Introduction

Retropharyngeal abscesses are rare but potentially life-threatening infections that primarily affect children of age 5 and younger and, occasionally, adults. Retropharyngeal abscesses are pus-filled collections within the retropharyngeal space, located between the buccopharyngeal fascia anteriorly and the alar fascia posteriorly. In younger pediatric patients, antecedent upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) commonly lead to suppurative cervical lymphadenitis and retropharyngeal abscesses. Conversely, in older children and adults, retropharyngeal abscesses can be triggered by trauma to the posterior pharynx, leading to the inoculation of the retropharyngeal space and subsequent abscess formation. Although a viral URI typically precedes abscess formation, retropharyngeal infections may also arise from oropharyngeal trauma or dental disease.

Primary infections of tonsils and teeth can potentially progress to retropharyngeal abscesses, although they more commonly lead to peritonsillar abscess (quinsy) or parapharyngeal abscess, respectively. Direct expansion from spinal discitis or osteomyelitis is a rare cause of retropharyngeal abscess and can be considered a complication.[1][2] As a retropharyngeal abscess enlarges, it can result in upper airway obstruction and potentially lead to asphyxiation.

Untreated retropharyngeal abscesses can result in upper airway obstruction and respiratory distress. Treatment of retropharyngeal abscesses involves the administration of prolonged courses of broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics, with or without surgical incision and drainage.[3][4][5] Patients diagnosed with retropharyngeal infection may also necessitate hospital admission and consultation with otolaryngology. Following infection resolution, some patients may require extended hospitalization, tracheostomy, and/or nasogastric tube feeding due to prolonged inflammation in the upper aerodigestive tract.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

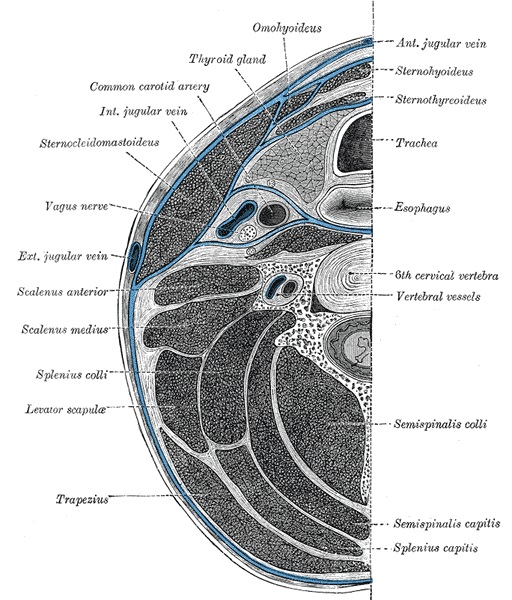

Understanding the fascial layers of the neck is critical to understanding the etiopathogenesis of retropharyngeal abscesses. The neck contains 2 cervical fasciae—superficial and deep—with the deep cervical fascia further segmented into superficial, middle, and deep layers. The superficial cervical fascia envelops the platysma muscle, superficial neurovascular structures (such as the external jugular vein and great auricular nerve), superficial lymphatics, and superficial cervical fat (see Image. Deep Cervical Fascia of the Neck).

The superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia invests in the sternocleidomastoid, anterior digastric, and trapezius muscles, as well as the submandibular glands. Superiorly, it merges with the parotidomasseteric and deep temporal fasciae. This fascia extends downward to the level of the clavicles. The middle layer of the deep cervical fascia comprises a muscular division, which surrounds the strap muscles, and a visceral division, which encloses the pharyngeal constrictor muscles, the larynx, the trachea, and the thyroid gland. The buccopharyngeal fascia constitutes the posterior aspect of the visceral division and forms the anterior border of the retropharyngeal space.

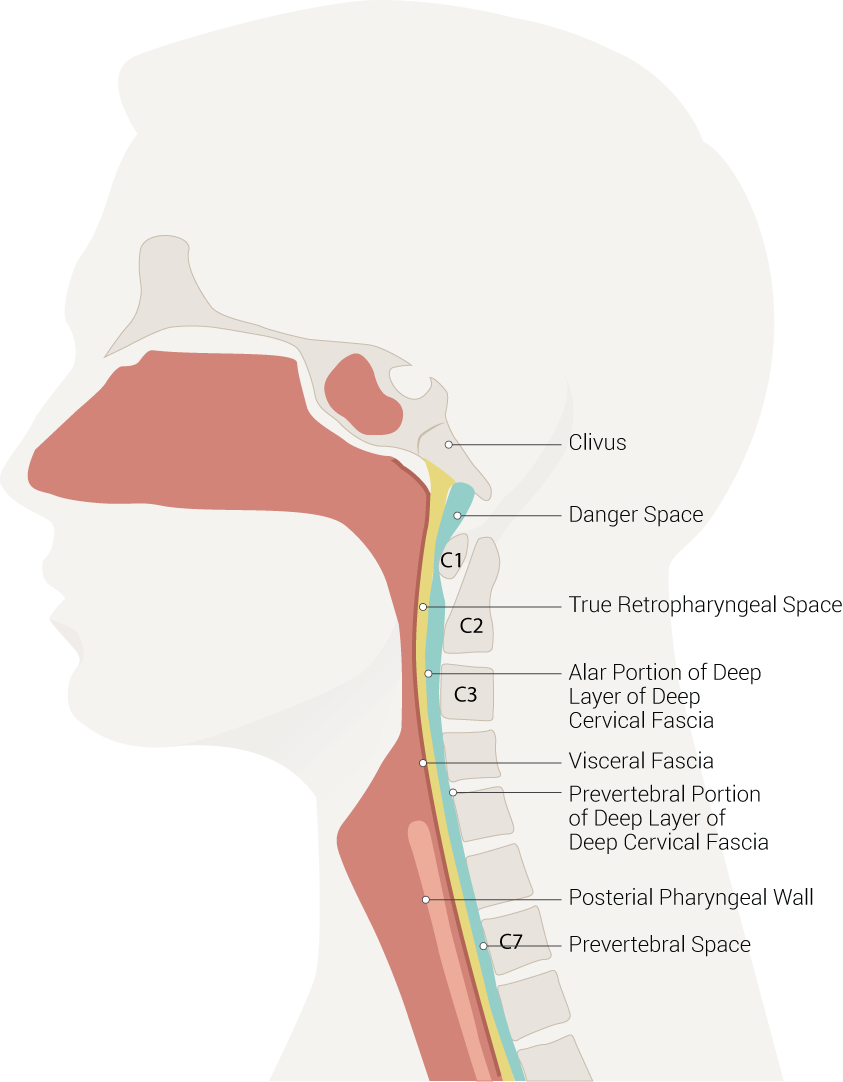

The retropharyngeal space descends to the posterior mediastinum, approximately reaching the level of the tracheal bifurcation. At this point, the buccopharyngeal fascia merges with the alar division of the deep layer of the deep cervical fascia. The deep layer of the deep cervical fascia comprises the alar and prevertebral divisions, with the alar division situated between the visceral division of the middle layer of the deep cervical fascia and the prevertebral division of the deep layer of the deep cervical fascia. The prevertebral division is adherent to the vertebral bodies. Between the prevertebral and alar divisions lies the "danger space," which extends to the level of the diaphragm. Between the prevertebral layer and the vertebral bodies lies the prevertebral space, which extends down to the coccyx (see Image. Neck Spaces Pertinent to Retropharyngeal Abscess).

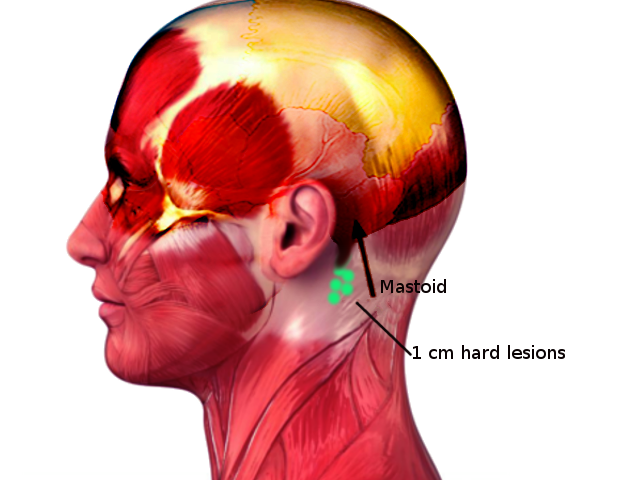

A retropharyngeal abscess is a suppurative collection within the retropharyngeal space. Infections of the prevertebral and danger spaces are also possible but are less common, with the potential to extend further inferiorly than a retropharyngeal abscess. Within the retropharyngeal space, lymph node chains exist that are responsible for draining the nasopharynx, adenoids, posterior paranasal sinuses, and middle ear. These lymph node chains are present in young children, but they typically undergo atrophy and become involute by age 4 to 5. In one-half of cases of retropharyngeal abscess, patients report an antecedent URI. Such infections lead to suppurative adenitis of these retropharyngeal lymph nodes, culminating in abscess formation (see Image. Lymph Nodes of the Retropharyngeal Space).

In adults and older children, trauma to the posterior pharynx often serves as the primary cause of retropharyngeal abscesses, leading to subsequent infection and abscess formation. One-quarter of retropharyngeal abscesses are attributed to the trauma of the posterior pharynx, resulting in inoculation of the retropharyngeal space with bacteria, cellulitis, phlegm formation, and, eventually, retropharyngeal abscess.[6][7][8] Risk factors associated with retropharyngeal space infections include poor oral hygiene, diabetes, immunocompromised states, and low socioeconomic status.

Epidemiology

Although retropharyngeal abscesses can occur at any age, they typically manifest in children aged between 2 and 4. A male predominance is seen at 53% to 55% of infections.[9] Half of retropharyngeal abscesses result from antecedent URI, leading to retropharyngeal suppurative lymphadenitis and eventual abscess formation.[10] One-quarter of cases result from retropharyngeal trauma, which results in the inoculation of the retropharyngeal space with bacteria and subsequent abscess formation. Although uncommon, data from 2000 through 2009 indicate an increasing incidence of retropharyngeal abscesses.[3][11]

Pathophysiology

In children aged 5 and younger, the retropharyngeal space hosts chains of lymph nodes responsible for draining the nasopharynx, adenoids, posterior paranasal sinuses, and middle ear. A URI can lead to suppurative adenitis of these retropharyngeal lymph nodes, subsequently resulting in abscess formation. Retropharyngeal lymph nodes undergo atrophy and involution as part of normal development, reducing the likelihood of URI-induced retropharyngeal abscesses. Conversely, in older children and adults, trauma to the posterior pharynx frequently precipitates retropharyngeal infection, serving as a common cause of abscess formation.

After suppurative adenitis or trauma resulting in the seeding of the retropharyngeal space, cellulitis develops and eventually leads to phlegmon and abscess formation. Retropharyngeal abscesses frequently involve polymicrobial infections, with commonly isolated bacteria including Group A Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Fusobacterium and Haemophilus, and other respiratory anaerobic organisms. As the retropharyngeal abscess grows, it results in gradual upper airway obstruction and potentially asphyxiation if untreated. Although mortality from sepsis can occur in these patients, the primary cause of death in patients with retropharyngeal abscess remains upper airway obstruction and respiratory distress.[12][13]

History and Physical

Early retropharyngeal abscess may resemble uncomplicated pharyngitis. Suspicion for the presence of a retropharyngeal abscess should be raised if there is a history of antecedent URIs or trauma to the posterior pharynx. As a retropharyngeal infection advances, symptoms of upper aerodigestive tract obstruction become increasingly evident, usually worsening over several days.

The red flags in a patient's history that should raise concern for upper aerodigestive tract obstruction include dysphagia, odynophagia, inability to tolerate oral secretions, neck stiffness, torticollis, refusal to extend neck due to pain or discomfort, change in voice ("hot potato" or hypernasal voice and muffled voice), trismus, neck swelling, cervical lymphadenopathy, chest pain (due to mediastinal involvement), and respiratory distress (stridor, tachypnea, and retractions).

Patients presenting with retropharyngeal abscesses are typically febrile and appear unwell. In the early stages of the illness, they may exhibit only mild-to-moderate pharyngeal erythema and have difficulty tolerating oral intake. Pharyngeal erythema and swelling become more pronounced as the infection advances, making oral secretion management challenging. Patients often experience significant discomfort with neck extension and frequently opt to keep their necks in flexion, unlike in epiglottitis, where patients prefer neck extension.

Examination of the oropharynx in a patient suspected of having a retropharyngeal abscess should be conducted cautiously, preferably by clinicians experienced in emergent airway management, using palpation or probing techniques. There is a risk of abscess rupture during posterior pharynx examination, which could result in aspiration and potential pneumonitis. The oropharyngeal examination should be performed with patients in the Trendelenburg position to minimize the risk of aspiration in the event of abscess rupture, and suction equipment should be readily available. During examination, the posterior oropharyngeal wall may exhibit bulging at the level of the abscess, although this bulge may not be visible if the abscess is located below the level of the tongue base. The palate is typically not edematous, and unilateral tonsillar exudate is rare. Moreover, tonsillar medialization or trismus findings are uncommon in retropharyngeal abscesses but are more commonly observed in peritonsillar abscesses.

Evaluation

Laboratory tests, including a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein level, and blood cultures, are necessary if a retropharyngeal abscess is suspected. However, the collection of these labs should be postponed if phlebotomy causes additional distress to the patient. Heightened anxiety can exacerbate early upper airway obstruction, potentially leading to respiratory decompensation, especially in younger children. Importantly, it is necessary to obtain both aerobic and anaerobic blood cultures. In patients with retropharyngeal abscesses, white blood cell counts are typically greater than 12,000/μL in 91% of cases.[5][14][15]

Lateral neck radiographs are the preferred imaging modality for the initial evaluation of suspected retropharyngeal abscesses, particularly in young children. This choice is due to their lower radiation exposure and better patient tolerance, especially those showing signs of airway compromise. Lateral neck x-rays should be obtained during inspiration, with the neck in normal extension. Improper positioning during image acquisition can lead to a false-positive interpretation of the study. In the presence of a retropharyngeal infection, the lateral neck x-ray may show an increased thickness of the prevertebral space (see Image. Retropharyngeal Abscess on X-ray Imaging).

In healthy children, the upper limit of normal for the thickness of the prevertebral soft tissue is 7 mm at C2 and 14 mm at C6. In healthy adults, the upper limit of normal for the thickness of the prevertebral soft tissue is 7 mm at C2 and 2 mm at C6. A width of 20 mm at C6 indicates abscess collection. Alternatively, a soft tissue width greater than half the width of the adjacent vertebral body from C1 to C4 or greater than that of the adjacent vertebral body from C5 to C7 also suggests retropharyngeal infection. An air-fluid level or loss of normal cervical lordosis may also indicate retropharyngeal infection. The sensitivity and specificity of the lateral neck plain film for identifying retropharyngeal abscess are 80% and 100%, respectively.[16] Furthermore, patients presenting with a concerning history of retropharyngeal abscess and complaining of chest pain should undergo a chest x-ray to assess for potential mediastinal involvement.

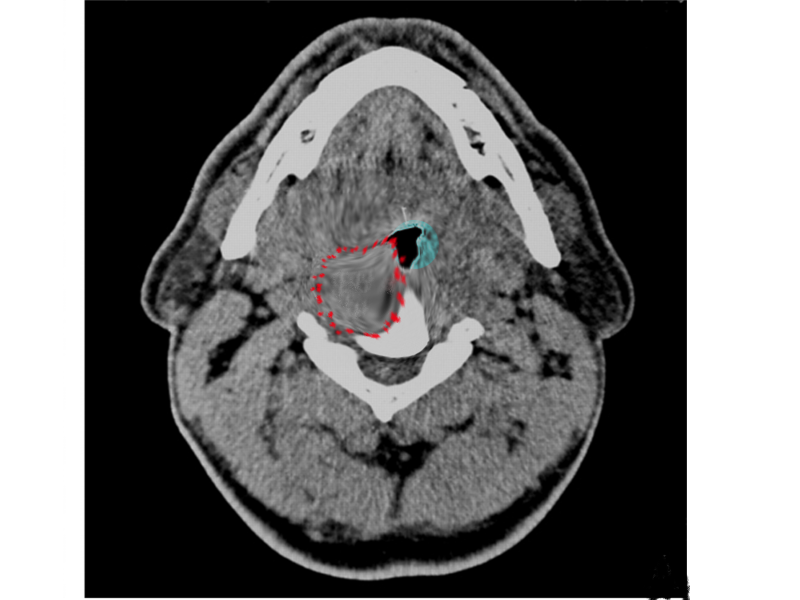

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck with IV contrast is the gold standard imaging modality to evaluate patients with suspected retropharyngeal abscesses (see Image. Retropharyngeal Abscess on CT Imaging). If there is concern for airway compromise in these patients, a clinician trained in emergency airway management should be present during the CT scan. Patients may require emergent surgical airway placement if upper airway obstruction occurs. The sensitivity and specificity of CT scanning for detecting retropharyngeal abscesses are 100% and 45%, respectively.[16]

In children, ultrasound is preferred over CT scanning due to its radiation-free nature and portability, allowing it to be brought to the examination room. In experienced hands, ultrasound can detect the presence of a retropharyngeal abscess with 89% sensitivity and 100% specificity, appearing to outperform CT in distinguishing between infections that are abscesses and those that are not.[17][18] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be considered in cases of cellulitis (see Image. Retropharyngeal Cellulitis on MRI Imaging).

Treatment / Management

Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of retropharyngeal infection should be admitted to the hospital and receive IV antibiotics, along with consultation from otolaryngology. Antibiotic therapy should target upper respiratory organisms, including anaerobic organisms. Those presenting with airway compromise require immediate surgical incision and drainage to alleviate the obstruction.[19][20][21] Management of the condition typically initiates with a 24- to 48-hour trial of IV antibiotic therapy in patients who do not present with severe respiratory distress or airway compromise. Following 24 to 48 hours of antibiotic therapy, an otolaryngologist should reassess the need for surgical incision and drainage.(B3)

Factors associated with an increased requirement for surgical intervention include a cross-sectional area greater than 2 cm2 and symptoms persisting for more than 2 days. No evidence indicates that patients with mature abscesses greater than 3 cm2 benefit from surgical intervention before completing 24 to 48 hours of antibiotic therapy. All patients undergoing treatment for retropharyngeal abscess must undergo meticulous airway monitoring, particularly during the initial 24 to 48 hours of treatment.

Initial antibiotic therapy should include either ampicillin-sulbactam (50 mg/kg every 6 hours) or clindamycin (15 mg/kg every 8 hours). In cases where patients exhibit signs of sepsis or are unresponsive to initial antibiotic therapy, vancomycin or linezolid may also be administered. Parenteral antibiotics should be continued until patients show clinical improvement and remain afebrile for at least 24 hours. After patients demonstrate improvement and remain afebrile, they may be transitioned to oral antibiotics. Amoxicillin-clavulanate (45 mg/kg every 12 hours) or clindamycin (13 mg/kg every 8 hours) are suitable oral regimens. Oral antibiotics should be prescribed for 14 days, and the patient may be discharged home with strict return precautions.

Surgical intervention should be strongly considered if symptoms fail to improve after 24 to 48 hours of antibiotic therapy or if the abscess exceeds 2 to 2.5 cm.[22][23] Intraoral access under general anesthesia is preferred due to the ease of incising and draining the abscess, particularly without the need for a skin incision. Once the mouth is opened, a vertical incision directly overlies the abscess using a McIvor or Crowe-Davis mouth gag. A culture is obtained, and copious irrigation and suction are utilized to evacuate the abscess contents.(B3)

Intraoral access poses significant challenges for abscesses situated below the level of C3, making a transcervical approach potentially more effective. Complication rates are comparable between the 2 approaches, although patients undergoing transcervical drainage typically experience a more extended hospital stay.[24] The incision used for the transcervical approach is generally made along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and blunt dissection is carried toward the abscess to prevent injury to critical cervical neurovascular structures (see Image. The Transcervical Approach to Retropharyngeal Abscess).

Differential Diagnosis

The conditions that are considered in the differential diagnosis of retropharyngeal abscess include airway foreign body,[25] pneumonia,[26] mediastinitis,[27] parapharyngeal abscess,[28] peritonsillar abscess,[29] odontogenic infection or abscess,[30] sialadenitis,[31][32] epiglottitis,[33] pharyngitis,[34] Ludwig angina,[35] and Lemierre syndrome.[36]

Prognosis

When diagnosed early and treated promptly, the prognosis for retropharyngeal abscesses is generally favorable, with mortality rates of up to 2.6% in adults and potentially lower in children.[37][38] However, aggressive treatment is often necessary, usually requiring management in the intensive care unit (ICU). Delays in diagnosis and treatment can lead to the development of serious complications, significantly raising the risk of morbidity and mortality.[4][39]

Complications

Complications of retropharyngeal abscesses include airway obstruction, bronchial erosion, mediastinitis, sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cranial nerve palsies, esophageal perforation, erosion into the carotid artery or jugular vein, and meningoencephalitis.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

After surgery, patients should remain NPO (nil per os, nothing by mouth) until all signs of the abscess have subsided. In an ICU setting, patients require vigilant monitoring for potential airway complications. If there are any indications of airway edema following an abscess drainage procedure, intubation should be considered for 24 to 48 hours postoperatively. Broad-spectrum IV antibiotics are initiated initially, and alternative enteral feeding methods may be necessary. Once patients have stabilized, they may be transitioned to culture-directed oral antibiotics.

Consultations

The consultations recommended for retropharyngeal abscesses include otolaryngology, dentistry, anesthesia, critical care, pediatrics, and infectious disease.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Although it may be challenging to prevent the antecedent URIs or oropharyngeal trauma leading to retropharyngeal abscesses, measures such as wearing masks and practicing hand hygiene can help. In addition, dental infections can be prevented by maintaining good oral hygiene and undergoing routine dental examinations.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A retropharyngeal abscess is a severe infection that can pose a threat to life by obstructing the airway, potentially leading to fatal outcomes. Due to the high risk of morbidity and mortality, a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals must collaborate in diagnosing and managing the condition.

The interprofessional healthcare team should perform the following roles to manage retropharyngeal abscesses:

- Triage nurses should be familiar with the symptoms of retropharyngeal abscess and other deep neck space infections, ensuring they do not mistake their presentation for a viral URI. Patients showing signs of toxicity should be promptly admitted, and the emergency department clinician should be notified accordingly.

- Clinicians in the emergency department should refrain from performing an oropharyngeal examination in patients experiencing respiratory distress to prevent potential irritation of the upper aerodigestive tract and respiratory decompensation. In cases of toxicity, immediate notification of the otolaryngologist and anesthesiologist is essential if an emergency airway intervention is necessary.

- A radiologist should be consulted to determine the appropriate imaging modalities for identifying the location and extent of the abscess.

- An otolaryngologist and a critical care specialist should provide pre- and postoperative monitoring for the patient.

- Nursing staff should closely monitor the patient's vital signs, oxygenation, and ventilation. Any deviation from normal parameters should be immediately communicated to the multidisciplinary healthcare team due to the high risk of airway compromise. In addition, nurses play a crucial role in educating both the patient and their families about the recovery process.

- A dietician should be consulted to determine if parenteral or nasogastric feeding is necessary for patients who are unable to eat for an extended period, even after the resolution of the infection.

- Patients who have undergone a tracheostomy may necessitate respiratory therapy follow-up to receive instruction on tracheal care, weaning, and decannulation.

Maintaining good oral hygiene and receiving preventive dental care can aid in preventing retropharyngeal abscesses. Any difficulty swallowing or breathing, along with fever, warrants immediate medical attention. Notably, it is crucial not to mistake bacterial deep neck space infections for a typical URI.[40][41][42]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Neck Spaces Pertinent to Retropharyngeal Abscess. The illustration of neck spaces shows the danger space, clivus, true retropharyngeal space, an alar portion of the deep layer of deep cervical fascia, visceral fascia, a prevertebral portion of the deep layer of deep cervical fascia, posterior pharyngeal wall, and prevertebral space.

Contributed by B Palmer

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Deep Cervical Fascia of the Neck. The deep cervical fascia of the neck, which is located at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra, is highlighted in blue.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Cunha L, Almeida M, Cordeiro I, Baptista A. Spontaneous Cervical Spondylodiscitis With Retropharyngeal Abscess and Bacteremia: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023 Jun:15(6):e40246. doi: 10.7759/cureus.40246. Epub 2023 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 37440813]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFaruqui S, Palacios E, Friedlander P, Melgar M, Alvernia J, Parry PV. Nontraumatic retropharyngeal abscess complicated by cervical osteomyelitis and epidural abscess in post-Katrina New Orleans: four cases. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2009 Jul:88(7):E14 [PubMed PMID: 19623518]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAngajala V, Hur K, Jacobson L, Hochstim C. Geographic health disparities in the Los Angeles pediatric neck abscess population. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2018 Oct:113():134-139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.07.043. Epub 2018 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 30173972]

Jain A, Singh I, Meher R, Raj A, Rajpurohit P, Prasad P. Deep neck space abscesses in children below 5 years of age and their complications. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2018 Jun:109():40-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.03.022. Epub 2018 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 29728182]

Quinn NA, Olson JA, Meier JD, Baskin H, Schunk JE, Thorell EA, Hodo LN. Pediatric lateral neck infections - Computed tomography vs ultrasound on initial evaluation. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2018 Jun:109():149-153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.04.001. Epub 2018 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 29728170]

Joshua J, Scholten E, Schaerer D, Mafee MF, Alexander TH, Crotty Alexander LE. Otolaryngology in Critical Care. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2018 Jun:15(6):643-654. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201708-695FR. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29565639]

Mettias B, Robertson S, Buchanan MA. Retropharyngeal abscess after chemotherapy. BMJ case reports. 2018 Mar 5:2018():. pii: bcr-2017-222610. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222610. Epub 2018 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 29507016]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGottlieb M, Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical Mimics: An Emergency Medicine-Focused Review of Streptococcal Pharyngitis Mimics. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2018 May:54(5):619-629. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.01.031. Epub 2018 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 29523424]

Pollard BA, El-Beheiry H. Pott's disease with unstable cervical spine, retropharyngeal cold abscess and progressive airway obstruction. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 1999 Aug:46(8):772-5 [PubMed PMID: 10451137]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAkhavan M. Ear, Nose, Throat: Beyond Pharyngitis: Retropharyngeal Abscess, Peritonsillar Abscess, Epiglottitis, Bacterial Tracheitis, and Postoperative Tonsillectomy. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2021 Aug:39(3):661-675. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2021.04.012. Epub 2021 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 34215408]

Derinkuyu BE, Boyunağa Ö, Polat M, Damar Ç, Tapısız Aktaş A, Alımlı AG, Öztunalı Ç, Kara SS, Uçar M, Tezer H. Association between deep neck space abscesses and internal carotid artery narrowing in pediatric patients. Turkish journal of medical sciences. 2017 Dec 19:47(6):1842-1847. doi: 10.3906/sag-1707-165. Epub 2017 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 29306247]

Argintaru N, Carr D. Retropharyngeal Abscess: A Subtle Presentation of a Deep Space Neck Infection. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Oct:53(4):568-569. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.06.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29079072]

LeRiger MM, Miler V, Tobias JD, Raman VT, Elmaraghy CA, Jatana KR. Potential for severe airway obstruction from pediatric retropharyngeal abscess. International medical case reports journal. 2017:10():381-384. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S146661. Epub 2017 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 29200894]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen XH, Lin GB, Lin C, She DJ, Lin X, Chen ZH, Chen JM, Zhang R. [The diagnosis and treatment strategy for patients with severemultispace abscesses in neck]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology, head, and neck surgery. 2016 Sep 5:30(17):1388-1393. doi: 10.13201/j.issn.1001-1781.2016.17.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29798464]

Cheng Z, Yu J, Xiao L, Lian Z, Wei Y, Wang J. [Deep neck infection: clinical analyses of 95 cases]. Zhonghua er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Chinese journal of otorhinolaryngology head and neck surgery. 2015 Sep:50(9):769-72 [PubMed PMID: 26696352]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoucher C, Dorion D, Fisch C. Retropharyngeal abscesses: a clinical and radiologic correlation. The Journal of otolaryngology. 1999 Jun:28(3):134-7 [PubMed PMID: 10410343]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceScott PM, Loftus WK, Kew J, Ahuja A, Yue V, van Hasselt CA. Diagnosis of peritonsillar infections: a prospective study of ultrasound, computerized tomography and clinical diagnosis. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 1999 Mar:113(3):229-32 [PubMed PMID: 10435129]

Glasier CM, Stark JE, Jacobs RF, Mancias P, Leithiser RE Jr, Seibert RW, Seibert JJ. CT and ultrasound imaging of retropharyngeal abscesses in children. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 1992 Jul-Aug:13(4):1191-5 [PubMed PMID: 1636535]

Adoviča A, Veidere L, Ronis M, Sumeraga G. Deep neck infections: review of 263 cases. Otolaryngologia polska = The Polish otolaryngology. 2017 Oct 30:71(5):37-42. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.5315. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29154249]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLorrot M, Haas H, Hentgen V, Van Den Abbeele T, Bonacorsi S, Doit C, Cohen R, Grimprel E. [Antibiotherapy of severe ENT infections in children: peripharyngeal abscesses]. Archives de pediatrie : organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie. 2013 Nov:20 Suppl 3():e1-4. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(13)71419-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24360295]

Behari S, Nayak SR, Bhargava V, Banerji D, Chhabra DK, Jain VK. Craniocervical tuberculosis: protocol of surgical management. Neurosurgery. 2003 Jan:52(1):72-80; discussion 80-1 [PubMed PMID: 12493103]

Kosko J, Casey J. Retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscesses: Factors in medical management failure. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2017 Jan:96(1):E12-E15 [PubMed PMID: 28122106]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWilkie MD, De S, Krishnan M. Defining the role of surgical drainage in paediatric deep neck space infections. Clinical otolaryngology : official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2019 May:44(3):366-371. doi: 10.1111/coa.13315. Epub 2019 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 30784193]

Maroun CA, Zalzal HG, Mustafa AA, Carr M. Transoral versus Transcervical Drainage of Pharyngeal Abscesses in Children: Post-Operative Complications. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2021 Sep:130(9):1052-1056. doi: 10.1177/0003489421990161. Epub 2021 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 33562999]

Dodson H, Cook J. Foreign Body Airway Obstruction. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31985979]

Regunath H, Oba Y. Community-Acquired Pneumonia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613500]

Kappus S, King O. Mediastinitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644692]

McDowell RH, Hyser MJ. Neck Abscess. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083634]

Gupta G, McDowell RH. Peritonsillar Abscess. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137805]

Sanders JL, Houck RC. Dental Abscess. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29630201]

Adhikari R, Soni A. Submandibular Sialadenitis and Sialadenosis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965882]

Wilson M, Pandey S. Parotitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809570]

Guerra AM, Waseem M. Epiglottitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613691]

Wolford RW, Goyal A, Belgam Syed SY, Schaefer TJ. Pharyngitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137834]

An J, Madeo J, Singhal M. Ludwig Angina. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29493976]

Allen BW, Anjum F, Bentley TP. Lemierre Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763021]

Ridder GJ, Technau-Ihling K, Sander A, Boedeker CC. Spectrum and management of deep neck space infections: an 8-year experience of 234 cases. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2005 Nov:133(5):709-14 [PubMed PMID: 16274797]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSanz Sánchez CI, Morales Angulo C. Retropharyngeal Abscess. Clinical Review of Twenty-five Years. Acta otorrinolaringologica espanola. 2021 Mar-Apr:72(2):71-79. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2020.01.005. Epub 2020 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 32487430]

Côrte FC, Firmino-Machado J, Moura CP, Spratley J, Santos M. Acute pediatric neck infections: Outcomes in a seven-year series. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2017 Aug:99():128-134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.05.020. Epub 2017 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 28688554]

Soldatsky YL, Denisova OA, Bulynko SA. [The specific features of the past medical history and etiology of pharyngeal abscess in the children]. Vestnik otorinolaringologii. 2017:82(5):12-14. doi: 10.17116/otorino201782512-14. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29072654]

Bochner RE, Gangar M, Belamarich PF. A Clinical Approach to Tonsillitis, Tonsillar Hypertrophy, and Peritonsillar and Retropharyngeal Abscesses. Pediatrics in review. 2017 Feb:38(2):81-92. doi: 10.1542/pir.2016-0072. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28148705]

Caccamese JF Jr, Coletti DP. Deep neck infections: clinical considerations in aggressive disease. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2008 Aug:20(3):367-80. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2008.03.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18603197]