Introduction

A herniated disc in the spine is a condition during which a nucleus pulposus is displaced from intervertebral space. It is a common cause of back pain. The patients who experience pain related to a herniated disc often remember an inciting event that caused their pain. Unlike mechanical back pain, herniated disc pain is often burning or stinging and may radiate into the lower extremities. Furthermore, in more severe cases, there can be associated with weakness or sensation changes. In the spine, a disc or a nucleus pulposus is localized between vertebral bodies. It supports the spine by acting as a shock-absorbing cushion. In some instances, a herniated disc injury can compress the nerve or the spinal cord, causing pain consistent with nerve compression or spinal cord dysfunction, also known as myelopathy. Herniated discs can be very painful.

Unfortunately, there are limited effective conservative treatment modalities with significant effectiveness. Within a few weeks, most cases of painful disc herniation heal. In many instances, the herniation of the disc does not cause that patient any pain. Herniated discs are often seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients who are asymptomatic. Imaging is not indicated in a patient with signs and symptoms of a stable herniated disc until 6 weeks of persistent symptoms. MRI is the imaging modality of choice. Most cases of herniated disc heal conservatively, but refractory cases may require interventional procedures or surgical repair. Epidural corticosteroid injections are effective pain relievers for disc herniation in the short term, while discectomy is more effective than conservative management until one year following surgery [1][2][3]. Providers need to remain aware of treating the patient with a herniated disc and monitor for severe or rapidly progressing neurological changes; this would be an indication for urgent neurosurgical referral.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

An intervertebral disc is composed of annulus fibrous—the annulus fibrous, dense collagenous ring encircling the nucleus pulposus. Disc herniation occurs when part or all of the nucleus pulposus protrudes through the annulus fibrous. The most common cause of disc herniation is a degenerative process in which, as humans age, the nucleus pulposus becomes less hydrated and weakens. This process will lead to a progressive disc herniation that can cause symptoms. The second most common cause of disc herniation is trauma. Other causes include connective tissue disorders and congenital disorders such as short pedicles. Disc herniation is most common in the lumbar spine, followed by the cervical spine. There is a higher rate of disc herniation in the lumbar and cervical spine due to the biomechanical forces in the flexible part of the spine. The thoracic spine has a lower rate of disc herniation[4][5].

The pathophysiology of herniated discs is believed to be a combination of the mechanical compression of the nerve by the bulging nucleus pulposus and the local increase in inflammatory chemokines. A herniation is more likely to occur posterolaterally, where the annulus fibrosus is thinner and lacks structural support from the anterior or posterior longitudinal ligaments. Due to its proximity, a posterolateral herniation is more likely to compress the nerve root. On the other hand, spinal cord compression and clinical myelopathy can occur if there is a herniation of a large midline disc. The localized back pain is a combination of the herniated disc pressure on the longitudinal ligament and chemical irritation due to local inflammation.

Epidemiology

The incidence of a herniated disc is about 5 to 20 cases per 1000 adults annually and is most common in people in their third to fifth decade of life, with a man-woman ratio of 2:1 [6]. The estimated prevalence of symptomatic herniated discs of the lumbar spine is about 1% to 3% of patients. The prevalence is most significant among 30-50-year-olds. Patients between 25 and 55 years old have an approximately 95% chance of herniated discs occurring either at L4-L5 or L5-S1 [7]. Disc disease is the underlying etiology in less than five percent of patients with back pain [8].

History and Physical

There are characteristic findings of herniated discs all along the vertebrae. The patient will likely recall an inciting injury, often due to lifting or twisting. Furthermore, pain can be described as sharp or burning. There is often radiation of the pain in the distribution of the compressed nerve root. Numbness and tingling, as well as decreased sensation along the path of the nerve root, may also occur. In more severe cases, weakness or a feeling of instability while ambulating may be endorsed.

Cervical Spine

History

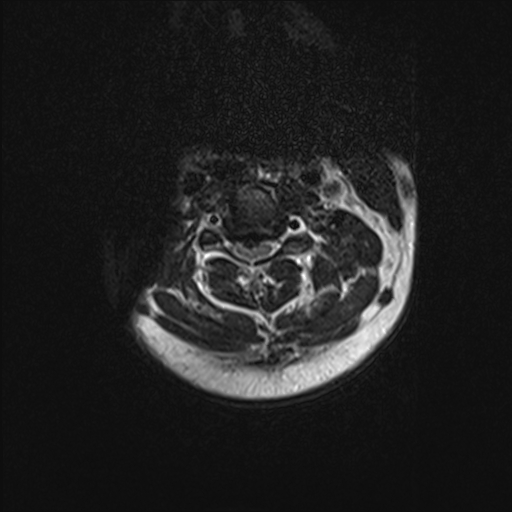

In the cervical spine, the C6-7 is the most common herniation disc that causes symptoms, mostly radiculopathy (see Image. Cervical Spine, Magnetic Resonance Image). History in these patients should include the chief complaint, the onset of symptoms, and where the pain starts and radiates. History should include if there are any past treatments.[9]

Physical Examination

On physical examination, particular attention should be given to weaknesses and sensory disturbances, and their myotome and dermatomal distribution. The examiner should also pay attention at this point to any sign of spinal cord dysfunction.

Typical findings of solitary nerve lesion due to compression by a herniated disc in the cervical spine

- C5 nerve: Neck, shoulder, and scapula pain, lateral arm numbness, and weakness during shoulder abduction, external rotation, elbow flexion, and forearm supination. The reflexes affected are the biceps and brachioradialis.

- C6 nerve: Neck, shoulder, scapula, and lateral arm, forearm, and hand pain, along with lateral forearm, thumb, and index finger numbness. Weakness during shoulder abduction, external rotation, elbow flexion, and forearm supination and pronation are common. The reflexes affected are the biceps and brachioradialis.

- C7 nerve: Neck, shoulder, and middle finger pain are standard, along with the index, middle finger, and palm numbness. Weakness on the elbow and wrist is common, along with weakness during radial extension, forearm pronation, and wrist flexion may occur. The reflex affected is the triceps.

- C8 nerve: Neck, shoulder, and medial forearm pain, with numbness on the medial forearm and medial hand. Weakness is common during finger extension, wrist (ulnar) extension, distal finger flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction, along with distal thumb flexion. No reflexes are affected.

- T1 nerve: Pain is common in the neck, medial arm, and forearm, whereas numbness is common in the anterior arm and medial forearm. Weakness can occur during thumb abduction, distal thumb flexion, finger abduction, and adduction. No reflexes are affected.

Thoracic Spine

Intervertebral disc degeneration often causes thoracic discogenic pain syndrome. Thoracic disc lesions mostly affect the lower part of the thoracic spine. Three-quarters of incidence occurs below T8, and T11-T12 are most common.

History

Most thoracic disc herniations are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally with an MRI.Unlike the lumbar and cervical disc herniations, thoracic disc herniations have atypical symptoms and are often a diagnosis of exclusion.

Physical Examination

Patients may have sensory changes. Serious findings include gait disturbances, paralysis, and cardiovascular abnormalities.

Lumbar Spine

History

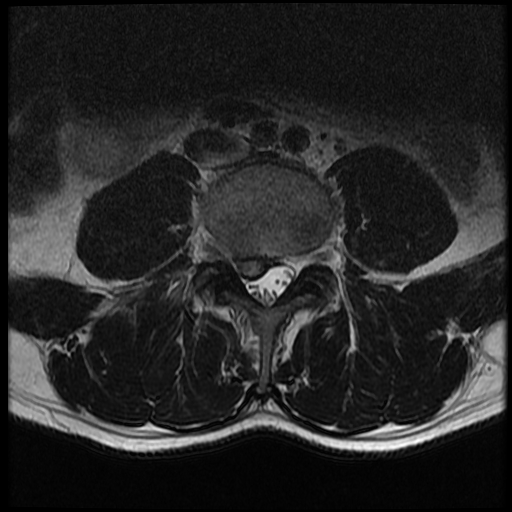

In the lumbar spine, a herniated disc can present with symptoms, including sensory and motor abnormalities limited to a specific myotome (see Image. Lumbar Spine Disc Herniation, Magnetic Resonance Image). History in these patients should include chief complaints, the onset of symptoms, and where the pain starts and radiates. History should include if there are any past treatments.

Physical Examination

A careful neurological examination can help in localizing the level of the compression. The sensory loss, weakness, pain location, and reflex loss associated with the different levels are described below.

Typical findings of solitary nerve lesion due to compression by a herniated disc in the lumbar spine

- L1 nerve: Pain and sensory loss are common in the inguinal region. Hip flexion weakness is rare, and no stretch reflex is affected.

- L2-L4 nerves: Back pain radiating into the anterior thigh and medial lower leg; sensory loss to the anterior thigh and sometimes medial lower leg; hip flexion and adduction weakness; knee extension weakness; and decreased patellar reflex.

- L5 nerve: Back, radiating into buttock, lateral thigh, lateral calf, and dorsum foot, great toe; sensory loss on the lateral calf, dorsum of the foot, webspace between first and second toe; weakness on hip abduction, knee flexion, foot dorsiflexion, toe extension and flexion, foot inversion and eversion; decreased semitendinosus/semimembranosus reflex.

- S1 nerve: Back, radiating into buttock, lateral or posterior thigh, posterior calf, lateral or plantar foot; sensory loss on the posterior calf, lateral or plantar aspect of foot; weakness on hip extension, knee flexion, plantar flexion of the foot; Achilles tendon; Medial buttock, perineal, and perianal region; weakness may be minimal, with urinary and fecal incontinence as well as sexual dysfunction.

- S2-S4 nerves: Sacral or buttock pain radiating into the posterior aspect of the leg or the perineum; sensory deficit on the medial buttock, perineal, and perianal region; absent bulbocavernosus, anal wink reflex.

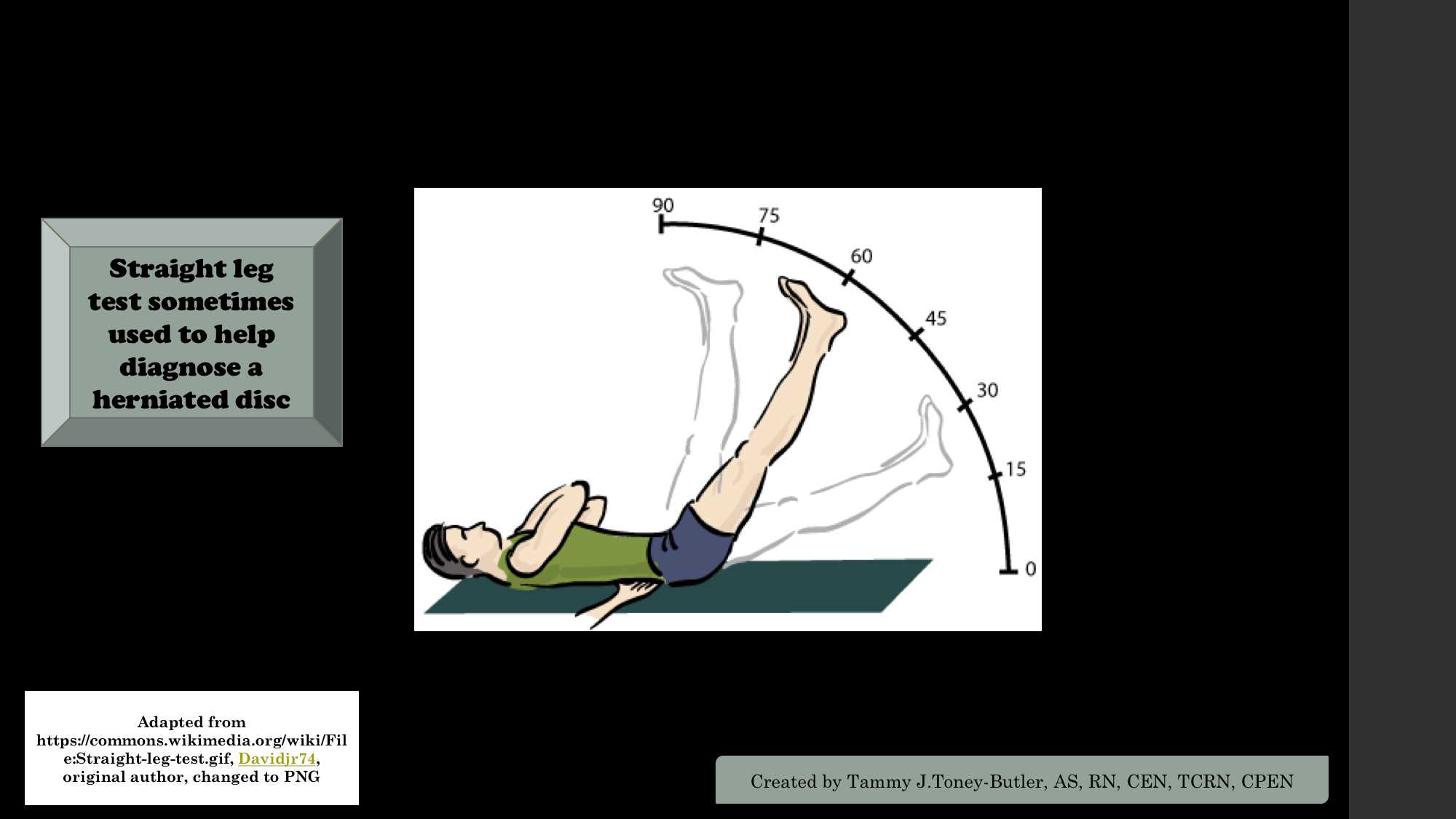

The straight leg raise test: With the patient lying supine, the examiner slowly elevates the patient's leg at an increasing angle while keeping the leg straight at the knee joint. The test is positive if it reproduces the patient's typical pain and paresthesia.[10] See Image. Straight Leg Test.

The contralateral (crossed) straight leg raise test: As in the straight leg raise test, the patient is lying supine, and the examiner elevates the asymptomatic leg. The test is positive if the maneuver reproduces the patient's typical pain and paresthesia. The test has a specificity higher than 90%.

Evaluation

Over 85% of patients with symptoms associated with an acute herniated disc will resolve within 8 to 12 weeks without any specific treatments. However, patients who have an abnormal neurological examination or are refractory to conservative treatments will need further evaluation and treatments.[11][12][13]

X-rays: These are very accessible at most clinics and outpatient offices. This imaging technique can be used to assess for any structural instability. If x-rays show an acute fracture, it needs to be further investigated using a computed tomogram (CT) scan or MRI.

CT scan: It is the preferred study to visualize bony structures in the spine. It can also show calcified herniated discs. It is less accessible in office settings compared to x-rays. But it is more convenient than MRI. In patients that have non-MRI comparable implanted devices, CT myelography can be performed to visualize herniated discs.

MRI: It is the preferred and most sensitive study to visualize herniated discs. MRI findings will help surgeons and other providers plan procedural care if it is indicated.

Treatment / Management

Conservative Treatments

Acute cervical and lumbar radiculopathies due to a herniated disc are primarily managed with non-surgical treatments. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy are first-line treatment modalities. Physical therapy is not recommended on the initial onset of symptoms. Most cases of disc herniation resolve within a few weeks after the onset of symptoms; thus, it is not recommended to start physical therapy until symptoms have lasted for at least 3 weeks. These are excellent modalities for managing disabling pain. Patients who fail conservative treatment or patients with neurological deficits need timely surgical consultation. [14][15][16][17] There is limited evidence for the use of muscle relaxers such as cyclobenzaprine or oral corticosteroids [18]. For cases of severe pain unresponsive to over-the-counter pain medication, opioid analgesics are warranted. However, the side effect profile, risks, and benefits of the medicine should be discussed with the patient, and opioids should be prescribed for the shortest duration possible. Translaminar epidural injections and selective nerve root blocks are the second-line modalities for patients unresponsive to conservative management and who have had symptoms for at least four to six weeks. There is limited evidence of the efficacy of epidural injections beyond 3 months, but repeat injections are often considered as well [19][20].(A1)

Surgical Treatments

As always, surgical treatment is the last resort. Surgical procedures for a herniated disc include laminectomies with discectomies depending on the cervical or lumbar area. Also, a patient with a herniated disc in the cervical spine can be managed via an anterior approach that requires anterior cervical decompression and fusion. An artificial disk replacement option can be considered. Other alternative surgical procedures to the lumbar spine include a lateral or anterior approach that requires complete discectomy and fusion. The benefits of surgical intervention are moderate and tend to decrease over time following surgery [21].(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for a herniated disc include:

- Discal cyst

- Mechanical back pain

- Degenerative spinal stenosis

- Epidural abscess

- Epidural hematoma

- Metastasis

- Diabetic amyotrophy

- Neurinoma

- Osteophytes

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Synovial cyst

Prognosis

Studies vary on outcomes of herniated disc prognosis. However, most cases respond to conservative management. One study's results did show that 30% of patients complain of back pain at one year [22]. It should also be mentioned that many cases of disc herniation are asymptomatic and found inadvertently on advanced imaging. Of symptomatic cases, 90% of them resolved at 6 weeks following injury. Surgery may lead to more rapid recovery of the symptomatic herniated disc, but results are also similar to conservative management at 1 year post-operatively [23][24][23].

Complications

Complications of a herniated disc include the development of chronic back pain. Furthermore, untreated cases of disc herniation, albeit rare, can lead to lasting nerve damage in severe nerve root compression. Most examples of discectomy are successful in the surgical repair of a herniated disc, but some cases do require repeat intervention. Economically symptomatic herniated discs can lead to significant loss of work and disability. A severe complication of surgery or interventional procedures is rare, but cases of paralysis and death have been recorded in the literature.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The following information is uselful for educating patients on disc herniation:

- Thoracic spine herniated discs usually present with radiculopathy symptoms or myelopathic symptoms depending on the compression of the nerve roots or spinal cord, respectively.

- Patients may complain of burning pain, numbness, tingling, sensation changes, or weakness.

- The vast majority of cases are resolved with conservative management.

- In the cervical (neck) and lumbar (low back) spine, patients initially are managed conservatively with over-the-counter pain medications, home exercises, heat, ice, and activity as tolerated.

- The time of recovery often depends on the mechanism of injury, as well as the severity of disc herniation. On average, most cases of disc herniation resolve between two to twelve weeks following injury.

- Since many cases improve within 2 to 3 weeks following injury, physical therapy is not recommended until 3 weeks after the onset of symptoms.

- Similarly, given that most cases resolve within 6 weeks of symptoms. An MRI is not recommended until at least 6 weeks of persistent symptoms, symptoms of severe radiculopathy, or rapidly worsening neurological changes associated with a suspected disc herniation.

- A patient who has progressive myelopathic symptoms or does not respond to conservative treatment can be managed with an epidural steroid injection or radiofrequency ablative techniques.

- The surgical approach for the thoracic spine includes the transthoracic or costotransversectomy approach for discectomies and fusion.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Disc herniation is a common problem encountered by the primary care provider, nurse practitioner, emergency department physician, and internist. The management of disc herniation is not satisfactory, and thus, an interprofessional team needs to be involved. The initial treatment should be conservative unless a patient has a severe neurological compromise. The patient's pain is often managed with acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories. However, some cases require opioid analgesics. A pharmacist should monitor the duration and dosage of opioid analgesics. Surgery is usually the last resort, as it does not always result in predictable results. Patients are often left with residual pain and neurological deficits, which are often worse after surgery. Physical therapy is vital for most patients. For refractory cases, MRI interpretation is needed by a radiologist.

Furthermore, cases unresponsive to conservative management may require either the expertise of a pain medicine specialist in stable cases or a neurosurgeon in unstable instances. Back pain can be a significant cause of morbidity and is often associated with mental health disorders. Chronic back pain is associated with depression and should be managed accordingly by the primary care or mental health clinician. The outcomes depend on many factors, but those who participate in regular exercise and maintain a healthy body weight have better results than people who are sedentary[25][1][26][6].

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sharma SB, Kim JS. A Review of Minimally Invasive Surgical Techniques for the Management of Thoracic Disc Herniations. Neurospine. 2019 Mar:16(1):24-33. doi: 10.14245/ns.1938014.007. Epub 2019 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 30943704]

Huang R, Meng Z, Cao Y, Yu J, Wang S, Luo C, Yu L, Xu Y, Sun Y, Jiang L. Nonsurgical medical treatment in the management of pain due to lumbar disc prolapse: A network meta-analysis. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2019 Oct:49(2):303-313. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.02.012. Epub 2019 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 30940466]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTang C, Moser FG, Reveille J, Bruckel J, Weisman MH. Cauda Equina Syndrome in Ankylosing Spondylitis: Challenges in Diagnosis, Management, and Pathogenesis. The Journal of rheumatology. 2019 Dec:46(12):1582-1588. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.181259. Epub 2019 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 30936280]

Park CH, Park ES, Lee SH, Lee KK, Kwon YK, Kang MS, Lee SY, Shin YH. Risk Factors for Early Recurrence After Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Disc Decompression. Pain physician. 2019 Mar:22(2):E133-E138 [PubMed PMID: 30921991]

Huang JS, Fan BK, Liu JM. [Overview of risk factors for failed percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy in lumbar disc herniation]. Zhongguo gu shang = China journal of orthopaedics and traumatology. 2019 Feb 25:32(2):186-189. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-0034.2019.02.019. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30884940]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFjeld OR, Grøvle L, Helgeland J, Småstuen MC, Solberg TK, Zwart JA, Grotle M. Complications, reoperations, readmissions, and length of hospital stay in 34 639 surgical cases of lumbar disc herniation. The bone & joint journal. 2019 Apr:101-B(4):470-477. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B4.BJJ-2018-1184.R1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30929479]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJordan J, Konstantinou K, O'Dowd J. Herniated lumbar disc. BMJ clinical evidence. 2009 Mar 26:2009():. pii: 1118. Epub 2009 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 19445754]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. The prevalence and clinical features of internal disc disruption in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995 Sep 1:20(17):1878-83 [PubMed PMID: 8560335]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDydyk AM, Khan MZ, Singh P. Radicular Back Pain. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536200]

Das JM, Dua A, Nadi M. Straight Leg Raise Test (Lasegue sign). StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424883]

Carlson BB, Albert TJ. Lumbar disc herniation: what has the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial taught us? International orthopaedics. 2019 Apr:43(4):853-859. doi: 10.1007/s00264-019-04309-x. Epub 2019 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 30767043]

Hassan KZ, Sherman AL. Epidural Steroids. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30726005]

Johnson SM, Shah LM. Imaging of Acute Low Back Pain. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2019 Mar:57(2):397-413. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2018.10.001. Epub 2018 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 30709477]

Brazilian Medical Association, Silvinato A, Simões RS, Buzzini RF, Bernardo WM. Lumbar herniated disc treatment with percutaneous hydrodiscectomy. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira (1992). 2018 Sep:64(9):778-782. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.64.09.778. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30672996]

Harper R, Klineberg E. The evidence-based approach for surgical complications in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation. International orthopaedics. 2019 Apr:43(4):975-980. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4255-6. Epub 2018 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 30543041]

Lavi ES, Pal A, Bleicher D, Kang K, Sidani C. MR Imaging of the Spine: Urgent and Emergent Indications. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2018 Dec:39(6):551-569. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2018.10.006. Epub 2018 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 30527521]

Alvin MD, Lubelski D, Alam R, Williams SK, Obuchowski NA, Steinmetz MP, Wang JC, Melillo AJ, Pahwa A, Benzel EC, Modic MT, Quencer R, Mroz TE. Spine Surgeon Treatment Variability: The Impact on Costs. Global spine journal. 2018 Aug:8(5):498-506. doi: 10.1177/2192568217739610. Epub 2017 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 30258756]

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians, Denberg TD, Barry MJ, Boyd C, Chow RD, Fitterman N, Harris RP, Humphrey LL, Vijan S. Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2017 Apr 4:166(7):514-530. doi: 10.7326/M16-2367. Epub 2017 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 28192789]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLandau WM, Nelson DA, Armon C, Argoff CE, Samuels J, Backonja MM. Assessment: use of epidural steroid injections to treat radicular lumbosacral pain: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2007 Aug 7:69(6):614; author reply 614-5 [PubMed PMID: 17679685]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, Fu R, Bougatsos C, Dana T, Sullivan SD, Jarvik J. Epidural Corticosteroid Injections for Radiculopathy and Spinal Stenosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2015 Sep 1:163(5):373-81. doi: 10.7326/M15-0934. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26302454]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, Rosenquist RW, Atlas SJ, Baisden J, Carragee EJ, Grabois M, Murphy DR, Resnick DK, Stanos SP, Shaffer WO, Wall EM, American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guideline Panel. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine. 2009 May 1:34(10):1066-77. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a1390d. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19363457]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAmlie E, Weber H, Holme I. Treatment of acute low-back pain with piroxicam: results of a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Spine. 1987 Jun:12(5):473-6 [PubMed PMID: 2957801]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchoenfeld AJ, Weiner BK. Treatment of lumbar disc herniation: Evidence-based practice. International journal of general medicine. 2010 Jul 21:3():209-14 [PubMed PMID: 20689695]

Buttermann GR. Treatment of lumbar disc herniation: epidural steroid injection compared with discectomy. A prospective, randomized study. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2004 Apr:86(4):670-9 [PubMed PMID: 15069129]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHeo DH, Sharma S, Park CK. Endoscopic Treatment of Extraforaminal Entrapment of L5 Nerve Root (Far Out Syndrome) by Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Approach: Technical Report and Preliminary Clinical Results. Neurospine. 2019 Mar:16(1):130-137. doi: 10.14245/ns.1938026.013. Epub 2019 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 30943715]

Shen Z, Zhong ZM, Wu Q, Zheng S, Shen X, Chen J. Predictors for Poor Outcomes After Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy: A Retrospective Study of 241 Patients. World neurosurgery. 2019 Jun:126():e422-e431. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.02.068. Epub 2019 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 30825632]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSegato G,Fazzini G,Dall [PubMed PMID: 5737773]