Introduction

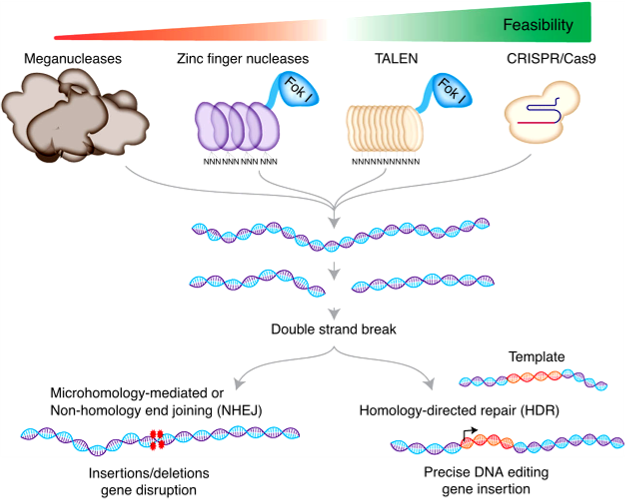

Mutagenesis is the process of an organism's deoxyribonucleic acids (DNA) change, resulting in a gene mutation. A mutation is a permanent and heritable change in genetic material, which can result in altered protein function and phenotypic changes. DNA consists of nucleotides that contain a phosphate backbone, a deoxyribose sugar, and 1 of 4 nitrogen-containing bases (adenine [A], guanine [G], cytosine [C], and thymine [T]). DNA mutagenesis occurs spontaneously in nature or as a result of mutagens (agents predisposing to alter DNA). Furthermore, molecular genetic techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), have revolutionized how mutations are obtained and studied. Mutagenesis is the driving force of evolution; however, it can also lead to cancers and heritable diseases (See Image. Genome Editing).[1]

Single base-pair substitutions are the most common cause of human pathology. An example is sickle cell disease, where a single base-pair mutation results in substituting glutamate to valine amino acid. Otherwise, human disease results from various insertions, deletions, duplications, inversions, expansions, fusions, and complex rearrangements. For example, a CGG repeat expansion in the FRM1 gene causes fragile X syndrome, while a fusion protein BCR-ABL results in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).[2][3]

Biochemical

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Biochemical

It is noteworthy that not all DNA mutations have an impact on protein synthesis or function. There are various mutations, such as silent, missense, nonsense, and frameshifts.

A silent mutation is a nucleotide substitution that codes for the same amino acid; therefore, there is no change in the amino acid sequence or protein function.

A missense mutation occurs when a nucleotide substitution changes an amino acid. Missense mutations have variable effects but can lead to a decreased or altered protein function (eg, sickle cell disease).[4]

A nonsense mutation is when a nucleotide substitution results in a new stop codon, which includes UGA, UAA, and UAG (remember the mnemonic "U Go Away, U Are Away, and U Are Gone," respectively). These protein products are truncated and frequently nonfunctional (eg, cystic fibrosis).[5]

A frameshift mutation occurs by adding or deleting nucleotides not divisible by 3, resulting in the misreading of the downstream nucleotides. These proteins may be shorter or longer, and protein function may be disrupted or altered (eg, Duchenne muscular dystrophy).[6]

Other types of mutations exist outside of the coding sequence. These include splice site, promoter or enhancer sequence, and termination site mutations. For example, in some forms of B-thalassemia, a mutated splice site uses cryptic splice locations, causing impaired B-globin synthesis.[7]

Function

Mutagenesis is the driving force behind evolution and genetic variation results from mutations. Any change in genetic information may result in advantageous or disadvantageous phenotypic characteristics that impact an organism's fitness. When a mutation results in a higher fitness, natural selection favors these phenotypes, and these traits are more likely to be passed to offspring.[8]

Mechanism

Mutagenesis occurs due to DNA replication errors, damage, and lab techniques. Here, we break mutagenesis down into endogenous and exogenous causes.

Endogenous

- Errors in DNA replication: Our body possesses high and low-fidelity DNA polymerases. Although the error rate is minimal, high-fidelity polymerases and mismatch repair (MMR) mechanisms still make 1 in 10^6 to 10^8 base substitution per cell per generation. Furthermore, some errors occur due to replication slippage at repetitive sequences, which can lead to insertions and deletions. A mutation results if these errors are not repaired before the next round of DNA replication.[9][10]

- Errors in DNA repair mechanisms: The DNA damage response (DDR) is a group of mechanisms that sense DNA —errors and promote repair. Errors in repair or mutations affecting the DDR network cause different cancers. There are multiple DNA repair mechanisms, including MMR, base excision repair (BER), nucleotide excision repair (NER), translesion synthesis (TLS), homologous recombination (HR), and nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathways. A cell is predisposed to DNA damage if these repair mechanisms disappear. For example, xeroderma pigmentosum (a rare autosomal recessive skin disorder that makes a person highly prone to developing skin cancer) is caused by a mutation in the NER pathway, resulting in a build-up of UV-associated damage. The TLS repair system and NHEJ are of interest to endogenous mutagenesis. During DNA replication, high-fidelity polymerases have difficulty passing damaged bases (eg, pyrimidine dimers or crosslinked DNA), which stalls DNA replication. Failure to restart replication can result in double-stranded breaks, chromosomal rearrangements, and cell death. Therefore, it is often beneficial to circumvent these replicative arrests to promote cell survival. One mechanism to accomplish this is the TLS system. TLS involves DNA polymerases with larger active sites that allow them to tolerate and bypass DNA lesions. However, it comes at the expense of lower replication fidelity and high error rates, resulting in a greater likelihood of base substitutions.[10] Otherwise, NHEJ is a repair mechanism for double-stranded DNA breaks. It brings 2 ends of DNA fragments together and doesn't require homologous sequences. Therefore, this can result in deletions and insertions.[11]

- Spontaneous base deamination: Base deamination is when a nucleotide base loses an amine group, effectively changing the nucleotide. The following are major deamination reactions: cytosine to uracil (U), adenine to hypoxanthine, guanine to xanthine, and 5-methyl cytosine (5mC) to thymine. If these alterations are not repaired, there can be a change in the DNA sequence. For example, if cytosine deaminates to uracils, there are new A:T mutations in 2 replication events. This G:C to A:T transition accounts for 33% of the single-site mutations resulting in human hereditary diseases.[10]

- Oxidative DNA damage: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a byproduct of the electron transport chain (ETC) and other cellular processes in normal cell physiology. ROS serves essential cellular roles, including redox signaling and immune defense. However, in high quantities, ROS damages a cell and its DNA. There have been 100 different oxidative base lesions and 2-deoxyribose modifications described. One example is the oxidation of carbon #8 of guanine, forming 8-oxoguanine (8-OG). 8-OG incorrectly pairs with adenine (instead of cytosine), resulting in a G:C to A:T transition. Excess ROS are known to be associated with many diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, cancer, and heart failure.[10]

- Base methylation: S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) is used as a methyl donor during physiologic DNA methylation. At a concentration of 4x10^-5M, SAM can generate over 4,000 methylated base changes per cell per day. The significance of this can be depicted in the methylated products O6-methylguanine and O4-methylamine. These highly mutagenic products result in G:C to A:T and T:A to C:G transition mutations.[10][12]

- Abasic sites (ie, apurinic and apyrimidinic sites): Approximately 10,000 abasic sites are made daily by spontaneous hydrolysis or DNA glycosylase cleavage. Abasic sites are unstable and commonly removed by endonucleases. In other cases, they are repaired by TLS polymerases. If these damage sites are not corrected, they may result in mutagenesis.[10][13]

Exogenous

- Ionizing radiation (IR): IR comes from the soil, radon, medical devices, and cosmic radiation, among others. It can damage DNA directly (eg, DNA strand breaks) or indirectly (eg, radiolysis of water molecules producing ROS). Ionizing radiation can generate a range of nucleotide base lesions, similar to that discussed for ROS, resulting in mutagenesis.[10]

- Ultraviolet (UV) radiation: UV light falls between 100 to 400 nm, with the most harmful radiation at lower wavelengths—UV light damages DNA through direct and indirect energy transfer (to nearby molecules. The 2 main products of UV damage are pyrimidine dimers and pyrimidine pyrimidone photoproducts. These byproducts distort the DNA helix, requiring the NER system or the error-prone TLS polymerases to bypass them. Pyrimidine dimers cause C:G to T:A, T:A to C:G, and tandem CC to TT transition mutations.[10]

- Alkylating agents & Aromatic amines: Alkylating agents (eg, nitrogen mustard gas, methyl methanesulfonate [MMS], ethyl methanesulfonate [EMS], N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea [ENU]) have a high affinity for nitrogens on nucleotide bases, mainly N3 of adenine and N7 of guanine. MMS, for example, reacts with adenine and guanine to produce N3-methyladenine and N7-methylguanine, respectively. These methyl products are susceptible to N-glycosidic bond cleavage that can create abasic sites. Aromatic amines (eg, 2-aminofluorene, previously used in insecticides) are metabolized by the CYP450 system and converted into alkylating agents. These products primarily cause lesions to the C8 position of guanine. C8-guanine lesions are known to give rise to base substitutions and frameshift mutations.[10]

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH): PAHs (eg, dibenzo[a,l]pyrene, naphthalene, anthracene, and pyrene) are carbon compounds with 2 or more aromatic rings. They are commonly present in tobacco smoke, automobile exhaust, charred food, and combustion products of fossil fuels and organic matter. The CYP450 enzymes convert PAHs into reactive DNA intermediates that intercalate into DNA, ultimately forming a DNA adduct (a segment of DNA bound to a cancer-causing chemical). This results in DNA damage and, thus, can cause mutagenesis.[10]

- Crosslinking: Crosslinking occurs when 2 nucleotides form a covalent link. Agents commonly associated with crosslinking include cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and psoralens. Interstrand crosslinking blocks DNA replication, and this requires repair or bypassing. TLS is one of these repair mechanisms and is associated with high substitution rates.[10][14]

- Insertional mutagenesis: This is the process by which exogenous DNA integrates into host DNA. Insertional mutagenesis can be natural, mediated by transposons or viruses, or accomplished in a laboratory. Given there is an addition of nucleotides, insertional mutagenesis commonly results in frameshift mutations.[15]

- Other toxins: Aflatoxin is a naturally occurring toxin from Aspergillus. The CYP450 system metabolizes aflatoxin into an active form that adducts with N7 of guanine, which results in depurination. Aflatoxin is a well-established liver carcinogen that is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. N-nitrosamines are organic compounds commonly found in tobacco smoke, preserved meats, and the environment. The CYP450 system metabolizes them to form DNA alkylating agents. N-nitrosamines have been implicated in nasopharyngeal, esophageal, and gastric.[10][16]

- Laboratory techniques: Different laboratory techniques, including PCR, non-PCR, and gene-editing tools, induce mutagenesis. These are discussed further in the "Testing/Methods" section below.

Testing

Mutagenesis is a technique used in molecular biology to create mutant genes, proteins, and organisms. Two primary mutagenesis techniques are site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) and random-and-extensive mutagenesis (REM). These methods are accomplished mainly by primarily conducted (PCR) and non-polymerase chain reactions (non-PCR). Other mutagenesis performing/Cas9 technology methods are TALENs (transcription activator-like effector nucleases) and Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFN).

Site-directed Mutagenesis

SDM is a technique where DNA can be modified at a specific nucleotide location, causing a predetermined amino acid change. These substitution mutations can result in drastic changes in protein conformation and function. This technique requires (1) a DNA template with a target gene, (2) knowledge of the target gene's nucleotide sequence, and (3) a short primer (commonly 20 to 30 base pairs) complementary to the target sequence that is modified to contain a mismatched nucleotide (typically 1 to 3 base pairs that cause an amino acid change). The general procedure for SDM is the following:

- Step 1: Separation of the 2 strands of template DNA. This can be accomplished by heat or an alkali solution.

- Step 2: Addition of the modified DNA primer. Once the DNA primer anneals with a single strand, a DNA polymerase replicates the strand.

- Step 3: The second round of replication yields a mutant DNA strand that can be used to synthesize a modified protein.

Techniques for Performing SDM

PCR and non-PCR techniques are in vitro methods for performing SDM. In vitro synthesis has 4 essential components: DNA template, modified primers, deoxyribonucleic nucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs [ie, dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP]), and DNA polymerase (thermostable or thermolabile). The polymerase chain reaction technique utilizes thermostable DNA polymerases (eg, Taq, Pfu, and Vent), at least 2 primers, and multiple heating and cooling cycles (average 30 cycles). Each cycle has 3 phases: denaturation (approximately 95 degrees Celsius), annealing (about 55 degrees Celsius), and extension (about 72 degrees Celsius). The denaturation phase separates the template DNA molecule into 2 single-stranded molecules. The annealing phase is when the modified primer base pairs at the sequence of interest. Lastly, the extension phase extends the annealed primers according to the template strand. The advantage of PCR is that it works more favorably with different DNA templates (ie, single or double-stranded DNA and GC-rich regions) and produces millions of copies of a target gene. The disadvantage is there is less sequence fidelity (ie, thermostable polymerases are more error-prone than thermolabile polymerases). The non-polymerase chain reaction technique utilizes thermolabile DNA polymerases, 1 primer, and a constant reaction temperature (eg, 37 degrees Celsius). The DNA template is denatured with an alkali solution or heat in this strategy. The template is annealed with the modified primer, and DNA synthesis occurs at 37 degrees Celsius. Though single or double-stranded DNA templates can be used, more favorable outcomes occur if a single-stranded DNA template is used (this increases the success of annealing). This process produces a hybrid DNA molecule (ie, 1 template strand and 1 newly synthesized mutant strand), which can be transformed or infected into E. coli. Once in E.coli, the mutant DNA and wild-type DNA can be segregated. Non-PCR has greater sequence fidelity than the PCR method; however, only 1 DNA strand is generated (rather than millions).[17]

Screening for Desired Mutants in SDM

There are different methods for selecting and screening for desired mutants. One of the PCR approaches is to use plasmids grown in E. coli dam methylated) and contain a gene for antibiotic resistance. As discussed, modified forward and reverse primers are extended around plasmid DNA, creating copies of the template with the inserted mutations. Since the original parental template strand is methylated, a restriction endonuclease Dpn I - specific for methylated and hemimethylated DNA - digests this DN, A leaving only the mutant plasmid, which is further amplified. The plasmid is transformed into E.coli, and bacteria are grown on media that contain the appropriate antibiotic for the plasmid. One can then pick single colonies and grow them overnight to isolate the mutant plasmid DNA. Please refer to the article by Bachman for a more detailed review.[18] Since there is the possibility of random mutations in PCR and non-PCR methods, sequencing should be performed to verify the desired mutation was made. DNA sequencing technology (eg, Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing) can be utilized to determine nucleotide sequences.[19]

Random and Extensive Mutagenesis

REM is a useful approach when many mutations are desired; however, there is less control over the resulting modifications. This technique has helped map out critical residues of proteins (eg, EcoRV restriction endonuclease). REM can be accomplished through different methods:

- Primers randomly produced with mismatched bases. This technique synthesizes a set of mutagenic primers with 3 mismatched bases at a single base position in the same reaction. These sets of primers are then used to synthesize mutant DNA with 3 different mutations at the same base position. Other than this, a primer can be synthesized using an ambiguous base (eg, deoxyinosine), capable of base-pairing with varying dNTPs. In theory, there is a 75% probability a wrong base pairs with this ambiguous base, which generates mutations in subsequent rounds of replication.

- Erroneous PCR. Taq DNA polymerase typically has lower fidelity than other polymerases (eg, Pfu and Vent). Furthermore, altering external conditions, such as buffer composition (eg, high pH or high magnesium concentration), can affect the frequency of errors. Under various combinations of external conditions, the error rate of Taq PCR can be increased to 1 in 150 base pairs from 1 in 633.

- Use of ambiguous base analogs (eg, deoxyinosine). As already stated, deoxyinosine triphosphate (dI) can base pair with different dNTPs. In a reaction that contains dI and adjusted dNTPs concentrations (eg, typical levels of 3 dNTPs and low levels of the fourth dNTP), a dI is likely to be incorporated into the newly synthesized sequence. Theoretically, there is a 75% chance that a wrong base pairs with a dI during subsequent replication events. This technique can result in 1 in 250 base pair mutation rates.[17]

- Use of mutagenic agents. A classic method for causing widespread random mutations is exposing a cell or organism to a mutagen (eg, ENU).[20]

Insertions and Deletions

PCR is effective at producing insertions or deletions. Small insertions or deletions (less than 10 base pairs) can occur by utilizing the modified primer design described above. Large deletions can occur by joining 2 PCR-amplified fragments, which omit a portion of a DNA fragment. Large insertions can occur using megaprimers or overlap-extension PCR.[17]

CRISPR-Cas9

This genome-editing technology is derived from bacterial defenses against viruses and foreign plasmids. It has 2 vital components: a guide RNA (gRNA) that binds in a complementary way to a target DNA sequence and an endonuclease (Cas9) that causes a dsDNA break that requires repair. Cas9-induced site-specific dsDNA breaks induce endogenous cell repair mechanisms, which can be exploited to modify DNA. The error-prone nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) can rapidly ligate DNA breaks; however, it may generate small insertions and deletions that can cause frameshift mutations. Alternatively, dsDNA breaks can be repaired by homology-directed repair (HDR), which can insert exogenous DNA and introduce precise genome editing.[21]

TALENS vs. Zinc Finger Nucleases

TALENs and ZFN are gene-editing tools with similar principles; however, they have different underlying designs. They both are proteins that consist of DNA binding domains (ie, TALE proteins vs. zinc fingers domains) and DNA cleavage domains (eg, Fok1). DNA specificity resides in the TALE proteins and the zinc finger domains. For cleavage to occur, the restriction enzyme must dimerize; therefore, at least 2 proteins are needed per target DNA. A double-stranded DNA break is made once dimerization occurs at a target location. Similar to CRISPR, this is repaired by NHEJ (with the possibility of insertions and deletions) or homologous recombination (where exogenous DNA can be added). A key difference between TALENs and ZFN is that TALE proteins recognize a single base, while zinc finger domains recognize 3 or 4 bases. Given that zinc fingers must recognize multiple bases, it may reduce DNA specificity compared to TALE proteins.[22][23]

Clinical Significance

Mutagenesis has multiple implications in clinical medicine. This topic discusses a few, including carcinogenesis, heritable diseases, microorganism resistance, large-scale mutagenic projects, and precision medicine.

Carcinogenesis (i.e., tumorigenesis or oncogenesis) is when a cell begins to divide uncontrollably. Mutations of oncogenes (which promote cell growth), tumor suppressor genes (which inhibit cell growth), or cell-cycle genes (which regulate the cell cycle) can generate a clonal cell population with highly proliferative properties, leading to cancer.[24] Approximately two-thirds of cancer driver mutations are attributable to spontaneous mutagenesis that occurs during normal DNA replication.[25] Furthermore, multiple agents (such as those described in the "mechanism" section) are known to be associated with carcinogenesis. Tobacco contains DNA methylating agents, alkylating agents, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and N-nitrosamines. Smoking tobacco is proven to increase the risk of a multitude of cancers, including lung, colorectal, head and neck, and lower urinary tract cancers. Tobacco accounts for 16% of all cancer diagnoses and approximately one-third of all cancer deaths in the US. This highlights why counseling on smoking cessation and other preventative health measures becomes so important.[10][24][26]

Ionizing radiation (IR), as a consequence of atomic radiation (eg, Chernobyl) or iatrogenic causes, is associated with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), among others. In PTC, IR increases the rate of DNA rearrangements that cause a permanently active promotor region of ret, a tyrosine kinase. This has been associated with the pathogenesis of PTC. Applying this knowledge, anti-promoter agents may one day be a method for future PT therapy.[27] Interestingly, some chemotherapeutic drugs used to combat cancers - in particular, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide - are themselves carcinogenic. These drugs have been implicated in the development of tumor resistance and subsequent cancer development. Therefore, care should be taken when choosing treatment regimens, especially in childhood cancers.[28]

Heritable diseases originate in mutagenesis, as these are permanent DNA changes passed to offspring. Some examples of hereditary diseases include sickle cell disease, Tay-Sachs disease, cystic fibrosis, Huntington disease, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and hemophilia, among many others. A well-studied example is sickle cell anemia. This autosomal recessive disease results from a missense mutation in the B-globin gene (ie, a point mutation resulting in a glutamic acid to valine substitution). Research shows this mutation created an adaptive advantage in heterozygote carriers in malaria-endemic areas.[29] However, homozygous inheritance has a poor prognosis due to increased risk for anemia, infection, stroke, and organ damage.[30]

Drug resistance in microorganisms is a result of mutagenesis. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms are associated with increased antibiotic use. MDR organisms have increased mortality rates, and it is estimated that by 2050, there might be 300 million premature deaths worldwide due to MDR organisms. This highlights the need to practice effective antimicrobial stewardship to slow the development of MDR organisms.[31] An interesting example of drug resistance can occur in the treatment of Chagas disease. Benznidazole is a front-line pro-drug used in Chagas treatment. New evidence suggests that Trypanosoma cruzi may process this drug into metabolites that cause whole-genome mutations. Therefore, this may be a reason for treatment failure and the development of drug-resistant parasites. This can even lead to resistance to different classes of drugs, like posaconazole, used in combination therapy of Trypanosoma cruzi. Therefore, vigilance is required when using benznidazole in combination therapy.[32]

Large-scale mutagenesis techniques can map functional amino acid residues that affect particular phenotypes. For example, a mouse study on the Golgi protein GMAP-210 showed that gene alteration caused a phenotype that resembled human achondrogenesis type 1A. This helped lead to the discovery of a similar mutation found in humans.[33]

Lastly, precision medicine (PM) is a concept where disease treatment is based on knowing an individual's genome abnormalities, which became relevant as whole-genome sequencing became more accessible. PM depends on new therapeutic strategies, drug development, and gene-oriented treatment.[34] For example, gene-targeted techniques like CRISPR/Cas9 and TALENs may one day have clinical use. CRISPR is being investigated to treat single-gene mutations (eg, DMD, cystic fibrosis), HIV, and cancers.[35] PM still has multiple challenges, such as validating functional mechanisms of mutated gene expression.[34] However, PM may one day have an essential impact on disease cures.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Genome Editing. A Schematic of using meganuclease, zinc finger nuclease, TALEN, and CRISPR nucleases for genome editing. The different generations of genome editing and DNA repair pathways are used to modify target DNA.

Mazhar Adli, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Zhang L, Vijg J. Somatic Mutagenesis in Mammals and Its Implications for Human Disease and Aging. Annual review of genetics. 2018 Nov 23:52():397-419. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120417-031501. Epub 2018 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 30212236]

Cooper DN. Human gene mutation in pathology and evolution. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2002 May:25(3):157-82 [PubMed PMID: 12137225]

Ayatollahi H, Keramati MR, Shirdel A, Kooshyar MM, Raiszadeh M, Shakeri S, Sadeghian MH. BCR-ABL fusion genes and laboratory findings in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in northeast Iran. Caspian journal of internal medicine. 2018 Winter:9(1):65-70. doi: 10.22088/cjim.9.1.65. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29387322]

Ribeil JA,Hacein-Bey-Abina S,Payen E,Magnani A,Semeraro M,Magrin E,Caccavelli L,Neven B,Bourget P,El Nemer W,Bartolucci P,Weber L,Puy H,Meritet JF,Grevent D,Beuzard Y,Chrétien S,Lefebvre T,Ross RW,Negre O,Veres G,Sandler L,Soni S,de Montalembert M,Blanche S,Leboulch P,Cavazzana M, Gene Therapy in a Patient with Sickle Cell Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 28249145]

McHugh DR, Steele MS, Valerio DM, Miron A, Mann RJ, LePage DF, Conlon RA, Cotton CU, Drumm ML, Hodges CA. A G542X cystic fibrosis mouse model for examining nonsense mutation directed therapies. PloS one. 2018:13(6):e0199573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199573. Epub 2018 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 29924856]

Tabebordbar M, Zhu K, Cheng JKW, Chew WL, Widrick JJ, Yan WX, Maesner C, Wu EY, Xiao R, Ran FA, Cong L, Zhang F, Vandenberghe LH, Church GM, Wagers AJ. In vivo gene editing in dystrophic mouse muscle and muscle stem cells. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2016 Jan 22:351(6271):407-411. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5177. Epub 2015 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 26721686]

Atweh GF, Anagnou NP, Shearin J, Forget BG, Kaufman RE. Beta-thalassemia resulting from a single nucleotide substitution in an acceptor splice site. Nucleic acids research. 1985 Feb 11:13(3):777-90 [PubMed PMID: 2987809]

Lenski RE. What is adaptation by natural selection? Perspectives of an experimental microbiologist. PLoS genetics. 2017 Apr:13(4):e1006668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006668. Epub 2017 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 28426692]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKunkel TA. Evolving views of DNA replication (in)fidelity. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. 2009:74():91-101. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2009.74.027. Epub 2009 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 19903750]

Chatterjee N, Walker GC. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 2017 Jun:58(5):235-263. doi: 10.1002/em.22087. Epub 2017 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 28485537]

Heidenreich E, Novotny R, Kneidinger B, Holzmann V, Wintersberger U. Non-homologous end joining as an important mutagenic process in cell cycle-arrested cells. The EMBO journal. 2003 May 1:22(9):2274-83 [PubMed PMID: 12727893]

De Bont R, van Larebeke N. Endogenous DNA damage in humans: a review of quantitative data. Mutagenesis. 2004 May:19(3):169-85 [PubMed PMID: 15123782]

Chan K, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA. The choice of nucleotide inserted opposite abasic sites formed within chromosomal DNA reveals the polymerase activities participating in translesion DNA synthesis. DNA repair. 2013 Nov:12(11):878-89. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.07.008. Epub 2013 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 23988736]

Shen X, Li L. Mutagenic repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 2010 Jul:51(6):493-9. doi: 10.1002/em.20558. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20209624]

Ranzani M, Annunziato S, Adams DJ, Montini E. Cancer gene discovery: exploiting insertional mutagenesis. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2013 Oct:11(10):1141-58. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0244. Epub 2013 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 23928056]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarlson ES, Upadhyaya P, Hecht SS. A General Method for Detecting Nitrosamide Formation in the In Vitro Metabolism of Nitrosamines by Cytochrome P450s. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2017 Sep 25:(127):. doi: 10.3791/56312. Epub 2017 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 28994777]

Ling MM, Robinson BH. Approaches to DNA mutagenesis: an overview. Analytical biochemistry. 1997 Dec 15:254(2):157-78 [PubMed PMID: 9417773]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBachman J. Site-directed mutagenesis. Methods in enzymology. 2013:529():241-8. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-418687-3.00019-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24011050]

Behjati S, Tarpey PS. What is next generation sequencing? Archives of disease in childhood. Education and practice edition. 2013 Dec:98(6):236-8. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304340. Epub 2013 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 23986538]

Stottmann R, Beier D. ENU Mutagenesis in the Mouse. Current protocols in human genetics. 2014 Jul 14:82():15.4.1-15.4.10. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg1504s82. Epub 2014 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 25042716]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHryhorowicz M, Lipiński D, Zeyland J, Słomski R. CRISPR/Cas9 Immune System as a Tool for Genome Engineering. Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis. 2017 Jun:65(3):233-240. doi: 10.1007/s00005-016-0427-5. Epub 2016 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 27699445]

Hegazy WA, Youns M. TALENs Construction: Slowly but Surely. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2016:17(7):3329-34 [PubMed PMID: 27509972]

Jabalameli HR, Zahednasab H, Karimi-Moghaddam A, Jabalameli MR. Zinc finger nuclease technology: advances and obstacles in modelling and treating genetic disorders. Gene. 2015 Mar 1:558(1):1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.044. Epub 2014 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 25536166]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBasu AK. DNA Damage, Mutagenesis and Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018 Mar 23:19(4):. doi: 10.3390/ijms19040970. Epub 2018 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 29570697]

Tomasetti C, Li L, Vogelstein B. Stem cell divisions, somatic mutations, cancer etiology, and cancer prevention. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2017 Mar 24:355(6331):1330-1334. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf9011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28336671]

Andreotti G, Freedman ND, Silverman DT, Lerro CC, Koutros S, Hartge P, Alavanja MC, Sandler DP, Freeman LB. Tobacco Use and Cancer Risk in the Agricultural Health Study. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2017 May:26(5):769-778. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0748. Epub 2016 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 28035020]

Sarasin A, Bounacer A, Lepage F, Schlumberger M, Suarez HG. Mechanisms of mutagenesis in mammalian cells. Application to human thyroid tumours. Comptes rendus de l'Academie des sciences. Serie III, Sciences de la vie. 1999 Feb-Mar:322(2-3):143-9 [PubMed PMID: 10196666]

Szikriszt B, Póti Á, Pipek O, Krzystanek M, Kanu N, Molnár J, Ribli D, Szeltner Z, Tusnády GE, Csabai I, Szallasi Z, Swanton C, Szüts D. A comprehensive survey of the mutagenic impact of common cancer cytotoxics. Genome biology. 2016 May 9:17():99. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0963-7. Epub 2016 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 27161042]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNaik RP, Haywood C Jr. Sickle cell trait diagnosis: clinical and social implications. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2015:2015(1):160-7. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.160. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26637716]

Meremikwu MM, Okomo U. Sickle cell disease. BMJ clinical evidence. 2016 Jan 22:2016():. pii: 2402. Epub 2016 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 26808098]

Munita JM, Arias CA. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance. Microbiology spectrum. 2016 Apr:4(2):. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0016-2015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27227291]

Campos MC, Phelan J, Francisco AF, Taylor MC, Lewis MD, Pain A, Clark TG, Kelly JM. Genome-wide mutagenesis and multi-drug resistance in American trypanosomes induced by the front-line drug benznidazole. Scientific reports. 2017 Oct 31:7(1):14407. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14986-6. Epub 2017 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 29089615]

Smits P, Bolton AD, Funari V, Hong M, Boyden ED, Lu L, Manning DK, Dwyer ND, Moran JL, Prysak M, Merriman B, Nelson SF, Bonafé L, Superti-Furga A, Ikegawa S, Krakow D, Cohn DH, Kirchhausen T, Warman ML, Beier DR. Lethal skeletal dysplasia in mice and humans lacking the golgin GMAP-210. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Jan 21:362(3):206-16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900158. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20089971]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang X. Gene mutation-based and specific therapies in precision medicine. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2016 Apr:20(4):577-80. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12722. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26994883]

Redman M, King A, Watson C, King D. What is CRISPR/Cas9? Archives of disease in childhood. Education and practice edition. 2016 Aug:101(4):213-5. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310459. Epub 2016 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 27059283]