Introduction

Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is a life-threatening condition that occurs when a blood clot that has arisen from a different area obstructs the pulmonary arteries. Most commonly, PE originates from a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the lower extremities. PE usually occurs when a part of this thrombus breaks off and enters the pulmonary circulation. PE rarely occurs from embolizing other materials into the pulmonary circulation, eg, air, fat, or tumor cells.[1] Together, PE and DVT comprise venous thromboembolism (VTE), a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Risk factors for PE include genetic predispositions like thrombophilia and acquired conditions, including prolonged immobility, surgery, and malignancy.

Despite advancements in diagnostic tools and treatment options, the nonspecific symptoms of PE (eg, dyspnea, chest pain, and syncope) often overlap with other cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, making timely diagnosis challenging for clinicians. Prompt recognition and management of PE are critical, as delayed intervention can lead to severe complications, including hemodynamic instability, right ventricular failure, and sudden death. Risk stratification tools such as the Wells criteria and Geneva score, alongside diagnostic imaging, are essential for accurate diagnosis. However, the underutilization of these tools, coupled with variations in therapeutic approaches, underscores the need for standardized clinical protocols. Clinicians can improve patient outcomes through enhanced knowledge and proficiency in identifying risk factors, employing diagnostic strategies, and initiating evidence-based treatments.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Risk Factors for Pulmonary Embolism

Most PEs originate as lower extremity DVTs. Hence, PE risk factors are the same as DVT. The Virchow triad of hypercoagulability, venous stasis, and endothelial injury provides an understanding of these risk factors.

Risk factors can be classified as genetic and acquired. Genetic risk factors include thrombophilia, eg, factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin gene mutation, protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, and hyperhomocysteinemia. Acquired risk factors include immobilization for prolonged periods (eg, bed rest of longer than 3 days, any type of travel for >4 hours), recent orthopedic surgery, malignancy, indwelling venous catheter, obesity, pregnancy, cigarette smoking, and oral contraceptive pill use.[2][3][4][5] Smoking is a risk factor for all causes of pulmonary infarction, including those associated with PE.[6] Paradoxically, younger age (peaking at 40) and increased height are associated with an increased likelihood of developing a PE complicated by pulmonary infarction, while obesity is associated with a reduced likelihood.[7]

Other predisposing factors for VTE include:

- Fracture of lower limb

- Hospitalization for heart failure or atrial fibrillation/flutter within the previous 3 months

- Hip or knee replacement

- Major trauma

- History of previous venous thromboembolism

- Central venous lines

- Chemotherapy

- Congestive heart failure or respiratory failure

- Hormone replacement therapy

- Oral contraceptive therapy

- Postpartum period

- Infection (specifically pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and HIV)

- Cancer (highest risk in metastatic disease)

- Thrombophilia

- Bed rest longer than 3 days

- Obesity

- Pregnancy

Cancer carries a high risk for thrombus formation and, hence, PE. Pancreatic cancer, hematological malignancies, lung cancer, gastric cancer, and brain cancer carry the highest risk for VTE.[8] Infection anywhere in the body is a common trigger for VTE.[9] Myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure increase the risk of PE. Patients with VTE have an increased risk of subsequent stroke and myocardial infarction.[10][11]

Types of Pulmonary Embolism

Categorizing PE based on the presence or absence of hemodynamic stability is crucial. Hemodynamically unstable PE, previously called massive or high-risk PE, is PE that results in hypotension as defined by systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or a drop in systolic blood pressure of ≥40 mm Hg from baseline or hypotension that requires vasopressors or inotropes), the old term "massive" PE does not describe the size of the PE but rather the hemodynamic effect. Patients with a hemodynamically unstable PE are more likely to die from obstructive shock (ie, severe right ventricular failure).

Hemodynamically stable PE is a spectrum ranging from small, mildly symptomatic, or asymptomatic PE (low-risk PE or small PE) to PEs that cause mild hypotension that stabilizes in response to fluid therapy or those that present with right ventricular dysfunction (submassive or intermediate-risk PE) but are hemodynamically stable.

Epidemiology

Acute PE incidence ranges from 39 to 115 per 100,000 population annually; for DVT, the incidence ranges from 53 to 162 per 100,000 people.[12] After coronary artery disease and stroke, acute PE is the third most common type of cardiovascular disease.[13] Furthermore, the incidence of acute PE is higher in males than females.[14] PE complicated by pulmonary infarction occurs at a rate of 16% to 31%.[7]

Overall, PE-related mortality is high, and in the United States, PE causes 100,000 deaths annually.[14] However, the mortality rates attributable to PE are challenging to estimate accurately because many patients with sudden cardiac death are thought to have had a thromboembolic event like PE. The case-fatality rates of PE have decreased, likely due to improved diagnostic methods, early interventions, and therapies.

Pathophysiology

PE occurs when a blot clot enters the pulmonary circulation. Multiple emboli are typically involved within the lower lung lobes more frequently than the upper lobes; bilateral lung involvement is also more common.[15] Large emboli tend to obstruct the main pulmonary artery, causing saddle embolus with deleterious cardiovascular consequences. In contrast, smaller-sized emboli block the peripheral arteries and can lead to pulmonary infarction, manifested by intra-alveolar hemorrhage.

PE leads to impaired gas exchange due to obstruction of the pulmonary vascular bed, leading to a mismatch in the ventilation-to-perfusion ratio because alveolar ventilation remains the same. Still, pulmonary capillary blood flow decreases, leading to dead space ventilation and hypoxemia. Also, mediators, eg, serotonin, are released, which cause vasospasm and further decrease pulmonary flow in unaffected lung areas. Local accumulation of inflammatory mediators alters lung surfactant and stimulates respiratory drive, resulting in hypocapnia and respiratory alkalosis.[16]

In PE, pulmonary vascular resistance increases due to the mechanical obstruction of the vascular bed with thrombus and hypoxic vasoconstriction. Pulmonary artery pressure increases if thromboembolic occlusion is >30% to 50% of the total cross-sectional area of the pulmonary arterial bed. Increased pulmonary vascular resistance increases the right ventricular afterload, which impedes right ventricular outflow and causes right ventricular dilation and flattening or bowing of the interventricular septum. Developing the right bundle branch block may increase the desynchronization of the ventricles. The decreased right ventricular outflow and concomitant right ventricular dilation reduce left ventricular filling, compromising cardiac output.[17]

As a result, left ventricular filling is reduced in early diastole, reducing cardiac output and causing systemic hypotension and hemodynamic instability. Right ventricle failure due to acute pressure overload is the primary cause of death in severe PE. Given the above pathophysiological considerations, clinical symptoms and signs of overt right ventricular failure and hemodynamic instability indicate a high risk of early (in-hospital or 30-day) mortality.

Additionally, the early literature suggested that patients with underlying cardiac disease were at the greatest risk for developing a pulmonary infarction associated with acute PE, as poor collateral circulation, in combination with pulmonary thromboembolism, was thought to result in infarction.[18] However, recent studies suggest the opposite. Specifically, younger patients without cardiopulmonary disease were found to be more likely to suffer a pulmonary infarction secondary to PE.

Experts hypothesize that longstanding local tissue hypoxia from chronic cardiopulmonary disease states leads to more robust bronchial vascular collateralization, protecting parenchyma from infarction.[7] The lung parenchyma receives its oxygen supply from 3 nonredundant sources: deoxygenated blood from pulmonary arteries, oxygenated blood from the bronchial circulation, and direct oxygen diffusion from alveoli.[19] A sufficient impedance from one of these sources can cause infarction and subsequent tissue necrosis. Inflammatory mediators from ischemic parenchyma can further limit gas exchange following the resultant vasoconstriction and bronchoconstriction.[20] When ischemia of lung tissue is not reversed promptly, infarction ensues. A unilateral infarct occurs in 77% to 87% of pulmonary infarctions, with the strongest predilection for the right lower lobe. Multiple studies show a stark predominance of pulmonary infarction in the lower lobes relative to the upper lobes, thought to be due to gravity’s influence on the unique relationship between alveolar, pulmonary, and bronchial arterial pressure.[7][21]

History and Physical

Clinical History

A timely diagnosis of PE is crucial because of the high associated mortality and morbidity, which may be prevented with early treatment. Notably, 30% of untreated patients with PEs die, while only 8% die after timely therapy.[22][23] Unfortunately, diagnosing PE can be difficult due to the variety of nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms in patients with acute PE. The most common symptoms of PE include dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, cough, hemoptysis, presyncope, and syncope. Dyspnea may be acute and severe in a central PE, whereas mild and transient dyspnea is observed in small peripheral PE. In patients with preexisting heart failure or pulmonary disease, worsening dyspnea may be the only symptom. Chest pain is a frequent symptom usually caused by pleural irritation due to distal emboli causing pulmonary infarction.[24] In central PE, chest pain may be from underlying right ventricular ischemia and needs to be differentiated from an acute coronary syndrome or aortic dissection.

Less common presentations include arrhythmias (eg, atrial fibrillation), syncope, and hemodynamic collapse.[25] Hemodynamic instability is a rare but essential form of clinical presentation, as it indicates central or extensive PE with severely reduced hemodynamic reserve. Syncope may occur and may be associated with a higher prevalence of hemodynamic instability and right ventricular dysfunction.[26] Recognizing that patients with large PE may sometimes be asymptomatic or have mild symptoms is crucial. PE may often be asymptomatic or discovered incidentally during diagnostic workup for another disease. Therefore, in addition to PE symptoms, clinicians should look for VTE risk factors to determine the clinical probability of PE.

Physical Examination Findings

On examination, patients with PE might have tachypnea and tachycardia, which are common but nonspecific findings. Other examination findings include calf swelling, tenderness, erythema, palpable cords, pedal edema, rales, decreased breath sounds, signs of pulmonary hypertension, eg, elevated neck veins, a loud P2 component of the second heart sound, a right-sided gallop, and a right ventricular parasternal lift.

PE is a well-recognized cause of sudden cardiac arrest (8%).[27] A massive PE leads to an acute right ventricular failure, which presents as jugular venous distension, parasternal lift, third heart sound, cyanosis, and shock. In a patient with PE who has tachycardia on presentation and develops sudden bradycardia or a new broad complex tachycardia (with right bundle branch block), clinicians should consider the right ventricular strain and impending shock. PE should be suspected in anyone with hypotension with jugular venous distension when acute myocardial infarction, pericardial tamponade, or tension pneumothorax has been ruled out.[28]

Evaluation

Diagnostic Evaluation of Acute Pulmonary Embolus

The diagnosis of an acute PE comprises various laboratory and imaging studies in conjunction with clinical probability scoring systems, such as the Wells and Geneva criteria.

Arterial blood gas analysis

Unexplained hypoxemia with a normal chest radiograph should raise clinical suspicion for PE. Widened alveolar-arterial gradient for oxygen, respiratory alkalosis, and hypocapnia are common findings on arterial blood gas (ABG) as a pathophysiological response to PE. Notably, respiratory or lactic acidosis is uncommon but can be present in patients with massive PE associated with obstructive shock and respiratory arrest.[29]

Brain natriuretic peptide

Elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) has limited diagnostic importance in patients suspected of having PE.[30] Right ventricular pressure overload because of acute PE is associated with more myocardial stretch, releasing BNP and N-terminal-proBNP. Thus, the levels of natriuretic peptides in blood reflect the severity of right ventricular dysfunction in acute PE.[31]

Troponin

Serum troponin I is beneficial prognostically but not diagnostically.[32][33] As a marker of right ventricular dysfunction, troponin levels are elevated in 30% to 50% of patients with moderate to large PE and are linked to clinical deterioration and death after PE.[34]

D-dimer

D-dimer levels are elevated in plasma whenever an acute thrombotic process occurs in the body because the coagulation and fibrinolysis pathways are activated simultaneously. D-dimer testing has a high negative predictive value; hence, a normal D-dimer level makes acute PE or DVT unlikely.[35] However, since the positive predictive value of elevated D-dimer levels is low, D-dimer testing is not used to confirm PE.

As many D-dimer assays are available, clinicians should become aware of the diagnostic performance of the test used in their clinical setting. The quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) has a diagnostic sensitivity of at least 95%. ELISA can exclude the diagnosis of PE in patients with either low or intermediate pretest probability. A negative ELISA D-dimer and low clinical probability can exclude PE in approximately 30% of suspected patients without further testing.

The specificity of D-dimer decreases steadily with age to approximately 10% in patients older than 80. Using age-adjusted cut-offs for patients older than 50 may improve the performance of D-dimer testing in older adults. In one study, using the age-adjusted cut-off instead of the standard D-dimer cut-off of 500 ng/mL or more increased the number of patients in whom the possibility of PE could be ruled out from 6.4% to 30%, without additional false-negative findings.[36] The formula is age (years) x 10 ng/mL for patients older than 50. For example, patient age 75 = age-adjusted d-dimer of 750 ng/mL.

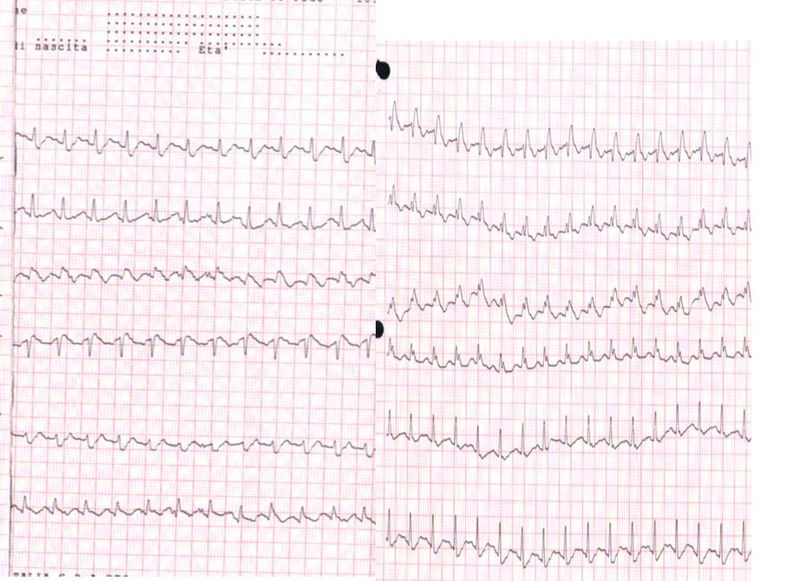

Electrocardiography

Electrocardiography (ECG) abnormalities in patients with suspected PE are nonspecific.[37] The most common ECG findings in PE are tachycardia and nonspecific ST-segment, T-wave changes, S1Q3T3 pattern, right ventricular strain, and new incomplete right bundle branch block, which are uncommon (see Image. Electrocardiogram, Pulmonary Embolism).

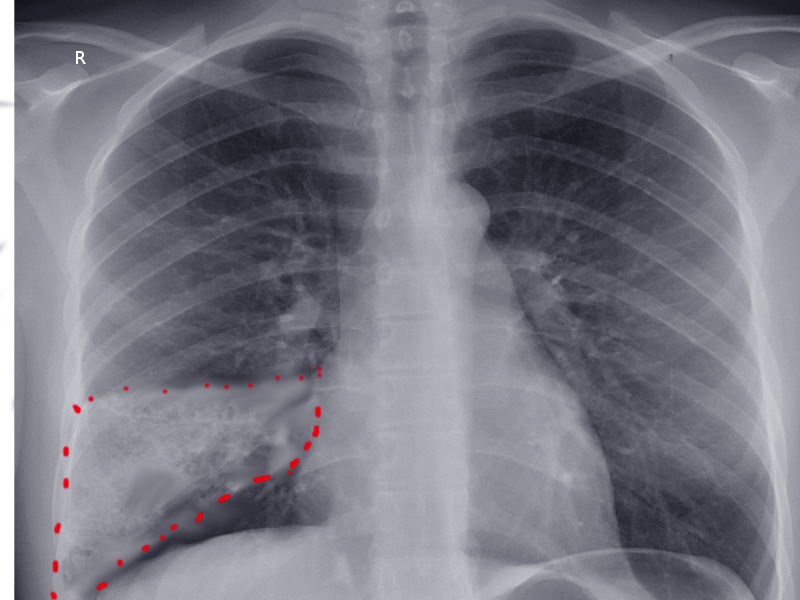

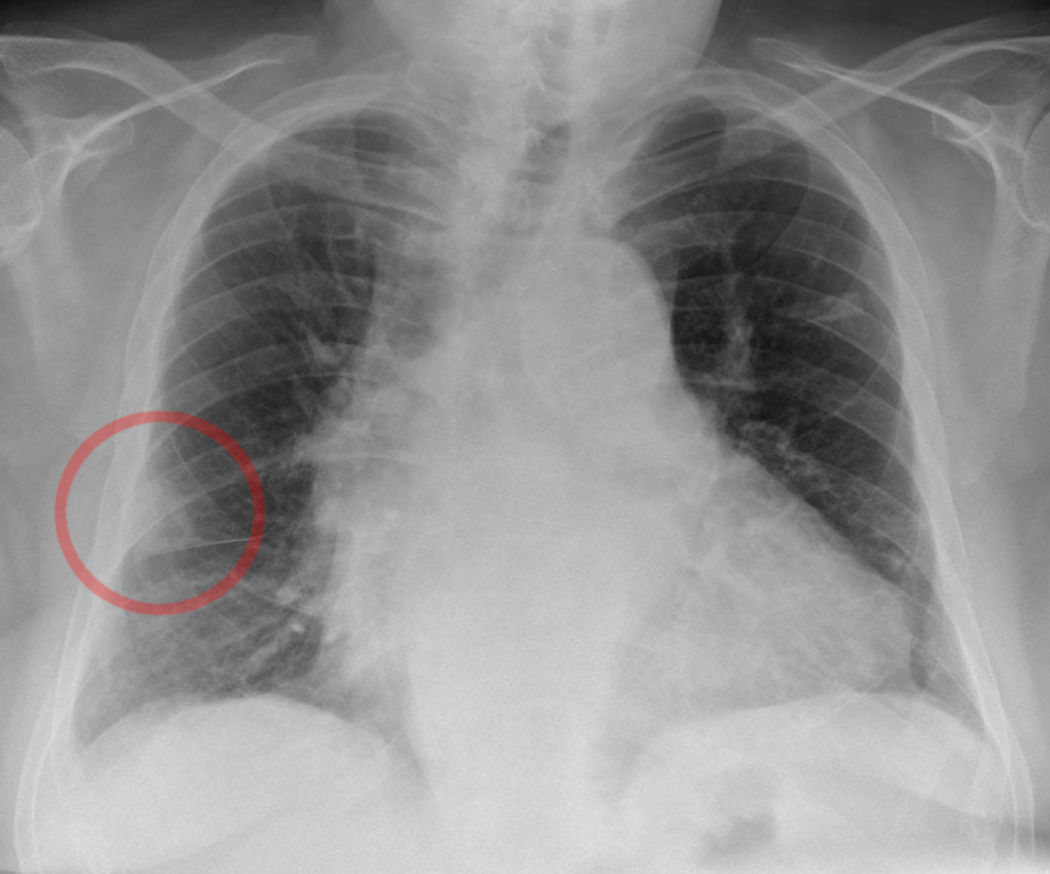

Chest radiograph

In PE, a chest radiograph (CXR) is usually normal or might show nonspecific abnormalities such as atelectasis or effusion. It helps to rule out alternative diagnoses in patients presenting with acute dyspnea. CXR image may be the first clue toward diagnosing pulmonary infarction (see Image. Wedge-Shaped Pulmonary Infarction). A "Hampton hump" (wedge-shaped consolidation at the lung periphery), Westermark sign (radiographic oligemia or increased lucency), and Fleischer sign (prominent pulmonary artery) are specific findings but lack sensitivity to be diagnostically sufficient. A sensitivity and specificity of 22% and 82%, respectively, with Hampton hump, have been quoted in the literature (see Image. Hampton Hump).[38] Other features, such as atelectasis or focal consolidation, may be present but are neither sensitive nor specific.[39] The Westermark sign is the sharp cut-off of pulmonary vessels with distal hypoperfusion in a segmental distribution within the lung; these findings are rare but specific to acute PE.[39] Westermark sign may be seen in up to 2% of the cases, resulting from a combination of dilation of the pulmonary artery proximal to the thrombus and the collapse of the distal vasculature.

Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA)

Multidetector computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is the diagnostic modality of choice for patients with suspected PE. CTPA allows appropriate visualization of the pulmonary arteries down to the subsegmental level.[40] The PIOPED (Prospective Investigation On Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis) II study showed a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 96% for CTPA in PE diagnosis.[41] Moreover, CTPA is the most commonly used imaging technique to diagnose pulmonary infarction in combination with appropriate clinical context (see Image. Pulmonary Embolism). CT findings associated with pulmonary infarction include a feeding vessel or "vessel sign," central lucency, and a semicircular shape. The finding of air bronchograms made a pulmonary infarction less likely.[7] If a vessel sign with a central lucency and no air bronchogram is present on CT, the specificity for detecting pulmonary infarction is 99%.[42]

PIOPED II also highlighted the influence of pretest clinical probability on the predictive value of CTPA. A normal CTPA had a high negative predictive value for PE at 96% and 89% in patients with a low or intermediate clinical probability, respectively, but its negative predictive value was only 60% if the pretest probability was high. Contrarily, the positive predictive value of a positive CTPA was high (92% to 96%) in patients with an intermediate or high clinical probability but much lower (58%) in patients with a low pretest likelihood of PE.[41] Therefore, clinicians should consider further testing in case of discordance between clinical judgment and the CTPA result. The present data suggest that a negative CTPA result is adequate for excluding PE in patients with a low or intermediate clinical probability. Whether patients with a negative CTPA and a high clinical probability should be further investigated remains controversial.

CTPA may be relatively contraindicated in moderate to severe iodinated contrast allergy or renal insufficiency (eGFR <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2). The risk of these contraindications must be measured against the clinical significance of performing the CTPA examination and the availability of other imaging modalities, eg, ventilation/perfusion scan (V/Q scan). If clinically feasible, CTPA should be postponed for premedication for a history of allergy or IV hydration for renal insufficiency.

CTPA can detect right ventricular enlargement and other indicators of right ventricular dysfunction. Enlarged right ventricular has predictive value, supported by the results of a prospective multicentre cohort study in 457 patients.[43] In that study, right ventricular enlargement (right ventricular/left ventricular ratio ≥0.9) was a strong and independent predictor of a severe in-hospital outcome in the overall population and hemodynamically stable patients.

Lung scintigraphy

The planar V/Q scan is an established diagnostic test for suspected PE, mainly performed for patients in whom CTPA is contraindicated or inconclusive or when additional testing is needed. A normal chest radiograph is usually required before V/Q scanning. Scans performed on patients with abnormal chest radiographs are likely false positives because the images do not appear normal or a low probability of PE in such patients is present.

V/Q scanning remains the test of choice for diagnosing PE in pregnancy for those with a normal chest radiograph. Other patients include those with a history of contrast medium-induced anaphylaxis and those with severe renal failure.[44] Planar lung scan results are frequently classified into 3 tiers: normal scan (excluding PE), high-probability scan (considered diagnostic of PE in most patients), and nondiagnostic scan.[44][45] Multiple studies have suggested that it is safe to withhold anticoagulant therapy in patients with a normal perfusion scan.[46]

An analysis from the PIOPED II study advocated that a high-probability V/Q scan can confirm PE. However, the positive predictive value of a high-probability V/Q scan is not enough to confirm the PE diagnosis in patients with a low clinical probability.[47] The high frequency of nondiagnostic scans is a limitation because they require further diagnostic testing.

Pulmonary angiography

In pulmonary angiography, contrast is injected via a catheter introduced into the right heart under fluoroscopy, which was the gold standard in the past for diagnosing PE. The diagnosis of acute PE is made on the evidence of a thrombus, either as amputation of a pulmonary arterial branch or a filling defect.[48]

With the widespread emergence of CTPA, pulmonary angiography is infrequently used and reserved for rare circumstances for patients with a high clinical probability of PE, in whom CTPA or V/Q scanning is nondiagnostic. Pulmonary angiography seems inferior to CTPA; the results are operator-dependent and highly variable.[49] Therefore, catheter-based pulmonary angiography is performed in patients who need therapeutic benefit since it helps with diagnosis and therapeutic interventions aimed at clot lysis.

Magnetic resonance angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) regarding suspected PE has been assessed for several years. However, large-scale studies show that this promising technique is not recommended as a first-line test for diagnosing PE due to its low sensitivity, low availability in most emergency settings, and the high proportion of inconclusive MRA scans.[50] However, clinicians may consider this imaging option to evaluate PE in patients in whom neither CTPA nor V/Q scan can be performed.

Potential advantages include no exposure to radiation. MR pulmonary angiography was studied prospectively in 371 adults with suspected PE. Among the 75% of patients with technically adequate images, MRPA alone showed a sensitivity and specificity of 78% and 99%, respectively.[50] Among the 48% of patients with technically adequate images, MR pulmonary angiography and MR pulmonary venography have shown a sensitivity and specificity of 92% and 96%, respectively.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography can rarely definitively diagnose PE when the thrombus is visualized in the proximal pulmonary arteries. The diagnosis of PE on echocardiography is supported by the presence of a clot in the right heart or new right heart strain, especially in hemodynamically unstable patients with suspected PE. An echocardiogram may be helpful to establish a possible diagnosis and justify the emergency use of thrombolytic therapy (see Image. Transesophageal Echocardiography, Pulmonary Embolism).

Significant considerations are apparent when using echocardiography to establish a diagnosis of PE. Given the right ventricular's peculiar shape, no single echocardiographic parameter gives quick and accurate right ventricular size or function information. That is why echocardiographic criteria for diagnosing PE have varied between different studies. Because of the negative predictive value of 40% to 50%, a negative result cannot exclude PE.[51][52] On the other hand, signs of right ventricular overload or dysfunction may also be present without acute PE and may be due to coexisting cardiac or respiratory disease.[53]

Right ventricular dilation is seen in ≥25% of patients with PE on echo and is helpful for risk stratification of the disease.[54] More specific echocardiography findings confer a high positive predictive value for PE with preexisting cardiorespiratory illness. This includes the combination of a pulmonary ejection acceleration time (measured in the right ventricular outflow tract) <60 milliseconds with a peak systolic tricuspid valve gradient less than 60 mm Hg ('60/60' sign) or McConnell sign (with depressed contractility of the right ventricular free wall compared to the right ventricular apex), is suggestive of PE.[55] A right ventricular/left ventricular diameter ratio of ≥1 and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) <16 mm are the findings for which an association with unfavorable prognosis has most frequently been reported.[56]

Compression ultrasonography

PE originates from a lower-limb DVT in most patients and only rarely from upper-limb DVT (mostly following venous catheterization). One study found DVT in 70% of patients with proven PE.[57] Compression ultrasound has a >90% sensitivity and a specificity of about 95% for proximal symptomatic DVT.[58] A finding of proximal DVT in patients suspected of having PE is considered sufficient to warrant anticoagulant treatment without further testing.[59] Notably, due to the low sensitivity of compression ultrasonography, it is reserved for patients for whom definitive imaging (eg, CTPA, V/Q scanning) is contraindicated or indeterminate.[60]

Acute Pulmonary Embolus Diagnostic Criteria

Wells criteria and Geneva score are scoring systems most commonly used to estimate the pretest probability of having a PE. These systems allow patients with suspected PE to be classified into clinical or pretest probability categories based on which diagnostic tests are chosen and interpreted.

Revised Geneva clinical prediction rule

The following clinical decision rule points are used in the Geneva scoring system (original version)/(simplified version):

- Previous PE or DVT: 3/1

- Heart rate

- 75 to 94 bpm: 3/1

- ≥95 bpm: 5/2

- Surgery or fracture within the past month: 2/1

- Hemoptysis: 2/1

- Active cancer: 2/1

- Unilateral lower-limb pain: 3/1

- Pain on lower-limb deep palpation and unilateral edema: 4/1

- Age >65 years: 1/1

Using the Geneva criteria, the clinical probability of PE in a patient can be calculated using the following 3- or 2-level scoring systems:

- Three-level score

- Low: 0 to 3/0 to 1

- Intermediate: 4 to 10/2 to 4

- High: ≥11/≥5

- Two-level score

- PE unlikely: 0 to 5/0 to 2

- PE likely: ≥6/≥3

Wells criteria and modified Wells criteria

The Wells scoring system uses the following criteria:

- Clinical symptoms of DVT: 3

- Other diagnoses less likely than pulmonary embolism: 3

- Heart rate >100 bpm: 1.5

- Immobilization for ≥3 days or surgery in the previous 4 weeks: 1.5

- Previous history of DVT or PE: 1.5

- Hemoptysis: 1

- Malignancy: 1 [61]

Using the traditional or modified Wells criteria, the clinical probability of PE in a patient can be calculated using the following scores:

- Traditional Wells criteria

- High: >6

- Moderate: 2 to 6

- Low: <2

- Modified Wells criteria

- PE likely: >4

- PE unlikely: ≤4

Pulmonary Embolism Exclusion Criteria

Since PE symptoms are very nonspecific, the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC) was developed for emergency department patients to select patients with a low likelihood of having PE that diagnostic workup should not be initiated.[62] They constitute variables significantly associated with the absence of PE. The PERC rule contains the following 8 criteria:

- Age <50 years

- Heart rate <100 bpm

- Oxyhemoglobin saturation ≥95%

- No hemoptysis

- No estrogen use

- No prior DVT or PE

- No unilateral leg swelling

- No surgery/trauma requiring hospitalization within the preceding 4 weeks

For patients who fulfill all 8 criteria having a low probability of PE, the likelihood of PE is sufficiently low that further testing is not indicated. PERC is only valid in clinical settings with a low prevalence of PE (<15%).[63] In hospital settings with a higher prevalence of PE (>15%), the PERC-based approach has substantially weaker predictive value.[64] Therefore, PERC criteria should not be used in patients with an intermediate or high suspicion of PE or inpatients suspected of having PE.

Pulmonary Embolism Diagnostic Evaluation Approach in Hemodynamically Stable Patients

An approach that combines clinical and pretest probability assessment, D-dimer testing, and definitive diagnostic imaging is usually applied for most hemodynamically stable patients with suspected PE.[51]

Low probability of pulmonary embolus (Wells score <2)

If PERC criteria are fulfilled, further testing is unneeded, and PE can be excluded. If PERC criteria are not met, then a D-dimer should be obtained. If D-dimer is negative, PE can be ruled out (<500 ng/mL). CT pulmonary angiography should be performed if the D-dimer is positive (>500 ng/mL) in patients aged <50 or higher after the age-adjusted D-dimer value. If CTPA is inconclusive or contraindicated, a V/Q scan should be performed. For a patient with an intermediate probability of PE (Wells score 2 to 6), measure D-dimer levels; if negative, PE can be excluded. If positive, then CTPA is done. If CTPA is inconclusive or contraindicated, a V/Q scan should be performed.[51]

High probability of pulmonary embolus (Wells score >6)

CTPA should be performed emergently in patients with a high likelihood of PE. Feasibility requires adequate scanner technology, and the patient must be able to lie flat, cooperate with exam breath-holding instructions, have a body habitus that can fit into the scanner, and have no contraindications for iodinated contrast. If the CTPA is inconclusive or not feasible, clinicians should perform a V/Q scan.

A normal V/Q scan excludes PE. A PE may be diagnosed in patients with a V/Q scan demonstrating a high probability of PE. For a V/Q scan resulting in intermediate probability, further testing with lower extremity compression ultrasonography with Doppler is appropriate. For patients who are hemodynamically unstable and in whom definitive imaging is unsafe, bedside echocardiography or venous compression ultrasound may be used to obtain a presumptive diagnosis of PE to justify the administration of potentially life-saving therapies.[51]

Treatment / Management

Initial Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolus

Supportive measures

The initial approach to patients with PE should focus on supportive measures. Supplemental oxygen is indicated in patients with oxygen saturation <90%. Mechanical ventilation (noninvasive or invasive) should be utilized in unstable patients, but clinicians should be mindful of the adverse hemodynamic effects of mechanical ventilation.

Acute right ventricular failure is the leading cause of death in patients with hemodynamically unstable PE. Aggressive volume resuscitation in such patients can over-distend the right ventricular, worsen ventricular interdependence, and reduce cardiac output. Hence, in patients with massive PE, intravenous fluid resuscitation should be tried only in patients with collapsible inferior vena cava (IVC)/intravascular depletion. Vasopressors may be needed for hemodynamic support. Mechanical cardiopulmonary support devices, such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, may be used in hemodynamically unstable patients with PEs.

Anticoagulation

Remembering that anticoagulation is the mainstay of treating acute PE is vital. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH; fondaparinux) or unfractionated heparin (UFH) can be used for anticoagulation in acute PE. LMWH and fondaparinux are preferred since they lower the incidence of inducing major bleeding and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.[65][66] UFH is usually only used in patients with hemodynamic instability in whom primary reperfusion treatment might be required or in patients with renal impairment. Newer oral anticoagulants (NOACs) and vitamin K antagonists (VKA) can also be used for anticoagulation in PE.(A1)

Anticoagulation and hemodynamic stability

The treatment for patients with suspected PE is stratified according to the type of PE (hemodynamically stable or unstable) and the clinician's suspicion index. Based on the revised Geneva or Wells score, patients are classified as having low, intermediate, or high suspicion of PE.

Anticoagulation is started before diagnostic imaging is obtained for hemodynamically stable patients with a high clinical suspicion of PE. For hemodynamically stable patients with a low clinical suspicion for PE, if diagnostic imaging can be performed within 24 hours, clinicians should wait for imaging studies to establish a definitive diagnosis before starting treatment with anticoagulation. For hemodynamically stable patients with an intermediate clinical suspicion of PE, if diagnostic imaging can be performed within 4 hours, clinicians should wait for imaging studies to establish a definitive diagnosis before starting treatment with anticoagulation. For hemodynamically stable patients in whom anticoagulation is contraindicated, IVC filter placement should be considered when the diagnosis of PE is confirmed.

For patients with a high clinical suspicion of PE who are hemodynamically unstable, emergent CTPA, portable perfusion scanning, or bedside transthoracic echocardiography should be performed whenever possible. Primary reperfusion treatment, usually thrombolysis, is the treatment of choice for patients with hemodynamically unstable acute PE. Surgical pulmonary embolectomy or percutaneous catheter-directed therapy are alternative reperfusion options in patients with contraindications to thrombolysis. Following reperfusion treatment and hemodynamic stabilization, patients recovering from high-risk PE can be switched from parenteral to oral anticoagulation.

Reperfusion Strategies

Thrombolysis

Thrombolysis has shown an effective reduction in pulmonary artery pressure and resistance in patients with PE compared to UFH alone; a decrease in right ventricular dilation on echocardiography assesses these improvements.[67][68] Thrombolysis is preferred when therapy can be instituted within 48 hours of symptom onset, but it has still shown benefit in patients whose symptoms began less than 14 days ago.[69] A meta-analysis suggested a significant reduction in mortality and recurrent PE using thrombolytics.[70](A1)

Pulmonary Embolism Thrombolysis (PEITHO) trial identified the benefits of thrombolysis in hemodynamically stable patients with intermediate-risk PE.[71] It demonstrated that thrombolysis was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of hemodynamic decompensation or collapse, but it also showed an increased risk of severe bleeding with thrombolytics.[71][72](A1)

Absolute contraindications to thrombolysis include any prior intracranial hemorrhage, known structural intracranial cerebrovascular disease (eg, arteriovenous malformation), known malignant intracranial neoplasm, ischemic stroke within 3 months, suspected aortic dissection, active bleeding or bleeding diathesis, recent surgery encroaching on the spinal canal or brain, and recent significant closed-head or facial trauma with radiographic evidence of bony fracture or brain injury.

Catheter-directed treatment

Catheter-directed treatment involves the insertion of a catheter into the pulmonary arteries, which is then used for ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis, suction embolectomy, rotational embolectomy, thrombus aspiration, or combining mechanical fragmentation with pharmacological catheter-directed thrombolysis. Different studies have shown a success rate of up to 87% for catheter-directed therapies.[73][74] Catheter-assisted embolectomy techniques carry the inherent risk of perforating the pulmonary arteries, leading to massive hemoptysis or cardiac tamponade. These complications are rare but fatal.(A1)

Surgical embolectomy

Surgical embolectomy is usually indicated in a patient with hemodynamically unstable PE in whom thrombolysis (systemic or catheter-directed) is contraindicated or in patients with failed thrombolysis.[75][76][77] For thrombolysis or surgical embolectomy, no difference in mortality is evident, but the thrombolysis group had a higher risk of stroke and repeated intervention.

Vena cava filters

Vena cava filters block the path of travel of emboli and prevent them from entering the pulmonary circulation. Filters are indicated in patients with venous thromboembolism who have an absolute contraindication to anticoagulants and in patients with recurrent VTE despite anticoagulation. Retrievable filters are preferred, such that after the contraindication has resolved, the filter can be removed, and patients should be anticoagulated. This is because the Prevention of Recurrent Pulmonary Embolism by Vena Cava Interruption (PREPIC) study showed that the insertion of a permanent vena cava filter was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of recurrent PE and a substantial increase in the risk of DVT, without a remarkable difference in the risk of recurrent VTE or death.[78](A1)

Long-Term Treatment and Prevention of Recurrence

The aim of anticoagulation after the acute management of PE is to complete the treatment of the acute episode and prevent the recurrence of VTE over the long term. Clinical trials have assessed various durations of anticoagulant therapy with VKAs for VTE.[79][80][81] The findings of these studies established a treatment protocol for acute PE.(A1)

First, all patients with PE should receive 3 months or more of anticoagulant treatment. Second, after the anticoagulant treatment is stopped, the risk of recurrence is expected to be similar if anticoagulants are stopped after 3 to 6 months compared with more prolonged treatment periods (eg, 12 to 24 months). Third, extended oral anticoagulant treatment reduces the risk of recurrent VTE by ≤90%, but the risk of bleeding partially offsets this benefit. Oral anticoagulants are highly efficient in preventing recurrent VTE at the time of treatment, but after the discontinuation of treatment, they do not eliminate the risk of subsequent recurrence.[79](A1)

Notably, about 30% of PEs are unprovoked. Unprovoked PE (ie, PE in the absence of an identifiable risk factor) is associated with a 2- to 3-fold increase in the risk of recurrence compared to patients who had a provoked PE.[82] Patients with persistent risk factors (eg, cancer or elevated antiphospholipid antibodies) have a higher rate of recurrence than those with transient risk factors (eg, immobilization, surgery, or trauma).[83](A1)

Consequently, the optimal duration of anticoagulation remains uncertain and should be individualized. A minimum of 3 months is usually recommended, but a more extended period is required if the PE was unprovoked or persistent risk factors are evident.[82] This need for longer anticoagulation should be assessed at the end of 3 months by considering the patient's bleeding risk. Those with a high bleeding risk can limit therapy to 3 months. Special considerations are required for patients with active cancer, given their increased risk for a VTE event. Hence, cancer patients should receive an extended duration of anticoagulation if their bleeding risk remains acceptable (low or moderate bleeding risk). For cancer patients with PE, LMWH, and direct oral anticoagulants (eg, apixaban and rivaroxaban) are preferred over VKA.[84](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Since PE has a very heterogeneous clinical presentation ranging from dyspnea to sudden cardiac arrest.[85] The differential diagnosis of PE is extensive and includes:

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Stable angina

- Acute pericarditis

- Congestive heart failure

- Malignancy

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Pneumonia

- Pneumonitis

- Pneumothorax

- Vasovagal syncope

Prognosis

Shock and right ventricular dysfunction confer a poor prognosis and predict mortality in patients diagnosed with PE.[63] Patients with PE and a coexisting DVT are also at an increased risk for death. While earlier reports reported a high rate of mortality following pulmonary infarction, a study from 2018 found the survival to discharge rate of those suffering from a pulmonary infarction to be high at around 97%.[86]

Several prognostic models have been designed, but the PE Severity Index (PESI) and the simplified PESI (sPESI) are the most commonly used. The PESI score predicts 30-day mortality in patients with an established diagnosis of PE.[87] The principal strength of the PESI and sPESI is identifying patients at low risk for 30-day mortality (PESI classes I and II).

Original and Simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index

The following parameters are utilized in each version of the PESI (original version [87]/simplified version [88]):

- Age: 1 point (if age older than 80 years)

- Male sex: +10 points/–

- Cancer: +30 points/1 point

- Chronic heart failure: +10 points/1 point

- Chronic pulmonary disease: +10 points/1 point

- Pulse rate ≥110 bpm: +20 points/1 point

- Systolic BP <100 mm Hg: +30 points/1 point

- Respiratory rate >30 breaths/min: +20 points/–

- Temperature <36 °C: +20 points/–

- Altered mental status: +60 points/–

- Arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation <90%: +20 points/1 point

Risk Stratification in PESI includes the following classes:

- Class I: Points ≤65; low 30-day mortality risk from 1% to 6%.

- Class II: Points 66 to 85; low mortality risk from 1.7% to 3.5%

- Class III: Points 86 to 105; moderate mortality risk from 3.2% to 7.1%

- Class IV: Points 106 to 125; high mortality risk from 4% to 11.4%

- Class V: Points >125; high mortality risk from 10% to 24.5%

Risk Stratification in sPESI includes the following classes:

- If 0 points: 1.0% 30-day mortality risk

- If ≥1 points: 10.9% 30-day mortality risk

Complications

The primary complications associated with PE include:

- Recurrent thromboembolism

- Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

- Right heart failure

- Cardiogenic shock

PE, if left untreated, is associated with mortality of up to 30%. Studies have also suggested an increased risk of stroke, thought to be due to paradoxical embolism via a patent foramen ovale in patients with acute PE.[89]

Recurrent Thromboembolism

In the 1 to 2 weeks following diagnosis, patients may deteriorate and experience recurrence. Inadequate anticoagulation is the most common reason for recurrent venous thromboembolism while on therapy.

Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension

The development of persistent or progressive dyspnea, particularly during the first 3 months to 2 years after diagnosis, should prompt the clinician to investigate the development of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), which affects up to 5% of patients. In patients who remain persistently symptomatic months to years after an acute PE, follow-up CT, ventilation-perfusion scans, or echocardiography should be performed. These modalities demonstrate pulmonary hypertension in CTEPH.

On the V/Q scan, patients with CTEPH generally have at least 1 segmental or more significant mismatched ventilation-perfusion defect. For those patients with evidence of CTEPH on V/Q lung scanning, right heart catheterization, and pulmonary angiography are indicated to confirm pulmonary hypertension, quantify the degree of pulmonary hypertension, exclude competing diagnoses, define the surgical accessibility of the obstructing thrombotic lesions, and confirm that an acceptable component of the elevated pulmonary vascular resistance is due to surgically accessible disease and not from distal obstruction or a secondary arteriopathy, for all patients with CTEPH, lifelong anticoagulant therapy is recommended. Also, early referral for evaluation for pulmonary thromboendarterectomy is highly recommended.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Individuals who have survived PEs often demonstrate decreases in multiple functional deficits, including respiratory volume, exercise tolerance, and reported quality of life. Approximately half of the survivors have persistent symptoms reducing their physical capacity. Continuing studies are needed to identify risk factors for individuals more likely to experience significant deficits following PE resolution.

The results of various studies have demonstrated different parameters for rehabilitation following PE and various program initiation times, ranging from weeks to months following diagnosis. These studies demonstrate minimal risks, with outcomes including a significant reduction in dyspnea and improvement in exercise capacity, functional mobility, and quality of life.[90][91] Rehabilitation services should work closely with the other care team members to identify deficits and develop a tailored care plan to address these deficits within safe parameters for each patient.

Pearls and Other Issues

A timely diagnosis of PE is crucial because of the high associated mortality and morbidity, which may be prevented with early treatment. Patients should be aware of the signs and symptoms of VTE and PE since the incidence of recurrent thromboembolism is high. Notably, 30% of untreated patients with PEs die, while only 8% die after timely therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of acute PE requires seamless interprofessional collaboration to enhance patient-centered care, improve outcomes, and ensure patient safety. Pulmonary embolism response teams (PERTs) have emerged as an innovative approach to addressing the complexities of PE treatment. Composed of specialists in pulmonary medicine, critical care, cardiology, and cardiothoracic surgery, PERTs facilitate prompt diagnosis and timely intervention, ensuring that patients benefit from the collective expertise of diverse disciplines. Studies demonstrate that PERTs improve communication, streamline treatment efforts, and lead to more coordinated and effective care.

In the larger framework of an interprofessional team, nurses, pharmacists, and advanced practitioners play pivotal roles alongside physicians. As frontline clinicians, nurses contribute critical observations and ensure the timely implementation of prophylactic or therapeutic interventions. Pharmacists, as experts in anticoagulation therapy, provide essential input on drug selection, contraindications, and potential interactions, ensuring the safety and efficacy of treatment. Open communication and mutual respect among all healthcare professionals allow for comprehensive and well-informed decision-making, empowering each team member to contribute actively to patient care.

By fostering a collaborative environment, PERTs and interprofessional teams optimize care coordination and team performance. This approach emphasizes shared responsibilities, effective communication, and a unified strategy, leading to enhanced patient outcomes and improved safety in managing acute PE. Integrating diverse expertise within a cohesive team ensures patients receive timely, evidence-based, patient-centered care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Electrocardiogram, Pulmonary Embolism. The ECG of a patient with pulmonary embolism showed sinus tachycardia of approximately 150 bpm and a right bundle branch block.

Walter Serra, Giuseppe De Iaco, Claudio Reverberi, Tiziano Gherli, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Video to Play)

Transesophageal Echocardiography, Pulmonary Embolism. Acute ECG segment elevation mimicking myocardial infarction in a patient with pulmonary embolism.

T Goslar, M Podbregar, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Hampton Hump. A shallow, hump-shaped opacity on CXR in the periphery of the lung is characteristic of Hampton Hump, indicating pulmonary embolism.

Hellerhof, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

COON WW, WILLIS PW. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: prediction, prevention and treatment. The American journal of cardiology. 1959 Nov:4():611-21 [PubMed PMID: 13811755]

Goldhaber SZ, Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of risk factors for pulmonary embolism in women. JAMA. 1997 Feb 26:277(8):642-5 [PubMed PMID: 9039882]

Gohil R, Peck G, Sharma P. The genetics of venous thromboembolism. A meta-analysis involving approximately 120,000 cases and 180,000 controls. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2009 Aug:102(2):360-70. doi: 10.1160/TH09-01-0013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19652888]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRogers MA, Levine DA, Blumberg N, Flanders SA, Chopra V, Langa KM. Triggers of hospitalization for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2012 May 1:125(17):2092-9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.084467. Epub 2012 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 22474264]

Anderson FA Jr, Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003 Jun 17:107(23 Suppl 1):I9-16 [PubMed PMID: 12814980]

Kaptein FHJ, Kroft LJM, Hammerschlag G, Ninaber MK, Bauer MP, Huisman MV, Klok FA. Pulmonary infarction in acute pulmonary embolism. Thrombosis research. 2021 Jun:202():162-169. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.03.022. Epub 2021 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 33862471]

Islam M, Filopei J, Frank M, Ramesh N, Verzosa S, Ehrlich M, Bondarsky E, Miller A, Steiger D. Pulmonary infarction secondary to pulmonary embolism: An evolving paradigm. Respirology (Carlton, Vic.). 2018 Mar 25:():. doi: 10.1111/resp.13299. Epub 2018 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 29577524]

Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA. 2005 Feb 9:293(6):715-22 [PubMed PMID: 15701913]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceClayton TC, Gaskin M, Meade TW. Recent respiratory infection and risk of venous thromboembolism: case-control study through a general practice database. International journal of epidemiology. 2011 Jun:40(3):819-27. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr012. Epub 2011 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 21324940]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePrandoni P, Pesavento R, Sørensen HT, Gennaro N, Dalla Valle F, Minotto I, Perina F, Pengo V, Pagnan A. Prevalence of heart diseases in patients with pulmonary embolism with and without peripheral venous thrombosis: findings from a cross-sectional survey. European journal of internal medicine. 2009 Sep:20(5):470-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.06.001. Epub 2009 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 19712846]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSørensen HT, Horvath-Puho E, Pedersen L, Baron JA, Prandoni P. Venous thromboembolism and subsequent hospitalisation due to acute arterial cardiovascular events: a 20-year cohort study. Lancet (London, England). 2007 Nov 24:370(9601):1773-9 [PubMed PMID: 18037081]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWendelboe AM, Raskob GE. Global Burden of Thrombosis: Epidemiologic Aspects. Circulation research. 2016 Apr 29:118(9):1340-7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306841. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27126645]

Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, Buller H, Gallus A, Hunt BJ, Hylek EM, Kakkar A, Konstantinides SV, McCumber M, Ozaki Y, Wendelboe A, Weitz JI, ISTH Steering Committee for World Thrombosis Day. Thrombosis: a major contributor to global disease burden. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2014 Nov:34(11):2363-71. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304488. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25304324]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHorlander KT, Mannino DM, Leeper KV. Pulmonary embolism mortality in the United States, 1979-1998: an analysis using multiple-cause mortality data. Archives of internal medicine. 2003 Jul 28:163(14):1711-7 [PubMed PMID: 12885687]

Moser KM. Venous thromboembolism. The American review of respiratory disease. 1990 Jan:141(1):235-49 [PubMed PMID: 2404439]

Nakos G, Kitsiouli EI, Lekka ME. Bronchoalveolar lavage alterations in pulmonary embolism. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1998 Nov:158(5 Pt 1):1504-10 [PubMed PMID: 9817700]

Morrone D, Morrone V. Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Focus on the Clinical Picture. Korean circulation journal. 2018 May:48(5):365-381. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2017.0314. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29737640]

Miniati M. Pulmonary Infarction: An Often Unrecognized Clinical Entity. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 2016 Nov:42(8):865-869 [PubMed PMID: 27743556]

Tsao MS, Schraufnagel D, Wang NS. Pathogenesis of pulmonary infarction. The American journal of medicine. 1982 Apr:72(4):599-606 [PubMed PMID: 6462058]

Kroegel C, Reissig A. Principle mechanisms underlying venous thromboembolism: epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology and pathogenesis. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2003 Jan-Feb:70(1):7-30 [PubMed PMID: 12584387]

Choi SH, Cha SI, Shin KM, Lim JK, Yoo SS, Lee SY, Lee J, Kim CH, Park JY, Lee DH. Clinical Relevance of Pleural Effusion in Patients with Pulmonary Embolism. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2017:93(4):271-278. doi: 10.1159/000457132. Epub 2017 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 28196360]

Carson JL, Kelley MA, Duff A, Weg JG, Fulkerson WJ, Palevsky HI, Schwartz JS, Thompson BT, Popovich J Jr, Hobbins TE. The clinical course of pulmonary embolism. The New England journal of medicine. 1992 May 7:326(19):1240-5 [PubMed PMID: 1560799]

Nijkeuter M, Söhne M, Tick LW, Kamphuisen PW, Kramer MH, Laterveer L, van Houten AA, Kruip MJ, Leebeek FW, Büller HR, Huisman MV, Christopher Study Investigators. The natural course of hemodynamically stable pulmonary embolism: Clinical outcome and risk factors in a large prospective cohort study. Chest. 2007 Feb:131(2):517-23 [PubMed PMID: 17296656]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStein PD, Henry JW. Clinical characteristics of patients with acute pulmonary embolism stratified according to their presenting syndromes. Chest. 1997 Oct:112(4):974-9 [PubMed PMID: 9377961]

Stein PD, Beemath A, Matta F, Weg JG, Yusen RD, Hales CA, Hull RD, Leeper KV Jr, Sostman HD, Tapson VF, Buckley JD, Gottschalk A, Goodman LR, Wakefied TW, Woodard PK. Clinical characteristics of patients with acute pulmonary embolism: data from PIOPED II. The American journal of medicine. 2007 Oct:120(10):871-9 [PubMed PMID: 17904458]

Barco S, Ende-Verhaar YM, Becattini C, Jimenez D, Lankeit M, Huisman MV, Konstantinides SV, Klok FA. Differential impact of syncope on the prognosis of patients with acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European heart journal. 2018 Dec 14:39(47):4186-4195. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy631. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30339253]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCourtney DM, Sasser HC, Pincus CL, Kline JA. Pulseless electrical activity with witnessed arrest as a predictor of sudden death from massive pulmonary embolism in outpatients. Resuscitation. 2001 Jun:49(3):265-72 [PubMed PMID: 11719120]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKucher N, Goldhaber SZ. Management of massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2005 Jul 12:112(2):e28-32 [PubMed PMID: 16009801]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWood KE. Major pulmonary embolism: review of a pathophysiologic approach to the golden hour of hemodynamically significant pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2002 Mar:121(3):877-905 [PubMed PMID: 11888976]

Kiely DG, Kennedy NS, Pirzada O, Batchelor SA, Struthers AD, Lipworth BJ. Elevated levels of natriuretic peptides in patients with pulmonary thromboembolism. Respiratory medicine. 2005 Oct:99(10):1286-91 [PubMed PMID: 16099151]

Henzler T, Roeger S, Meyer M, Schoepf UJ, Nance JW Jr, Haghi D, Kaminski WE, Neumaier M, Schoenberg SO, Fink C. Pulmonary embolism: CT signs and cardiac biomarkers for predicting right ventricular dysfunction. The European respiratory journal. 2012 Apr:39(4):919-26. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00088711. Epub 2011 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 21965223]

Meyer T, Binder L, Hruska N, Luthe H, Buchwald AB. Cardiac troponin I elevation in acute pulmonary embolism is associated with right ventricular dysfunction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000 Nov 1:36(5):1632-6 [PubMed PMID: 11079669]

Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Olschewski M, Kasper W, Hruska N, Jäckle S, Binder L. Importance of cardiac troponins I and T in risk stratification of patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2002 Sep 3:106(10):1263-8 [PubMed PMID: 12208803]

Horlander KT, Leeper KV. Troponin levels as a guide to treatment of pulmonary embolism. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2003 Sep:9(5):374-7 [PubMed PMID: 12904706]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStein PD, Hull RD, Patel KC, Olson RE, Ghali WA, Brant R, Biel RK, Bharadia V, Kalra NK. D-dimer for the exclusion of acute venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Annals of internal medicine. 2004 Apr 20:140(8):589-602 [PubMed PMID: 15096330]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRighini M, Van Es J, Den Exter PL, Roy PM, Verschuren F, Ghuysen A, Rutschmann OT, Sanchez O, Jaffrelot M, Trinh-Duc A, Le Gall C, Moustafa F, Principe A, Van Houten AA, Ten Wolde M, Douma RA, Hazelaar G, Erkens PM, Van Kralingen KW, Grootenboers MJ, Durian MF, Cheung YW, Meyer G, Bounameaux H, Huisman MV, Kamphuisen PW, Le Gal G. Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels to rule out pulmonary embolism: the ADJUST-PE study. JAMA. 2014 Mar 19:311(11):1117-24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2135. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24643601]

Rodger M, Makropoulos D, Turek M, Quevillon J, Raymond F, Rasuli P, Wells PS. Diagnostic value of the electrocardiogram in suspected pulmonary embolism. The American journal of cardiology. 2000 Oct 1:86(7):807-9, A10 [PubMed PMID: 11018210]

Bird SH, Leng RA. Further studies on the effects of the presence or absence of protozoa in the rumen on live-weight gain and wool growth of sheep. The British journal of nutrition. 1984 Nov:52(3):607-11 [PubMed PMID: 6498151]

Worsley DF, Alavi A, Aronchick JM, Chen JT, Greenspan RH, Ravin CE. Chest radiographic findings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: observations from the PIOPED Study. Radiology. 1993 Oct:189(1):133-6 [PubMed PMID: 8372182]

Ghaye B, Szapiro D, Mastora I, Delannoy V, Duhamel A, Remy J, Remy-Jardin M. Peripheral pulmonary arteries: how far in the lung does multi-detector row spiral CT allow analysis? Radiology. 2001 Jun:219(3):629-36 [PubMed PMID: 11376246]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, Gottschalk A, Hales CA, Hull RD, Leeper KV Jr, Popovich J Jr, Quinn DA, Sos TA, Sostman HD, Tapson VF, Wakefield TW, Weg JG, Woodard PK, PIOPED II Investigators. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 Jun 1:354(22):2317-27 [PubMed PMID: 16738268]

Revel MP, Triki R, Chatellier G, Couchon S, Haddad N, Hernigou A, Danel C, Frija G. Is It possible to recognize pulmonary infarction on multisection CT images? Radiology. 2007 Sep:244(3):875-82 [PubMed PMID: 17709834]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBecattini C, Agnelli G, Vedovati MC, Pruszczyk P, Casazza F, Grifoni S, Salvi A, Bianchi M, Douma R, Konstantinides S, Lankeit M, Duranti M. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism: diagnosis and risk stratification in a single test. European heart journal. 2011 Jul:32(13):1657-63. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr108. Epub 2011 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 21504936]

Reid JH, Coche EE, Inoue T, Kim EE, Dondi M, Watanabe N, Mariani G, International Atomic Energy Agency Consultants' Group. Is the lung scan alive and well? Facts and controversies in defining the role of lung scintigraphy for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in the era of MDCT. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2009 Mar:36(3):505-21. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-1014-8. Epub 2009 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 19172269]

Glaser JE, Chamarthy M, Haramati LB, Esses D, Freeman LM. Successful and safe implementation of a trinary interpretation and reporting strategy for V/Q lung scintigraphy. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2011 Oct:52(10):1508-12. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.090753. Epub 2011 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 21803837]

Anderson DR, Kahn SR, Rodger MA, Kovacs MJ, Morris T, Hirsch A, Lang E, Stiell I, Kovacs G, Dreyer J, Dennie C, Cartier Y, Barnes D, Burton E, Pleasance S, Skedgel C, O'Rouke K, Wells PS. Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography vs ventilation-perfusion lung scanning in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007 Dec 19:298(23):2743-53. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.23.2743. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18165667]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSostman HD, Stein PD, Gottschalk A, Matta F, Hull R, Goodman L. Acute pulmonary embolism: sensitivity and specificity of ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy in PIOPED II study. Radiology. 2008 Mar:246(3):941-6. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2463070270. Epub 2008 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 18195380]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePIOPED Investigators. Value of the ventilation/perfusion scan in acute pulmonary embolism. Results of the prospective investigation of pulmonary embolism diagnosis (PIOPED). JAMA. 1990 May 23-30:263(20):2753-9 [PubMed PMID: 2332918]

Wittram C, Waltman AC, Shepard JA, Halpern E, Goodman LR. Discordance between CT and angiography in the PIOPED II study. Radiology. 2007 Sep:244(3):883-9 [PubMed PMID: 17664436]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStein PD, Chenevert TL, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, Gottschalk A, Hales CA, Hull RD, Jablonski KA, Leeper KV Jr, Naidich DP, Sak DJ, Sostman HD, Tapson VF, Weg JG, Woodard PK, PIOPED III (Prospective Investigation of Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis III) Investigators. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography for pulmonary embolism: a multicenter prospective study (PIOPED III). Annals of internal medicine. 2010 Apr 6:152(7):434-43, W142-3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-7-201004060-00008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20368649]

Grifoni S, Olivotto I, Cecchini P, Pieralli F, Camaiti A, Santoro G, Conti A, Agnelli G, Berni G. Short-term clinical outcome of patients with acute pulmonary embolism, normal blood pressure, and echocardiographic right ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2000 Jun 20:101(24):2817-22 [PubMed PMID: 10859287]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTorbicki A, Kurzyna M, Ciurzynski M, Pruszczyk P, Pacho R, Kuch-Wocial A, Szulc M. Proximal pulmonary emboli modify right ventricular ejection pattern. The European respiratory journal. 1999 Mar:13(3):616-21 [PubMed PMID: 10232436]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBova C, Greco F, Misuraca G, Serafini O, Crocco F, Greco A, Noto A. Diagnostic utility of echocardiography in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2003 May:21(3):180-3 [PubMed PMID: 12811708]

Wolfe MW, Lee RT, Feldstein ML, Parker JA, Come PC, Goldhaber SZ. Prognostic significance of right ventricular hypokinesis and perfusion lung scan defects in pulmonary embolism. American heart journal. 1994 May:127(5):1371-5 [PubMed PMID: 8172067]

Kurzyna M, Torbicki A, Pruszczyk P, Burakowska B, Fijałkowska A, Kober J, Oniszh K, Kuca P, Tomkowski W, Burakowski J, Wawrzyńska L. Disturbed right ventricular ejection pattern as a new Doppler echocardiographic sign of acute pulmonary embolism. The American journal of cardiology. 2002 Sep 1:90(5):507-11 [PubMed PMID: 12208411]

Pruszczyk P, Goliszek S, Lichodziejewska B, Kostrubiec M, Ciurzyński M, Kurnicka K, Dzikowska-Diduch O, Palczewski P, Wyzgal A. Prognostic value of echocardiography in normotensive patients with acute pulmonary embolism. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2014 Jun:7(6):553-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.11.004. Epub 2014 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 24412192]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHull RD, Hirsh J, Carter CJ, Jay RM, Dodd PE, Ockelford PA, Coates G, Gill GJ, Turpie AG, Doyle DJ, Buller HR, Raskob GE. Pulmonary angiography, ventilation lung scanning, and venography for clinically suspected pulmonary embolism with abnormal perfusion lung scan. Annals of internal medicine. 1983 Jun:98(6):891-9 [PubMed PMID: 6859705]

Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Hirsh J. The role of venous ultrasonography in the diagnosis of suspected deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Annals of internal medicine. 1998 Dec 15:129(12):1044-9 [PubMed PMID: 9867760]

Le Gal G, Righini M, Sanchez O, Roy PM, Baba-Ahmed M, Perrier A, Bounameaux H. A positive compression ultrasonography of the lower limb veins is highly predictive of pulmonary embolism on computed tomography in suspected patients. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2006 Jun:95(6):963-6 [PubMed PMID: 16732375]

van Rossum AB, van Houwelingen HC, Kieft GJ, Pattynama PM. Prevalence of deep vein thrombosis in suspected and proven pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. The British journal of radiology. 1998 Dec:71(852):1260-5 [PubMed PMID: 10318998]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWells PS, Ginsberg JS, Anderson DR, Kearon C, Gent M, Turpie AG, Bormanis J, Weitz J, Chamberlain M, Bowie D, Barnes D, Hirsh J. Use of a clinical model for safe management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Annals of internal medicine. 1998 Dec 15:129(12):997-1005 [PubMed PMID: 9867786]

Kline JA, Mitchell AM, Kabrhel C, Richman PB, Courtney DM. Clinical criteria to prevent unnecessary diagnostic testing in emergency department patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2004 Aug:2(8):1247-55 [PubMed PMID: 15304025]

Coutance G, Cauderlier E, Ehtisham J, Hamon M, Hamon M. The prognostic value of markers of right ventricular dysfunction in pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Critical care (London, England). 2011:15(2):R103. doi: 10.1186/cc10119. Epub 2011 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 21443777]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHugli O, Righini M, Le Gal G, Roy PM, Sanchez O, Verschuren F, Meyer G, Bounameaux H, Aujesky D. The pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) rule does not safely exclude pulmonary embolism. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2011 Feb:9(2):300-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04147.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21091866]

Stein PD, Hull RD, Matta F, Yaekoub AY, Liang J. Incidence of thrombocytopenia in hospitalized patients with venous thromboembolism. The American journal of medicine. 2009 Oct:122(10):919-30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.03.026. Epub 2009 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 19682670]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCossette B, Pelletier ME, Carrier N, Turgeon M, Leclair C, Charron P, Echenberg D, Fayad T, Farand P. Evaluation of bleeding risk in patients exposed to therapeutic unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin: a cohort study in the context of a quality improvement initiative. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2010 Jun:44(6):994-1002. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M615. Epub 2010 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 20442353]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGoldhaber SZ, Haire WD, Feldstein ML, Miller M, Toltzis R, Smith JL, Taveira da Silva AM, Come PC, Lee RT, Parker JA. Alteplase versus heparin in acute pulmonary embolism: randomised trial assessing right-ventricular function and pulmonary perfusion. Lancet (London, England). 1993 Feb 27:341(8844):507-11 [PubMed PMID: 8094768]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDalla-Volta S, Palla A, Santolicandro A, Giuntini C, Pengo V, Visioli O, Zonzin P, Zanuttini D, Barbaresi F, Agnelli G. PAIMS 2: alteplase combined with heparin versus heparin in the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism. Plasminogen activator Italian multicenter study 2. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1992 Sep:20(3):520-6 [PubMed PMID: 1512328]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDaniels LB, Parker JA, Patel SR, Grodstein F, Goldhaber SZ. Relation of duration of symptoms with response to thrombolytic therapy in pulmonary embolism. The American journal of cardiology. 1997 Jul 15:80(2):184-8 [PubMed PMID: 9230156]

Marti C, John G, Konstantinides S, Combescure C, Sanchez O, Lankeit M, Meyer G, Perrier A. Systemic thrombolytic therapy for acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European heart journal. 2015 Mar 7:36(10):605-14. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu218. Epub 2014 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 24917641]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMeyer G, Vicaut E, Danays T, Agnelli G, Becattini C, Beyer-Westendorf J, Bluhmki E, Bouvaist H, Brenner B, Couturaud F, Dellas C, Empen K, Franca A, Galiè N, Geibel A, Goldhaber SZ, Jimenez D, Kozak M, Kupatt C, Kucher N, Lang IM, Lankeit M, Meneveau N, Pacouret G, Palazzini M, Petris A, Pruszczyk P, Rugolotto M, Salvi A, Schellong S, Sebbane M, Sobkowicz B, Stefanovic BS, Thiele H, Torbicki A, Verschuren F, Konstantinides SV, PEITHO Investigators. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Apr 10:370(15):1402-11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302097. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24716681]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKonstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, Bueno H, Geersing GJ, Harjola VP, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Jennings CS, Jiménez D, Kucher N, Lang IM, Lankeit M, Lorusso R, Mazzolai L, Meneveau N, Áinle FN, Prandoni P, Pruszczyk P, Righini M, Torbicki A, Van Belle E, Zamorano JL, The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). The European respiratory journal. 2019 Sep:54(3):. pii: 1901647. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01647-2019. Epub 2019 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 31473594]

Tafur AJ, Shamoun FE, Patel SI, Tafur D, Donna F, Murad MH. Catheter-Directed Treatment of Pulmonary Embolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Modern Literature. Clinical and applied thrombosis/hemostasis : official journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 2017 Oct:23(7):821-829. doi: 10.1177/1076029616661414. Epub 2016 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 27481877]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBajaj NS, Kalra R, Arora P, Ather S, Guichard JL, Lancaster WJ, Patel N, Raman F, Arora G, Al Solaiman F, Clark DT 3rd, Dell'Italia LJ, Leesar MA, Davies JE, McGiffin DC, Ahmed MI. Catheter-directed treatment for acute pulmonary embolism: Systematic review and single-arm meta-analyses. International journal of cardiology. 2016 Dec 15:225():128-139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.09.036. Epub 2016 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 27718446]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLee T, Itagaki S, Chiang YP, Egorova NN, Adams DH, Chikwe J. Survival and recurrence after acute pulmonary embolism treated with pulmonary embolectomy or thrombolysis in New York State, 1999 to 2013. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2018 Mar:155(3):1084-1090.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.07.074. Epub 2017 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 28942971]

Keeling WB, Sundt T, Leacche M, Okita Y, Binongo J, Lasajanak Y, Aklog L, Lattouf OM, SPEAR Working Group. Outcomes After Surgical Pulmonary Embolectomy for Acute Pulmonary Embolus: A Multi-Institutional Study. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2016 Nov:102(5):1498-1502. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.05.004. Epub 2016 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 27373187]

Pasrija C, Kronfli A, Rouse M, Raithel M, Bittle GJ, Pousatis S, Ghoreishi M, Gammie JS, Griffith BP, Sanchez PG, Kon ZN. Outcomes after surgical pulmonary embolectomy for acute submassive and massive pulmonary embolism: A single-center experience. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2018 Mar:155(3):1095-1106.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.10.139. Epub 2017 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 29452460]

PREPIC Study Group. Eight-year follow-up of patients with permanent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism: the PREPIC (Prevention du Risque d'Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave) randomized study. Circulation. 2005 Jul 19:112(3):416-22 [PubMed PMID: 16009794]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAgnelli G, Prandoni P, Becattini C, Silingardi M, Taliani MR, Miccio M, Imberti D, Poggio R, Ageno W, Pogliani E, Porro F, Zonzin P, Warfarin Optimal Duration Italian Trial Investigators. Extended oral anticoagulant therapy after a first episode of pulmonary embolism. Annals of internal medicine. 2003 Jul 1:139(1):19-25 [PubMed PMID: 12834314]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCampbell IA, Bentley DP, Prescott RJ, Routledge PA, Shetty HG, Williamson IJ. Anticoagulation for three versus six months in patients with deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, or both: randomised trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2007 Mar 31:334(7595):674 [PubMed PMID: 17289685]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchulman S, Rhedin AS, Lindmarker P, Carlsson A, Lärfars G, Nicol P, Loogna E, Svensson E, Ljungberg B, Walter H. A comparison of six weeks with six months of oral anticoagulant therapy after a first episode of venous thromboembolism. Duration of Anticoagulation Trial Study Group. The New England journal of medicine. 1995 Jun 22:332(25):1661-5 [PubMed PMID: 7760866]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoutitie F, Pinede L, Schulman S, Agnelli G, Raskob G, Julian J, Hirsh J, Kearon C. Influence of preceding length of anticoagulant treatment and initial presentation of venous thromboembolism on risk of recurrence after stopping treatment: analysis of individual participants' data from seven trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2011 May 24:342():d3036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3036. Epub 2011 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 21610040]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePoli D, Miniati M. The incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension following a first episode of pulmonary embolism. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2011 Sep:17(5):392-7. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328349289a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21743331]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYoung AM, Marshall A, Thirlwall J, Chapman O, Lokare A, Hill C, Hale D, Dunn JA, Lyman GH, Hutchinson C, MacCallum P, Kakkar A, Hobbs FDR, Petrou S, Dale J, Poole CJ, Maraveyas A, Levine M. Comparison of an Oral Factor Xa Inhibitor With Low Molecular Weight Heparin in Patients With Cancer With Venous Thromboembolism: Results of a Randomized Trial (SELECT-D). Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018 Jul 10:36(20):2017-2023. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8034. Epub 2018 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 29746227]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRezende SM. Barriers in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. The Lancet. Haematology. 2023 Jan:10(1):e11. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00359-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36566044]

Chengsupanimit T, Sundaram B, Lau WB, Keith SW, Kane GC. Clinical characteristics of patients with pulmonary infarction - A retrospective review. Respiratory medicine. 2018 Jun:139():13-18. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.04.008. Epub 2018 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 29857996]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAujesky D, Obrosky DS, Stone RA, Auble TE, Perrier A, Cornuz J, Roy PM, Fine MJ. Derivation and validation of a prognostic model for pulmonary embolism. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005 Oct 15:172(8):1041-6 [PubMed PMID: 16020800]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJiménez D, Aujesky D, Moores L, Gómez V, Lobo JL, Uresandi F, Otero R, Monreal M, Muriel A, Yusen RD, RIETE Investigators. Simplification of the pulmonary embolism severity index for prognostication in patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Archives of internal medicine. 2010 Aug 9:170(15):1383-9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.199. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20696966]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGoliszek S, Wiśniewska M, Kurnicka K, Lichodziejewska B, Ciurzyński M, Kostrubiec M, Gołębiowski M, Babiuch M, Paczynska M, Koć M, Palczewski P, Wyzgał A, Pruszczyk P. Patent foramen ovale increases the risk of acute ischemic stroke in patients with acute pulmonary embolism leading to right ventricular dysfunction. Thrombosis research. 2014 Nov:134(5):1052-6. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.09.013. Epub 2014 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 25282541]

Sista AK, Miller LE, Kahn SR, Kline JA. Persistent right ventricular dysfunction, functional capacity limitation, exercise intolerance, and quality of life impairment following pulmonary embolism: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Vascular medicine (London, England). 2017 Feb:22(1):37-43. doi: 10.1177/1358863X16670250. Epub 2016 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 27707980]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHøjen AA, Nielsen PB, Overvad TF, Albertsen IE, Klok FA, Rolving N, Søgaard M, Ording AG. Long-Term Management of Pulmonary Embolism: A Review of Consequences, Treatment, and Rehabilitation. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Oct 10:11(19):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11195970. Epub 2022 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 36233833]