Introduction

Lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) are diseases caused by defects in single-genes. Enzyme defects cause nearly seventy percent of the LSDs, and the rest are defects in enzyme activator or associated proteins. A gene on a particular chromosome locus transcribes a particular enzyme—improper enzyme-coding results in inactive enzymes. Similarly, defective activators result from mutations in activator genes. Seventy LSDs are described so far, and many more will likely be discovered in the future. Individually, they are rare, but they are common and justify the effort and expenditure invested in researching these conditions as a group.[1]

These conditions cause disease of the organs in which they accumulate and decide the clinical signs and symptoms. Infants and children suffer more severely compared to adults. The clinical features are unique in many children and adults for the same disease. For example, the child's developing brain is more susceptible to insults and manifests symptoms and signs of dysfunction, while this may be milder or absent in adults.

The last decade has observed tremendous advances in understanding many of these conditions. These advances have shown promise in improving the lifespan and quality of life, which hitherto remained dismal. The pathology of LSDs resembles that of some degenerative conditions that present in later life and maybe the connecting link between these two.[2]

Enzyme testing is usually the initial diagnostic test, but genetic analysis of the gene mutations adds precision. There are many modern therapeutic techniques for these conditions. When applied early before organ damage sets in, these therapies have the potential to prevent or delay damage, improve quality of life, and increase lifespan.This article summarizes the latest developments in the pathophysiology, investigations, and treatment of the more common LSDs and will improve healthcare outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The majority of the lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) are caused by mutations in the genes encoding a lysosomal enzyme. These monogenic disorders involve forty different acid hydrolases in the lysosomes. Genes with a specific chromosomal locus encode them.

Many types of mutations can produce a defective enzyme. Generally, a nonsense mutation has a more profound defect than a missense mutation. There are many gene variations for a single disease numbering up to a thousand. Sometimes, mutations run in families, and knowledge of this is essential to screen for that particular defect to maximize genetic testing benefits. In some but not all cases, genotype-phenotype correlations are predictable. The reasons for this variability lie in epigenetic and environmental factors. In some instances, a defective enzyme activator, membrane transporter, or a membrane protein can cause the dysfunction. In mucolipidosis, the enzymes are targeted to the extracellular matrix instead of the lysosome. This targeting defect results in their dysfunction.

Most LSDs have an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. Three have an X-linked inheritance pattern: Hunter disease, Fabry disease, and Danon disease. Some mutations, however, do not produce a defective enzyme and are therefore not relevant to LSDs. Apart from genetics, inflammation and oxidative stress are crucial players in LSDs.[3]

There are several classifications of LSDs. The commonest is according to the accumulated substrate. Many LSDs have the names of the persons who first described the conditions.

The broad categories of LSDs, representative examples within the classes, and the accumulated substrates/defects are:

I. Sphingolipidosis:

Complex sphingosine containing phospholipids accumulate.

All disorders comprise a mutant enzyme. Multiple sulfatase deficiency is the exception and is a post-translational disorder.

A) GM2 gangliosidosis:

- Type A (Tay Sachs disease)

- Type O (Sandhoff disease)

- Type AB (GM2 activator deficiency)

B) Niemann-Pick diseases A, B, and C (transmembrane protein defect C1, soluble non-enzymatic protein defect C2)

C) Gaucher disease types 1, 2, and 3

D) Fabry disease (classic and late-onset types)

E) Metachromatic leukodystrophy

F) Globoid leukodystrophy (Krabbe disease)

G) GM1 gangliosidosis types 1, 2, and 3

H) Multiple sulfatase deficiency

II. Oligosaccharidosis (glycoproteins; all disorders with mutant enzymes):

- Alfa mannosidosis

- Schindler disease

- Aspartylglucosaminuria

- Fucosidosis

III. Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) (mucopolysaccharides a.k.a glycosaminoglycans (GAG); all disorders with mutant enzymes):

- Hurler syndrome

- Scheie syndrome

- Hurler-Scheie syndrome

- Hunter syndrome

- SanFilippo syndrome A, B, C, and D

- Morquio syndrome A and B

- Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome

- Sly syndrome

IV. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (lipofuscin, a waxy pigment):

- CLN 1 through CLN 14

V. Sialic acid disorders (sialic acid):

- Galactosialidosis (enzyme protection protein defect)

- Infantile sialic acid storage disease

- Salla disease (transmembrane protein defect)

- Sialuria

VI. Mucolipidosis (membrane transport protein defect; targeting error):

- Sialidosis I and II (Mucolipidosis I)

- I-cell disease (Mucolipidosis II)

- Pseudo-Hurler-Polydystrophy (Mucolipidosis III)

- Mucolipidosis IV

VII. Miscellaneous:

- Lysosomal Acid lipase deficiency infantile and childhood/adult types (cholesterol esters, triglycerides)

- Pompe disease (glycogen storage disease type II)

- Danon disease (glycogen)

- Cystinosis (cystine)

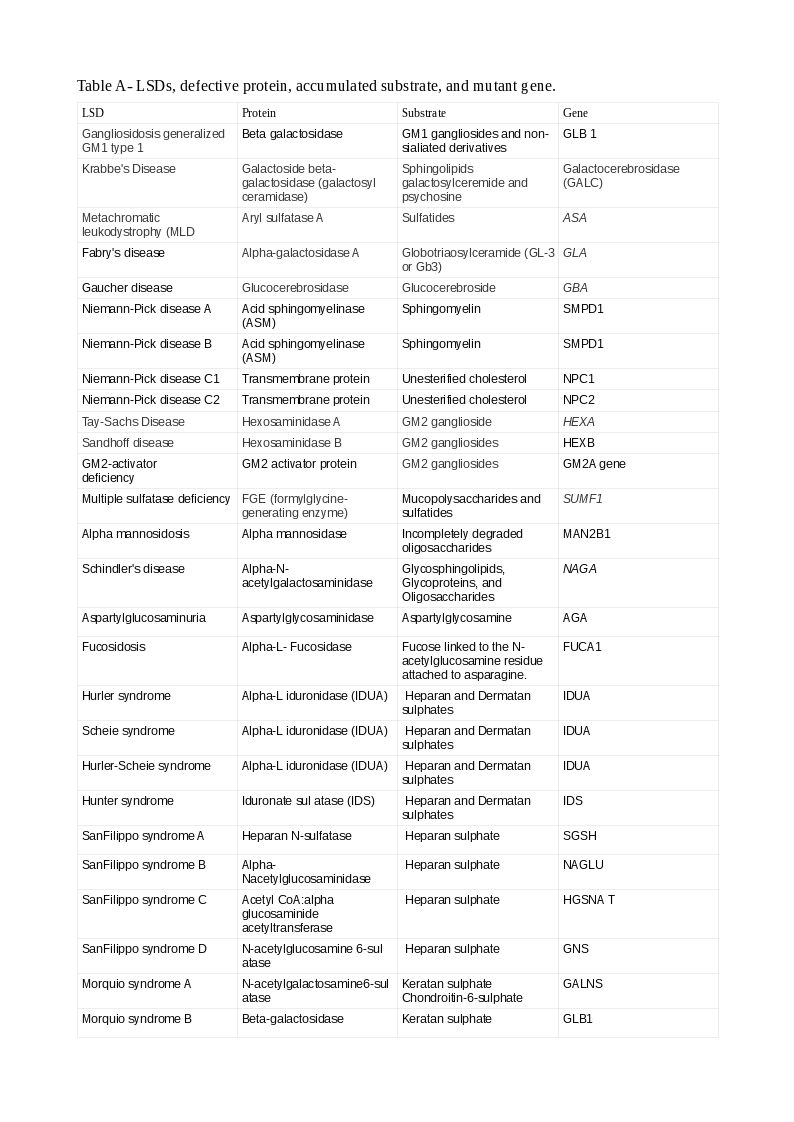

Tables A and B show the LSDs, defective enzyme, gene, and the accumulated substrate. The reader should study both classifications to understand better the causation of LSDs (Note: A protein ending with "ase" is an enzyme, or else, it is a non-enzymatic protein).

Epidemiology

When considered singly, lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) are rare, some very rare, with only a few patients reported in the literature. They occur worldwide; the most common among them are Fabry, Gaucher, Metachromatic leucodystrophy, and Pompe. When viewed as a group, the LSDs are much more common. The combined incidence is between 1 in 5000 to 1 in 8000, depending on which literature one cites.[4]

Both ethnicity and geography play a part in the incidence of LSDs. For example, Gaucher disease(GD) occurs in 1 in 40000 to 1 in 60000 in the general population. In Eastern Europen Jews (Ashkenazi Jews), GD is as high as 1 in 800, Tay-Sachs disease as high as 1 in 3900. Niemann-Pick A and mucolipidosis IV also occur with increased frequency in this population.[5] In the Finnish population, aspartylglucosaminuria occurs at a frequency of 1 in 18500. Salla disease is also common in the Finns. Cultural and geographical genetic isolation with its attendant "Founder Effects" may contribute to this high incidence.

Recently, in a first-ever multi-center pilot newborn screening program for five most common LSDs, around 65000 were screened, sixty-nine were initially positive, and twenty-three of the 69 were confirmed, all reported with late-onset phenotypes.[6] Newborn screening can detect more cases and thereby increasing the incidence of certain LSDs.[7] The true incidence of any of these conditions will depend on accurate diagnosis, proper reporting, and the availability of screening methods inclusive of newborn screening. When screening in all newborns is universally available, the true incidence of all LSDs will be evident.[8]

Pathophysiology

Apart from the recycling of substrates, lysosomes are involved in other crucial functions to cellular homeostasis.

Lysosomes have three major components:

1. Luminal proteins which are either acid hydrolases (enzymes) or their activators.

2. Membrane-integral proteins:

- Structural proteins(amino acid and lipid transporters).

- Ion-channels like calcium channels.

- Trafficking and fusion machinery.[9]

- Membrane catabolic enzymes.

- Vesicular ATPase which functions both as a proton pump and nutrient sensor.

3. Lysosomal associated proteins.

Abnormalities in one or more of the above components can disrupt lysosomal functions and result in LSDs.[10]

The degradation function of lysosomes has three components. Among them, phagocytosis and endocytosis concern extracellular particles. The former leads to the formation of a phagosome and the latter an endosome. The process of degrading endogenous substances is called autophagy. It results in an autophagosome that is then extruded out of the cell by exocytosis.

Besides, lysosomes contribute to the formation of filopodia by fusion with the cell plasma membrane. They also play crucial roles in specialized secretion and plasma membrane repair (by donating membrane). They sense nutritional and other environmental cues. They are dynamically involved in cellular homeostasis, switching between anabolism and catabolism.

Lysosomes extensively communicate with the endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, peroxisomes, and exchange both information and content.[11] The lysosomal enzymes and other proteins are synthesized in the ribosomes and transported to the endoplasmic reticulum(ER), where they are folded and attain a three-dimensional form. Next, they reach the Golgi apparatus for post-translational modification. An example is the addition of glycan residues. They bud off via vesicles to finally fuse with lysosomes. This process is highly integrated and involves specific recognition sites to direct vesicular traffic to the right destination. It involves numerous carrier proteins that are again specific to the compounds they carry. Any step can be affected by a mutation in the genes encoding the various proteins and can result in lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs). Dysfunction of one organelle is likely to affect the proper function of other organelles.[12][2][13][14]

Microtubules are the cell's roadways facilitating transportation. Lysosomes move bidirectionally along these using the motor proteins dynein and kinesin.[15]

Lysosomes production is a transcription regulated process.

Lysosomes have a vital role in:

- Antigen presentation

- Regulation of inflammation

- Autoimmunity

They may be a common denominator for many neurodegenerative, metabolic diseases, and cancer apart from LSDs.[16]

The structural and enzymatic proteins are encoded for by specific genes; mutation in the gene encoding the enzyme results in its deficiency or absence. The corresponding substrate is not catabolized and accumulates within the lysosomes. It leads to swelling of the cells and, over time, organ dysfunction. The compounds upstream accumulate as well, while those downstream are, decreased or absent. It is based on the biochemical tests that show absent or deficient enzyme and high levels of upstream compounds.

When an enzyme activator or structural protein is defective, there is no dearth of the enzyme. The reaction cannot proceed normally, and upstream compounds accumulate, are not moved out of the cell; therefore, accumulating and causing dysfunction. If they manage to leak in excess into the extracellular space, they may leak into body fluids and aid in diagnosis.

Complex cellular substrates undergo degradation into smaller molecules in the lysosomes recycled for further use by cells. Stepwise enzymatic reactions catalyze the degradation of these compounds. A deficient enzyme or accessory protein will prevent the forward reaction and lead to substrate accumulation. The accumulated compounds are excreted and form the basis for measurement in the urine.

In MPS, these compounds are GAG, linked to carbohydrates or, when linked to aminoacids proteoglycans (PTG). The tissue distribution varies with these compounds. Keratan sulfate is present in the cornea, cartilage, intervertebral disks, dermatan sulfate in the heart, blood vessels, and skin. Heparan sulfate is present in the lungs, blood vessels, and on the surface of cells and explains the multiorgan involvement and organ predilection. Similar pathways exist for sphingolipids and other LSDs.

History and Physical

Lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) invariably affect multiple organs. Even within the same disease, the clinical picture can be heterogeneous. Some LSDs present prenatally or very early after birth. Others present in childhood or adulthood. Infant phenotypes have much more severe disease than adults. Certain organs like the central nervous system are more affected in early life. If a prenatal diagnosis of an LSD is available, careful postnatal vigilance can detect symptoms early to enable treatment. Recurrent fetal or neonatal deaths in older siblings or other relatives should herald warning signs to search for an LSD as a probable cause. Some LSDs that present late in life are serendipitously detected in specialty clinics of ophthalmologists, lipidologists, and dialysis centers.

Barring a few conditions, the majority of infants born with an LSD are normal at birth.

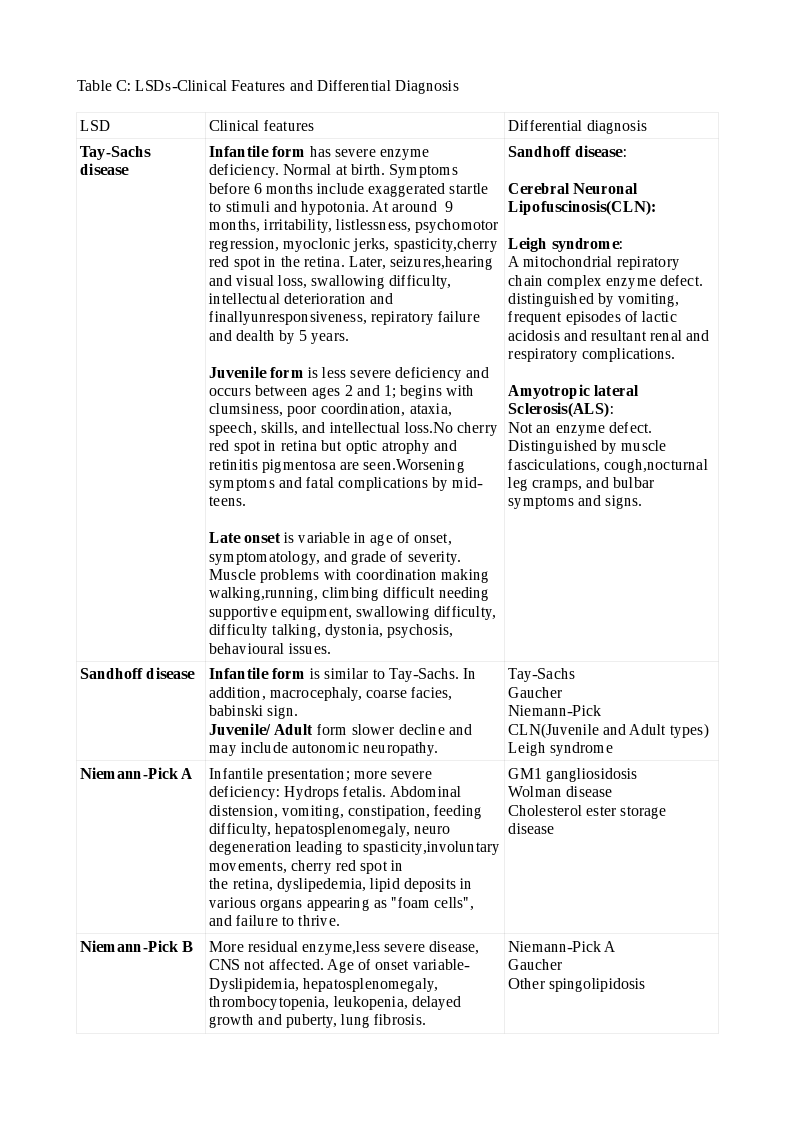

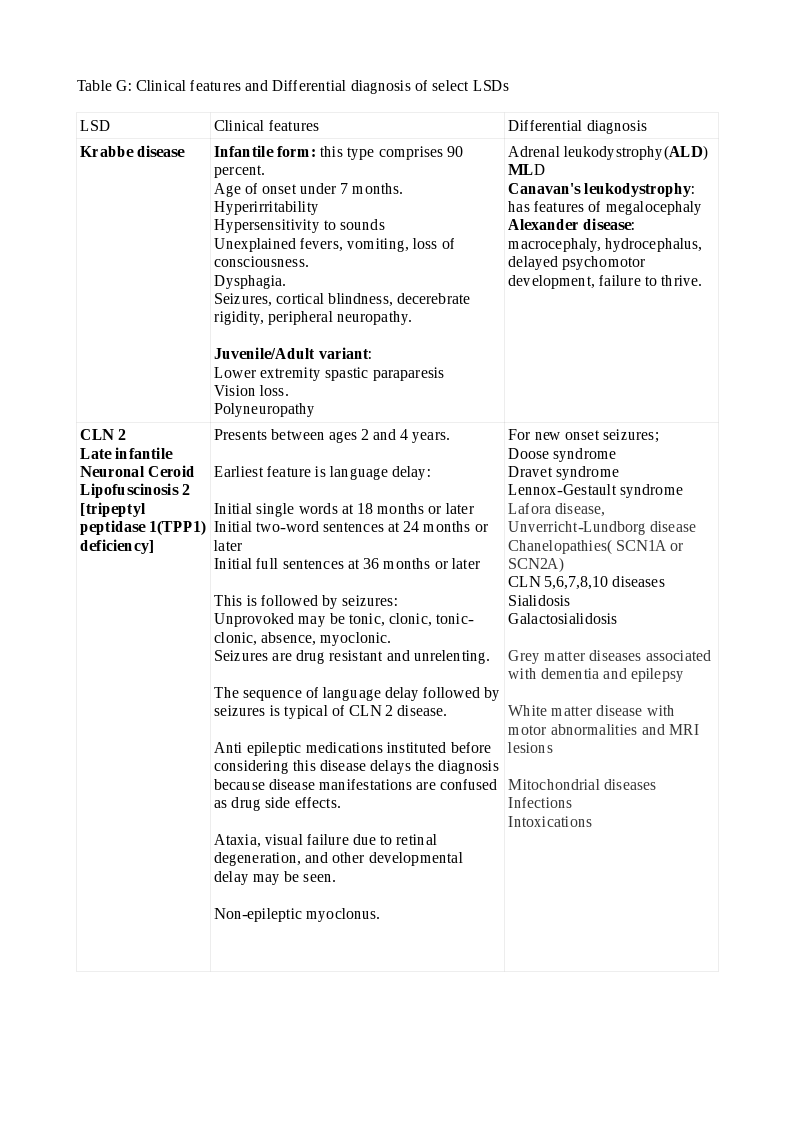

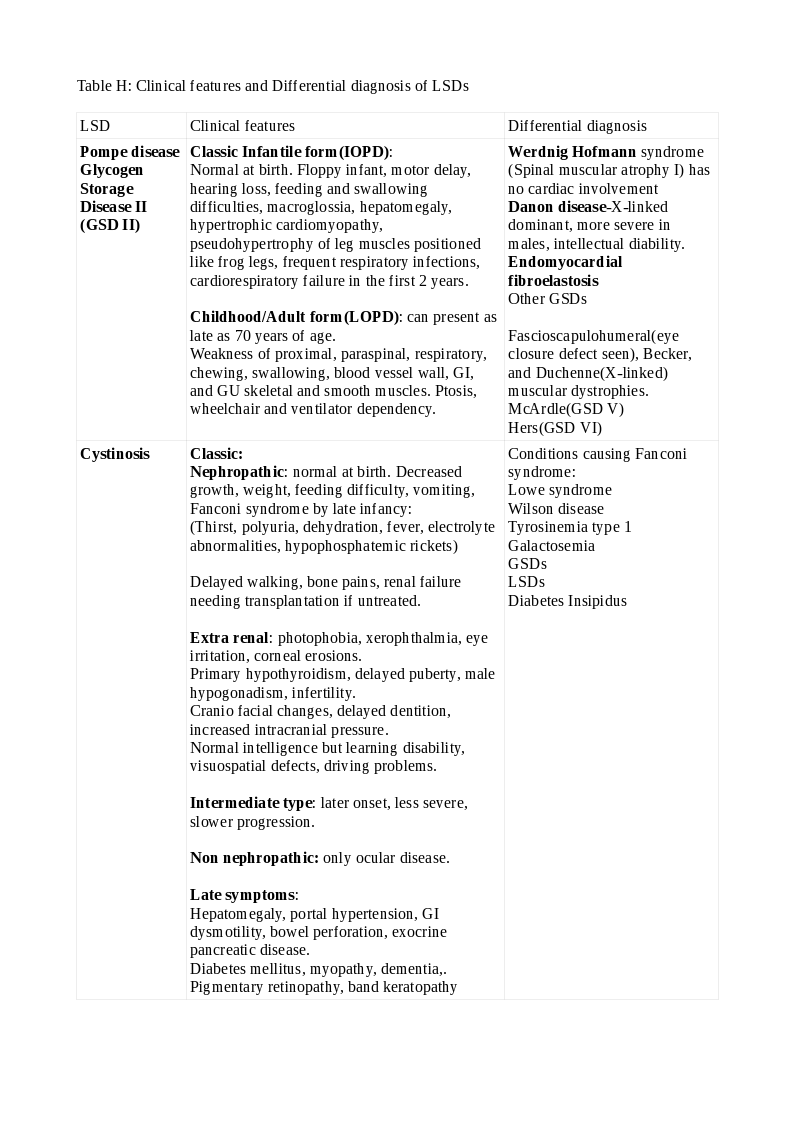

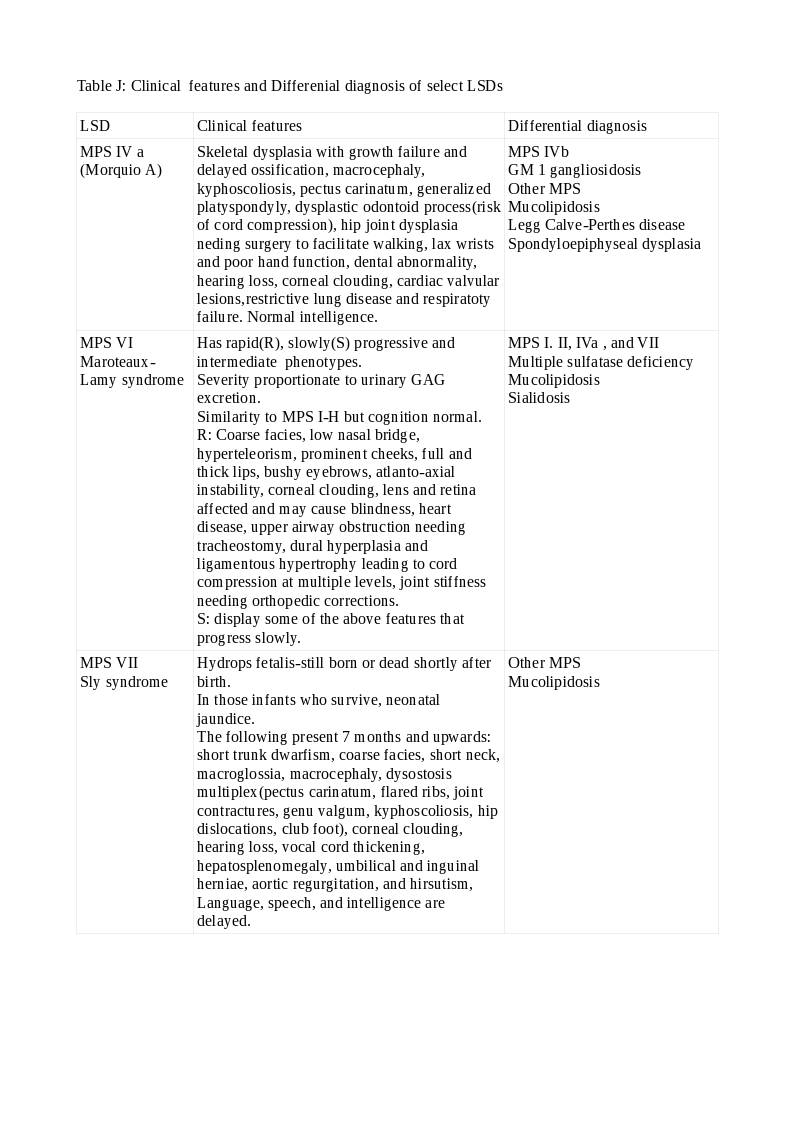

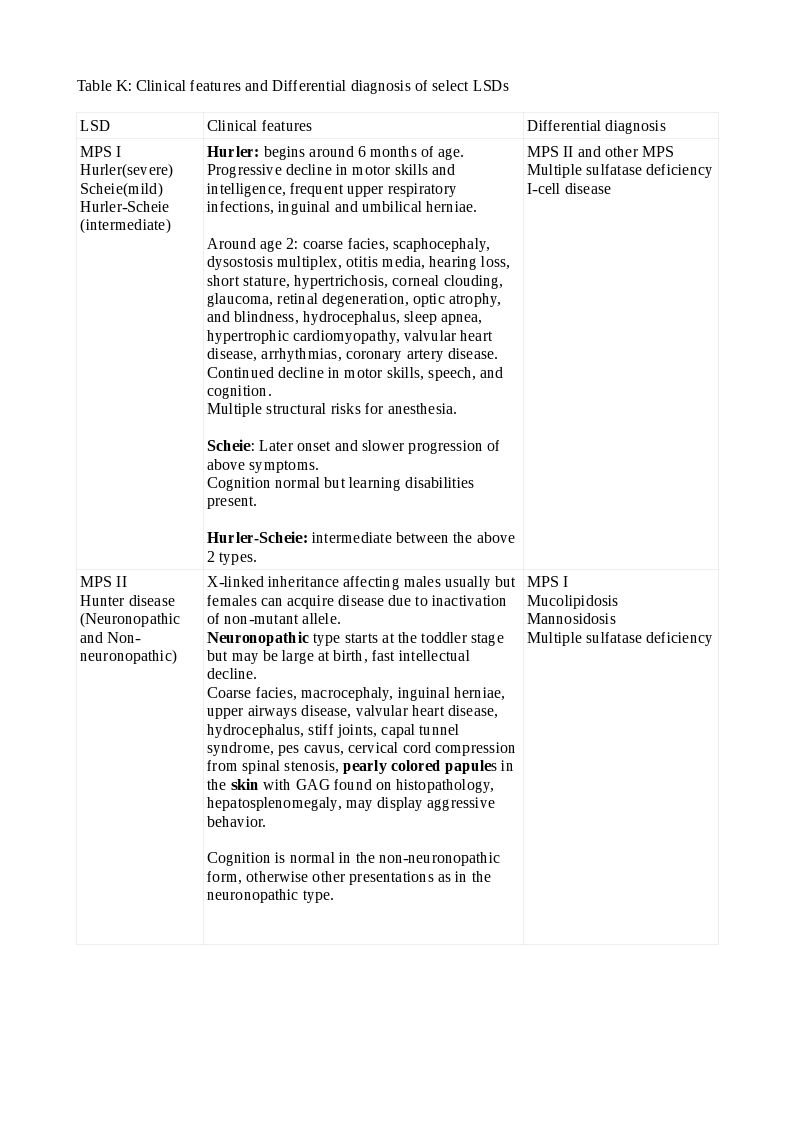

Tables C, D, F, G, H, J, and K depict their clinical features and differential diagnoses.

Evaluation

Clinical suspicion for a particular lysosomal storage disease (LSD) precedes the screening tests. Many LSDs have similar features between themselves and, with other non-lysosomal inborn errors of metabolism and diligence is required. Urine and serum screening tests: Urine GAG elevation points to MPS, an oligosaccharide pattern glycoproteinosis, sialic acid in sialic acid storage disorders, and sulfatide excretion in MLD. A serum CK elevation suggests Pompe disease, while chitotriosidase suggests Gaucher or Niemann-Pick C disease.

The dried blood spot (DBS) specimen that has been so successful in other treatable inborn metabolic errors is useful in diagnosing LSDs. It is especially true in newborn screening programs performed with multiplex assays using mass spectroscopy (MS).[17] The DBS specimen is a convenient and cost-effective method in areas with scarce resources and distant referral laboratories. It is stable during transportation to the reference laboratory.

A positive screen may include many false positives and negatives, which will need confirmation with specific enzyme assays and molecular analyses in serum/plasma, leucocytes from peripheral blood, cultured cell lines like skin fibroblasts and lymphoblasts. Leucocytes have isoenzymes that may cause assay interference. Skin fibroblasts are "gold standard" because of optimum enzyme activity but need a skin biopsy and culture facilities. The cultures, however, can be maintained indefinitely and may be useful in biobanking. Cultured lymphoblasts obtained by Ebstein-Barr virus transformation from a peripheral blood sample is another choice. Still, some enzymes (Arylsulfatase A, for example) are inherently absent and unhelpful in those situations.

Enzyme assays performed with fluorimetric methods are simple to use than the more expensive but fast and accurate liquid chromatography with mass spectroscopy (LC-MS/MS). More and more sophisticated modifications are available and useful in research settings.

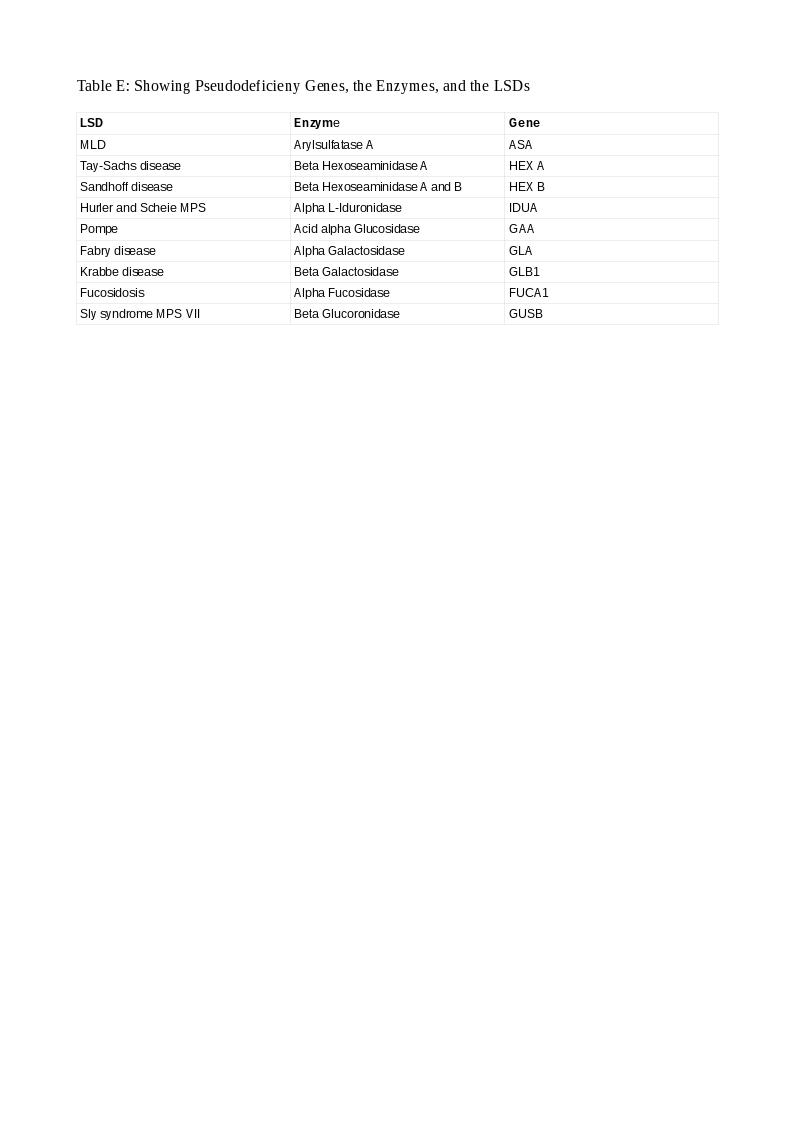

In some situations, a patient has a low enzyme level and normal urinary substrate levels but has no clinical symptoms or signs of the disease. These healthy enzyme deficient persons have a condition called pseudodeficiency. They have between 5 and 15 percent enzyme activity than normals sufficient to metabolize the substrates and prevent their accumulation and explain their health status. Such persons must be recognized promptly to avoid misdiagnosis and its deleterious consequences. They have a mutation in the gene encoding the enzyme in one or both copies forming a pseudoallele gene (Pd). Such Pd patterns are constant in some LSDs and easily recognized and aid in genetic counseling. Pathogenic variants are also characteristic in some LSDs that are easily spotted and action taken. In some LSDs, the Pd is more common than the pathogenic variant (Arylsulfatase A in MLD; 15 versus 1 percent) and, the concept gains much importance. Pseudodeficiency occurs in 9 genes in LSDs. Table E lists these LSDs, the enzymes, and their genes.

Molecular genetic techniques can diagnose mutations in the genes encoding the enzymes. Examples are:

1) Restriction fragment length polymorphism by polymerase chain reaction(RFLP-PCR) 2): Amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS) PCR for detecting point mutations which may be missense, nonsense, splicing, regulatory, small or gross insertions and deletions, or complex ones. Other techniques used are mutation scanning, DNA sequencing, multiplex-PCR, and next-generation sequencing (NGS).[18][19]

The final diagnosis of an LSD should rest on the combined evidence from clinical, biochemical, radiological, and genetic information.

Apart from the tests for the specific diagnosis of the LSD, investigations to address organ damage are necessary. The individual patient's condition dictates these tests. They are:

- X-rays

- MRI scans

- EKG, echocardiogram

- Audiometry, Visual assessment

- Pulmonary function tests

- Hemogram, liver and renal function, and many more.

Many of them may need to be repeated periodically as part of treatment monitoring.

A patient clinically suspected of having an LSD, but with normal enzyme levels and no mutation in the enzyme coding gene should be further investigated. Such patients can have a mutation in the gene for the enzyme activator. A protein called prosaposin (PSAP) has four subunits A, B, C, and D. A gene codes for prosaposin. The code for each subunit occupies separate points on the gene. The prosaposin protein is cleaved into its subunit components. Each subunit functions as an activator protein for a specific enzyme. In the absence of its activator, the normal enzyme is rendered functionless. The substrate accumulates and may leak into the urine; examples are MLD (saposin B) and Gaucher disease (saposin C).[20][21]

Prenatal screening using amniocentesis and chorionic villus biopsy is available for many LSDs. It helps families with an index case that caused fetal or infantile death and helps in genetic counseling.[19]

Newborn screening for LSDs has gained acceptance over the years. It has increased the diagnostic yield many folds, especially of the adult phenotypes. The screen panel has included more LSDs as newer treatments are becoming available.[22]

The application of the principles of both targeted and untargeted metabolomics is an exciting new area that has promise in both the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of LSDs in the future.[23]

Treatment / Management

The treatment of lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) is best undertaken in specialized centers utilizing multiple disciplines under one roof and comprises[24][25][23]:(B3)

1) Enzyme Replacement Therapy (ERT):

Human recombinant enzymes are manufactured in Chinese hamster ovary(CHO) cells using DNA technology. They enhance the metabolism of the accumulated substrate by replacing the deficient/absent enzyme when given intravenously. However, cerliponase is administered via the intraventricular (brain) route for CLN2 lipofuscinosis. Some preparations are tagged to mannose 6-phosphate to target them to the lysosomes. Some enzymes may be co-administered with chaperones to enhance clinical effects.

ERT improves cardiac, and lung function reduces disease burden in the viscera, bone, and improves the blood picture. It can reduce the disease's bio-markers' excretion and improve joint and functional mobility and quality of life. For maximum benefits, ERT works best when started early before organ damage occurs.

ERT is not without disadvantages. It is expensive, time-consuming, and does not penetrate the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) or tissues with poor vascularity. In very young children, the immaturity of some transport systems prevents adequate drug delivery to affected tissues.

To overcome many of these disadvantages, "Next-Generation" ERT is in the pipeline. Modifications to ERT in this modality include:

- Pegylation to increase the half-life

- Antibody tagging to recognize specific receptors and thereby penetrate the BBB

- Direct tissue administration of ERT and,

- Implantation of enzyme-rich capsules into tissues to supply enzyme directly to target and concomitant shielding from antibodies.

- Principles of pharmacogenomics applied to the treatment of LSDs

2) Pharmacological Chaperone Therapy (PCT):

An enzyme in its final form has a tertiary structure. This involves proper folding of the protein molecule that renders it resistant to degradation. A specific mutation in the lysosomal associated protein involved in the folding process renders the enzyme fragile. In such instances, the catalytic site is intact. Small molecules that traverse cellular organelles' membranes and correct the misfolding and render the enzyme resistant to degradation are termed chaperones. When used, they are invaluable in some LSDs.[26]

3) Proteostasis Regulators:

Unlike in PCT, the proteostatic regulators are not ligands (they do not bind to the enzymes) but shift the equilibrium away from protein (enzyme) degradation by controlling several steps in the metabolic pathways. They thus preserve the enzymes. Although an attractive option, they have significant toxicity that precludes their use.

4) Substrate Reduction Therapy (SRT):

Some substances reduce the formation of substrates by inhibiting the enzyme that catalyzes its synthesis. Their onset of action and clinical improvements are slower than ERT. Slowing the progression of neurological symptoms is seen with miglustat in neuropathic LSDs. Other SRTs in clinical trials are genistein, ibiglustat, and lucerastat.[27]

Using antisense oligonucleotides to bind to mRNA of mutant enzymes' genes and reducing the defective protein's formation help reduce substrate accumulation and rescues the physiological enzymes.

5) Small Molecule Assisted Substrate Transportation (SMAST) is a modality where an accumulated substrate, due to a lack of transporter, is converted to another compound that is, transported with ease out of the lysosome.

6) Anti-Inflammatory Agents:

The pathogenesis of LSDs includes inflammation. Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents reduce inflammatory cytokines like IL-1 and TNF-alpha and reduce organ damage.

7) Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT):

Stem cells from donors or umbilical cord blood are used and are fast replacing bone marrow tissue due to ease, rapidity, and increased success. These stem cells can migrate to various organs, including the brain, and differentiate into the cells of the respective tissues and continuously produce the deficient enzyme. They also reduce inflammation and consequent tissue damage. There have been reports of improved visceromegaly and preservation of neurocognitive function. Since engraftment takes time, the neurocognitive function may decline early after HSCT, and ERT acts as a bridge therapy during this period. This ERT-HSCT sequential modality has become the standard of care in some LSDs. Fortunately, ERT does not mitigate the benefits of HSCT in any way. HSCT is FDA approved for MPS I [28]and has shown promise in MLD, alpha mannosidosis, fucosidosis, and aspartylglucosaminuria.

HSCT is suboptimal in reducing the pathology in some tissues like the cornea, heart valves, and the bone. HSCT has been unsuccessful in some LSDs, but one cannot conclude the outcomes due to delays in initiating therapy in these conditions.

8) Gene Therapy:

The autologous ex-vivo method involves harvesting the affected patient's stem cells and introducing the correct version of the gene using viral vectors (lentivirus and retrovirus) into those stem cells in-vitro. This process is called transfection. The next step is bone marrow ablation using chemotherapy. Hematogenous, hepatic, CSF, or direct CNS routes form the final step to re-introduce the corrected cells into the patient.[29][30](B3)

The in-vivo method is the direct transfer of the gene to the tissue that serves as a depot for the viral vectors (adeno-associated virus, AAV).[31](B3)

Much benefit has been demonstrated in clinical trials using this modality and promising therapy in the future.

9) Manipulation of Gene Expression:

In some LSDs, a gene encoding a lysosomal enzyme has a premature termination codon that prematurely stops transcription. It can be overridden by reading through the stop codon using small molecules. It corrects the gene defect and, the unhindered transcription restores the deficient enzyme. This technology has been studied in some degenerative disorders but not in LSDs. It has much promise for the future.

Genome editing delivers the corrected gene version directly to the target organ using several nucleases. It has advantages over gene therapy in that no viral vectors are involved, and the transfer is targeted rather than random.[32] Clinical trials using this modality are in progress.

10) Ancillary Care:

Apart from therapy directed at the defective enzyme, accumulated substrate, and the mutant genes, individual treatments can tackle the complications in the various organ systems that occur in the LSDs. These include:

- Medications for seizures, movement disorders, and psychosis

- Shunts for hydrocephalus

- Special learning skills for children with subnormal intelligence

- Cardiac valvular replacements

- Drugs for heart failure, arrhythmias

- Cardiac pacemakers for rhythm disorders

- Ventilatory support for respiratory failure

- Renal replacement therapy, including transplantation

- Medications for endocrine dysfunction

- Orthopedic braces and corrective surgeries for deformities, fractures

- Speech pathology for swallowing disorders and preventing aspiration

- Vision and ENT issues

- Psychiatry, psychological counseling, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, hospice, and social services.

Table T displays FDA approved ERT, SRT, PCT, and SMAST therapies.

Differential Diagnosis

Lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) have clinical features in common with other LSDs, non-LSD inborn errors of metabolism, and other conditions. Thus, the subtle differences between them should be appreciated and direct the provider to a correct diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for important LSDs are outlined below:

Niemann-Pick A:

GM1 gangliosidosis, Wolman disease, Cholesterol ester storage disease.

Niemann-Pick B:

Niemann-Pick A, Gaucher, Other spingolipidosis.

Niemann-Pick C1 and C2 (perinatal):

Alfa 1 antitrypsin deficiency Tyrosinemia, Idiopathic neonatal cholestasis, Congenital infections, Niemann-Pick A, Gaucher disease.

Niemann-Pick C1 and C2 (Childhood):

GM 2 gangliosidosis, Other LSDs, Organic acidemias, Maple syrup urine disease, Mitochondrial disorders, Wilson Disease, ADHD, Dystonias.

Niemann-Pick C1 and C2 (Adult):

Progressive supranuclear palsy, Alzheimer disease, Frontotemporal dementia, Other psychiatric disorders.

Tay Sachs Disease:

Sandhoff disease, Cerebral Neuronal Lipofuscinosis(CLN), Leigh syndrome, Amyotrophic lateral Sclerosis (ALS).

Sandhoff Disease:

Tay-Sachs, Gaucher, Niemann-Pick, CLN(Juvenile and Adult types), Leigh syndrome.

Gaucher Disease:

Niemann-Pick diseases, Pompe disease, Hurler disease(MPS I), Tay Sachs disease.

Fabry Disease:

Schindler disease, Gaucher disease, Fucosidosis, Erythromelalgia.

Metachromatic leukodystrophy(MLD):

ASA pseudodeficiency, Multiple sulfatase deficiency(MSD), Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy(CIDP), Guillain Barre syndrome(GBS).

Lysosomal Acid Lipase Deficiency (LALD):

Wolman disease, Niemann-Pick diseases, Galactosemia, Fructosemia, Aminoacid metabolism disorder, Chamarin Dorfman syndrome.

Krabbe Disease:

Adrenal leukodystrophy(ALD), MLD, Canavan's leukodystrophy, Alexander disease.

CLN 2 (Late infantile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis 2)/[tripeptyl peptidase 1(TPP1) Deficiency]:

Doose syndrome, Dravet syndrome, Lennox-Gestault syndrome, Lafora disease, , Unverricht-Lundborg disease, Chanelopathies( SCN1A or SCN2A) , CLN 5,6,7,8,10 diseases, Sialidosis, Galactosialidosis,

Grey matter diseases, White matter disease, Mitochondrial diseases, Infections, Intoxications.

Pompe disease(Glycogen Storage Disease II /GSD 2):

Werdnig Hofmann syndrome (Spinal muscular atrophy I), Danon disease, Endomyocardial fibroelastosis, Other GSDs, Fascioscapulohumeral, Becker, and Duchenne muscular dystrophies, McArdle(GSD V), Hers(GSD VI) diseases.

Cystinosis:

Conditions causing Fanconi syndrome, Lowe syndrome, Wilson disease, Tyrosinemia type 1, Galactosemia, GSDs, LSDs, Diabetes Insipidus.

MPS IV A (Morquio A):

MPS IVb, GM 1 gangliosidosis, Other MPS, Mucolipidosis, Legg Calve-Perthes disease, Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia.

MPS VI (Maroteaux-Lamy Syndrome):

MPS I. II, IVa , and VII, Multiple sulfatase deficiency, Mucolipidosis, Sialidosis.

MPS VII(Sly Syndrome):

Other MPS, Mucolipidosis.

MPS I (Hurler (severe), Scheie (mild), Hurler-Scheie (intermediate):

MPS II and other MPS, Multiple sulfatase deficiency, I-cell disease.

MPS II (Hunter disease-Neuronopathic and Non-neuronopathic):

MPS I, Mucolipidosis, Mannosidosis, Multiple sulfatase deficiency.

(also see Tables C, D, F, G, H, J, and K).[33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43]

Prognosis

The prognosis for lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) will depend on:

- Disease phenotype.

- Early diagnosis.

- Specific treatments.

- Facilities for the latest diagnoses and treatment.

In instances with a very severe phenotype, the prognosis is grim. The disease in certain LSDs is complicated by hydrops fetalis or cardiorespiratory failure in the first year of life. Prenatal counseling is of immense help in such cases.

In LSDs, where treatments are available and begun before organ damage sets in, the prognosis improves lifespan and quality of life. Even in such cases, some organ damage is irreversible. Examples are unrelenting neurological dysfunction after HSCT in Hurler disease (MPS I).

As newborn screening becomes universal, and further improvements in diagnostics and treatments occur, the prognosis is likely to get better.

Complications

In lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs), there are two sets of complications:

Those unique to the disease(s). The reader should refer to the clinical features' tables to know in which LSD they occur:

Nervous System

Seizures, hydrocephalus, movement disorders, intellectual disability, psychosis, peripheral neuropathies, carpal tunnel syndrome, and spinal cord compression.

Cardiovascular

Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, hypertension, valvular heart disease, and vasculopathy.

Respiratory

Lung infiltration and damage, sleep apnea, respiratory failure due to lung damage, and kyphoscoliosis.

Gastrointestinal

Splenomegaly and hypersplenism, swallowing difficulties, and increased susceptibility to hepatitis C infection.

Musculoskeletal

Bone lesions, fractures, deformities, joint contractures, atlantoaxial instability, and kyphoscoliosis.

Hematological

Pancytopenia.

Eyes

Corneal opacities and retinal degeneration leading to visual compromise and blindness.

ENT

Adenoids and tonsillar enlargement and their clinical effects, upper respiratory infections, eustachian tube dysfunction, and mixed hearing loss.

Side effects of numerous medications used for adjunct treatment. They include sedatives, antiepileptics, antipsychotics, and many drug interactions.

LSDs patients may need neurosurgical, orthopedic, ENT, ophthalmological, and general surgeries. Anesthetic difficulties are structural anomalies of the cervical spine, jaw, upper airways, and respiratory muscle weakness.

Complications Secondary to Treatments

- ERT in enzyme naive subjects can induce a foreign antigen response and decrease the effectiveness over time.

- Minor, moderate, and severe allergic reactions can also occur and be managed accordingly. These include: slowing or stopping the infusion, adding pre or post medications like antihistamines, steroids, and leukotriene inhibitors.

- Classic anaphylaxis and anaphylactoid reactions may also occur and will need appropriate management.

- Immunomodulator therapy.[44]

- The intraventricular route of administration for some forms of ERT runs the risk of infections.

- HSCT patients may encounter all of the inherent radiation and immunosuppressive therapy complications, including opportunistic infections and graft versus host disease(GVHD).

- Delayed onset of action, need for repeat administration, anti-vector antibodies, and viral neutralizing antibodies are complications of adeno-associated vectors for gene therapy.

Providers should recognize caregiver burnout early and mobilize support.

Consultations

The list of consultations needed to manage lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) include but not limited to,

- Primary care provider (pediatrics, internal medicine, and family medicine)

- Metabolic medicine

- Maternal and fetal medicine

- Cardiology

- Clinical biochemistry

- Clinical pharmacy

- Clinical genetics

- Dermatology

- Gastroenterology

- Neonatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Nursing

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Ophthalmology

- Clinical psychology

- Psychiatry (adult and child)

- Pulmonology

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation

- Speech pathology

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is paramount in the management of lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs). The parents of affected children will need detailed explanations for their child's illness and extensive counseling to help them adapt and cope with a child suffering from a lifelong chronic condition. They should be encouraged to utilize appropriate resources like support groups and foundations dedicated to a particular disease condition. They will need to know that newer treatments are available and will need guidance to referral centers that undertake those treatments. Education on the inheritance pattern in future generations will allay fears and help plan and manage complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) are rare inborn errors of metabolism. Defective lysosomal enzymes are the chief cause. Other causes include defects in lysosomal enzyme activator, lysosomal membrane proteins, or non-lysosomal proteins.

- They are rare individually, some very rare, but they are much more common as a group.

- The lysosome is no longer the waste recycle-bin of the cell, and subsequent research has shown it has far-reaching roles in cellular metabolism and energy generation.

- The study of this organelle has paved the way for understanding how LSDs affect different organs and the methods to investigate and treat them.

- LSDs presenting early in fetal life, infancy, or childhood are usually severe, while a late-onset disease in adults is mild.

- Organ involvement varies with age; the brain's effects are more profound in the younger age group.

- The substrates accumulate within cells because of a lack of a specific enzyme and cause organ dysfunction.

- The earlier the onset, the more severe the dysfunction.

- There are specific clinical characteristics for the individual LSDs that provide the lead to the diagnosis.

- The first investigation is usually the enzyme levels that are either deficient(mild disease) or absent(severe disease).

- Pseudodeficiency may complicate certain LSDs.

- Genetic testing for the mutated genes coding for those enzymes is available and can confirm the enzyme tests.

- A low enzyme level with appropriate clinical suspicion and the normal gene encoding the enzyme should prompt a search for mutations in the genes for enzyme activator proteins.

- Genetic tests are useful in cases of mild disease when the enzyme tests are borderline.

- Genetic testing is also helpful in detecting carriers and helps in family counseling.

- The prognosis was dismal in the past, but the advent of modern therapy like ERT, HSCT, SRT, VAGT, and SCT has vastly improved lifespan and quality.

- The treatment started early before organ damage sets in will result in maximum benefits from these therapies.

- Newborn-screening programs have been devised and tested, and maybe the answer to detect LSDs early and gain maximum therapeutic advantage from modern treatment techniques.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) though rare individually are common, as a group. The pediatrician is often the primary care provider (PCP) to see the patient. The PCP will have clues to observe at birth, during infancy, and childhood, leading to the suspicion of LSDs as the likely cause. Sometimes a specialist or sub-specialist may diagnose the condition which testifies as to the multi-faceted presentations of LSDs.[45] The suspicion of LSDs made clinically should automatically lead to a referral to a consultant in Genetics or pediatric endocrinologist specializing in metabolic diseases and will need a detailed history and family pedigree to make an accurate diagnosis.

The clinical biochemist who performs the enzyme assay will similarly need all the information, and so too the radiologist. Likewise, different specialists will be involved in the care of some aspect of the child's illness and coordinated care, and efficient interprofessional communication is vital to good outcomes. Allied health professionals like nurses, physiotherapists, and clinical psychologists play a significant role in patient education and care. Pharmacists are crucial to monitor ERT and SRT.

LSDs are classic examples in healthcare where dedicated centers with multi-disciplinary specialist groups see the patient together on the same premises, discuss their findings, and arrive at a consensus on management's next step. It helps prevent delays, decreases patients lost to follow-up, and vastly improve outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Platt FM, d'Azzo A, Davidson BL, Neufeld EF, Tifft CJ. Lysosomal storage diseases. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2018 Oct 1:4(1):27. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0025-4. Epub 2018 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 30275469]

Ysselstein D, Shulman JM, Krainc D. Emerging links between pediatric lysosomal storage diseases and adult parkinsonism. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2019 May:34(5):614-624. doi: 10.1002/mds.27631. Epub 2019 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 30726573]

Donida B, Jacques CED, Mescka CP, Rodrigues DGB, Marchetti DP, Ribas G, Giugliani R, Vargas CR. Oxidative damage and redox in Lysosomal Storage Disorders: Biochemical markers. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2017 Mar:466():46-53. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.01.007. Epub 2017 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 28082023]

Schultz ML, Tecedor L, Chang M, Davidson BL. Clarifying lysosomal storage diseases. Trends in neurosciences. 2011 Aug:34(8):401-10. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.05.006. Epub 2011 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 21723623]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStirnemann J, Belmatoug N, Camou F, Serratrice C, Froissart R, Caillaud C, Levade T, Astudillo L, Serratrice J, Brassier A, Rose C, Billette de Villemeur T, Berger MG. A Review of Gaucher Disease Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation and Treatments. International journal of molecular sciences. 2017 Feb 17:18(2):. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020441. Epub 2017 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 28218669]

Wasserstein MP, Caggana M, Bailey SM, Desnick RJ, Edelmann L, Estrella L, Holzman I, Kelly NR, Kornreich R, Kupchik SG, Martin M, Nafday SM, Wasserman R, Yang A, Yu C, Orsini JJ. The New York pilot newborn screening program for lysosomal storage diseases: Report of the First 65,000 Infants. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2019 Mar:21(3):631-640. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0129-y. Epub 2018 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 30093709]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHopkins PV, Klug T, Vermette L, Raburn-Miller J, Kiesling J, Rogers S. Incidence of 4 Lysosomal Storage Disorders From 4 Years of Newborn Screening. JAMA pediatrics. 2018 Jul 1:172(7):696-697. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0263. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29813145]

Mehta A, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G, Fuller M, Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ. Epidemiology of lysosomal storage diseases: an overview. Fabry Disease: Perspectives from 5 Years of FOS. 2006:(): [PubMed PMID: 21290699]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParkinson-Lawrence EJ, Shandala T, Prodoehl M, Plew R, Borlace GN, Brooks DA. Lysosomal storage disease: revealing lysosomal function and physiology. Physiology (Bethesda, Md.). 2010 Apr:25(2):102-15. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20430954]

Xu H,Ren D, Lysosomal physiology. Annual review of physiology. 2015; [PubMed PMID: 25668017]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnnunziata I, Sano R, d'Azzo A. Mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) and lysosomal storage diseases. Cell death & disease. 2018 Feb 28:9(3):328. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0025-4. Epub 2018 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 29491402]

Ballabio A, Bonifacino JS. Lysosomes as dynamic regulators of cell and organismal homeostasis. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2020 Feb:21(2):101-118. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0185-4. Epub 2019 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 31768005]

Hsu VW, Lee SY, Yang JS. The evolving understanding of COPI vesicle formation. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2009 May:10(5):360-4. doi: 10.1038/nrm2663. Epub 2009 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 19293819]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePlatt FM, Boland B, van der Spoel AC. The cell biology of disease: lysosomal storage disorders: the cellular impact of lysosomal dysfunction. The Journal of cell biology. 2012 Nov 26:199(5):723-34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201208152. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23185029]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOyarzún JE, Lagos J, Vázquez MC, Valls C, De la Fuente C, Yuseff MI, Alvarez AR, Zanlungo S. Lysosome motility and distribution: Relevance in health and disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular basis of disease. 2019 Jun 1:1865(6):1076-1087. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.03.009. Epub 2019 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 30904612]

Finkbeiner S. The Autophagy Lysosomal Pathway and Neurodegeneration. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2020 Mar 2:12(3):. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a033993. Epub 2020 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 30936119]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElliott S, Buroker N, Cournoyer JJ, Potier AM, Trometer JD, Elbin C, Schermer MJ, Kantola J, Boyce A, Turecek F, Gelb MH, Scott CR. Pilot study of newborn screening for six lysosomal storage diseases using Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2016 Aug:118(4):304-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2016.05.015. Epub 2016 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 27238910]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMokhtariye A, Hagh-Nazari L, Varasteh AR, Keyfi F. Diagnostic methods for Lysosomal Storage Disease. Reports of biochemistry & molecular biology. 2019 Jan:7(2):119-128 [PubMed PMID: 30805390]

Filocamo M, Morrone A. Lysosomal storage disorders: molecular basis and laboratory testing. Human genomics. 2011 Mar:5(3):156-69 [PubMed PMID: 21504867]

Tamargo RJ, Velayati A, Goldin E, Sidransky E. The role of saposin C in Gaucher disease. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2012 Jul:106(3):257-63. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.04.024. Epub 2012 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 22652185]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCesani M, Lorioli L, Grossi S, Amico G, Fumagalli F, Spiga I, Filocamo M, Biffi A. Mutation Update of ARSA and PSAP Genes Causing Metachromatic Leukodystrophy. Human mutation. 2016 Jan:37(1):16-27. doi: 10.1002/humu.22919. Epub 2015 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 26462614]

Schielen PCJI, Kemper EA, Gelb MH. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Diseases: A Concise Review of the Literature on Screening Methods, Therapeutic Possibilities and Regional Programs. International journal of neonatal screening. 2017 Jun:3(2):. pii: 6. doi: 10.3390/ijns3020006. Epub 2017 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 28730181]

Pinto E Vairo F, Rojas Málaga D, Kubaski F, Fischinger Moura de Souza C, de Oliveira Poswar F, Baldo G, Giugliani R. Precision Medicine for Lysosomal Disorders. Biomolecules. 2020 Jul 26:10(8):. doi: 10.3390/biom10081110. Epub 2020 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 32722587]

Beck M. Treatment strategies for lysosomal storage disorders. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2018 Jan:60(1):13-18. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13600. Epub 2017 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 29090451]

Thomas R, Kermode AR. Enzyme enhancement therapeutics for lysosomal storage diseases: Current status and perspective. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2019 Feb:126(2):83-97. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.11.011. Epub 2018 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 30528228]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHilz MJ, Arbustini E, Dagna L, Gasbarrini A, Goizet C, Lacombe D, Liguori R, Manna R, Politei J, Spada M, Burlina A. Non-specific gastrointestinal features: Could it be Fabry disease? Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2018 May:50(5):429-437. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2018.02.011. Epub 2018 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 29602572]

Coutinho MF, Santos JI, Alves S. Less Is More: Substrate Reduction Therapy for Lysosomal Storage Disorders. International journal of molecular sciences. 2016 Jul 4:17(7):. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071065. Epub 2016 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 27384562]

Barth AL, de Magalhães TSPC, Reis ABR, de Oliveira ML, Scalco FB, Cavalcanti NC, Silva DSE, Torres DA, Costa AAP, Bonfim C, Giugliani R, Llerena JC Jr, Horovitz DDG. Early hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in a patient with severe mucopolysaccharidosis II: A 7 years follow-up. Molecular genetics and metabolism reports. 2017 Sep:12():62-68. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2017.05.010. Epub 2017 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 28649514]

Nagree MS, Scalia S, McKillop WM, Medin JA. An update on gene therapy for lysosomal storage disorders. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2019 Jul:19(7):655-670. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2019.1607837. Epub 2019 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 31056978]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCachon-Gonzalez MB, Zaccariotto E, Cox TM. Genetics and Therapies for GM2 Gangliosidosis. Current gene therapy. 2018:18(2):68-89. doi: 10.2174/1566523218666180404162622. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29618308]

Penati R, Fumagalli F, Calbi V, Bernardo ME, Aiuti A. Gene therapy for lysosomal storage disorders: recent advances for metachromatic leukodystrophy and mucopolysaccaridosis I. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2017 Jul:40(4):543-554. doi: 10.1007/s10545-017-0052-4. Epub 2017 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 28560469]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchneller JL, Lee CM, Bao G, Venditti CP. Genome editing for inborn errors of metabolism: advancing towards the clinic. BMC medicine. 2017 Feb 27:15(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0798-4. Epub 2017 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 28238287]

Chan B, Adam DN. A Review of Fabry Disease. Skin therapy letter. 2018 Mar:23(2):4-6 [PubMed PMID: 29562089]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElmonem MA, Veys KR, Soliman NA, van Dyck M, van den Heuvel LP, Levtchenko E. Cystinosis: a review. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2016 Apr 22:11():47. doi: 10.1186/s13023-016-0426-y. Epub 2016 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 27102039]

Dandana A, Ben Khelifa S, Chahed H, Miled A, Ferchichi S. Gaucher Disease: Clinical, Biological and Therapeutic Aspects. Pathobiology : journal of immunopathology, molecular and cellular biology. 2016:83(1):13-23. doi: 10.1159/000440865. Epub 2015 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 26588331]

McCall AL, ElMallah MK. Macroglossia, Motor Neuron Pathology, and Airway Malacia Contribute to Respiratory Insufficiency in Pompe Disease: A Commentary on Molecular Pathways and Respiratory Involvement in Lysosomal Storage Diseases. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 Feb 11:20(3):. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030751. Epub 2019 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 30754627]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArends M, Wanner C, Hughes D, Mehta A, Oder D, Watkinson OT, Elliott PM, Linthorst GE, Wijburg FA, Biegstraaten M, Hollak CE. Characterization of Classical and Nonclassical Fabry Disease: A Multicenter Study. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2017 May:28(5):1631-1641. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016090964. Epub 2016 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 27979989]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceColmenares-Bonilla D, Colin-Gonzalez C, Gonzalez-Segoviano A, Esquivel Garcia E, Vela-Huerta MM, Lopez-Gomez FG. Diagnosis of Mucopolysaccharidosis Based on History and Clinical Features: Evidence from the Bajio Region of Mexico. Cureus. 2018 Nov 20:10(11):e3617. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3617. Epub 2018 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 30705788]

Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, Gomez-Ospina N. Arylsulfatase A Deficiency. GeneReviews(®). 1993:(): [PubMed PMID: 20301309]

Specchio N, Pietrafusa N, Trivisano M. Changing Times for CLN2 Disease: The Era of Enzyme Replacement Therapy. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2020:16():213-222. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S241048. Epub 2020 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 32280231]

Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, Hoffman EP, Barr ML, Giovanni MA, Murray MF. Lysosomal Acid Lipase Deficiency. GeneReviews(®). 1993:(): [PubMed PMID: 26225414]

Patterson MC, Clayton P, Gissen P, Anheim M, Bauer P, Bonnot O, Dardis A, Dionisi-Vici C, Klünemann HH, Latour P, Lourenço CM, Ory DS, Parker A, Pocoví M, Strupp M, Vanier MT, Walterfang M, Marquardt T. Recommendations for the detection and diagnosis of Niemann-Pick disease type C: An update. Neurology. Clinical practice. 2017 Dec:7(6):499-511. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000399. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29431164]

Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, Orsini JJ, Escolar ML, Wasserstein MP, Caggana M. Krabbe Disease. GeneReviews(®). 1993:(): [PubMed PMID: 20301416]

Kishnani PS, Dickson PI, Muldowney L, Lee JJ, Rosenberg A, Abichandani R, Bluestone JA, Burton BK, Dewey M, Freitas A, Gavin D, Griebel D, Hogan M, Holland S, Tanpaiboon P, Turka LA, Utz JJ, Wang YM, Whitley CB, Kazi ZB, Pariser AR. Immune response to enzyme replacement therapies in lysosomal storage diseases and the role of immune tolerance induction. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2016 Feb:117(2):66-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.11.001. Epub 2015 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 26597321]

Del Longo A, Piozzi E, Schweizer F. Ocular features in mucopolysaccharidosis: diagnosis and treatment. Italian journal of pediatrics. 2018 Nov 16:44(Suppl 2):125. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0559-9. Epub 2018 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 30442167]