Introduction

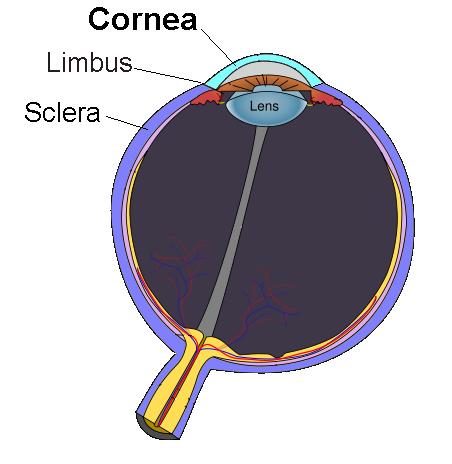

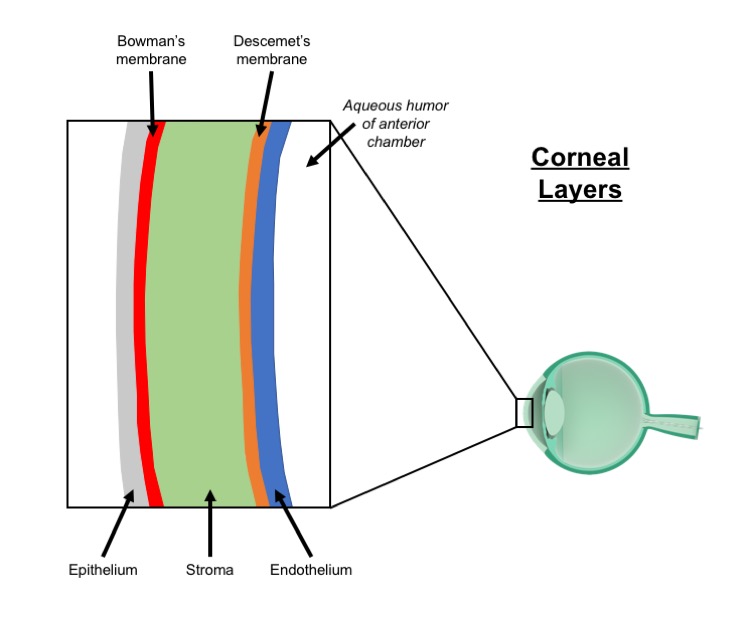

The cornea is the outermost, clear layer of the eye, immediately anterior to the anterior chamber, iris, and pupil. The cornea borders the sclera at the corneal limbus and is involved in the refraction of light entering the human eye. Five distinct layers make up the cornea, including the epithelium, Bowman's membrane, the stroma, Descemet's membrane, and the endothelium (from the exterior to interior). Albumin is the most abundant soluble protein in the human cornea.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

In addition to protecting the eye from outside infiltrates and ultraviolet radiation, the cornea is responsible for approximately 65% to 75% of the refraction of light as it passes through the eye. The cornea performs the initial refraction onto the lens, which further focuses the light onto the retina. Tears spread across the surface of the eye laterally in the blinking process. With their lipid, aqueous, and mucin components, tears are important to the maintenance of corneal health as they keep the cornea moist and clean.

The epithelium includes epithelial cells and a basement membrane. The primary functions of the corneal epithelium are twofold: to prevent the entrance of foreign objects or substances, and to accommodate the absorption of nutrients such as oxygen from the tears that pass over its surface.

Bowman's membrane is comprised of a thin, transparent layer of collagen. Trauma or injury can disrupt this collagenous film, which may cause scarring that impairs vision, depending on its location and extent.

The stroma is the thickest layer of the cornea. The stroma is made up primarily of water and collagen and is vital to the maintenance of the spherical shape of the cornea, which is critical to the proper passage and refraction of light into the eye.

Descemet's membrane is another thin layer that has relative strength due to the collagen fibers which comprise it. The corneal endothelial cells produce this collagen. Descemet's membrane is capable of repairing itself with relative ease following injury. It is crucial to protecting the internal structures of the eye from infection and trauma.

The innermost layer of the cornea is the endothelium. This thin layer plays a vital role in maintaining the clarity of the cornea as the endothelial cells pump excess fluid from the stroma. Endothelial cells do not appear to regenerate appreciably, and their destruction can cause lasting dysfunction.[1][2]][3]

Embryology

Corneal development begins with the formation of the presumptive corneal epithelium from the cranial ectoderm adjacent to the lens placode. Neural crest cell migration to the area between the presumptive epithelium and the lens later forms keratocytes or the stromal fibroblasts and the corneal endothelium.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Due to the importance of its transparency, the cornea does not contain any blood vessels. It receives nutrients through diffusion on its external side from tear fluid and the aqueous humor internally. The nerve fibers innervating the cornea also supply it with neurotrophins.[1]

Nerves

The corneal epithelium contains thousands of nerve endings that lend it high sensitivity to contact with foreign objects. Long ciliary nerves from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (V1) carry sensory innervation of the cornea. The density of nociceptors in the cornea is estimated at 300 to 600 times that of skin. The ciliary nerves form mid-stromal, subepithelial/sub-basal, and epithelial networks.[4][5]

Surgical Considerations

Corneal transplants divide into two main types: penetrating (full-thickness) keratoplasty and partial thickness corneal transplants. The type of corneal transplant performed is primarily determined by the condition of the cornea in the receiving eye. In Descemet's-stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK), Descemet's membrane and the endothelium are replaced with a corneal graft including some stroma while the superficial layers of the recipient cornea are left intact. Some physicians roughen the peripheral stroma with a scraping device to aid adherence of the graft. Descemet's membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) is the least aggressive type of corneal transplant as only Descemet's membrane, and the endothelium is replaced with donor tissue that does not include a stromal component.

Phototherapeutic keratectomy uses an excimer laser to remove the diseased part of the superficial cornea. This procedure may involve scar removal, smoothing of the cornea, epithelial erosion treatment, and the changing of corneal shape.[6][7][8][9]

Clinical Significance

Some of the most common conditions affecting the cornea include allergies, keratitis, dry eye, and injury. The majority of allergies affecting the eye are related to pollen, dust, or pet dander exposure, and symptoms may include itchiness, redness, stinging or burning, tearing, and excess watery discharge. These symptoms are often relieved by the administration of eye drops containing an antihistamine such as azelastine hydrochloride, emedastine difumarate, or levocabastine or mast-cell stabilizer drops such as ketotifen fumarate, cromolyn, lodoxamide, nedocromil, or pemirolast potassium. Multi-action eyedrops are also available. Inflammation of the cornea is referred to as keratitis, and often results from a minor injury, improper use of contact lenses, and infection. Antibacterial or antifungal drops may be used to treat the etiologic agent or prevent worsening of symptoms, and steroid eye drops may be of benefit in reducing the inflammation. Dry eye results from a lack of quality tear production often described as a "scratchy" feeling as if there is a foreign object in the eye. Injuries to the cornea vary widely in severity; minor scratches typically resolve spontaneously, whereas deep corneal abrasions can result in scarring, which may cause blurry vision, sensitivity to light, or pain.

Less commonly, corneal dystrophies may compromise corneal health. Corneal dystrophies involve opacification or modified shaping of one or more corneal layers. They affect both eyes, have a genetic component, and progress gradually. Keratoconus is a relatively common dystrophy estimated to affect approximately 1 in every 2000 people. Keratoconus involves a thinning and cone-shaped bulging of the cornea, which disrupts the normal transmission and refraction of light. Keratoconus is most commonly diagnosed in teenagers and young adults. Corrective measures include the use of corrective lenses, and in some cases, the implantation of intra-corneal inserts called Intacs; in severe cases, corneal transplantation could be necessary to preserve vision.

Corneal cross-linking involves the administration of riboflavin to the surface of the eye, followed by treatment with ultraviolet light to eliminate ectasia of the cornea. The FDA first approved the use of corneal cross-linking systems in the treatment of keratoconus in April 2016. Lattice corneal dystrophy involves amyloid deposition in the corneal stroma and follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. It divides into two primary types: in type 1, amyloid deposition is limited to the cornea, while type 2 exhibits systemic amyloid effects. As the condition progresses, patients experience recurrent corneal erosions and corneal opacification. Treatments aim to address these primary symptoms and may include the use of hypertonic saline eye drops, bandage contact lenses, artificial tears, laser surface ablation, and corneal transplantation. Fuchs dystrophy is a malady in which the corneal endothelial cells die. This condition impairs their ability to pump fluid out of the stroma, which results in fluid buildup in the cornea and consequent visual impairment. In the first stage of the disease, vision is hazy in the morning but improves as the day progresses, while in stage 2, vision becomes impaired throughout the day. Treatment typically aims to reduce the corneal swelling, which could involve the use of hypertonic saline eye drops or a hairdryer to dry the cornea. Severe cases may require corneal transplantation. Map-dot-fingerprint dystrophy or Cogan's dystrophy results from the abnormal development of the basement membrane of the corneal epithelium. It most commonly presents in patients between the ages of 40 and 70. Patients exhibit grayish outlines in the cornea on slit-lamp examination. The instability of the basement membrane can cause chronic epithelial erosions, which may lead to blurred vision and/or painful episodes due to the exposure of nerve endings lining the epithelium. Most cases receive treatment with lubricating eyedrops; in some patients, anterior corneal stromal punctures, corneal scraping, and phototherapeutic keratectomy may be options.

Iridocorneal endothelial syndrome (ICE) causes glaucoma, visible changes in the iris, and swelling of the cornea due to the movement of corneal epithelial cells to the iris. In ICE, treatment of the glaucoma is often requisite, and in cases of severe corneal compromise, transplantation may be necessary. Pterygia are triangular, pinkish growths on the cornea that are more prevalent in sunny climates. Surgical removal is only a recommendation in cases where vision is impaired, and the recurrence rate is approximately 50%.

Infectious agents that affect the cornea with relative frequency include varicella-zoster (shingles) virus and herpes simplex viruses. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is a varicella-zoster reactivation (shingles) involving the V1 dermatome. Anti-viral treatments may be of benefit for herpes zoster ophthalmicus since herpes virus infections can cause corneal damage, impairing vision.[10][11][12][13][14][15]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Laibson PR. Cornea and sclera. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1972 Nov:88(5):553-74 [PubMed PMID: 4343997]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRandleman JB, Khandelwal SS, Hafezi F. Corneal cross-linking. Survey of ophthalmology. 2015 Nov-Dec:60(6):509-23. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2015.04.002. Epub 2015 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 25980780]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRicard-Blum S, Ville G. Collagen cross-linking. The International journal of biochemistry. 1989:21(11):1185-9 [PubMed PMID: 2575544]

Physiology of the cornea., Mishima S,Hedbys BO,, International ophthalmology clinics, 1968 Fall [PubMed PMID: 4243831]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBelmonte C, Nichols JJ, Cox SM, Brock JA, Begley CG, Bereiter DA, Dartt DA, Galor A, Hamrah P, Ivanusic JJ, Jacobs DS, McNamara NA, Rosenblatt MI, Stapleton F, Wolffsohn JS. TFOS DEWS II pain and sensation report. The ocular surface. 2017 Jul:15(3):404-437. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.002. Epub 2017 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 28736339]

Panda A, Vanathi M, Kumar A, Dash Y, Priya S. Corneal graft rejection. Survey of ophthalmology. 2007 Jul-Aug:52(4):375-96 [PubMed PMID: 17574064]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSingh A, Zarei-Ghanavati M, Avadhanam V, Liu C. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcomes of Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty Versus Descemet Stripping Endothelial Keratoplasty/Descemet Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty. Cornea. 2017 Nov:36(11):1437-1443. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001320. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28834814]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWan Q, Wang D, Ye H, Tang J, Han Y. A review and meta-analysis of corneal cross-linking for post-laser vision correction ectasia. Journal of current ophthalmology. 2017 Sep:29(3):145-153. doi: 10.1016/j.joco.2017.02.008. Epub 2017 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 28913504]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSeitz B, Langenbucher A, Hager T, Janunts E, El-Husseiny M, Szentmáry N. Penetrating Keratoplasty for Keratoconus - Excimer Versus Femtosecond Laser Trephination. The open ophthalmology journal. 2017:11():225-240. doi: 10.2174/1874364101711010225. Epub 2017 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 28932339]

Wilson SE, Bourne WM. Corneal preservation. Survey of ophthalmology. 1989 Jan-Feb:33(4):237-59 [PubMed PMID: 2652359]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFong KS, Lin RV, Chee SP. Infections of the eye. Singapore medical journal. 1996 Feb:37(1):91-5 [PubMed PMID: 8783922]

Roberts C. Corneal topography: a review of terms and concepts. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 1996 Jun:22(5):624-9 [PubMed PMID: 8784639]

Gilbard JP. Dry eye: pharmacological approaches, effects, and progress. The CLAO journal : official publication of the Contact Lens Association of Ophthalmologists, Inc. 1996 Apr:22(2):141-5 [PubMed PMID: 8728623]

Hoppenreijs VP, Pels E, Vrensen GF, Treffers WF. Corneal endothelium and growth factors. Survey of ophthalmology. 1996 Sep-Oct:41(2):155-64 [PubMed PMID: 8890441]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoomaw MD, Cornea P, Rathbun RC, Wendel KA. Review of antiviral therapy for herpes labialis, genital herpes and herpes zoster. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2003 Aug:1(2):283-95 [PubMed PMID: 15482124]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence