Introduction

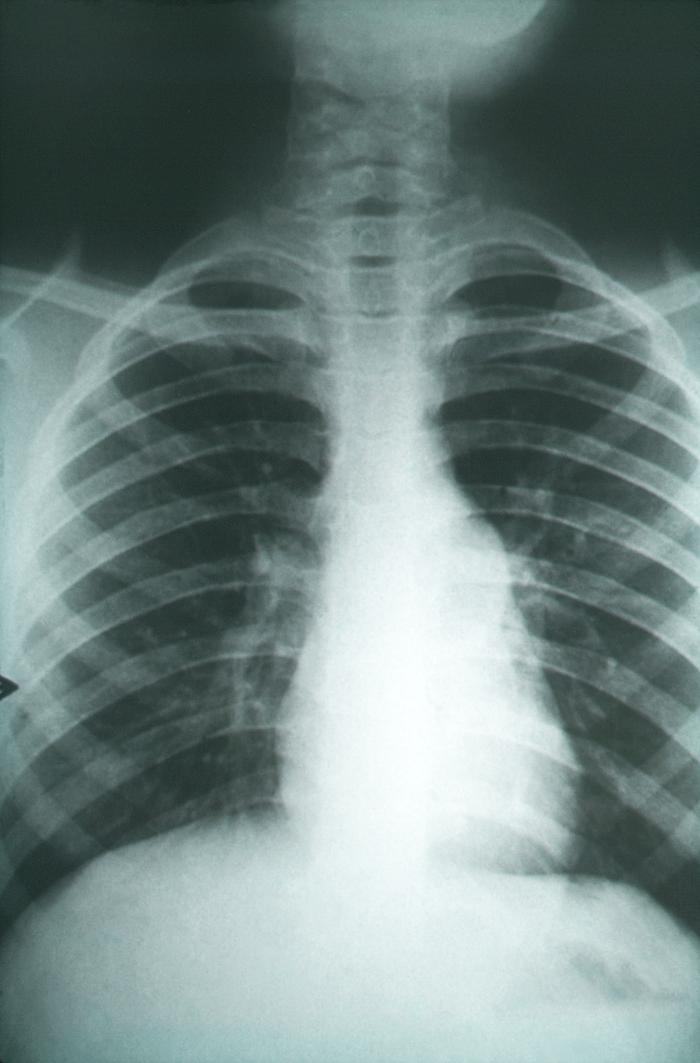

The dimorphic fungus Coccidioides causes coccidioidomycosis, also known as San Joaquin Valley fever, which is endemic to the arid regions of the Western Hemisphere. Coccidioides was first discovered by a medical intern in 1892 and was later named Coccidioides immitis. Coccidioidomycosis has a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, from asymptomatic infection to fatal disease.[1][2][3][4] See Image. Coccidioidomycosis.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Coccidioides is a genus of dimorphic fungi that exist as mycelia or as spherules (1). Both mycelia and spherules are asexual forms. The sexual form of coccidiosis has not been found. Molecular analysis suggests Coccidioides is related to ascomycetes such as Histoplasma capsulated or Blastomyces dermatitidis. Two species within the genus Coccidioides are recognized, namely, C. immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. C. immitis is found in California, while C. posadasii is found in other US states and other parts of the world. These 2 species' clinical manifestations and in vitro susceptibilities are the same. The 2 Coccidioides species are phenotypically identical and can only be identified by molecular methods. Therefore, Coccidioides species are not routinely identified at the species level in clinical microbiology laboratories. This fungus likes arid deserts with high salt content. In soil, and agar, the Coccidioides grow as mycelia or filamentous form.

Arthroconidia, the infectious particles of Coccidiosis species, are deposited in the lung when inhaled. Arthroconidia transform into spherules in the lung and tissues. Spherules are filled with endospores (2 micrometers to 5 micrometers). This spherule can burst in tissues releasing endospores, which can magnify the infection. Coccidioides species grow well on most mycologic or bacteriologic media after 5 or 7 days of incubation. Typically, the colonies are white. However, appearance is nondiagnostic. The yeast is very infectious at this stage. Outbreaks in the laboratory personnel have occurred; therefore, the laboratory must be informed when Coccidiosis species are suspected.[5][6][7]

Epidemiology

Coccidioides is endemic to California, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and New Mexico. Coccidioidomycosis is a reportable disease. For unknown reasons, the incidence rates in Arizona have increased lately. In 2011, coccidioidomycosis was 42.6 cases per 100,000 population and highest among persons aged 60 to 79 (69.1/100,000). In some areas within the endemic region, Valley fever can cause an estimated 15% to nearly 30% of community-acquired cases of pneumonia. C. immitis can cause disease in non-endemic regions due to wind carrying the infectious particles over long distances.

Pathophysiology

Coccidioides species exist as mycelia in the environment and the laboratory. Mycelia grow by apical extension, forming true septae along their course. In 1 week, these mycelial cells undergo a process of autolysis and thinning of their cell walls. Some of the remaining cells in the colony are transformed into barrel-shaped, loosely adherent arthroconidia. The arthroconidia are loosely connected, becoming airborne at the slightest perturbation. Arthroconidia are 2 microns to 5 microns in length and are the right size to reach the terminal bronchiole when inhaled. Once inside the lung, arthroconidia undergo remodeling from rectangular to spherical forms known as spherules. This transformation is facilitated by the shedding of the outer layer of the arthroconidia. The spherules grow to a size of 75 microns in diameter. The spherules divide internally by developing internal septae, which divide the spherule into compartments. Each compartment has endospores. As the spherule impregnated with endospores grows, it eventually ruptures and releases the endospores in the region, including the alveolar sacs. The alveolar macrophages pick up these endospores. The local release of endospores causes host response, and acute inflammation ensues. The endospores can further multiply within tissues and, when released in the environment, can lead to mycelial growth.

Occasionally, spherule may leave the lung to set up an extrapulmonary infection in susceptible patients. The most likely dissemination routes appear due to the trafficking of the macrophages carrying the spherules or the endospores. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy is frequently seen in coccidioidomycosis patients who have an extrapulmonary disease. Histopathology of the tissues infected with coccidioidomycosis shows cellular components of both acute and chronic inflammation. Neutrophils and eosinophils are attracted to the local region when spherules rupture and release endospores. Chronic granulomatous infection is associated with mature unruptured spherules, suggesting that the infection due to Ccoccidioides species has been controlled. The mainstay of the defense against Coccidioides species is the T-lymphocytes, particularly the T-helper2 lymphocytes (Th2). Th2 dysfunction or deficiency has been found in patients with an extrapulmonary or disseminated disease. The innate cellular immunity is useful in the early infection when the arthroconidia reach the terminal bronchioles, when spherules are small, or when the endospores are released. As the spherules grow larger, the effector cells of innate immunity, for example, neutrophils, monocytes, and natural killer cells, become ineffective.

History and Physical

The majority of infections are asymptomatic (60%), and when symptoms do occur, the presentation can be confused with community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. Symptoms appear 7 to 21 days post-exposure. Fever, cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain are most frequent. The clinical presentation may be acute or sub-acute based on the inoculum size. A headache, weight loss, and rash are often seen. The rash is faint, maculopapular, transient, occurs early during disease, and is often missed. Erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme occurs more frequently in women. Migratory arthralgias are also common. The triad of fever, erythema nodosum, and arthralgias (especially of the knees and ankles) has been termed desert rheumatism. Laboratory findings include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and eosinophilia. Chest x-ray (CXR) shows unilateral infiltrates. Hilar and peritracheal adenopathy suggest the extrathoracic spread of the disease. Lung cavities are present in only 8% of adults but are more frequent in children. Other pulmonary manifestations are nodules and cavities in the early phase and fibrocavitary disease in the chronic phase. Cavities are peripheral, often solitary, and develop a distinctive thin wall with time. If the cavity is diagnosed early, surgical resection of the cavity and closure of the pulmonary leak is the preferred treatment. The pleural disease may occur in one-third of patients.

Dissemination is frequent in the immunocompromised host, pregnant patients, and patients who have African and Filipino ancestry. Skin lesions are common. Often, there are no pulmonary infiltrates on CXR. Vertebral osteomyelitis is common, and the disease pattern mimics vertebral osteomyelitis due to Staphylococcus aureus, including findings such as psoas abscess and epidural abscess. Joint involvement is common, with knee joints being most frequently involved. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement occurs in 90% of these cases. If untreated, CNS disease is always fatal. Eosinophil predominance is found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Basilar meninges are often affected, and hydrocephalus is a common complication.

Evaluation

Isolating Coccidioides organisms in a patient is evidence of a coccidioidal infection, and this diagnostic approach is used most frequently in patients with complicated pulmonary or disseminated syndromes. Sputum collection has no risk of transmission.[8][9] Professionals most frequently use serologic testing to diagnose primary coccidial infections. Often, the patients may not have sputum production, and fungal cultures are not feasible. CSF cultures are often negative in coccidioidomycosis. Minimally reactive test results should not be dismissed as insignificant. A negative serologic test result does not exclude the presence of coccidial infection. Therefore, the test should be repeated over the course of 2 months.

Detection of tube precipitin antibodies is sometimes called the IgM test. The polysaccharide antigen of the fungal cell wall is responsible for this antibody. Tube precipitin antibodies are detected in 90% of patients in the first 3 weeks after exposure. The prevalence of tube precipitin antibodies decreases to 5% by 7 months after exposure. Complement-fixing antibodies are immunoglobulin G (IgG); the antigen responsible for these antibodies is chitinase. Complement-fixing antibodies can be detected in other body fluids, and their detection in cerebrospinal fluid is an especially important aid in diagnosing coccidial meningitis. Complement-fixing antibody concentration is expressed as a titer, such as 1:4 or 1:64.

An enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is available to detect Coccidiosis IgM and IgG antibodies. However, the results are not interchangeable with the immunodiffusion and complement-fixing tests because different antigens are used for EIA. Enzyme immunoassay results should be confirmed with immunodiffusion tube precipitin, immunodiffusion complement-fixing (IDCF), or complement-fixing test because these tests have established a track record. Nevertheless, positive results with the EIA commercial kit are highly sensitive (95%) for coccidiosis infection, but false-positive results occur more frequently compared to TP and complement-fixing antibodies tests. Antibodies detected by the original tube precipitin or complement-fixing tests can be detected by alternative procedures known as the immunodiffusion tube precipitin and immunodiffusion complement-fixing tests. Although these tests are conducted similarly, different antigens are used to measure different types of antibodies. Test results are as sensitive as the tube precipitin and complement-fixing antibody detection tests.

Overall, the serological tests are likely positive in a normal host exposed to Coccidioides species. In a study of 41 patients with culture-confirmed coccidioidomycosis, the complement-fixing antibodies were positive in 23 (56%), the IDCF in 29 (71%), and the EIA in 34 (81%). In 6 (15%) patients, all serologic tests were negative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) probes to detect coccidiosis DNA directly in the patient’s clinical specimens are unavailable commercially. Genomic studies in research settings show that PCR tests are 98% sensitive and 100% specific. A specific ribosomal RNA sequence can be detected using a commercially available DNA probe (Gen-Probe, San Diego) in mycelia grown in the laboratory. Currently, molecular methods to differentiate between C. immitis and C. posadasii are available only at limited reference laboratories. Latex tests are simple to use and are widely available in clinical settings, but they are less sensitive. There are significant numbers of false-positive reactions. Antigenemia and antigenuria may occur with early or chronic Coccidioides infections. The PCR test, if applied to CSF, is particularly useful for the diagnosis of meningitis because frequently the CSF cultures are negative. In a study of 24 immunosuppressed patients with coccidioidomycosis, most (17/24; 71%) had a positive urine antigen test. The Histoplasma antigenuria assay was positive in 14 patients, confirming the cross-reactivity between the 2 fungi.

Treatment / Management

In 2016, the Infectious Disease Society of America published treatment guidelines for coccidioidomycosis. Coccidioidomycosis has a wide clinical spectrum of presentation. Patients can have a mild respiratory illness with infiltrates or can have chronic pulmonary disease presenting as nodules, cavities, or fibrocavitary disease. In a small percentage of mostly immunocompromised patients, coccidioidomycosis can present as a disseminated disease. The preferred drug is Diflucan, with a dose of 400 mg to 1200 mg daily. Itraconazole is an alternative, but there are increased drug interactions with itraconazole.[10][11][12](A1)

Pulmonary Infections

Primary pulmonary infections, if severe, should be treated. Some of the reasons to treat a patient are as follows:

- weight loss of 10% or more

- intense night sweats, persisting symptoms longer than 3 weeks

- infiltrates involving more than one-half of 1 lung or bilateral lung involvement

- prominent hilar adenopathy

- CF antibody test titers equal to or greater than 1:16

- inability to work due to symptoms

- symptoms persist for 12 months

- patient age greater than 55 years.

Three months of treatment with oral azole should suffice. Asymptomatic pulmonary nodules due to coccidiosis infection should be followed by imaging. If the nodule is growing, and if there is a concern for malignancy, then resection of the nodule should be considered. Post-resection, there is no need to treat unless the patient is immunocompromised. Some experts would treat for 3 months as mop-up therapy if live yeasts were present in the pathology specimen (unpublished data). Asymptomatic cavities should be followed with serial imaging. If the cavity persists for over 2 years, is close to the pleura, or is enlarging, some experts recommend resection to avoid future complications, although good evidence is lacking. Cavitary coccidioidomycosis can be treated if there is local discomfort, superinfection with other fungi, or bacteria if there is hemoptysis or rupture of the cavity into the pleural space with resulting pyopneumothorax. Treatment durations are about 3 to 6 months. Treatment with azoles, such as fluconazole, is recommended for patients with fibrocavitary disease. If there is sufficient response, these patients should be treated for a year. Surgical management may be needed for severe localized disease, particularly if hemoptysis has occurred. In patients who have diffuse pneumonia, such as with bilateral diffuse reticulonodular or miliary infiltrates, Amphotericin B may be used. These patients have had exposure to a large inoculum, or there could be an underlying unrecognized immunocompromised state. Patients with diffuse pneumonia should also be evaluated for extrapulmonary coccidiosis infection.

Coccidioides Meningitis

Coccidioides meningitis does not respond to intravenous Amphotericin due to poor bioavailability across the blood-brain barrier. It can present in various ways, but headache is the most common symptom. Hydrocephalus is common and may be present early or late during the disease. It is a common complication. The most common life-threatening complication of coccidial meningitis in the modern era is CNS vasculitis, leading to cerebral ischemia, infarction, and hemorrhage. Clinically, a patient may present with cerebral infarction and stroke. Spinal arachnoiditis may occur as a complication, but unlike infarctions and hydrocephalus, arachnoiditis is not an initial presentation. Recently, there has been an increase in the incidence of spinal arachnoiditis post-treatment with azole antifungal agents. Spinal arachnoiditis responds better to intrathecal amphotericin B. Cerebral abscesses and mass lesions secondary to Coccidioides infection have rarely been reported. Eosinophils in CSF are uncommon but, when present, are suggestive of the diagnosis. More typical is the lymphocytic predominance, but neutrophil predominance is often seen. Fluconazole was demonstrated to be equivalent to amphotericin B in 1988 and since then has been the drug of choice at 800 mg to 1200 mg daily dose. Both clinical and CSF parameters should be monitored at least monthly. Once improvement occurs, follow-up may be done every 3 months for life. Therapy is lifelong in these patients.

HIV Patients

The infection rate has declined dramatically since the advent of antiretroviral therapy. Pulmonary disease is often diffused and can be confused with pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci. During the epidemic's peak, about half of the patients with coccidiosis infection were outside endemic areas. Therefore, coccidioidomycosis in HIV patients should be in the differential regardless of the location. The symptoms of meningitis in HIV patients are identical to those of non-HIV patients. A headache is frequently present. All HIV patients with clinically active coccidioidomycosis must be treated if CD4 counts are below 250. Patients on antiretroviral therapy whose CD4 counts are over 250 and stable can safely stop therapy. Patients who have meningitis should continue therapy indefinitely. All localized pulmonary infections should be treated in patients with HIV. While oral azole can be used for a mild infection, amphotericin B is preferable for moderate to severe infections. Combination therapy with azole and amphotericin B is recommended in severe infections.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for coccidioidomycosis include the following:

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Blastomycosis

- Enteropathic arthropathies

- Eosinophilic pneumonia

- Granuloma

- Histoplasmosis

- Lung abscess

- Lung cancer

- Lymphoma

- Myelophthisic anemia

Pearls and Other Issues

Transplant Patients

In addition to new infections in endemic areas, reactivations can occur in transplant patients when cell-mediated immunity decreases. Most reactivation disease occurs in the first 3 months after solid organ transplantation. Transmission by the donor organs results in rapid onset after surgery and results in a severe infection. Acute infections in transplant patients are likely to become disseminated. The most common sites are skin, bones, subcutaneous tissues, and meninges. Fungemia is more common in transplant recipients than in other immunocompromised patients. Diagnosis depends on the culture and identification of the fungus in tissues and body fluids. Serological tests are not helpful in this group of patients. Spherules can be identified in sputum, BAL, body fluids, and tissue biopsies. Spherules may be seen in hematoxylin and eosin stains but should be sought using silver methenamine staining.

Treatment with liposomal amphotericin B, 3 mg/kg to 5 mg/kg daily, should be initiated in all transplant recipients. If there is a durable response, the therapy can be switched to oral azole for at least 12 months or if the patient remains immunosuppressed. Chronic suppressive therapy may be used in high-risk patients, such as those with African or Filipino ancestry or those in endemic regions. In meningitis, fluconazole should be used in addition to amphotericin B. Fluconazole of 800 mg daily is recommended in cases of meningitis. Intrathecal amphotericin B may be considered if there is a failure of azole therapy. Several transplant centers in the endemic area routinely evaluate for coccidiosis infection before transplant. If the recipient had a history or evidence of infection in the past 1 to 2 years, fluconazole prophylaxis is routinely used in the first year of transplantation. If the organ donor turns out to be positive for antibodies, the recipient receives lifelong fluconazole prophylaxis (10). Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients with a history of coccidiosis infection should get azole prophylaxis until complete recovery of T-cell function.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team in the management of coccidioidomycosis. Most patients present to the primary care provider, nurse practitioner, or internist. Some patients may have an incident x-ray finding of the disease and no symptoms. In 2016, the Infectious Disease Society of America published treatment guidelines for coccidioidomycosis. Symptomatic patients need treatment, but asymptomatic patients can be observed. In addition, patients who are immunocompromised or have a transplant need treatment. The outlook for most patients is excellent, but immunocompromised patients may have a guarded prognosis.[13][14][15]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Deresinski S, Mirels LF. Coccidioidomycosis: What a long strange trip it's been. Medical mycology. 2019 Feb 1:57(Supplement_1):S3-S15. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy123. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30690606]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 30690604]

Hung CY, Hsu AP, Holland SM, Fierer J. A review of innate and adaptive immunity to coccidioidomycosis. Medical mycology. 2019 Feb 1:57(Supplement_1):S85-S92. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy146. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30690602]

Taylor JW,Barker BM, The endozoan, small-mammal reservoir hypothesis and the life cycle of Coccidioides species. Medical mycology. 2019 Feb 1; [PubMed PMID: 30690603]

Thompson GR 3rd, Lewis JS 2nd, Nix DE, Patterson TF. Current Concepts and Future Directions in the Pharmacology and Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. Medical mycology. 2019 Feb 1:57(Supplement_1):S76-S84. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy029. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30690601]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSondermeyer Cooksey GL, Jain S, Vugia DJ. Epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis among children in California, 2000-2016. Medical mycology. 2019 Feb 1:57(Supplement_1):S64-S66. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy066. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30690598]

Laniado-Laborín R, Arathoon EG, Canteros C, Muñiz-Salazar R, Rendon A. Coccidioidomycosis in Latin America. Medical mycology. 2019 Feb 1:57(Supplement_1):S46-S55. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy037. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30690597]

Lauer A, Baal JD, Mendes SD, Casimiro KN, Passaglia AK, Valenzuela AH, Guibert G. Valley Fever on the Rise-Searching for Microbial Antagonists to the Fungal Pathogen Coccidioides immitis. Microorganisms. 2019 Jan 24:7(2):. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7020031. Epub 2019 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 30682831]

Davis MR, Nguyen MH, Donnelley MA, Thompson Iii GR. Tolerability of long-term fluconazole therapy. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2019 Mar 1:74(3):768-771. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky501. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30535104]

Donovan FM, Zangeneh TT, Malo J, Galgiani JN. Top Questions in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. Open forum infectious diseases. 2017 Fall:4(4):ofx197. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx197. Epub 2017 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 29670928]

Kontoyiannis DP. What to Do for the Asymptomatic Pulmonary Coccidioidal Nodule or Cavity in Immunosuppressed Patients? A Focus in the Recent Coccidioidomycosis Guidelines. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017 Jan 15:64(2):232-233. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw733. Epub 2016 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 27986674]

Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, Catanzaro A, Geertsma F, Hoover SE, Johnson RH, Kusne S, Lisse J, MacDonald JD, Meyerson SL, Raksin PB, Siever J, Stevens DA, Sunenshine R, Theodore N. 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016 Sep 15:63(6):e112-46. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw360. Epub 2016 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 27470238]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSidhu R, Lash DB, Heidari A, Natarajan P, Johnson RH. Evaluation of Amphotericin B Lipid Formulations for Treatment of Severe Coccidioidomycosis. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2018 Jul:62(7):. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02293-17. Epub 2018 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 29686150]

Martinez-Del-Campo E, Kalb S, Rangel-Castilla L, Moon K, Moran A, Gonzalez O, Soriano-Baron H, Theodore N. Spinal Coccidioidomycosis: A Current Review of Diagnosis and Management. World neurosurgery. 2017 Dec:108():69-75. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.08.103. Epub 2017 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 28844921]

Chaudhary S, Meinke L, Ateeli H, Knox KS, Raz Y, Ampel NM. Coccidioidomycosis among persons undergoing lung transplantation in the coccidioidal endemic region. Transplant infectious disease : an official journal of the Transplantation Society. 2017 Aug:19(4):. doi: 10.1111/tid.12713. Epub 2017 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 28452423]