Introduction

Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) of the carotid artery is a non-atherosclerotic and noninflammatory disease that can lead to stenosis and/or aneurysm of medium-sized arteries. FMD is a rare disease that mainly affects the distal extracranial internal carotid and renal arteries. FMD most commonly affects middle-aged women; however, it can affect anyone of any age and gender.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The origins of fibromuscular dysplasia are unknown; however, there are several theories of etiology. One theory shows FMD to be an inherited disorder as it appears there is an 11% familial prevalence. Hormonal effects are another possible etiology as the disease shows predominance in women. Hormones have a particular effect on the medial tissue of the arterial wall. Other theories include immunologic injury, abnormal embryologic development, and abnormal distribution of vaso vasorum.[2][4][3]

Epidemiology

The incidence of fibromuscular dysplasia in the general population is approximately 0.42% to 3.4%. Risk factors include gender, age, and history of smoking. The disease primarily affects middle-aged women in the fifth decade of life. In most studies, up to 90% of patients with FMD have been women. The carotid artery is involved in 75% of cases and is often bilateral, with about two-thirds having an additional arterial bed involved. FMD commonly correlates with cerebral aneurysms (31%), fibromuscular dysplasia of the renal arteries (up to 40%), and dissections (63.7%). Gender differences have been identified as well. Fibromuscular dysplasia affects women twice as often as men. Women are more likely to have extracranial internal carotid artery involvement and are at higher risk for cervical (carotid and vertebral) dissections and aneurysms. Men have a higher incidence of renal artery involvement and are more likely to have renal dissections.[2][5][4]

Pathophysiology

There are four types of FMD. The most common type in the carotid arteries is medial fibroplasia, present in 85% of cases. The usual location is opposite the C1 through C3 vertebral bodies and disks. Medial fibroplasia characteristically shows compact fibrous connective tissue replacing the smooth muscle of the media. The media may also show accumulation of collagen and ground substance separating disorganized smooth muscle cells. The other three types are perimedial dysplasia (approximately 10%), intimal fibroplasia (approximately 5%), and medial hyperplasia which are rare. The disease preferentially affects long arteries with few branches.[1]

History and Physical

Patients may either be symptomatic or asymptomatic and can vary depending on the involvement of the arterial segment. Most common symptoms are similar to atherosclerotic disease including transient ischemic attack, stroke, and hypertension. Nonspecific symptoms include dizziness, headaches, tinnitus, chest pain and shortness of breath. On physical exam, Horner syndrome (generally limited to ptosis and miosis) can be noted, most likely due from pressure on the sympathetic fibers from the carotid artery. Reports of bruits in the carotids, epigastrium, and flanks also exist. Cranial nerve abnormalities and other neurologic deficits, as well as carotid bruit, have also been described.[5][4]

Evaluation

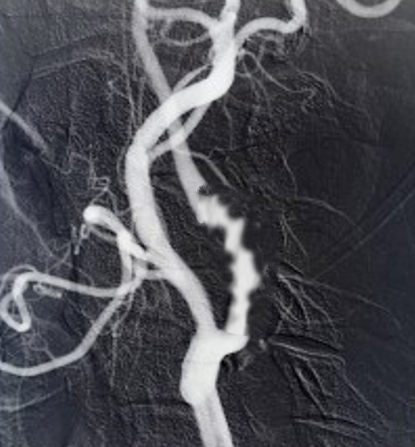

FMD is diagnosable by ultrasound, conventional arteriography, CT angiography, or MRA. The ultrasound can detect elevated velocities in the artery; however, it can remain undetected as FMD is generally more distal than the plaque. Arteriography is the gold standard for defining the features of FMD, and many cases are incidental findings from arteriography. The most common findings are focal stenosis which appears smooth and band-like and multifocal, giving the “string of pearls” appearance on imaging. The “pearls” (or beads) will be larger in diameter than the normal vessel.[6]

Treatment / Management

Treatment for asymptomatic patients includes smoking cessation, antiplatelet therapy, anti-hypertensives, and continual monitoring. Steroids and anticoagulation therapy have shown no role in treatment. Activities that would produce whiplash-like injuries should be avoided. Surgical treatment should be reserved for symptomatic patients or patients who have had no response to hypertension medications.

Surgical options include open surgical dilatation, open access balloon dilatation, or percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. The open surgical dilatation approach involves the use of rigid dilators progressively increasing in size and passed through the carotid artery. Access is similar to carotid endarterectomy; however, more exposure is needed to ensure dilation can be visualized and the extracranial carotid artery can be straightened during the passage of the dilator. This procedure, however, is done without imaging of the luminal surface; therefore, treatment is based on feel as the length of the segment and kinks must be estimated. Open access balloon dilatation is the choice when the disease process extends too far distally for dissection, and there is inadequate manual control of the dilation. This approach also allows for interval arteriography and avoidance of embolization. The last and preferred choice for proximal internal carotid involvement is percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA), which is an endovascular procedure which is best for lesions that demonstrate less kinking and no evidence of aneurysm. It also has fewer complications than open surgery. With this technique, a guide wire is inserted through the catheter which is then advanced. Further advancement of the guide wire then allows for the carotid sheath to be passed over the wire. Once the sheath is in place, it gets inflated.[7][8]

Differential Diagnosis

FMD should be differentiated from other cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and vasculitic processes. Atherosclerosis can also affect carotid and renal arteries, however, patients are generally older and have more risk factors such as diabetes and hyperlipidemia. Additionally, atherosclerosis can be seen in the proximal segments of arteries and do not exhibit the “string of pearls” appearance on imaging. FMD can involve multiple systems (renal and cerebral) and therefore should also be distinguished from vasculitis. Unlike vasculitis, however, there is generally no association with anemia, thrombocytopenia or other inflammatory processes. Inflammatory markers such as ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and CRP (C-reactive protein) would be negative in FMD.[1]

Complications

FMD can lead to many complications; however, they only occur in approximately 10% of cases. One such complication is carotid artery dissection leading to ruptures. Others include involvement of the arterial lumen causing a decrease in perfusion and the formation of thrombi which could lead to distal embolization. There are also concurrent issues that can arise and complicate management. These include atherosclerotic occlusion of the carotid bifurcation which makes it difficult to ascertain the cause of cerebral symptoms, extracranial carotid aneurysms, FMD of the vertebral and renal arteries.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

FMD is best managed by an interprofessional team that consists of a cardiologist, vascular surgeon, interventional radiologist, and an internist. The follow up of these patients is usually done by the primary care provider and nurse practitioner. Because of the diverse presentation, the treatment of FMD varies from angioplasty with stenting to open repair. Because the disease has no cure and is progressive, life long follows up is recommended. Often patients require multiple procedures to dilate the blood vessels, but eventually, some patients do develop end-stage renal disease, stroke, and manifestations of peripheral vascular disease.[9](Level V)

Media

References

Olin JW, Sealove BA. Diagnosis, management, and future developments of fibromuscular dysplasia. Journal of vascular surgery. 2011 Mar:53(3):826-36.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.10.066. Epub 2011 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 21236620]

Kadian-Dodov D, Gornik HL, Gu X, Froehlich J, Bacharach JM, Chi YW, Gray BH, Jaff MR, Kim ES, Mace P, Sharma A, Kline-Rogers E, White C, Olin JW. Dissection and Aneurysm in Patients With Fibromuscular Dysplasia: Findings From the U.S. Registry for FMD. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016 Jul 12:68(2):176-85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.044. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27386771]

Olin JW, Froehlich J, Gu X, Bacharach JM, Eagle K, Gray BH, Jaff MR, Kim ES, Mace P, Matsumoto AH, McBane RD, Kline-Rogers E, White CJ, Gornik HL. The United States Registry for Fibromuscular Dysplasia: results in the first 447 patients. Circulation. 2012 Jun 26:125(25):3182-90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.091223. Epub 2012 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 22615343]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKim ESH, Olin JW, Froehlich JB, Gu X, Bacharach JM, Gray BH, Jaff MR, Katzen BT, Kline-Rogers E, Mace PD, Matsumoto AH, McBane RD, White CJ, Gornik HL. Clinical manifestations of fibromuscular dysplasia vary by patient sex: a report of the United States registry for fibromuscular dysplasia. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013 Nov 19:62(21):2026-2028. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.038. Epub 2013 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 23954333]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcInnis CP, Haynor DR, Francis CE. Horner syndrome in fibromuscular dysplasia without carotid dissection. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2016 Apr:51(2):e53-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2015.10.019. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27085276]

Mettinger KL, Ericson K. Fibromuscular dysplasia and the brain. I. Observations on angiographic, clinical and genetic characteristics. Stroke. 1982 Jan-Feb:13(1):46-52 [PubMed PMID: 7064180]

Sharma AM,Kline B, The United States registry for fibromuscular dysplasia: new findings and breaking myths. Techniques in vascular and interventional radiology. 2014 Dec [PubMed PMID: 25770640]

Müller BT, Luther B, Hort W, Neumann-Haefelin T, Aulich A, Sandmann W. Surgical treatment of 50 carotid dissections: indications and results. Journal of vascular surgery. 2000 May:31(5):980-8 [PubMed PMID: 10805889]

Harriott AM, Zimmerman E, Singhal AB, Jaff MR, Lindsay ME, Rordorf GA. Cerebrovascular fibromuscular dysplasia: The MGH cohort and literature review. Neurology. Clinical practice. 2017 Jun:7(3):225-236. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000339. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28680766]