Introduction

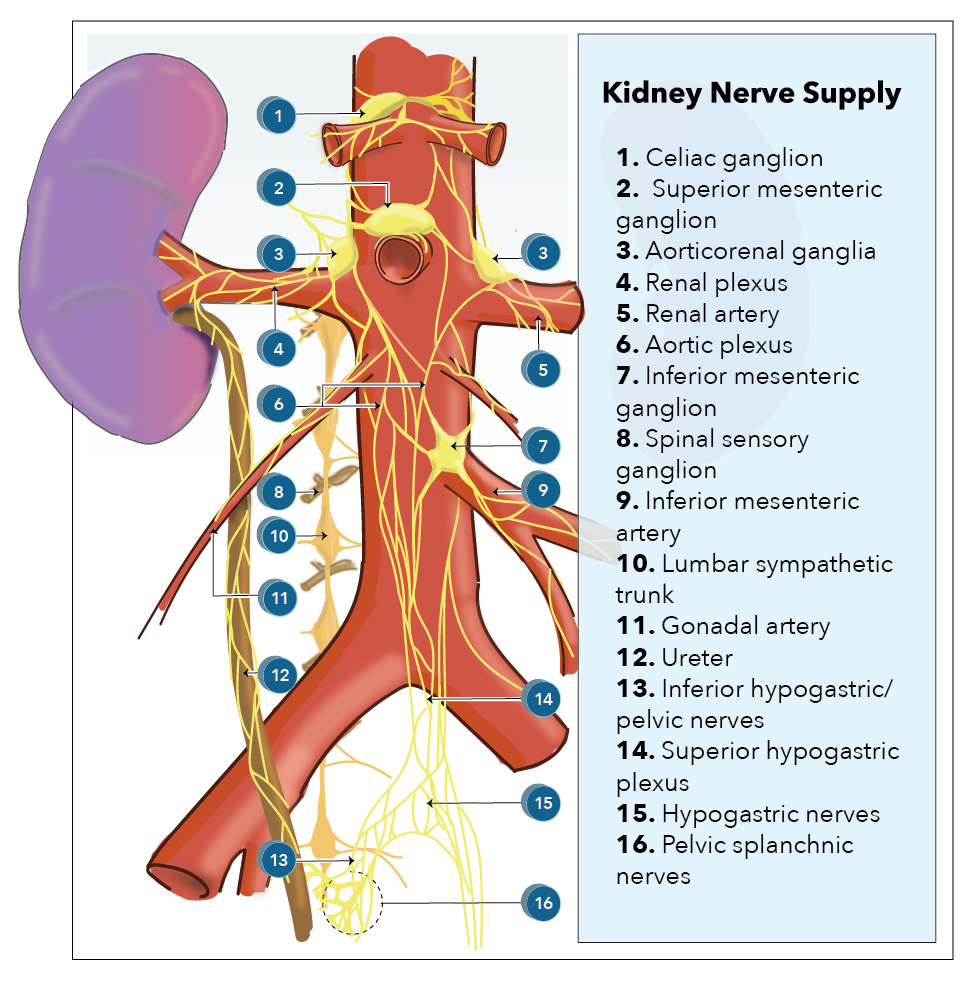

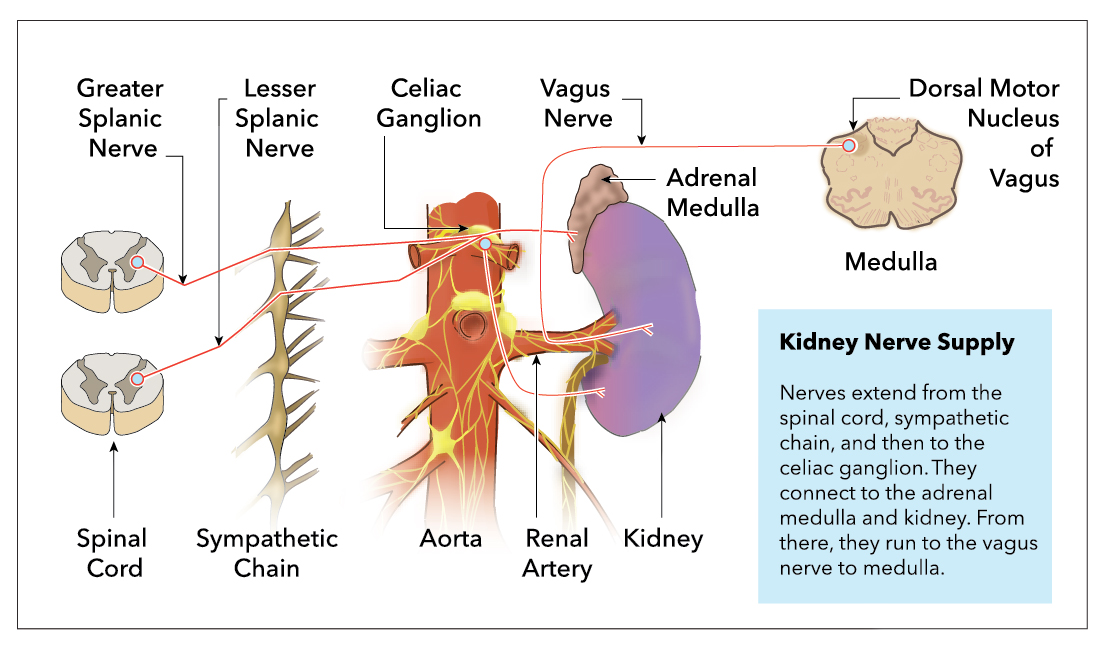

Innervation of the kidney includes both afferent and efferent fibers of the renal plexus. This plexus is a combination of fibers originating from the celiac plexus, intermesenteric plexus, and lumbar splanchnic nerves. [1] Nerves from these plexuses attach along the renal artery and vein, entering the hilus of the kidney. The afferent innervation is essential for nociception recognition. Efferent innervation is primarily sympathetic and receives input from each contributing plexus.[2] Little evidence exists for parasympathetic innervation of the kidney.[1][3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Afferent renal nerves originate from the renal pelvic area at the highest density, but also the renal cortex. These nerves project to some brain regions, including the subfornical organs, the hypothalamus, and brainstem.[4] Afferent fibers are activated by an increase in wall tension. During renal injuries such as ischemia or parenchymal injury, the pain radiates in a dermatomal pattern covering the anterior abdominal wall and flanks.

Sympathetic input to the kidney is one of 3 fundamental mechanisms responsible for the renal regulation of blood pressure, the other 2 being baroreceptor response to blood flow, and control of NaCl concentration by macula densa cells.[5] Sympathetic activity stimulates beta-1 adrenergic receptors located on the juxtaglomerular cells of the kidney. These cells then release renin, thus activating the Renin-angiotensin-Aldosterone System resulting in sodium reabsorption from the nephron. The increase in sodium results in an increase in systemic blood pressure.[6]

Embryology

The embryological development of the kidney is from a cranial to caudal direction and originates from intermediate mesoderm. Early development leads to the urogenital ridge, nephrogenic cord, and, finally, the urinary collection system.

The earliest kidney is pronephros, which appears by four weeks but is nonfunctional. The pronephros is followed by the mesonephros, which forms the Wolffian duct (mesonephric duct). The mesonephros functions as a temporary kidney for most of the first trimester and will eventually contribute to the male genital system.[7]

The metanephros develops from the mesonephric outgrowth and becomes the ureteric bud at around five weeks. It is fully functional and canalized by week two of the pregnancy. This orderly progression of kidney development continues until about 34 to 36 weeks of gestation. The metanephros will give rise to the ureter, renal pelvis, calyces, and collecting ducts. Most anomalies of the kidney develop at this stage of development.

As the metanephros develops, the ureteropelvic junction fuses with the kidney and is the last to canalize. The ureteropelvic junction is the most common anatomical site of obstruction in the fetus leading to hydronephrosis.[8]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The main blood supply to each kidney comes through its respective renal artery. Each renal artery has three critical branches: the inferior adrenal artery, the capsular artery, and the ureteric artery. Additional branches stem from each renal artery as it penetrates the hilum of the kidney, dividing into ventral and dorsal rami and then segmental arteries as they protrude further into the renal parenchyma. Segmental arteries ultimately divide into lobar branches and interlobular arteries. These final arterial segments are critical as the arterioles branching from these segments serve as the afferent arterioles of the glomeruli.[9][10]

Nerves

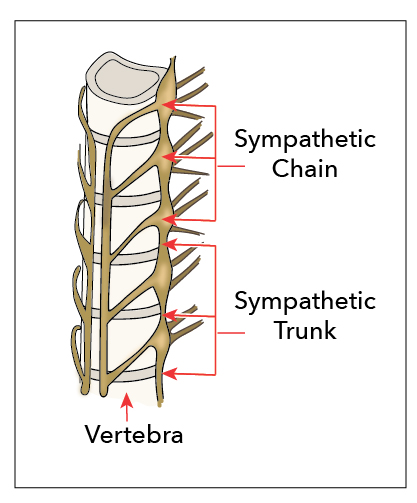

Kidney innervation consists of both afferent and efferent nerves, of which the efferent is strictly sympathetic. These nerves make up the renal plexus, and receive inputs from the celiac and aorticorenal plexuses as well as the least splanchnic nerves. The least splanchnic nerve is primarily responsible for the afferent signaling from the kidney to the brain. The least splanchnic nerve also carries visceral efferent fibers.

Sympathetic input to the organ is brought through visceral efferent fibers and is responsible for stimulating Beta-1-adrenergic receptors in the juxtaglomerular cells of the kidney. This stimulation leads to the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system (RAAS), contributing to the kidney's ability to regulate systemic blood pressure. It is important to note that these nerves are not the exclusive mechanism for blood pressure regulation in the kidney. Baroreceptor response and control of NaCl concentration by macula densa cells are hormonal methods of blood pressure regulation in the kidney.[11][12][13]

Muscles

The retroperitoneum houses the kidneys, just below the diaphragm. The left kidney is usually below the 11th rib extending to L3 while the right kidney is slightly lower between the 12th rib and L3. The lower positioning is due to its placement beneath the liver. Both the left and right kidneys sit on the respective psoas major and quadratus lumborum muscles.[14]

Physiologic Variants

The renal plexus is composed of fibers from the lumbar splanchnic, celiac plexus, and intermestenteric plexus. These fibers, particularly the celiac ganglion, can vary significantly in diameter and size and number of ganglia.[15][16][15]

The lumbar splanchnic nerves typically develop from nerve roots T4-T9; however, the roots can descend to T11 or even skip spinal segment levels.[17]

The position of the kidneys in the retroperitoneum may also vary. An ectopic kidney may be found in the pelvis when it fails to ascend. In rare instances, kidney fusion anomalies may occur, with both kidneys located on the same side. Fused kidneys are associated with ureteropelvic junction obstruction and hydronephrosis.[18]

Surgical Considerations

Renal transplantation destroys fibers of the renal plexus, thus eliminating the sympathetic activity of the kidney. Without sympathetic activity, the Beta-1 adrenergic receptors of juxtaglomerular cells are unable to activate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system. The organ maintains the ability to regulate systemic blood pressure through autoregulatory mechanisms such as the myogenic response and feedback of sodium concentration by the macula densa.[19]

Clinical Significance

In patients with hypertension, there is increased sympathetic activity to the kidneys. This increase leads to increased sodium and water reabsorption, reduction of renal blood flow, and renin release. Longterm overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system can lead to decreased kidney function as well as cardiac hypertrophy.[20]

Renal denervation through sympatho-modulatory approaches is becoming an option for pharmacologically-resistant hypertension. Different from sympathectomies performed in the past, these approaches look to treat hypertension without the adverse effects of postural hypotension. Kidney denervation performed through ultrasound, radiofrequency, or chemical agents has been successful in several clinical trials. Such procedures will likely become more mainstream in the years to come. [20]

Other Issues

To access free multiple-choice questions on this topic, visit statpearls.com.

Media

References

DiBona GF, Kopp UC. Neural control of renal function. Physiological reviews. 1997 Jan:77(1):75-197 [PubMed PMID: 9016301]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBecker BK, Zhang D, Soliman R, Pollock DM. Autonomic nerves and circadian control of renal function. Autonomic neuroscience : basic & clinical. 2019 Mar:217():58-65. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2019.01.003. Epub 2019 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 30704976]

Maeda S, Kuwahara-Otani S, Tanaka K, Hayakawa T, Seki M. Origin of efferent fibers of the renal plexus in the rat autonomic nervous system. The Journal of veterinary medical science. 2014 May:76(5):763-5 [PubMed PMID: 24430660]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCiriello J. Afferent renal inputs onto subfornical organ neurons responsive to angiotensin II. The American journal of physiology. 1997 May:272(5 Pt 2):R1684-9 [PubMed PMID: 9176365]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBurke M, Pabbidi MR, Farley J, Roman RJ. Molecular mechanisms of renal blood flow autoregulation. Current vascular pharmacology. 2014:12(6):845-58 [PubMed PMID: 24066938]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAtlas SA. The renin-angiotensin aldosterone system: pathophysiological role and pharmacologic inhibition. Journal of managed care pharmacy : JMCP. 2007 Oct:13(8 Suppl B):9-20 [PubMed PMID: 17970613]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSeely JC. A brief review of kidney development, maturation, developmental abnormalities, and drug toxicity: juvenile animal relevancy. Journal of toxicologic pathology. 2017 Apr:30(2):125-133. doi: 10.1293/tox.2017-0006. Epub 2017 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 28458450]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReidy KJ, Rosenblum ND. Cell and molecular biology of kidney development. Seminars in nephrology. 2009 Jul:29(4):321-37. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.03.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19615554]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLescay HA, Jiang J, Tuma F. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis Ureter. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422575]

Leslie SW, Sajjad H. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Renal Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083626]

Singh RR, McArdle ZM, Iudica M, Easton LK, Booth LC, May CN, Parkington HC, Lombardo P, Head GA, Lambert G, Moritz KM, Schlaich MP, Denton KM. Sustained Decrease in Blood Pressure and Reduced Anatomical and Functional Reinnervation of Renal Nerves in Hypertensive Sheep 30 Months After Catheter-Based Renal Denervation. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979). 2019 Mar:73(3):718-727. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12250. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30661475]

Nishi EE, Lopes NR, Gomes GN, Perry JC, Sato AYS, Naffah-Mazzacoratti MG, Bergamaschi CT, Campos RR. Renal denervation reduces sympathetic overactivation, brain oxidative stress, and renal injury in rats with renovascular hypertension independent of its effects on reducing blood pressure. Hypertension research : official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension. 2019 May:42(5):628-640. doi: 10.1038/s41440-018-0171-9. Epub 2018 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 30573809]

Campos Munoz A, Vohra S, Gupta M. Orthostasis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422533]

Siccardi MA, Tariq MA, Valle C. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Psoas Major. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571039]

Candal R, Reddy V, Samra NS. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Celiac Ganglia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30844156]

Loukas M, Klaassen Z, Merbs W, Tubbs RS, Gielecki J, Zurada A. A review of the thoracic splanchnic nerves and celiac ganglia. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2010 Jul:23(5):512-22. doi: 10.1002/ca.20964. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20235178]

McCausland C, Sajjad H. Anatomy, Back, Splanchnic Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751046]

Costa A, Matter M, Pascual M, Doerfler A, Venetz JP. [Renal, vascular and urological variations and abnormalities in living kidney donor candidates]. Progres en urologie : journal de l'Association francaise d'urologie et de la Societe francaise d'urologie. 2019 Mar:29(3):166-172. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2018.12.001. Epub 2019 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 30704916]

Carlström M, Wilcox CS, Arendshorst WJ. Renal autoregulation in health and disease. Physiological reviews. 2015 Apr:95(2):405-511. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25834230]

Sata Y, Head GA, Denton K, May CN, Schlaich MP. Role of the Sympathetic Nervous System and Its Modulation in Renal Hypertension. Frontiers in medicine. 2018:5():82. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00082. Epub 2018 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 29651418]