Introduction

Trichoblastoma (TB) and trichoepithelioma (TE) are benign hair-germ tumors that most commonly arise on the face and scalp of adults (see Image. Trichoblastoma). Brooke first described TE as epithelioma adenoides cysticum in 1892. In 1953, Pinkus further modified its description and then individually by Lever and Montgomery in 1967 to include embryonic origins within pluripotent hair follicle germ cells.[1]

TB was first described in 1970 by Headington as a differentiated follicular neoplasm, and in 1993 was further characterized by Ackerman et al. in 1993 to include all benign hair-germ cell tumors.[2] Although TE and TB are two distinct entities, the former may be considered a subset of the latter.[3] TEs/TBs are benign and rarely metastasize. However, they can transform into trichoblastic carcinoma (TBC), which arises due to the loss of p53 tumor suppressor protein and elevated PI3-AKT signaling in tumor cells. TBC has more potential for local invasion, recurrence, and metastasis.[4]

Epidemiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Epidemiology

The exact incidence and prevalence of TE/TB in the general population (as well as familial genetic syndromes) are not known, but cases are rare. Most sporadic lesions present in adults aged 40 or older.[3] Brooke-Spiegler syndrome predominantly affects young women (male-to-female ratio of 1:6-9.6).

Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome may also have spiradenomas and cylindromas. MFT is a phenotypic variant of this condition characterized by numerous TEs primarily located on the nasolabial folds and inner eyebrows.[7]

Pathophysiology

The etiology and pathophysiology of TE and TB are only partially understood. TE is derived from epithelial-mesenchymal cells, and multiple TEs may be associated with a familial genetic condition called multiple familial trichoepithelioma (MFT). MFT is a disorder linked to two autosomal dominant mutations affecting tumor suppressor genes. The first gene is on chromosome 9q21.[5]

The second is the cylindromatous tumor suppressor gene (CYLD) on chromosome 16q12-q13, which is also the gene implicated in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.[6] This leads to a loss of function of the deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD, which results in elevated NFκB signaling. These patients present with multiple TBs beginning in adolescence/early adulthood.[1]

Like TE, most cases of TB present sporadically and in isolation. Most solitary TB lesions are associated with 9q22.3 mutations.[2]

Histopathology

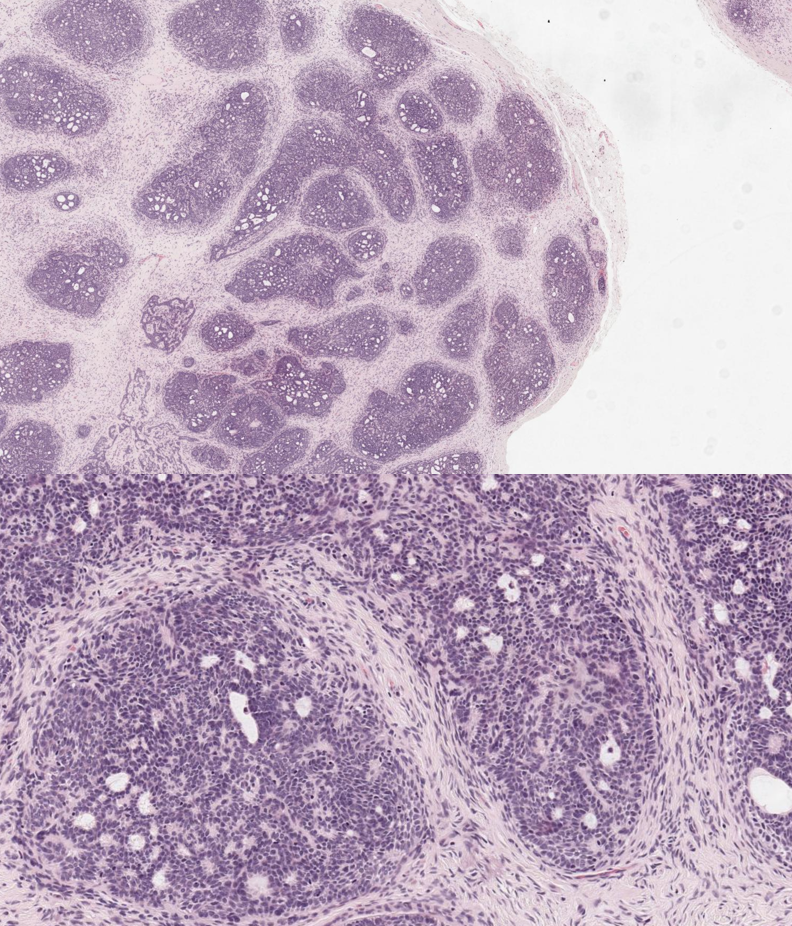

TE and TB are two common benign histologic mimickers of basal cell carcinoma. Histologically, TB appears as a sizeable dermal tumor without connection to the epidermis. It is well-circumscribed and composed of primitive basaloid cells that may arrange in multiple large or small nodules.

TE appears similar to TB; however, tumor cells appear more mature and may be accompanied by horn cysts (i.e., foci of excessive keratinization) and have a connection to the epidermis. Both TE and TB exhibit peripheral palisading and spindled-fibroblast follicular stroma without mucin. Papillary mesenchymal bodies (tumor-cupping oval stromal blebs) are not always seen; when seen, they are specific for benign hair germ-cell tumors.[8]

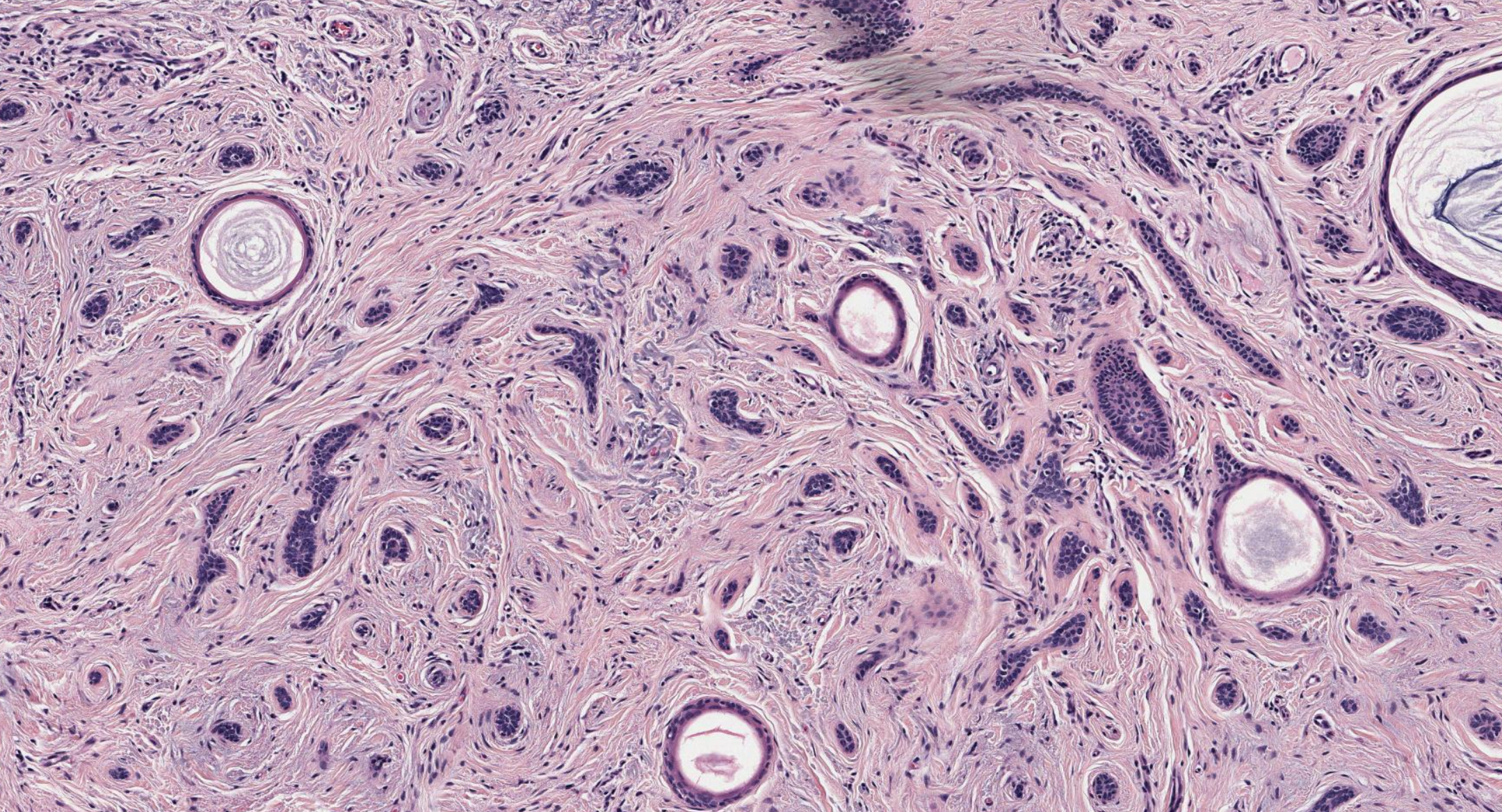

A histologic variant of TE is desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE), which presents with narrow strands of basaloid cells accompanied by keratinized horn cysts and fibrous, desmoplastic stroma (see Image. Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma).[9]

Multiple histologic variants of TB exist according to the updated 2018 World Health Organization (WHO) "Skin Tumors" classification, including nodular, retiform, cribriform, racemiform, and columnar. Less common variants of TB include clear cell, pigmented, and adamantinoid. Furthermore, dermatopathologists may recognize TE as a variant of TB with smaller tumor nodules and more superficial clusters of cells, and abundant fibrotic stroma. "Conventional" and "desmoplastic" TE may also be reported as "cribriform" and "columnar" TE, respectively. Another rare adamantine variant of TB has been described, referred to as cutaneous lymphadenoma, due to the prominent lymphocytic infiltrates within tumor nests.[10]

History and Physical

Typically, TE/TB presents as tiny (0.2 to 1 cm) skin-colored, slow-growing papules or nodules, similar to BCC. They often appear on the head (face or scalp) but may be found on the trunk or extremities.[11] Other locations on the body may be affected, too, such as the vulva, and it is not uncommon for lesions to appear without other cutaneous neoplasms (e.g., inverted follicular keratosis, syringocystadenoma papilliferum).[10]

Rarely, TBs may arise in nevus sebaceus (of Jadassohn), which may appear as a translucent and verrucous plaque with central nodularity and pigmentation.[12] On the other hand, DTE often presents as white-to-yellow, firm skin-colored papules, plaques, or nodules with a central indentation on the face or cheeks.[9]

Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome present with multiple nodules (from ten to several hundred) that appear similar to BCC on the head and neck, ranging from 0.5 to 3.0 cm. Multiple confluent lesions involving the scalp may form a “turban tumor.” Rapid enlargement and bleeding may suggest malignant transformation, which occurs in about 5 to 10% of cases.[13] MFT presents with multiple skin-colored papules and nodules, although they may be smaller (5 to 10 mm) and are mainly distributed to the inner eyebrows and nasolabial folds.[14]

Evaluation

Evaluation of TE/TB begins with obtaining patient history and completing a thorough physical exam. Histopathologic examination via skin biopsy is critical due to their clinical similarities to BCC and other adnexal tumors. Due to overlapping histopathologic features, IHC evaluation may be needed. Dermoscopy is unlikely to be of further help, as these lesions demonstrate dermoscopic findings such as arborizing vessels and gray ovoid nests and globules.[10]

A genetic workup may be necessary for patients with multiple or recurrent lesions, including an evaluation of chromosome 9q21 (for MFT) or the CYLD gene (for Brooke Spiegler syndrome).[15]

Treatment / Management

Solitary TEs/TBs are benign and are cured with complete surgical excision. Multiple lesions, especially on the face (as seen with genetic syndromes), are more challenging to address. Mohs surgery may be warranted in centrofacial locations, especially in variants with deep dermal or subdermal infiltration.[16]

Frequent facial surgery may be disfiguring (i.e., scarring) and cause significant distress. Furthermore, multiple TEs/TBs associated with underlying genetic familial syndromes may recur after surgery, leaving numerous scars and invasive treatments throughout a patient’s lifetime.

There is no universally accepted guideline or protocol for treating multiple TEs/TBs. Other than surgical excision, treatment options, such as electrosurgery, dermabrasion, cryotherapy, and radiation therapy, are limited and invasive. Moreover, radiation therapy is associated with an increased risk of other skin cancers. Besides scarring, pain, bleeding, infection, and lesion recurrence are additional risks of these and other invasive surgical therapies.

Laser treatments (such as carbon dioxide, erbium:YAG, and diode) may rapidly remove many lesions safely and effectively without lesion recurrence or causing cosmetic morbidity. Even though they may be minimally invasive, frequent treatments may result in hypertrophic scarring, post-inflammatory hypo- or hyper-pigmentation, and local skin-site inflammatory changes (e.g., edema, erythema, ulceration, burning).

Other pharmacologic agents may be considered, such as sirolimus, imiquimod, tretinoin, vismodegib, aspirin, and adalimumab. However, further clinical trials are warranted as current evidence for these and other medical therapies is anecdotal.[17]

Differential Diagnosis

The primary differential diagnosis is nodular BCC. Tumor cells have elongated nuclei and show prominent palisading along the tumor nodules' periphery, which often extends into the dermis. Major cleft retraction, cytologic atypia, significant mitotic activity, tumor necrosis, or myxoinflammatory stroma may be present. TE/TB often lacks these features. However, similar to TE/TB, BCC tends to arise in sun-exposed skin areas (i.e., face, neck, head).

In challenging cases, cytokeratin 20 (CK20) can distinguish TE/TB from BCC, as this marker routinely stains Merkel cells in benign, hair-germ tumors. This stain may be used alongside androgen receptor (AR) staining when evaluating TE/TB versus BCC, as AR positivity (with CK20 negativity) suggests the latter. However, AR positivity may be focal or completely absent in some cases of BCC.[8]

DTE may histologically appear similar to the morpheaphorm subtype of BCC (MBCC), other adnexal tumors (e.g., syringoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma - MAC), and cutaneous metastatic breast cancer. IHC staining may sometimes help in tumor differentiation; however, correlation with clinical and histologic features remains essential. As opposed to these other entities, DTE routinely expresses CK20-positive Merkel cells.

Although multiple histologic variants of TB exist according to the updated 2018 WHO classification guidelines, CD34 (stromal), BCL-2, CK20, and PHLDA1 positivity may all be used to help distinguish TB from BCC.[10] Also, TBs often lack patch (PTCH) gene mutations, commonly seen in BCC, especially in syndromic variants.[18]

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FeP) is an uncommon BCC variant that may resemble TE/TB. Histology of FeP often shows fenestrated strands of basaloid epithelial tumor cells with significant dermal fibrosis. Peripheral palisading of fenestrations tends to be apparent, and stromal clefting with tumor cell retraction is common. FeP often stains positive for CK20 (85% of cases), AR (77% of cases), and BCL-2.[19]

Another entity closely resembling BCC and TE/TB clinically is basaloid follicular hamartoma (BFH), a rare benign adnexal tumor. Like BCC, BFH arises due to a mutation in PTCH, located on chromosome 9q23. This gene encodes a receptor for the sonic hedgehog pathway, and mutations lead to abnormal tumor cell growth and development (see Image. Trichoblastoma Path). However, BFH classically centers around hair follicles and remains limited to the superficial dermis. Branching cords of basaloid cells can be seen connecting to pilosebaceous units in early disease, and tumor cells may completely replace them in cases of longstanding disease.[20]

Prognosis

The prognosis of solitary TE/TB is excellent. However, the likelihood of lesion recurrence dramatically increases in patients with familial genetic syndromes. Since these lesions predominantly appear in the face or neck, healthcare providers must consider the time, costs, and morbidity associated with frequent invasive treatments.[17]

Complications

As TE/TB are benign entities, surgical excision is curative with a minimal likelihood of disease recurrence or metastasis. Complications of surgery, other invasive treatments, and laser treatments can be found in the “Treatment/Management” section of this chapter.

Deterrence and Patient Education

In cases of solitary lesions, treatment and management of TE/TB are relatively unremarkable, given the benign nature of these tumors. However, in familial genetic syndromes, treatment plans may be more complex due to the risk of lesion recurrence, assortment, and location in cosmetic skin areas (e.g., face).

Patients with multiple lesions or a suggestive family history should communicate this with their providers as further genetic workup may be necessary. Practitioners should also reassure patients that TE/TB is benign and different from BCC.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Histopathologic evaluation of cutaneous adnexal tumors, such as TE/TB, is essential when determining diagnosis and further patient management. As with many conditions, the clinicopathologic correlation of biopsy findings with patient presentation is critical when choosing the most likely diagnoses and the best next management steps.

Given that TE/TB is a frequent mimicker of BCC (both clinically and histologically), a single biopsy may not be enough in some instances. If a patient presents with more extensive or multiple skin tumors that may be concerning for BCC versus TE/TB versus other entities, obtaining several biopsies (either from the same or various tumors) may be best. Given the potential for malignant transformation of TE and TB, complete excision of benign lesions with negative margins is recommended.[21]

Obtaining accurate diagnoses is also essential for decreasing the risk of over-treatment, either by surgical, medical, other invasive, or non-invasive means. As noted in the section on histopathology, the depth of skin lesions is essential for providers to consider. Unnecessary treatment complications are crucial to avoid, and some patients may require skin grafting after lesion excision.[5] [Level 5]

Media

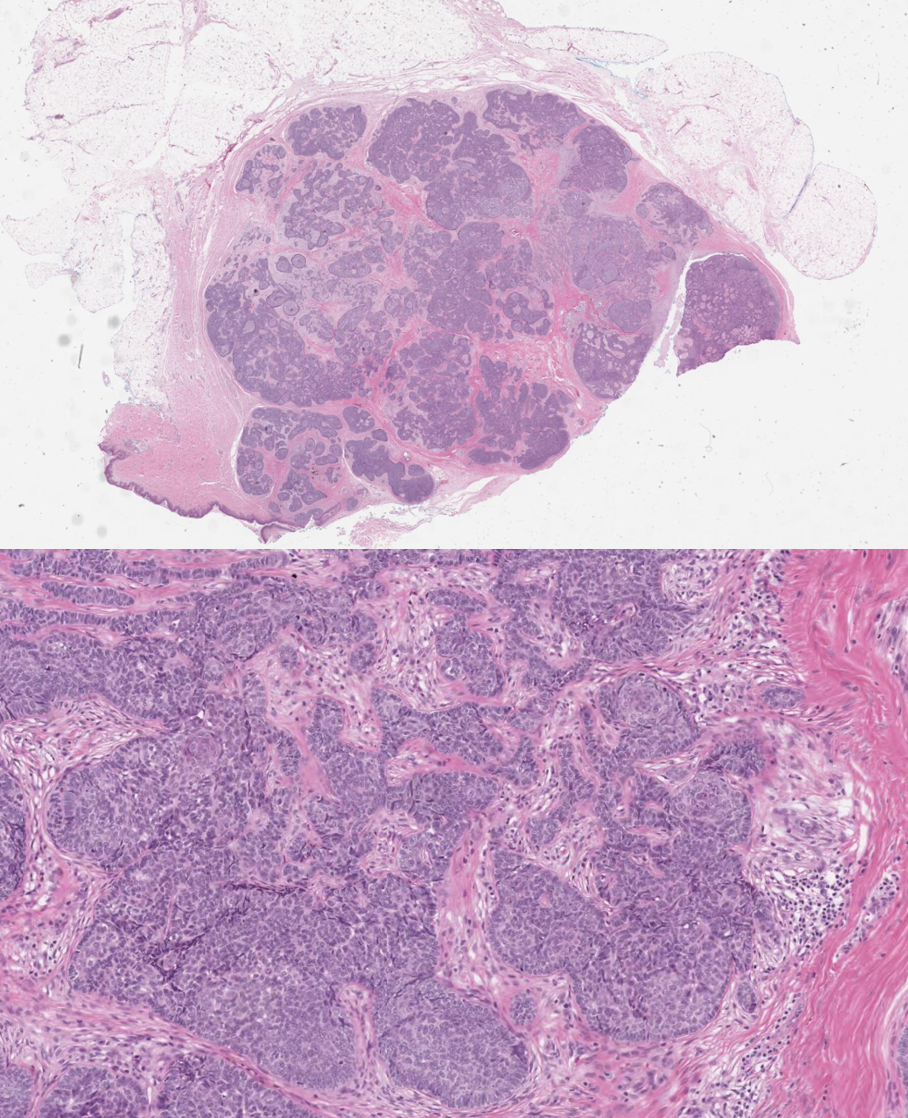

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Trichoblastoma. This image shows a well-circumscribed dermal lesion with epithelial cell aggregates and characteristic follicular stroma, lacking the peritumoral clefting seen in basal cell carcinoma (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnifications ×40 top and ×100 bottom).

Contributed by N Sathe, MD