Introduction

Orthodontics seeks to achieve esthetic and functional improvement via mechanical therapy that moves teeth into a more ideal position. Determining the ideal dental position for each patient depends on several factors, such as the facial profile, facial balance, and aesthetic concerns.[1]

In addition to facial problems, orthodontics looks to improve the relationship between the maxillary and mandibular teeth when they come together and function. The biological and functional coordination of how teeth come together is termed occlusion. Over the years, a consensus has been reached on what features are regarded as an ideal or normal occlusion.[2]

However, it is not common to find individuals who exhibit the qualities of an ideal occlusion without receiving orthodontic treatment. Morphological differences in tooth shape and size and sagittal positions of the maxilla and mandible create a plethora of occlusions that an individual can display. Only 8% of cases of malocclusion have a known cause. The remaining 92% have unknown etiology but likely result from environmental and genetic factors.[3]

Classification of Malocclusion

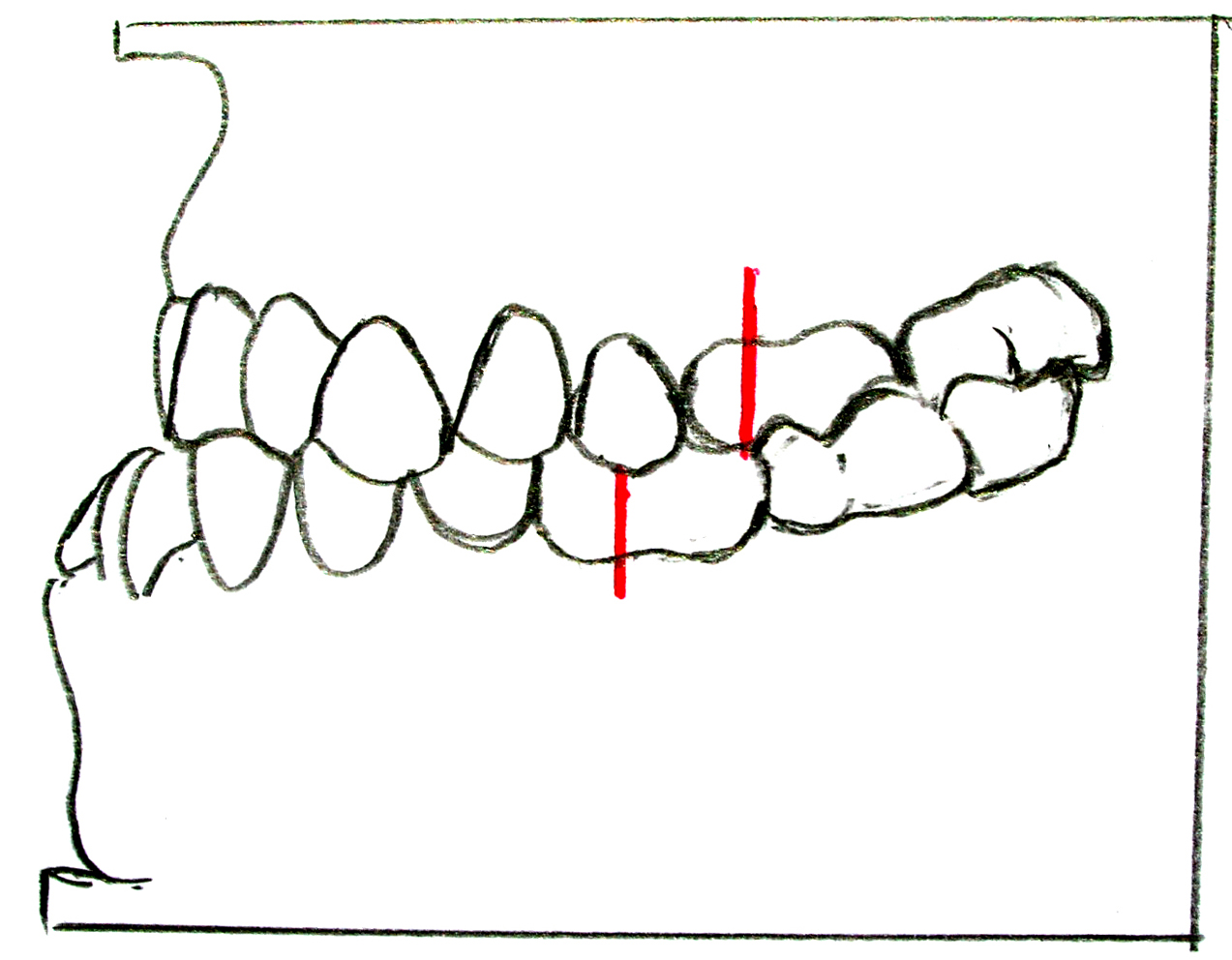

Acknowledged as the "father of modern orthodontics," Dr. Edward Hartley Angle established three classes of malocclusion according to the position of the mesiobuccal cusp of the upper first molar concerning the buccal groove of the lower first molar.

Angle class I molar classification (also known as neutroclusion) is determined by the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar occluding with the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar. A class II molar classification (mesoclusion) is determined by the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar, occluding mesial to the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar. Lastly, a class III molar classification is determined by the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar occluding distal to the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar (distoclusion).[4]

Class I malocclusion is further categorized into three types by Dewey. In Dewey type 1, the incisors are crowded, the canines are positioned labially, or both.[5] In Dewey type 2, the maxillary incisors protrude. In type 3, the anterior teeth occlude edge to edge, or there is a crossbite or both.[5] The Anderson classification further categorizes class I malocclusion into types 4 and 5. In type 4, there is a posterior crossbite, which could be unilateral or bilateral. Type 5 occlusion is a class I molar relationship with mesioversion of the permanent first molar due to the extraction of a second deciduous molar or premolar.[6]

Around 32% of individuals with malocclusion have a class II. A class II molar relationship is when the mandible is positioned retrognathic to the maxilla. Class II interarch relationship is categorized into two divisions. A Class II division 1 is when the maxillary incisors are protruded with an excessive overjet and deep overbite. The maxillary arch is often v-shaped and narrow in the canine region and broad between molar regions. Patients with a class II molar relationship division 1 have a shorter upper lip and often fail to close their anterior lip.

A class II division 2 is when the maxillary central incisors are palatally inclined and may be overlapped by the maxillary lateral incisors. A deep overbite and a broad maxillary arch define a class II division 2. There is a normal upper lip seal and a deep mental groove. Unlike division 1, division 2 has a normal-sized mandible.[7]

A Class III molar relationship occurs when the mandible is positioned anterior to the maxilla. Mandibular teeth protrude over the maxillary teeth. Class III malocclusion is distinguished by the alignment of teeth into three types. In class 3 type 1, the arch is abnormally shaped. In class 3 type 2, the mandibular teeth are tilted lingually. In class 3 type 3, the maxillary teeth are tilted lingually.[8]

Ackerman and Profitt's classification system for malocclusion is used to classify and describe different types of misalignment of the teeth and jaws. It is based on Angle classification.

In Ackerman and Profitt's classification system, malocclusion is divided into classes I, II, III, IV, V, and VI. These categories are based on the relationship between the maxillary and mandibular teeth and the jaw position.

- Class I: The maxillary teeth are slightly forward of the mandibular teeth, and the jaw is aligned properly.

- Class II: The maxillary teeth are significantly forward of the mandibular teeth, and the jaw is underdeveloped.

- Class III: The mandibular teeth are significantly forward of the maxillary teeth, and the jaw is overdeveloped.

- Class IV: The maxillary teeth are significantly behind the mandibular teeth.

- Class V: The maxillary teeth are significantly forward of the mandibular teeth, and the jaw is overdeveloped.

- Class VI: The mandibular teeth are significantly behind the maxillary teeth.[9]

Several skeletal causes of malocclusion may require surgery. These include jaw discrepancies, facial asymmetry, cleft lip and palate, and craniofacial abnormalities. Additionally, although much less common, injury to the face or jaw can cause malocclusion. It is important to note that surgical treatment of malocclusion is typically only recommended in severe cases, and other treatment options, such as braces, may be tried first. A thorough evaluation by an orthodontist or oral and maxillofacial surgeon is needed to determine the most appropriate treatment approach.[10]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of malocclusion is often multifactorial, mainly influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Inherited factors are also believed to be involved, but their exact role is yet to be fully understood.

While most malocclusion cases have an unknown etiology, the correlation between genetics and malocclusion has been studied extensively. Data suggests that a specific malocclusion, Class III mandibular prognathism, is passed down through generations via specific growth factors and genetic markers. Dating back to the 1300s, the heritability pattern of mandibular prognathism can be seen in the European royal Hapsburg family. Nicknamed the “Hapsburg Jaw,” interbreeding between different family members allowed the genes encoding mandibular prognathism to be expressed over multiple generations.[11]

Inherited characteristics can also be factors that influence malocclusion. More specifically, a disproportion between the size of teeth and the size of the jaw can cause crowding or spacing. A disproportion in the size or shape of the maxilla and mandible can also cause malocclusion. The size and shape of teeth and jaws can be inherited together or independently. Studies have shown that the more independently these characteristics are inherited, the more likely there will be a malocclusion disproportion. Compared to primitive generations, malocclusion has become more prevalent as outbreeding between distinct human populations has occurred more frequently. This can be attributed to the fact that these populations inherit discordant characteristics of teeth and jaws.[12]

Environmental factors can play a role in the development of malocclusion as well. This is often seen in children who habitually suck on their thumbs. When pressure is placed against the roof of the mouth, the lower incisors and maxillary molars are pushed lingually, and the upper incisors are pushed labially. Furthermore, the jaw is positioned downward, which allows for posterior teeth to erupt, resulting in a separation of the incisors.[13]

Epidemiology

Malocclusion is often developed when a child begins transitioning into mixed dentition. Overall, there is not a significant difference between males and females. However, female dental eruption and maturation tend to occur faster than males. Therefore it is common for females to receive orthodontic treatment before males.[14]

Studies have shown that the black population has malocclusions more frequently. However, there is no genetic evidence supporting this.[15]

Pathophysiology

Loss of permanent teeth and hypodontia can shift an otherwise ideal occlusion. Hypodontia may be caused by trauma or lack of tooth development. For instance, the loss of a maxillary tooth can allow the eruption of the opposing mandibular tooth into the opposing edentulous space. The adjacent teeth may also tip or shift to the empty space.[16]

Impacted teeth characteristically remain under the gingival tissue and do not erupt into their ideal position. Impacted teeth can be a significant cause of malocclusion, leading to the shifting of adjacent teeth. When impacted teeth do not erupt into the dental arch, additional space exists for adjacent teeth to shift into, which will serve as an obstacle for if and when the impacted tooth may erupt later. Impacted third molars are often experienced during adolescence or early adulthood and may cause interferences in occlusion if not extracted or exposed.[17]

History and Physical

The following qualities define an ideal occlusion: class I molar and canine classification, 1- to 2-mm overjet, 1- to 2-mm overbite, slight to no crowding, and protective guidance movements. Furthermore, the incisal edges and buccal cusps of the teeth in the mandibular arch should align to form a smooth curve.

Likewise, the smooth curve in the maxilla encompasses the central fossae of posterior teeth and the cingulum of the canines and incisors. Other ideal qualities include alignment of the maxillary and mandibular midlines with each other and the face. Angle class I is seen in around 60% of the affected population and is the most commonly seen molar relationship.

Depending on the case, symptoms of malocclusion can vary from mild to severe. Notable signs of malocclusion include misaligned teeth, speech problems, decreased masticatory function and efficiency, alteration from nasal to mouth breathing, and changes in facial structure.[18]

Evaluation

The patient's primary dental provider often evaluates malocclusion. The primary dental provider may be a general dentist, pediatric dentist, or orthodontist. Referalls to the orthodontist are made for patients who exhibit malocclusions that may be detrimental to the patient's dental status and quality of life. A simple oral evaluation is the most common way to diagnose malocclusion; however, radiographs help to evaluate further. Extraoral radiographs, such as the panoramic radiograph and cone-beam computed tomography radiographs, are common types of radiographs taken to examine a patient.[19]

Each imaging method allows the clinician to determine the position of the teeth and evaluate if they are emerging at the right time and place within their respective jaw. CBCT image is beneficial in several ways, especially as it provides a three-dimensional view of the entire face. This allows for a more accurate diagnosis of the malocclusion and permits analysis of a patient's airway and temporomandibular joint.[20]

One such radiograph unique to orthodontics is the cephalometric projection. The cephalometric projections capture a lateral image of the face whereby relationships between the skull and the jaws can be made. These projections can additionally help orthodontists predict the dental age of a patient and growth potential and highlight sagittal discrepancies, all of which can aid treatment planning.[21]

Treatment / Management

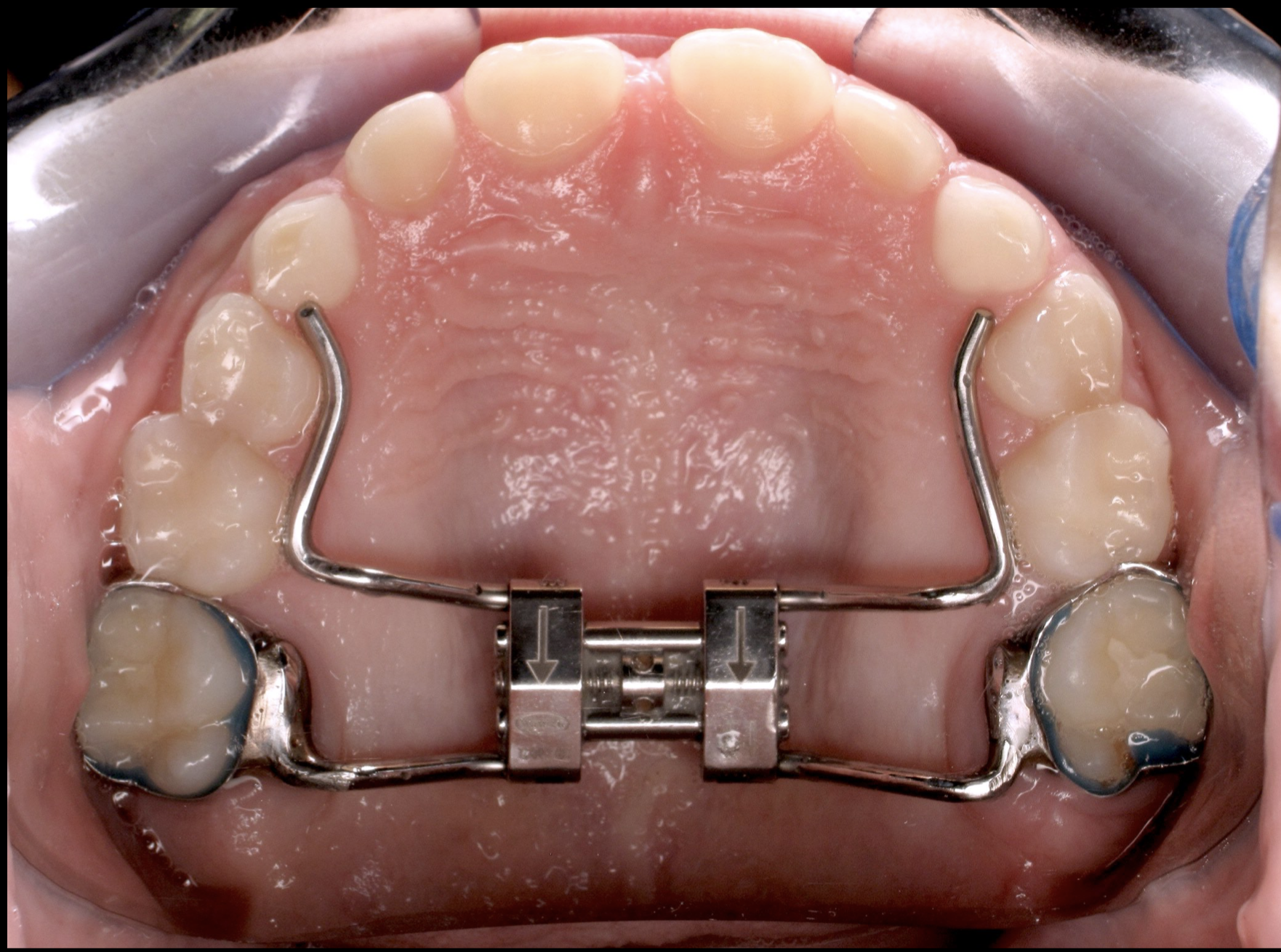

There are several methods to treat malocclusion. Palatal expanders are traditionally used before braces treatment to treat a narrow palate, crowding, or crossbite. Rapid palatal expansion (RPE) works by placing a force on the two maxillary bones to split the mid-palatal suture. Palatal expanders are most useful during adolescence, as the maxillary bones become fused during puberty. The expander contains a screw turned daily or as directed by the patient's orthodontist. Every turn places pressure on the maxillary bone, allowing for less than 1 mm of expansion.[22](A1)

Spacers can be used before or during braces treatment to increase space interproximally. Spacers are normally utilized between molars if there is not enough space for metal bands to be placed around them. Spacers can be made of different materials based on how long they need to be placed in the mouth. Rubber spacers are traditionally used for 1 to 2 weeks and normally fall out as soon as space is adequate. Metal spacers are commonly used for more than six weeks but can also be used for short-term space management.[23](B3)

The traditional way to treat malocclusion is with the use of braces. There are several types of braces made with different materials. Two of the more notable types are metal and ceramic braces. Traditional metal braces consist of brackets placed on teeth that need to be corrected and an archwire that will hold the brackets together. When tightened, the archwire will place pressure on the brackets, allowing the teeth to be aligned and straightened. Ceramic braces are the same as metal braces except that they come in an enamel-like color so that the braces are less noticeable. Brackets can also be made out of stainless steel and gold.[24] For patients concerned with esthetics, lingual braces can be placed. Lingual braces are essentially the same as traditional braces, except the brackets are placed on the lingual surfaces of teeth as opposed to the buccal surfaces.[25](B3)

Over the past few years, clear aligners have become increasingly popular, especially in adult patients. Clear aligners utilize CAD/CAM technology to digitally scan the dental arches to create clear removable trays. A clear aligner treatment has many different sets of aligners, each for a different stage of treatment. Patients wear each stage tray for 1-2 weeks, depending on the treatment plan created by the orthodontist.

Clear aligner treatment is ideal for patients who cannot have many in-person appointments or are concerned with aesthetics. Unfortunately, there are drawbacks to clear aligner treatment, including patient compliance and the severity of the case. Patients are instructed to wear clear aligners for at least 22 hours daily for an optimum time for the teeth to straighten. Additionally, if malocclusion cases are too severe, clear aligners are not recommended, and traditional braces are usually suggested.[26]

While various methods have been proven to treat malocclusion successfully, newer technologies are still being tested to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of treatment. Perhaps in the near future, the utilization of low-level laser therapy on orthodontic movement, for example, will be a common practice in orthodontic offices.[27]

Differential Diagnosis

Potential causes of malocclusion may be considered in the differential diagnosis. Malocclusion can be inherited or caused by the genes one inherits from their parents. Additionally, certain habits, such as thumb sucking or prolonged pacifier use, can cause malocclusion. Skeletal abnormalities, such as abnormalities in the shape or size of the jaw or face, can cause malocclusion. Lastly, missing teeth, inadequate space, and trauma can cause malocclusion.

To determine the cause of malocclusion, a thorough evaluation by an orthodontist is typically necessary. This may include taking a medical history, performing a physical examination, and ordering imaging tests such as panoramic radiographs. Based on the results of this evaluation, a diagnosis and treatment plan can be developed.[28]

Prognosis

Each case of malocclusion treatment is variable, as it depends on the severity of the case, patient compliance, amount of space available in both jaws, and the overall oral health of the patient.[29]

Complications

Complications of untreated malocclusion include tooth decay and increased caries, as crowding can trap food and make it harder for the patient to clean interproximally. Additionally, gingivitis may develop due to plaque buildup. Malocclusion can also cause loss of teeth, impacted teeth, jaw problems, and damage to adjacent and opposing teeth.[30]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Malocclusion can be diagnosed through a visual examination and a radiographic examination of the teeth and face. If a malocclusion occurs, the patient is often referred to an orthodontist. Routine dental appointments can allow for an early diagnosis of malocclusion, which will allow for early treatment. Malocclusion is often hereditary, so it is hard to prevent it. However, parents can prevent environmental factors that can cause malocclusion early on. Such include limiting thumb sucking and stopping bottle and pacifier usage early on.[31]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management and treatment of malocclusion require an interprofessional team of dental healthcare workers, including but not limited to general dentists, dental hygienists, orthodontists, and oral surgeons. An interprofessional team approach to treating malocclusion will allow for earlier diagnosis during routine oral hygiene appointments with a general dentist and dental hygienist.

If a malocclusion is too severe to be treated by a general dentist, a referral can be made for the patient to seek treatment by an orthodontist. In cases of malocclusion requiring surgical treatment, an oral surgeon can work with the orthodontist to correct the misaligned jaw utilizing orthognathic surgery.[32]

Dental hygienists and general dentists play a critical role in monitoring the oral health and state of disease, if applicable, of the patient receiving orthodontic treatment. Many patients who receive traditional braces have a tougher time practicing proper oral hygiene. One of the most commonly neglected sites is the interproximal posterior areas of dentition. Gingivitis may develop if plaque builds up over time in the patient's supragingival and subgingival pockets. Depending on the severity of the disease, oral hygiene instruction and prophylaxis or scaling and root planing may need to be performed by the dentist or dental hygienist.[33] [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Thomas M. Orthodontics in the "Art" of Aesthetics. International journal of orthodontics (Milwaukee, Wis.). 2015 Winter:26(4):23-8 [PubMed PMID: 27029088]

Vlachos CC. Occlusal principles in orthodontics. Dental clinics of North America. 1995 Apr:39(2):363-78 [PubMed PMID: 7781832]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDavies SJ, Gray RM, Sandler PJ, O'Brien KD. Orthodontics and occlusion. British dental journal. 2001 Nov 24:191(10):539-42, 545-9 [PubMed PMID: 11767855]

Hershfeld JJ. Edward H. Angle and the malocclusion of the teeth. Bulletin of the history of dentistry. 1979 Oct:27(2):79-84 [PubMed PMID: 399445]

Devi LB, Keisam A, Singh HP. Malocclusion and occlusal traits among dental and nursing students of Seven North-East states of India. Journal of oral biology and craniofacial research. 2022 Jan-Feb:12(1):86-89. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.10.012. Epub 2021 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 34815931]

Masucci C, Oueiss A, Maniere-Ezvan A, Orthlieb JD, Casazza E. [What is a malocclusion?]. L' Orthodontie francaise. 2020 Jun 1:91(1-2):57-67. doi: 10.1684/orthodfr.2020.11. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33146134]

Uzuner FD, Aslan BI, Dinçer M. Dentoskeletal morphology in adults with Class I, Class II Division 1, or Class II Division 2 malocclusion with increased overbite. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2019 Aug:156(2):248-256.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.03.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31375235]

Ellis E 3rd, McNamara JA Jr. Components of adult Class III malocclusion. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 1984 May:42(5):295-305 [PubMed PMID: 6585502]

Kozanecka A, Sarul M, Kawala B, Antoszewska-Smith J. Objectification of Orthodontic Treatment Needs: Does the Classification of Malocclusions or a History of Orthodontic Treatment Matter? Advances in clinical and experimental medicine : official organ Wroclaw Medical University. 2016 Nov-Dec:25(6):1303-1312. doi: 10.17219/acem/62828. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28028986]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChoi DS, Garagiola U, Kim SG. Current status of the surgery-first approach (part I): concepts and orthodontic protocols. Maxillofacial plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2019 Dec:41(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40902-019-0194-4. Epub 2019 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 30906735]

Xue F, Wong RW, Rabie AB. Genes, genetics, and Class III malocclusion. Orthodontics & craniofacial research. 2010 May:13(2):69-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2010.01485.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20477965]

Cakan DG, Ulkur F, Taner TU. The genetic basis of facial skeletal characteristics and its relation with orthodontics. European journal of dentistry. 2012 Jul:6(3):340-5 [PubMed PMID: 22904665]

Curzon ME. Dental implications of thumb-sucking. Pediatrics. 1974 Aug:54(2):196-200 [PubMed PMID: 4847853]

Lagorsse A, Gebeile-Chauty S. [Does gender make a difference in orthodontics? A literature review]. L' Orthodontie francaise. 2018 Jun:89(2):157-168. doi: 10.1051/orthodfr/2018011. Epub 2018 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 30040615]

Proffit WR, Fields HW Jr, Moray LJ. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: estimates from the NHANES III survey. The International journal of adult orthodontics and orthognathic surgery. 1998:13(2):97-106 [PubMed PMID: 9743642]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElsherif N, Rodriguez J, Ahmed F. Prevalence and management of patients with hypodontia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of orthodontics. 2022 Sep:49(3):332-337. doi: 10.1177/14653125211065457. Epub 2021 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 34903073]

Jain S, Debbarma S, Prasad SV. Prevalence of impacted third molars among orthodontic patients in different malocclusions. Indian journal of dental research : official publication of Indian Society for Dental Research. 2019 Mar-Apr:30(2):238-242. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_62_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31169156]

Bollen AM. Effects of malocclusions and orthodontics on periodontal health: evidence from a systematic review. Journal of dental education. 2008 Aug:72(8):912-8 [PubMed PMID: 18676800]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFoucart JM, Felizardo R, Pizelle C, Bourriau J. [Indications for radiography in orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics]. L' Orthodontie francaise. 2012 Mar:83(1):59-72. doi: 10.1051/orthodfr/2012001. Epub 2012 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 22455651]

Tanna NK, AlMuzaini AAAY, Mupparapu M. Imaging in Orthodontics. Dental clinics of North America. 2021 Jul:65(3):623-641. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2021.02.008. Epub 2021 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 34051933]

Machado GL. CBCT imaging - A boon to orthodontics. The Saudi dental journal. 2015 Jan:27(1):12-21. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2014.08.004. Epub 2014 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 25544810]

Cannavale R, Chiodini P, Perillo L, Piancino MG. Rapid palatal expansion (RPE): Meta-analysis of long-term effects. Orthodontics & craniofacial research. 2018 Nov:21(4):225-235. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12244. Epub 2018 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 30207637]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBowbeer GR. The four dimensions of orthodontic diagnosis--Part II. The Functional orthodontist. 2006 Summer-Fall:23(2):4-6, 8-10, 12-21 [PubMed PMID: 17240935]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRecen D, Yildirim B, Othman E, Comlekoglu E, Aras I. Bond strength of metal brackets to feldspathic ceramic treated with different surface conditioning methods: an in vitro study. European oral research. 2021 Jan 4:55(1):1-7. doi: 10.26650/eor.20210004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33937755]

Huh HH, Chaudhry K, Stevens R, Subramani K. Practice of lingual orthodontics and practitioners' opinion and experience with lingual braces in the United States. Journal of clinical and experimental dentistry. 2021 Aug:13(8):e789-e794. doi: 10.4317/jced.58328. Epub 2021 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 34512918]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKe Y, Zhu Y, Zhu M. A comparison of treatment effectiveness between clear aligner and fixed appliance therapies. BMC oral health. 2019 Jan 23:19(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0695-z. Epub 2019 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 30674307]

Karabel MA, Doğru M, Doğru A, Karadede Mİ, Tuncer MC. Evaluation of the effects of diode laser application on experimental orthodontic tooth movements in rats. Histopathological analysis. Acta cirurgica brasileira. 2021:35(12):e351204. doi: 10.1590/ACB351204. Epub 2021 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 33503217]

Rapeepattana S, Thearmontree A, Suntornlohanakul S. Etiology of Malocclusion and Dominant Orthodontic Problems in Mixed Dentition: A Cross-sectional Study in a Group of Thai Children Aged 8-9 Years. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry. 2019 Jul-Aug:9(4):383-389. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_120_19. Epub 2019 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 31516872]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceManosudprasit A, Haghi A, Allareddy V, Masoud MI. Diagnosis and treatment planning of orthodontic patients with 3-dimensional dentofacial records. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2017 Jun:151(6):1083-1091. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.10.037. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28554454]

Ruhl CM, Bellian KT, Van Meter BH, Hoard MA, Pham CD, Edlich RF. Diagnosis, complications, and treatment of dentoskeletal malocclusion. The American journal of emergency medicine. 1994 Jan:12(1):98-104 [PubMed PMID: 8285988]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStaufert Gutierrez D, Carugno P. Thumb Sucking. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310572]

Chu I, Kennedy D, Hatzimanolakis P. Knowledge of malocclusion supports comprehensive dental hygiene care. Canadian journal of dental hygiene : CJDH = Journal canadien de l'hygiene dentaire : JCHD. 2019 Jun 1:53(2):118-124 [PubMed PMID: 33240349]

Rosa EP, Murakami-Malaquias-Silva F, Schalch TO, Teixeira DB, Horliana RF, Tortamano A, Tortamano IP, Buscariolo IA, Longo PL, Negreiros RM, Bussadori SK, Motta LJ, Horliana ACRT. Efficacy of photodynamic therapy and periodontal treatment in patients with gingivitis and fixed orthodontic appliances: Protocol of randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Medicine. 2020 Apr:99(14):e19429. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019429. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32243363]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence