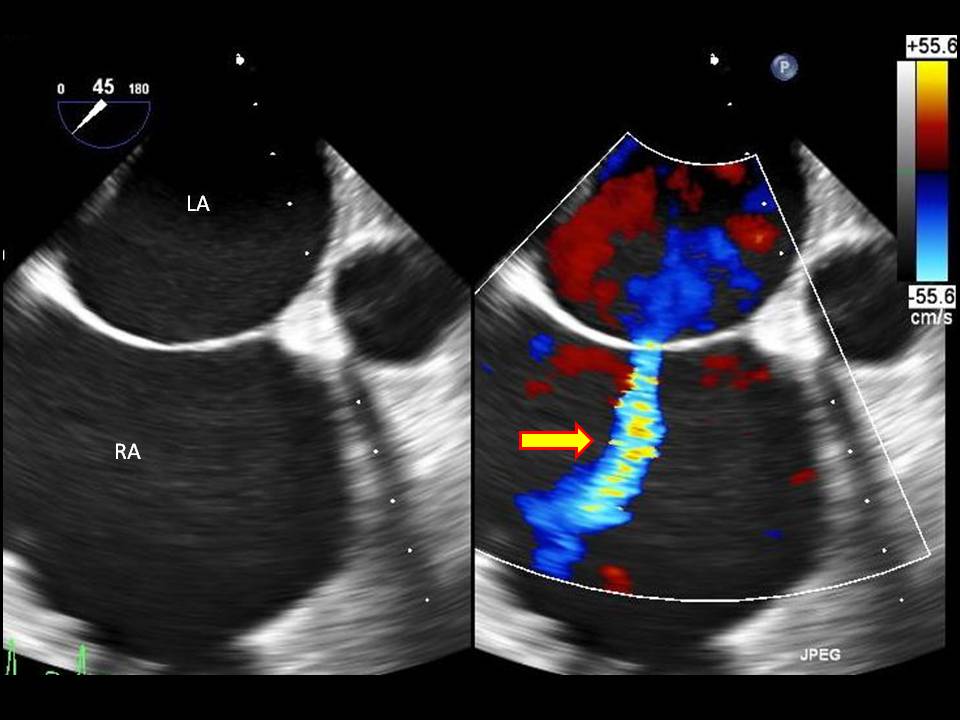

Midesophageal Bicaval View (MEBC)

From the MELA position, rotate the scope towards the patient’s right (clockwise if one looks from head caudally along a supine patient). This brings the left and right atria into view. This view is called the Midesophageal Bicaval (MEBC) It may require decreasing the angle of the multiplane by some 5 to 15 degrees. One will see the left atrium (LA) at the top of the screen, the right atrium (RA) in the middle of the screen, the inferior and superior vena cava, the inter-atrial septum and RA appendage. This is a good screening view to search for a clot in the IVC or RA if PE is suspected. RA size can also be assessed.

The first two views, (MEFC view and the TGLV short axis view) are the most important in the setting of cardiac arrest. The EP should concentrate on mastery of these two views.

Complications

The most dangerous complication is esophageal perforation with a (0.03%) complication rate.

Clinical Significance

When the patient presents to the ED in cardiac arrest, TEE can provide valuable information, quickly and at low risk, and therefore improve outcome and patient survival. In acute myocardial infarction, TEE visualization of the hypokinetic area of the myocardium can inform the cardiologist of the affected vessel, quantify ejection fraction, guide intra-arterial balloon placement, help look at the patient’s volume status, identify unstable etiology, and guide management.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

TEE is often performed by the cardiologist to assess the heart structures. It is more sensitive than a transthoracic procedure. However, it is important to have the nurse monitor the patient during the procedure. A relatively common complication of the procedure is perforation of the esophagus and hence a chest X-ray should be obtained after the procedure. If the tear is small, then the chest x-ray may be normal but symptoms may appear within 24-48 hours.[10]

Media

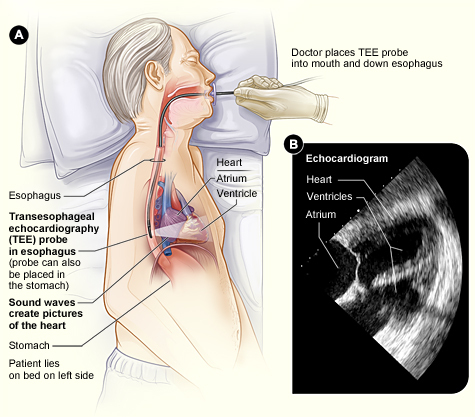

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Figure A shows a transesophageal echocardiography probe in the esophagus, behind the heart. Sound waves from the probe create high-quality pictures of the heart. Figure B shows an echocardiogram of the heart’s lower and upper chambers (ventricles and atrium, respectively). Contributed by Wikimedia Commons, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NIH)

(Click Video to Play)

Transesophageal Echocardiogram. Transesophageal echocardiogram, before and after patent foramen ovale closure, revealing delayed intracardiac shunting and hypoxemia after massive pulmonary embolism.

Weig T, Dolch M, Frey L, et al. Delayed intracardial shunting and hypoxemia after massive pulmonary embolism in a patient with a biventricular assist device. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:133.

doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-133.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Vesteinsdottir E, Helgason KO, Sverrisson KO, Gudlaugsson O, Karason S. Infections and outcomes after cardiac surgery-The impact of outbreaks traced to transesophageal echocardiography probes. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2019 Aug:63(7):871-878. doi: 10.1111/aas.13360. Epub 2019 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 30888057]

Park J, Lee M, Kim J, Choi HJ, Kwon A, Chung HS, Hong SH, Park CS, Choi JH, Chae MS. Intraoperative Management to Prevent Cardiac Collapse in a Patient With a Recurrent, Large-volume Pericardial Effusion and Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation During Liver Transplantation: A Case Report. Transplantation proceedings. 2019 Mar:51(2):568-574. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.12.019. Epub 2019 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 30879592]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSaraçoğlu E, Ural D, Kılıç S, Vuruşkan E, Şahin T, Ağaçdiken Ağır A. Left atrial appendage 2D-strain assessed by transesophageal echocardiography is associated with thromboembolic risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. Turk Kardiyoloji Dernegi arsivi : Turk Kardiyoloji Derneginin yayin organidir. 2019 Mar:47(2):111-121. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2019.39482. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30874509]

Kelly C, Ockerse P, Glotzbach JP, Jedick R, Carlberg M, Skaggs J, Morgan DE. Transesophageal echocardiography identification of aortic dissection during cardiac arrest and cessation of ECMO initiation. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2019 Jun:37(6):1214.e5-1214.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.02.039. Epub 2019 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 30862393]

Chenkin J, Hockmann E, Jelic T. Simulator-based training for learning resuscitative transesophageal echocardiography. CJEM. 2019 Jul:21(4):523-526. doi: 10.1017/cem.2019.13. Epub 2019 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 30854995]

Su FW, Ting CK, Liou JY, Chen YC, Tsou MY, Wang SC. Previously published drug interaction models predict loss of response for transoesophageal echocardiography sedation well but not response to oesophageal instrumentation. Scientific reports. 2019 Mar 7:9(1):3806. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40366-3. Epub 2019 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 30846741]

Stöbe S, Metze M, Spies C, Hagendorff A. [Transesophageal echocardiography in emergency and intensive care medicine : Indication and implementation]. Medizinische Klinik, Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin. 2019 Sep:114(6):490-498. doi: 10.1007/s00063-019-0549-8. Epub 2019 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 30830290]

Jankajova M, Kubikova L, Valocik G, Candik P, Mitro P, Kurecko M, Sabol F, Kolesar A, Kubikova M, Vachalcova M, Dvoroznakova M. Left atrial appendage strain rate is associated with documented thromboembolism in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift. 2019 Apr:131(7-8):156-164. doi: 10.1007/s00508-019-1469-6. Epub 2019 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 30824998]

Teran F, Dean AJ, Centeno C, Panebianco NL, Zeidan AJ, Chan W, Abella BS. Evaluation of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest using transesophageal echocardiography in the emergency department. Resuscitation. 2019 Apr:137():140-147. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.02.013. Epub 2019 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 30779977]

Herbold T, Chon SH, Grimminger P, Maus MKH, Schmidt H, Fuchs H, Brinkmann S, Bludau M, Gutschow C, Schröder W, Hölscher AH, Leers JM. Endoscopic Treatment of Transesophageal Echocardiography-Induced Esophageal Perforation. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques. Part A. 2018 Apr:28(4):422-428. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0559. Epub 2018 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 29327976]