Introduction

Spontaneous pneumothorax refers to the abnormal collection of gas in the pleural space between the lungs and the chest wall. Spontaneous pneumothorax occurs without an obvious etiology such as trauma or iatrogenic causes. Spontaneous pneumothorax can be classified as either primary or secondary. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) occurs when the patient does not have a history of the underlying pulmonary disease, whereas secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (SSP) is associated with a history of an underlying pulmonary disease. Patients may present with a variety of symptoms including tachycardia and dyspnea. A feared complication is tension pneumothorax. The diagnosis of spontaneous pneumothorax is based on clinical suspicion and can be confirmed with imaging. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax depends on multiple factors including the patient’s stability, the size of the pneumothorax, occurrence (i.e., first episode or recurrent), and the type of spontaneous pneumothorax (i.e., primary spontaneous pneumothorax or secondary spontaneous pneumothorax).[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

While primary spontaneous pneumothorax is not associated with underlying pulmonary disease, secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is associated with, but not limited to, the following:

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Asthma

- Cystic fibrosis

- Pneumonia (e.g., necrotizing, Pneumocystis jirovecii)

- Pulmonary abscess

- Tuberculosis

- Malignancy

- Interstitial lung disease (e.g., idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis)

- Connective tissue disease (e.g., Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis)

- Pulmonary infarct

- Foreign body aspiration

- Catamenial (i.e., associated with menses secondary to thoracic endometriosis)

- Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome

Epidemiology

Spontaneous pneumothorax occurs more frequently in adults than children and more frequently in males than females. In the United States, the adult incidence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax is estimated to be 7.4-18/100,000 population per year in males and 1.2-6.0/100,000 population per year in females, with similar rates of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax in males and females, 6.3 and 2.0, respectively, per 100,000 population per year. In children, the combined incidence of spontaneous pneumothorax is estimated to be 4.0/100,000 population per year in males and 1.1/100,000 population per year in females. Other risk factors include a history of smoking, and a tall, thin body habitus.[3][4]

Pathophysiology

The main principle of the pathophysiology of spontaneous pneumothorax revolves around gas leaking into the pleural space. Spontaneous pneumothorax is a multifactorial process and has been associated with rises in transpulmonary pressure and defects in the visceral pleura. Acute increases in alveolar pressure that exceed the pulmonary interstitial pressure can lead to alveolar rupture and pleural air leakage. Furthermore, points of weakness in the visceral pleura due to subpleural blebs, bullae, lung necrosis, and other connective tissue abnormalities can predispose the alveoli to rupture in both types of spontaneous pneumothorax, though the exact mechanism of how is not entirely understood. Intact bullae without an explicit defect in the visceral pleura have been shown to be associated with spontaneous pneumothorax; however, histopathological analyses and scanning electron microscopic studies of tissue obtained from thoracotomies suggest that sloughing of pleural mesothelial cells may play a significant role in the development of spontaneous pneumothorax.[5][6]

History and Physical

Spontaneous pneumothorax most commonly occurs at rest without a history of an exertional component. Patients are often complaining of sharp, pleuritic ipsilateral chest pain or acute dyspnea and increased work of breathing, especially patients with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. Tachycardia is one of the most common physical exam findings; however, in patients with smaller spontaneous pneumothorax (less than 15% of the hemithorax), the exam may be unremarkable. For patients with larger spontaneous pneumothorax (more than 15%), there may be reduced movement of the chest wall, ipsilateral decreased or absent breath sounds, jugular venous distension, pulsus paradoxus, hyperresonance on percussion, and decreased tactile fremitus. Development of a tension pneumothorax is a rare potential complication of spontaneous pneumothorax with the late, ominous findings of hypoxemia, hypotension, and tracheal deviation.

Evaluation

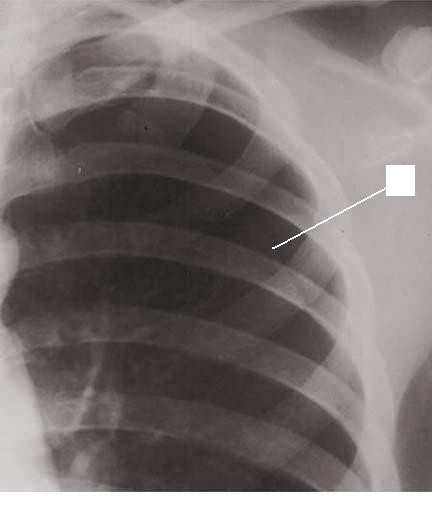

The diagnosis of spontaneous pneumothorax is often suggested by the patient’s history and physical exam findings, which can be confirmed by imaging. Chest radiography characteristically shows the displacement of the visceral pleural line with a space devoid of lung markings in between. While upright films are preferred, there is evidence that expiration does not necessarily increase the diagnostic yield. Ultrasound has also shown diagnostic potential. There is evidence that ultrasound has greater sensitivity than chest radiography; however, both modalities are limited in how well they estimate the size of a pneumothorax. The use of chest computed tomography (CT) for the diagnosis of spontaneous pneumothorax has been debated. The high sensitivity and specificity of CT can be of value when there is a high index of suspicion for spontaneous pneumothorax, and initial imaging is negative or equivocal. While arterial-blood gas measurements are not necessary for a diagnosis of spontaneous pneumothorax, they can be useful in assessing acute respiratory alkalosis and increases in the alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient when tension physiology is present.[7]

Treatment / Management

The main goal for the treatment of spontaneous pneumothorax is to evacuate the gas from the pleural space and the prevention of recurrences. The guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and the British Thoracic Society (BTS) are focused mainly on the management of pneumothorax in adults but not pediatric cases, specifically. Nevertheless, it is appropriate to initiate 100% oxygen via a non-rebreather mask and continuous cardiopulmonary monitoring for patients with spontaneous pneumothorax. Oxygen increases the rate of absorption of the gas from the pleural space up to four-fold compared to the absorption of 1% to 2% of the volume per day without oxygen. Clinically unstable patients with severe symptoms or symptoms suggestive of tension pneumothorax can be treated with emergent needle decompression as a bridge to tube thoracostomy placement.[8][9][10]

For stable patients presenting with a small primary spontaneous pneumothorax for the first time, conservative management with supplemental oxygen and observation of at least 6 hours is recommended. If repeat chest radiograph shows evidence of a stable pneumothorax and the patient has access to adequate follow-up, then the patient can be discharged with strict return precautions for a 24-hour recheck. The British Thoracic Society suggests that certain asymptomatic patients with large primary spontaneous pneumothorax may be considered for observation without active intervention. The American College of Chest Physicians recommends aspiration for large or symptomatic primary spontaneous pneumothorax with a small-bore catheter (14F or smaller) or, if the initial aspiration fails, admission with a chest tube (16F to 22F). Larger primary spontaneous pneumothorax can be further managed with video-assisted thoracoscopy surgery (VATS) or thoracotomy to perform bullectomy, pleurectomy, and mechanical pleurodesis (i.e., dry gauze abrasion). VATS is less invasive than thoracotomy and has been shown to be an effective measure in the treatment and prevention of spontaneous pneumothorax recurrence.

Patients with recurrent primary spontaneous pneumothorax should be admitted with thoracostomy tube placement as a bridge to VATS. In patients that are unwilling to undergo VATS, are poor surgical candidates, or are being managed in an institution where VATS is not readily available, chemical pleurodesis can be performed with the introduction of irritants such as tetracyclines (i.e., doxycycline, minocycline) or talc via the thoracostomy tube. The inflammatory processes associated with chemical pleurodesis lead to the formation of pleural adhesions that effectively obliterate the pleural space.

In adults presenting with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax, both the American College of Chest Physicians and the British Thoracic Society recommend admission with supplemental oxygen and repeat chest radiograph in small secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. The organizations also recommend placement of a pleural catheter or thoracostomy tube if the secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is large, the patient is symptomatic, or the secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is bilateral. Observation alone is not recommended as there is an increased risk for mortality in secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. Referral to a thoracic specialist is recommended, but not until the patient is stabilized with a chest drain.

Differential Diagnosis

- MI

- Aortic dissection

- Acute pericarditis

- Pulmonary embolism

- Rib & chest trauma

Pearls and Other Issues

The disposition of patients with spontaneous pneumothorax is multifactorial. For patients with a first-time episode of primary spontaneous pneumothorax that is small and asymptomatic, conservative measures can be a reasonable option. For patients with a first-time episode of primary spontaneous pneumothorax that is large and/or symptomatic, aspiration can be attempted as discussed in the treatment/management section; however, failure should prompt admission. It is recommended that all patients with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax regardless of the stability of the patient and the size of the pneumothorax should be admitted. Even with proper management, the recurrence rate for spontaneous pneumothorax is relatively high. Some studies estimate a recurrence rate of over 50% with the highest risk within the first 30 days. However, the rate of recurrence can be less than 5% after VATS with resection of blebs/bullae and pleurodesis.[3][11]

Special considerations should be made for patients who have travel plans due to risk for pneumothorax expansion. While some guidelines suggest that air travel should be delayed at least a week after radiographic evidence of pneumothorax resolution, there is no definite consensus among U.S. thoracic surgeons about the timeframe. Further investigation of the topic is warranted.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The majority of patients with a pneumothorax first present to the emergency department and hence the triage nurse, emergency room nurse and physician need to know about its presentation and treatment. The majority of simple and small pneumothorax can be managed conservatively without any treatment, as long as they are reliable in follow up. Repeat chest x-rays are required to ensure that the condition is resolving. Unlike the past, today, there are small portable pneumothorax kits which can be used to treat the disorder-the small size tubes are easy to insert and much less painful, compared to the chest tubes. When chest tubes are inserted, patients do not need admission. With spontaneous pneumothorax, there is a recurrence rate of 14-30% over three years. Recurrences are most common in smokers, patients with COPD and AIDs. In most patients, recurrences are treated with video-assisted thoracoscopy. Tension pneumothorax can occur in some patients and if not recognized can lead to death. Patients with a spontaneous pneumothorax should be urged to quit smoking and avoid air travel or travel to areas where medical care is not readily accessible. [12][13](Level V)

Media

References

Baig MA, Majeed MB, Attar BM, Khan Z, Demetria M, Gandhi SR. Efficacy and Safety of Indwelling Pleural Catheters in Management of Hepatic Hydrothorax: A Systematic Review of Literature. Cureus. 2018 Aug 6:10(8):e3110. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3110. Epub 2018 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 30338185]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOjeda Rodriguez JA, Hipskind JE. Iatrogenic Pneumothorax. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252313]

Hallifax RJ, Goldacre R, Landray MJ, Rahman NM, Goldacre MJ. Trends in the Incidence and Recurrence of Inpatient-Treated Spontaneous Pneumothorax, 1968-2016. JAMA. 2018 Oct 9:320(14):1471-1480. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14299. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30304427]

Savitsky E, Oh SS, Lee JM. The Evolving Epidemiology and Management of Spontaneous Pneumothorax. JAMA. 2018 Oct 9:320(14):1441-1443. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12878. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30304415]

Walker SP, Bibby AC, Halford P, Stadon L, White P, Maskell NA. Recurrence rates in primary spontaneous pneumothorax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The European respiratory journal. 2018 Sep:52(3):. pii: 1800864. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00864-2018. Epub 2018 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 30002105]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBertolaccini L, Congedo MT, Bertani A, Solli P, Nosotti M. A project to assess the quality of the published guidelines for managing primary spontaneous pneumothorax from the Italian Society of Thoracic Surgeons. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2018 Nov 1:54(5):920-925. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezy199. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29788194]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAguinagalde B, Aranda JL, Busca P, Martínez I, Royo I, Zabaleta J, Grupo de trabajo de la GPC para el Manejo de Pacientes con Neumotórax espontáneo. SECT Clinical practice guideline on the management of patients with spontaneous pneumothorax. Cirugia espanola. 2018 Jan:96(1):3-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2017.11.005. Epub 2017 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 29248330]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchnell J, Beer M, Eggeling S, Gesierich W, Gottlieb J, Herth FJF, Hofmann HS, Jany B, Kreuter M, Ley-Zaporozhan J, Scheubel R, Walles T, Wiesemann S, Worth H, Stoelben E. Management of Spontaneous Pneumothorax and Post-Interventional Pneumothorax: German S3 Guideline. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2019:97(4):370-402. doi: 10.1159/000490179. Epub 2018 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 30041191]

Wong A, Galiabovitch E, Bhagwat K. Management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax: a review. ANZ journal of surgery. 2019 Apr:89(4):303-308. doi: 10.1111/ans.14713. Epub 2018 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 29974615]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 28745853]

Santos C, Gupta S, Baraket M, Collett PJ, Xuan W, Williamson JP. Outcomes of an initiative to improve inpatient safety of small bore thoracostomy tube insertion. Internal medicine journal. 2019 May:49(5):644-649. doi: 10.1111/imj.14110. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30230151]

Sano A. Multidisciplinary team approach for complicated pneumothorax. Journal of thoracic disease. 2018 Jul:10(Suppl 18):S2109-S2110. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.06.94. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30123534]

Li X, Su X, Chen B, Yao H, Yu Y, Leng X, Lu Q, Wang C, Lei J, Ruetzler K, Fernando HC, Gilbert S, Yeung C, Filosso PL, Shen J, Zhu C, Written, AME Thoracic Surgery Collaborative Group. Multidisciplinary team approach on a case of bilateral tension pneumothorax. Journal of thoracic disease. 2018 Apr:10(4):2528-2536. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.04.81. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29850161]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence