Introduction

The vertebral column supports our body’s physical structure and nervous system, enabling movement and sensation. Pathology of the spine can lead to debilitating outcomes on quality of life. The vertebral column (spine) defines the animal subphylum Vertebra, or vertebrates, of the phylum Chordata. In humans, it is composed of 33 individual vertebrae grouped into the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal regions. There are 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 4 coccygeal vertebrae. Along with the skull, ribs, and sternum, these vertebrae make up the axial skeletal system.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The function of the spinal cord and spinal nerves includes:

- Protection of the spinal cord and spinal nerves

- The spinal cord is contained within the spinal canal, a central lumen within each vertebral body. Spinal nerves emerge from the main cord at each vertebral level to make up the sympathetic trunk and splanchnic nerves. The diameter of the spinal canal changes in the different parts of the vertebral column, larger in the cervical and lumbar regions and smaller in the thoracic region.

- Structural Support

- The spinal column forms the central axis of weight bearing and supports the head as well as transfers the weight of trunk and abdomen to the legs

- Provide structure as well as flexibility to the body

- Movement: The unique jointed structure of the spine allows rotation and bending

- In the thoracic region, the spine provides attachment sites for ribs.

- The spine serves as the attachment site for multiple muscles.

- Intervertebral discs: Provide cushioning between the vertebrae

- Cartilaginous structures between adjacent vertebrae composed of annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus

- The discs compose about 25% of the length of the vertebral column

- Support the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments

Embryology

The human skeleton begins to develop soon after conception. The notochordal process starts to form around day 17. The floor of the notochordal processes forms the notochordal plate after fusion of the roof of the yolk sac (of the underlying endoderm). The notochordal plate then folds inward to create the notochord. The notochord helps maintain the structure of the embryo and is the location of the development of the vertebral column. Parts of the notochord persist in adults to form the nucleus pulposus. Furthermore, the notochord stimulates the overlying ectoderm to form neuroectoderm, creating the neural plate. The neural plate gives rise to the neural tube, the rostral part becomes the adult brain, and the caudal end becomes the spinal cord.[1]

When the embryo begins gastrulation around 3 weeks, the sclerotome of somites, specifically the mesodermal portion, grows around the neural tube and notochord to form vertebral bodies and arches as well as the ribs. Each vertebral body is formed in a process called resegmentation from the fusion of 2 adjacent sclerotomes (caudal and cranial halves).

The vertebrae develop through endochondral ossification. Cartilage is formed first around week 6, and it is replaced with bone starting around week 7 to 8. Complete endochondral ossification occurs around age 26. Bony remodeling (degeneration and regeneration) occur throughout the lifespan.

Congenital Anomalies of the Spine

VACTERL (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, trachea-esophageal fistula, renal anomalies, limb anomalies): Defects of the spine in this association include fused vertebrae, missing or extra vertebrae, or misshapen vertebrae. While only 3 of these features are required for the diagnosis of this condition, 60% to 80% of patients with VACTERL have vertebral defects.[2]

Spina Bifida: incomplete closure of the vertebral column and meninges known as a neural tube defect. There are 3 types, and in order of increasing severity, they are spina bifida occulta, meningocele, and myelomeningocele. Myelomeningocele is often associated with Arnold-Chiari malformation and tethered spinal cord.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Spinal arteries originate from branches of larger arteries that supply the internal organs. The subclavian arteries of the neck branch into the vertebral arteries and ascending cervical arteries of the spine. The posterior intercostal arteries of the spine branch from the thoracic aorta while the lumbar arteries of the spine originate from the abdominal aorta. The lateral sacral arteries branch from the internal iliac arteries in the pelvis. Each of these arteries supplying the spine divides into an anterior and a posterior branch. The anterior branch supplies the vertebral body, and the posterior branch supplies the vertebral arch. Radicular arteries course along the middle, supplying the interior of the vertebral canal and vertebral column.

Radicular veins drain the smaller veins of the spinal cord and the internal and external vertebral veins. They empty into segmental and intervertebral veins. Blood flows from these vessels into 1 of 3 large vessels depending on the location. The superior vena cava drains the area of the cervical spine. The azygos and hemiazygos veins drain the thoracic area, and the inferior vena cava drains the lower regions of the lumbar and sacral spine.

Nerves

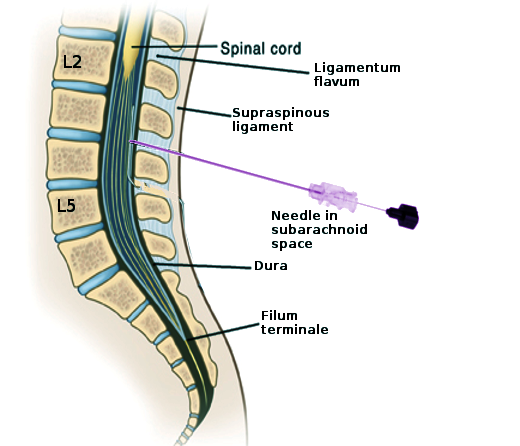

The central nervous system (CNS) is composed of the brain and spinal cord, while the peripheral nervous system consists of spinal nerves, cranial nerves, and their ganglia. The spinal cord is contained within the vertebral column. It extends from the base of the brain to the base of the spine where it comes to an end at the conus medullaris and filum terminale. The conus medullaris is the tapering, cone-shaped end of the spinal cord. It usually terminates at L1-L2 in adults but may extend further as an anatomical variant. In newborns, the conus medullaris is as low as L3-L4. The ending location is relevant for procedures such as the lumbar puncture to reduce the risk of cord trauma. The filum terminale is a delicate extension of the spinal cord from the conus medullaris that anchors to the dorsum of the coccyx. The cauda equina (“horse’s tail”) extend from the conus medullaris below.

Thirty-one pairs of spinal nerves exit the spinal cord and pass through the intervertebral foramen to innervate the periphery. Meningeal branches of spinal nerves innervate the vertebrae.

Muscles

As the central weight-bearing bony structure, the spine undergoes tremendous force. The muscles that attach to the spine help maintain posture and distribute the uneven force of the body’s weight. They are divided into the extrinsic and intrinsic back muscle groups.

The extrinsic muscles are further divided into superficial (trapezius, latissimus dorsi, levator scapulae, and the major and minor rhomboids) and intermediate (serratus posterior superior and serratus posterior inferior) groups. The superficial extrinsic muscles are involved in the movement of the upper limbs including movements of the scapula and humerus. The intermediate extrinsic muscles are involved in rib movement to aid respiration.

The intrinsic back muscles are separated into 3 layers: superficial, intermediate, and deep. These muscles aid in the movement of the spine and maintain postures. The superficial layer is made of the splenius capitis and splenius cervicis. These are involved in neck flexion, rotation, and extension. The intermediate layer is mostly made of the paraspinal or erector spinae muscles, the iliocostalis, longissimus, and spinalis. As the name implies, the erector spinae are important in extending and maintaining the central curvature of the spine.

The deep layer of the intrinsic back muscles includes muscles that lie between the transverse and spinous processes of the vertebrae. They are sometimes called the paravertebral muscles and include three groups of muscles. The semispinalis is the most superficial; it is prominent in the thoracic and cervical region. The multifidus is deep to semispinalis and most prominent in the lumbar region. Finally, the rotatores muscles are deepest and most prominent in the thoracic region.

The suboccipital muscles are located deep in the back of the neck. They attach to the skull and are involved in the movement of the head. These include the muscles that make up the suboccipital triangle: the rectus capitis posterior major, obliquus capitis superior, and obliquus capitis inferior. The importance of this triangle is that this is the location of the vertebral artery’s loop from the transverse foramen of the atlas to enter the foramen magnum of the skull where it supplies the brainstem.

Surgical Considerations

Surgery may be done for fractures, dislocations, tumors, scoliosis, or other mechanical defects. Care must be taken regarding a patient’s age, weight, and medical comorbidities. Complications may include neurological damage, incomplete relief of pain, vertebral fracture, and infection. [3]

Clinical Significance

Osteoarthritis: The progressive erosion of joint cartilage. This is the most common form of arthritis and often affects the spine. Advanced osteoarthritis may lead to hyperextension of the cervical spine and compression of spinal nerves causing pain.

Osteoporosis: Demineralization of the bones. Current USPSTF guidelines recommend screening for osteoporosis in all women aged 65 and older as well younger women with increased risk factors (assess using the FRAX tool). Severe osteoporosis increases the risk of developing a vertebral compression fracture.[4]

Seronegative spondyloarthropathies: Disease of the vertebral column that is typically associated with lack of the serum markers ANA and rheumatoid arthritis and has an increased incidence of HLA-B27. Conditions include ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and spondylitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

Spinal cord injury: Trauma to the vertebral column may lead to spinal cord damage with serious consequences such as paraplegia.

Spinal disc herniation: The intervertebral discs act as shock absorbers for load bearing and relaxing. Over time, or with injury, the discs may tear at the periphery along the annulus fibrosus leading to herniation of the internal nucleus pulposus. This can cause symptoms of pain, numbness, weakness, and decreased reflexes.

Spinal stenosis: Narrowing of the central spinal canal that can cause symptoms of numbness, weakness, or pain in the upper or lower extremities. This condition may be secondary to osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Paget disease of the bone, or trauma. Symptoms classically improve with bending forwards.

Spondylolisthesis: Complete dislocation with anterior displacement of one vertebra on another. This may increase pressure on spinal nerves, leading to pain in the nerve’s distribution.

Tuberculous spondylitis: Also known as Pott Disease, this is osteomyelitis of the vertebral bodies along with intervertebral discitis caused by advanced tuberculosis. Symptoms may include weakness of the lower limbs, kyphosis, back pain, fever, and weight loss.

Other Issues

The adult spine is normally curved slightly with cervical lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, and lumbar lordosis. This curvature originates during embryogenesis and further develops during childhood. Thoracic kyphosis and sacral curvature are formed during fetal development: the “fetal position.” Cervical curvature develops when babies begin to support the weight of their heads. Lumbar lordosis develops when children begin to stand and support their body weight. This curvature may become exaggerated or abnormal due to various pathological processes.

- Kyphosis: Humpback/hunchback. Increased anterior curvature (flexion) of the thoracic spine. Secondary to osteoporosis and poor posture and often seen in elderly.

- Lordosis: Swayback. Increased lumbar posterior curvature (extension). Secondary to anterior trunk muscle weakness which is more common in late pregnancy and obesity.

- Scoliosis: Abnormal lateral deviation and curvature of the spine. Secondary to the absence of part of a vertebra or vertebral muscle weakness and may include abnormal rotation of one vertebra. Results in neural compression and disc herniation. The classic patient is a teenage girl; may be genetic, secondary to trauma, or idiopathic.

- Kyphoscoliosis is a mixture of kyphosis and scoliosis.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

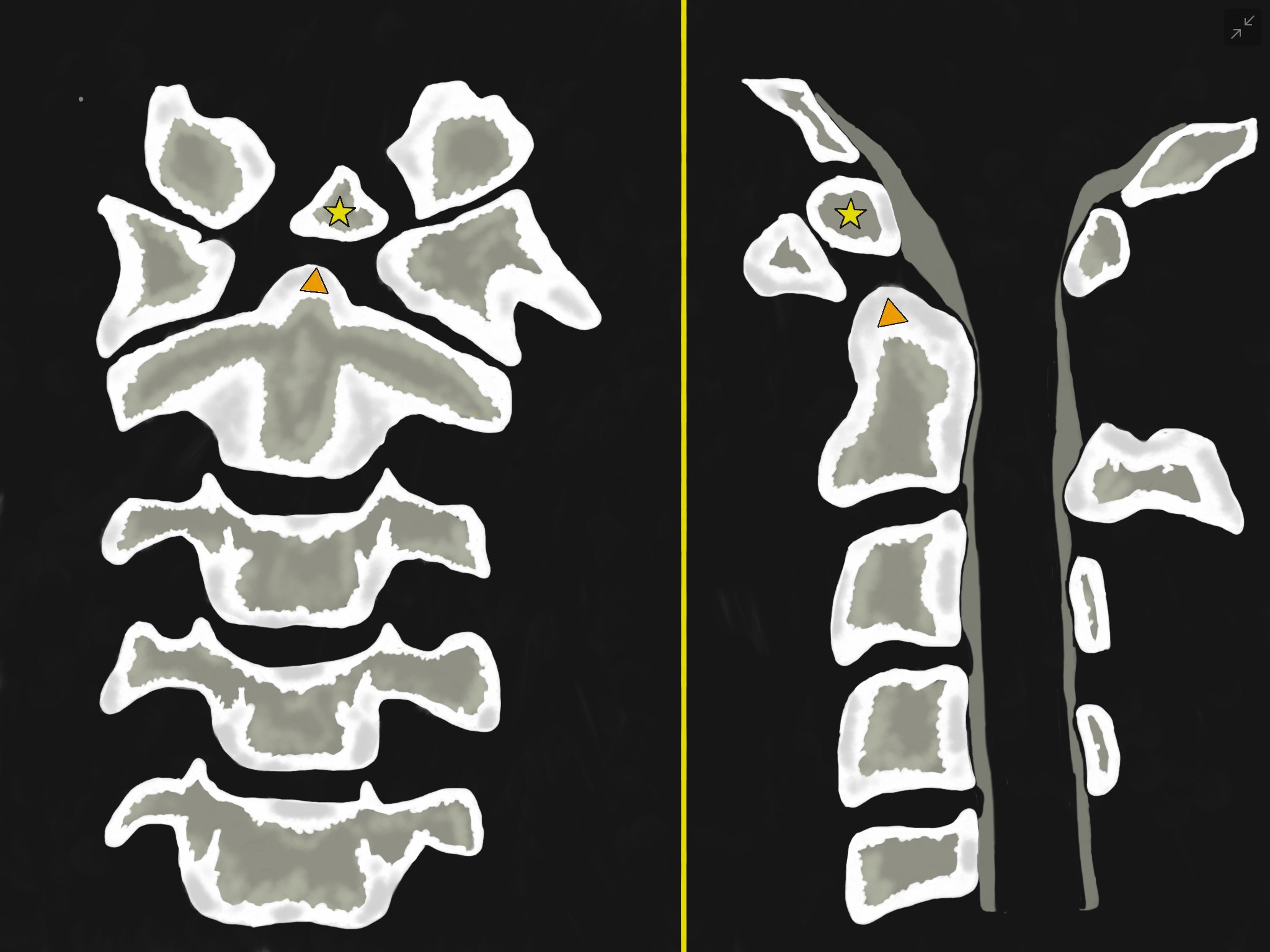

Os Odontoideum. Anteroposterior (left) and lateral (right) views demonstrate an oval or round ossicle with smooth circumferential cortical margins (yellow star), representing a hypoplastic odontoid process (orange triangle) that lacks continuity with the C2 vertebral body. It is often stabilized by the intact transverse ligament, which connects it to the anterior arch of C1.

Contributed by Franco De Cicco, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Lumbar Puncture Landmarks. This image shows the key structures encountered during a lumbar puncture for diagnostic, anesthetic, or therapeutic purposes. Labeled structures include L2, L5, the spinal cord, ligamentum flavum, supraspinous ligament, dura, and filum terminale. The needle is in the subarachnoid space at the L3-L4 level.

Contributed by S Bhimji, MD

References

Kaplan KM, Spivak JM, Bendo JA. Embryology of the spine and associated congenital abnormalities. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2005 Sep-Oct:5(5):564-76 [PubMed PMID: 16153587]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 29016431]

Nasser R, Yadla S, Maltenfort MG, Harrop JS, Anderson DG, Vaccaro AR, Sharan AD, Ratliff JK. Complications in spine surgery. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2010 Aug:13(2):144-57. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.SPINE09369. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20672949]

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, Kemper AR, Kubik M, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Phipps MG, Pignone M, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Tseng CW, Wong JB. Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018 Jun 26:319(24):2521-2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7498. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29946735]