Introduction

Bone is a specialized complex, living connective tissue that supports the body and protects vital organs of the body.[1][2] Impregnation of the extracellular matrix with the inorganic salts like calcium phosphate and carbonate provides hardness to the bone.[3]

Types of Bones: Histologically, bones categorize into two types (1) cortical or compact bone and (2) cancellous bone or spongy bone.

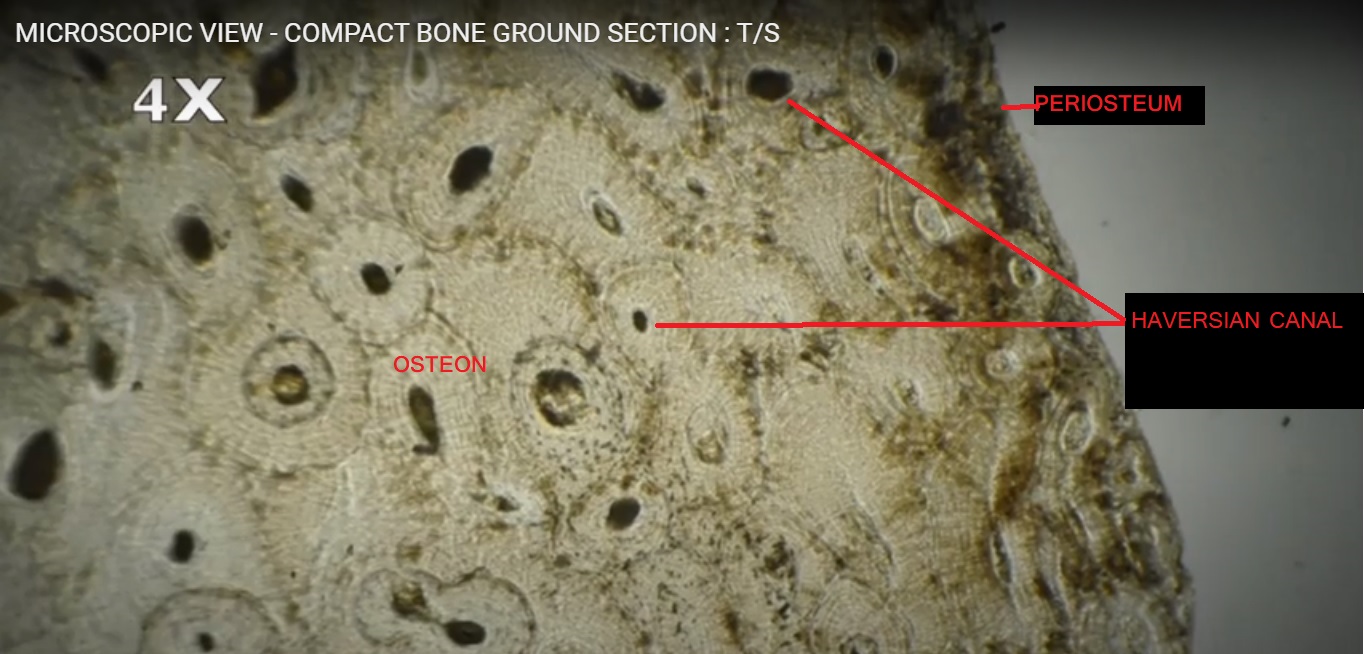

Compact Bone (IMAGE 1): The shaft of the long bone like femur has a cavity known as a bone marrow cavity; the cavity is walled by dense material. The dense material is of uniform smooth texture without any cavity within is known as the compact bone. Compact bone slowly changes according to the stress, tension, and other mechanical forces.[4][5][6]

Cancellous bone: The ends of the long bones are devoid of the marrow cavity. Instead, they are populated with mesh-like structure made up of plates and rods; it contains numerous minute spaces. The structure gives a sponge-like appearance, so this type of bone is known as cancellous or spongy bone. Spongy bone has a larger surface area and a high metabolic rate.[7][8][6]

Bone is a vascular structure and has a nervous supply also. The outer covering of the bone is known as the periosteum; the periosteum covers the whole surface of the bone except at the ligament attachment, tendon attachment, and an area covered by articulating cartilage. The periosteum is absent in sesamoid bones.[9][10]

A membrane lining the wall of the bone marrow cavity is known as the endosteum.[11]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Bones are crucial for skeletal support to the body; it is a site of hemopoietic cells and a reservoir of calcium and phosphate.[11]

The periosteum and endosteum are essential for growing, fracture healing, and remodeling of the bone.[12] The functional state of the bone dictates the noticeable variations in the periosteum’s microscopic appearance.[13][11]

Periosteum and endosteum contain cells (osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteoprogenitor cells) required for bone development and remodeling of the bone. Understanding the histology of the endosteum and periosteum will help to decode the pathological conditions of bone.

Structure

Periosteum: The periosteum consists of two layers; Outer fibrous membrane and inner cellular layer.[6]

Outer fibrous layer: Outer is an irregular, dense connective tissue type with more collagenous matrix and less number of cells.[14][6][15] The outer layer further subdivides into a superficial and deep layer; the superficial layer is more vascular and receives periosteal vessels, while the inner layer is a fibro-elastic layer.[15][14][6][16]

The inner cellular layer of the periosteum is also described as the inner cambium layer by some authors. It is made up of osteoprogenitor cells (fibroblast-like cells); it is also known as the osteogenetic layer. [14] The Inner layer contains osteoblasts in young developing bones. [14][17] Although in adult bones, osteoblasts may be absent, they appear whenever required (e.g., fracture healing). [12] Osteoprogenitor cells are multipotent stem cells; they can undergo mitotic division and differentiate into osteoblasts by taking up thymidine.[17][18][17] The inner layer is also a rich vascular structure with many microvessels; stimulated pericytes derived from the endothelium of these microvessels may augment the osteoblast formation from the osteoprogenitor cells.[19]

Blood vessels supplying the periosteum hold a small caliber and branches in to supply the Haversian and Volkmann canals. Sharpey’s fibers, clusters of periosteal collagen fibers, protrude the bone matrix and bind the periosteum to the bone. These fibers exist more at the attachment of ligaments and tendons to bone. [14]

The periosteum is thick in initial years of life; the thickness of the periosteum decreases as age advances. Periosteum thickness differs with the site of the bone also.[20] The periosteum is not present in sesamoid types of bones.[21][22]

Endosteum: A membrane lining the inner surface of the bony wall also identified as the lining membrane of the Bone marrow cavity is endosteum; The endosteum lines the Haversian canal and all the internal cavities of the bone. The endosteum consists of a layer of flattened osteoprogenitor cells and a type-III collagenous fibers (reticular fibers).[23][18] The endosteum is noticeably thinner than the periosteum.[24][18]

Endosteum is classified into three types based on their site: (i) Cortical endosteum: endosteum lining the bone marrow cavity, (ii) Osteon endosteum: Endosteum lining the osteons mainly contains nerves and blood vessels. (iii) Trabecular endosteum: Lines the trabecula near the developing part of the bone. It plays a role in the growth and development of the bone.[25][26][27][28][13][29]

Function

- Nutrition to the bony tissue: periosteal blood vessel supplies the bony wall and internal osseous tissue up to some extent.[30] Nerves characterize the vessels that supply the bone and its periosteum. The majority of the nerves flowing along the internal cavity with the nutrient artery are vasomotor fibers that control blood flow.[1]

- Bone growth: During the development of the bone, the periosteum is thick and contains osteoprogenitor cells; Osteoblasts differentiated from the osteoprogenitor cells are crucial for the appositional growth of the bone.[18] Endosteum plays a role in the formation of an internal matrix by absorption and deposition of tissue.[6] The endosteum stimulates the uninterrupted internal bone resorption. The medullary canal, along with the overall bone diameter, increases because of endosteum-stimulated resorption.[31][32] Endosteal endoblasts secrete bone matrix and compose ridges beside the periosteal blood vessels. The bony ridges expand and fuse to convert the groove into a vascularized tunnel. Endosteal osteoblasts compose new lamellae and form new osteons. Finally, a new circumferential lamella appears beneath the periosteum. This process repeats for continuous bone diameter enlargement, which slows down with adulthood.[33]

- Repair: Osteoprogenitor cells present in the periosteum are multipotent stem cells (MSC) that can induce bone development whenever required, like with a fracture of the bone.[34] After a fracture, the periosteal vessels bleed around the defect, forming clots around the bone fragments. The osteoblasts multiply within two days, allowing cambium expansion and forms callus. Osteoblastic differentiation instigates bone growth between the fracture ends. Traumatic hematoma leads to the rapid multiplication of endosteal cells, aiding in ostial solidification, and rebuilding a bridge of reparatory callus.[12][35][36]

- Bone modeling and remodeling: Periosteum, endosteum, and its cells play a critical role in modeling and remodeling.

- Bone remodeling is a process where osteoclasts and osteoblasts work sequentially to reshape and renew bone; the process continues throughout life. It divides into four phases; (a) recruitment and activation of osteoclasts, (b) resorption of old bony tissue, (c) apoptosis of osteoclasts, and activation of osteoblasts (d) laying of new organic matrix and mineralization.[37][38][39]

- Bone modeling is a process to shape the bone during growth, development, and healing. Mechanical factors like stress, strain, tension, muscular attachment, etc. play an important role in bone modeling. Osteoblasts and osteoclast play an independent role in bone modeling.[37][11][37]

- Calcium Homeostasis: Endosteum plays a role in the deposition of calcium in the matrix; as well, it is a medium for the transfer of calcium between the bony matrix and blood.[32][16][31]

- The periosteum is a medium for the attachment of muscles, tendons, and ligaments to the bone. Tendon fibers perforate the outer layer of the periosteum and continue as the perforating fibers of Sharpey.[40][41][42]

- Limiting membrane: Periosteum appears to prevent spilling out of the osseous tissue so also known as limiting membrane.[14][12][15][43]

Tissue Preparation

Ground Section of the Bone: Traditionally, the ground section is used to observe the histology of the bone without staining. In the ground section, the bone can be examined histologically without calcification.

- Steps for the ground section of the bone: The specimen is placed 20% formalin solution for 24 hours, washed with tap water. The bone is sectioned to the desired thickness by any of the following methods. 1. Ultramicrotome with a diamond cutting blade. 2. Grinding with burr from both sides. 3. Hand grinding using a carborundum stone. A continuous spray of water and Paris powder is recommended while grinding the tissue to avoid damage to the histology of the tissue.

- Advantage of the Ground section method: Minimal minerals are lost during the method.

- Disadvantage: Ultrathin sections are difficult to achieve.[44]

Other Methods for Undecalcified Bone Preparation for Periosteum and Endosteum Study [45][46][47][48]:

- The specimen is put in an air-tight container with 20% phosphate-buffered formalin with minimal light exposure.

- Trim and cut the bone with a band saw according to the required size and part to be studied. The specimen should be trimmed to the adequate thickness.

- The specimen is kept in 10 to 20% formalin for two weeks.

- Shift the specimen in ascending concentration of ethanol: 1 week in 70% ethanol, one week in 80% ethanol, one week in 90% ethanol, one week in 100% ethanol.

- The specimen is cleared in butanol for one week avoiding exposure light.

- The specimen is put in a mold and embedded with a resin solution matching the density of the tissue. While embedding cutting surface of the tissue should be directed downward, hardener can be added to the resin also.

- The mold is kept overnight, a mix of two-component resin, based on methyl methacrylate (2 part powder and 1 part of the liquid) is poured in the recess to cover the base of the block. After 10 to 15 minutes, the mold can be pulled away. The prepared block should be stored in a desiccator.

- For fluoroscopic examination, a ground section of the tissue of 20 to 50-micrometer thickness is used. Ultramicrotome with a diamond blade is used to section the block.

- Mounting the section: carefully selected sections taken on the slide and kept in the incubator at 60 to 80 degrees Celsius for one hour.; section adheres to the slide and can be used after cleaning and polishing.

- The staining methods can also be used like hematoxylin and eosin, Von Kossa staining method, Masson Goldner's Trichrome.

- Tissue can be processed for fluorochrome examination.

Phenotypic properties of the human periosteum and the distribution of the cells within various strata are observable with immunohistochemical staining techniques and RT-PCR.

Fluoresence Microscopy [49][50][51]:

- Remove fresh periosteum by utilizing blunt forceps to protect the cambium and fibrous layers.

- Fix the periosteal sample tissue in 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for a minimum of 4 hours.

- Freeze the sample in liquid nitrogen and ascend vertically into the OCT compound of the cryosectioning.

- Take 2 to 8 micrometers thick cross-sections at 5 degrees Fahrenheit temperature. Stain the section with standard hematoxylin/eosin staining method to verify the orientation of the periosteum and to check for both the cambium and the fibrous layers.

- Immunostaining: Incubate the samples with 0.2% Triton X-100 in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at room temperature for 10 minutes.

Tartrate-resistant acidic phosphatase (TRAP) stain, Incubate cells for 15 minutes with ELF97 substrate in 110 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.2) containing 1.1 mM sodium nitrite and 7.4 mM tartrate (Sigma Aldrich).[51][49]

For Decalcified Bone [52][53][54]:

Light Microscopy:

- Immerse bone specimen in 2% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde for two weeks.

- Decalcify in 7% with 0.5 % paraformaldehyde for 35 to 50 days.

- Embed the tissue in paraffin; cut 2 to 3-micrometers-thick sections with an ultramicrotome. Take the selected section on glass slides and rehydrate through a series of graded alcohol concentration.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

- Cut the tissue into small samples (approximately1 mm)

- Fix into 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% gluteradehyde.

- Embed in the acrylate- and methacrylate-based resin Lowicryl HM23 with descending temperature according to standard protocol.

Histochemistry and Cytochemistry

Rehydrate sections in descending concentration of alcohol solution.

Haematoxylin and Eosin [45][48]:

- Place the rehydrated section on a slide.

- Stain with standard Haemotoxylin for 5 to 10 minutes.

- Wash with tap water for 4 to 5 minutes.

- Stain with Eosin for 5 minutes.

- Wash in tap water.

- Mount and observe in a microscope.

- Results: Osteoid looks pink; calcified bone looks purplish brown, nuclei look blue.

Von Kossa staining (Chemical Mechanisms of Staining Methods: Von Kossa's Technique) [55][45]:

- Put the section in silver nitrate solution approximately for at least 10 minutes under strong light; the section should be turned black.

- Wash with distilled water for 3 to 5 times and then treat put in sodium thiosulfate for 4 to 6 minutes.

- Wash with distilled water for 1 to 2 minutes then counterstain with safranin O.

- Clear with xylene and mount on the glass slide.

- Mineralized bone looks black with red to pink osteoids.

Masson Goldner's Trichrome [45][56][57][58][59]:

- Use alkaline alcohol (90 ml 80% ethanol mixed with 10mls 25% ammonia) to wash the section then rinse with tap water.

- Wash with distilled water

- Stain with Weigert s Haematoxylin for 10 minutes

- Wash with distilled water

- Wash with 1% acetic acid for 20 to 30 seconds

- Stain with reagent 1, e.g., stain with Ponceau-Fuchsin final solution 5 minutes

- Wash with 1% acetic acid for 20 to 30 seconds

- Stain with reagent 2, e.g., phosphomolybdic acid-orange G solution for 5 minutes

- Wash with 1% acetic acid for 20 to 30 seconds

- Stain with Reagent 3 e.g., light green for 5 minutes

- Wash with 1% acetic acid for 20 to 30 seconds

- Wash with distilled water

- Mount with non-aqueous mounting media

- Mineralized bone looks green, osteoid looks orange or red, nuclei look blue-grey, and cartilage looks purple.

Immunohistochemical Staining and Fluorescence Microscopy [51][60][61]:

- Incubate cells for 15 mins in acetate buffer (110mM, pH 5.2) for 14-16 minutes ELF97 substrate. Stain nuclei with DAPI (4′,6-diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride, 10 ng/mL)

- Antibody for the desired epitope can be used for immunohistochemical staining e.g., Stro-1, alkaline phosphatase, vimentin, MHC Class-II, CD3, core-binding factor alpha-1.

- Mount the stained section in fluorescence mounting medium; study the section under a confocal microscope.

Recombinant DNA produced via coating formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded PCL/PLLA specimens with PLLA nanofibers can be used to demonstrate the inner chemistry of the periosteum.

Mayer's hematoxylin counterstain helps to mark cells underlying PCL/PLLA scaffold, within the periosteum, and layers of PLLA nanofibers. (PCL=polycaprolactone-co-lactide ) Calcium is stained with alizarin red stain and is visible at the interface between the PCL/PLLA inner scaffold. Phosphate, marked with a black stain by von Kossa treatment, reflects the same traits as the area stained with alizarin red.[50]

For Electron Microscopy

Fix the bone in glutaraldehyde for 2 hours. Wash the tissue using a saccharose solution overnight and postfix the sample in osmium tetroxide for about 1 hour. After dehydrating the sample with propylene oxide and alcohol, embed the sample in Epon B. Prepare thin slices and stain the sample using toluidine blue, followed by another cut using an ultramicrotome with a diamond knife to gain ultrathin samples. Use uranyl acetate to stain the ultrathin sections and lead with citrate before viewing it under the transmission electron microscope.[62]

Microscopy, Light

To prepare a compound microscopy sample, researchers cut the bone sample to approximately 25 mm in length using a saw microtome. They refine the bone using some warm water and polish the side that will touch the microscope glass slide using the grinding paper and micro-mesh polishing pad. Afterward, they clamp the entire segment in a vice and carefully make a narrow slice. They cut the section to 5mm by 5mm chip. Transparent epoxy glue is used to bind the segment to the microscope glass slide. Researchers then firmly attach the sample to the slide, using the polish paper to decrease thickness to about 25um. The dust is removed by wiping the preparation with water followed by coverslipping before final viewing under 40x magnification.[50][63][64]

Ground section compact bone (Image 1,2): lamellar organization of Boston with Haversian canal is visible in the horizontal section of the bone. At the outer surface thin layer of the periosteum can be seen. Two layers of the periosteum are difficult to differentiate in the ground section. In many cases, periosteum may also be lost if not properly preserved. Endosteum is visible as the lining membrane of the osteon and the internal wall of the shaft.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain (Image 3):

The periosteum is composed of two layers: The outer firm and a fibrous layer made up of collagen and reticular fibers and an inner proliferative cambial layer.

The periosteum is identifiable on the outer surface of the bone; both layers of the periosteum can be differentiated. The outer layer provides elasticity, while the inner layer consists of three to four layers of cells.

Periosteum divides into three zones.

The first zone adjacent to the bony surface predominantly contains osteoprogenitor and osteoblast; this thinnest part of the periosteum can be named as a germinative zone.[65]

The second zone is the thickest part and transparent part of the periosteum; it contains capillaries and amorphous extracellular matrix. Fibroblast is abundant in this layer. This layer contains pericyte along with microvessels.[15] Pericytes are resting stem cells with the capability to differentiate into osteoblast; they stimulate wound healing in the fracture and can regulate the blood flow.[66][27][67] Pericyte secretes alkaline phosphatase (ALP), osteoclast marker and bony matrix, osteocalcin, osteonectin, osteopontin, and bone sialoprotein.[68] Zone I and II are collectively known as the cambium layer.

The third zone of the periosteum consists of abundant fibroblast and collagen fibers; the extracellular matrix is low in amount. The collagen fibers are firm and insoluble. This layer is also known as the fibrous layer. With the aging, collagen fibers and cells decrease, and periosteum becomes thinner.[69]

The endosteal membrane is identifiable as a membrane covering the osteonal (Haversian) canal, and Volkman's canal.

Osteoprogenitor cells are identifiable in both endosteum and deeper layer of the periosteum; In adult bone, the deeper layer of the periosteum is thinner. Osteoprogenitor cells appear flattened with light staining in growing bones. It may be acidophilic or slightly basophilic also. In the inner layer, multiple cells are visible, while in the outer layer shows fibrous structure. The bone covering is a layer of the flattened cells in sites where remodeling is not active.[27][50][27][70]

PEriosteum is anchored to osseous tissue by extended cellular processes between osteoblasts and osteocytes known as the lacuna-canalicular network. The perforating fibers also form a nail-like structure and continue with collagenous fibers of the internal matrix of the bone; these perforating fibers are known as Sharpey's fibers also keep the periosteum anchored to the bone. The other involves perforating fibers.[71]

Microscopy, Electron

The outer fibrous layer and the inner cellular layer of the periosteum is differentiated in electron micrography. The inner layer contains osteoprogenitor cells, which show the presence of rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER), free ribosomes, Golgi apparatus, and other organelles.[72][73]

The periosteal cells at inactive sites show the paucity of organelles in the extranuclear area. Gap junctions are identifiable between neighboring periosteal cells. Some workers describe these periosteal cells as derivatives of the osteoblasts. These periosteal cells have a nutritional role in the bone.[74]

Pathophysiology

Inflammation of the periosteum, periostitis, involves a dynamic pathophysiological pathway. Acute periostitis is caused by infection, which is marked by severe pain, the formation of pus, pain, constitutional symptoms, resulting in necrosis. An immoderate level of physical activity as well, as in the case of tibial periostalgia, instigates the formation of periostitis. Acute periostitis usually initiates in the deeper osteogenic layer of the periosteum by exudation and inflammation around the vessels; the periosteum unfastens and lifts from the bone by the exudation, leading to eventual destruction. This condition may lead simply to exfoliation or maybe the indication of extensive necrosis.

Periostitis involves the IL1RN (interleukin-1 receptor antagonist) gene and utilizes the innate immune system, and pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) Induced Signaling to establish its mechanisms. PEDF is a member of the serine proteinase inhibitor (serpin) family. This polypeptide is traced back to as the agent of inflammation in cases of periostitis. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) and type II interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R2) are the associated regulators of IL-1 biologic activity. During the inflammatory response, IL-1ra levels increase more than IL-1 levels, indicating that IL-1ra works to block further IL-1 activity and acts in the eventual termination of the inflammation; however, a mutation may inhibit IL-1ra activity. Individuals with this mutation either do not make or make defective, IL-1 receptor antagonists (IL-1Ra). This condition is known as DIRA (deficiency of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist), which is caused by homozygous recessive deletions of 2q13, E77X, N52KfsX25, and Q54X genes. The absence of IL-1ra results in unchallenged signaling through the IL-1R, leading to hyperactivity of cells related to IL-1-alpha and IL-1-beta with overproduction of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The malfunctioning of the IL-1 pathway yields systemic inflammation. Osteomyelitis may show a correlation with periostitis; however, misassociation has persisted in the past due to similar symptoms. Acute periostitis seldom affects the joints and may lead to the destruction of the medulla without acute inflammation. Congenital infection with syphilis may also lead to periostitis in newborn infants.[75][76][77][78]

Endosteal hyperostosis is an autosomal dominant sclerosing bone disorder marked by skeletal densification. This condition is common in the tubular long bones and the cranial vault without a prominent risk of fracture. The syndrome results from a mutation in the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-5 (LRP5) gene that yields increased bone formation. G171V mutation in the LPR5 was identified as the sub-mechanism. It can be distinguished from VBD and sclerostosis via a more harmless clinical presentation, although the radiological analysis may overlap.[79]

Clinical Significance

Cartilage repair: Cambium layer (deep layer) of the periosteum contains multipotent stem cells that can differentiate in both osteoblasts as well as chondroblasts. The periosteal graft can help to repair the articular cartilage defect.[65][51][80][51]

Bone repair: The periosteum is also used to repair a bone defect; the fibula is one of the common bone used for bone grafting. Various reconstructive surgical procedures now require autologous periosteum for repairing lost tissues.[81][82]

Periosteal grafts and periosteal stripping can be used in limb equalizing procedures in patients with limb length discrepancies.[83][84][85]

Periosteum plays a significant role in the recovery from orthopedic and invasive dental procedures. [86][87][30]

Excessive periosteal generation contributes to Paget’s disease. A heterogeneous region of osteosclerotic bone models in precincts of the formerly pure osteolytic skeleton. Long bones and patchy sclerosis that superimposes on earlier osteolytic processes directly show this development. Over time, bone traits may evolve into a dominant osteosclerotic appearance. The appearance is coordinated with periosteal new bone formation, increasing bone circumference.[30][88]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bicalho E. The Intraosseous Dysfunction in the Osteopathic Perspective: Mechanisms Implicating the Bone Tissue. Cureus. 2020 Jan 24:12(1):e6760. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6760. Epub 2020 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 32140328]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFischer C. [General fracture principles and imaging characteristics]. Der Radiologe. 2020 Jun:60(6):477-486. doi: 10.1007/s00117-020-00694-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32415316]

Flis M, Gugała D, Muszyński S, Dobrowolski P, Kwiecień M, Grela ER, Tomaszewska E. The Influence of the Partial Replacing of Inorganic Salts of Calcium, Zinc, Iron, and Copper with Amino Acid Complexes on Bone Development in Male Pheasants from Aviary Breeding. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI. 2019 May 13:9(5):. doi: 10.3390/ani9050237. Epub 2019 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 31086121]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDenisiuk M, Afsari A. Femoral Shaft Fractures. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310517]

Orlandi-Oliveras G, Nacarino-Meneses C, Koufos GD, Köhler M. Bone histology provides insights into the life history mechanisms underlying dwarfing in hipparionins. Scientific reports. 2018 Nov 21:8(1):17203. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35347-x. Epub 2018 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 30464210]

Buckwalter JA, Cooper RR. Bone structure and function. Instructional course lectures. 1987:36():27-48 [PubMed PMID: 3325555]

Vico L, van Rietbergen B, Vilayphiou N, Linossier MT, Locrelle H, Normand M, Zouch M, Gerbaix M, Bonnet N, Novikov V, Thomas T, Vassilieva G. Cortical and Trabecular Bone Microstructure Did Not Recover at Weight-Bearing Skeletal Sites and Progressively Deteriorated at Non-Weight-Bearing Sites During the Year Following International Space Station Missions. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2017 Oct:32(10):2010-2021. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3188. Epub 2017 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 28574653]

Thomas JD, Kehoe JL. Bone Nonunion. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32119272]

Henrichsen JL, Wilhem SK, Siljander MP, Kalma JJ, Karadsheh MS. Treatment of Patella Fractures. Orthopedics. 2018 Nov 1:41(6):e747-e755. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20181010-08. Epub 2018 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 30321439]

Sui Z, Sun H, Weng Y, Zhang X, Sun M, Sun R, Zhao B, Liang Z, Zhang Y, Li C, Zhang L. Quantitative proteomics analysis of deer antlerogenic periosteal cells reveals potential bioactive factors in velvet antlers. Journal of chromatography. A. 2020 Jan 4:1609():460496. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.460496. Epub 2019 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 31519406]

de Baat P, Heijboer MP, de Baat C. [Development, physiology, and cell activity of bone]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor tandheelkunde. 2005 Jul:112(7):258-63 [PubMed PMID: 16047964]

Bahney CS, Zondervan RL, Allison P, Theologis A, Ashley JW, Ahn J, Miclau T, Marcucio RS, Hankenson KD. Cellular biology of fracture healing. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2019 Jan:37(1):35-50. doi: 10.1002/jor.24170. Epub 2018 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 30370699]

Cooper KL, Oh S, Sung Y, Dasari RR, Kirschner MW, Tabin CJ. Multiple phases of chondrocyte enlargement underlie differences in skeletal proportions. Nature. 2013 Mar 21:495(7441):375-8. doi: 10.1038/nature11940. Epub 2013 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 23485973]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDwek JR. The periosteum: what is it, where is it, and what mimics it in its absence? Skeletal radiology. 2010 Apr:39(4):319-23. doi: 10.1007/s00256-009-0849-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20049593]

Squier CA, Ghoneim S, Kremenak CR. Ultrastructure of the periosteum from membrane bone. Journal of anatomy. 1990 Aug:171():233-9 [PubMed PMID: 2081707]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAllen MR, Hock JM, Burr DB. Periosteum: biology, regulation, and response to osteoporosis therapies. Bone. 2004 Nov:35(5):1003-12 [PubMed PMID: 15542024]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Souza LE, Malta TM, Kashima Haddad S, Covas DT. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Pericytes: To What Extent Are They Related? Stem cells and development. 2016 Dec 15:25(24):1843-1852 [PubMed PMID: 27702398]

Boskey AL, Posner AS. Bone structure, composition, and mineralization. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 1984 Oct:15(4):597-612 [PubMed PMID: 6387574]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDiaz-Flores L, Gutierrez R, Lopez-Alonso A, Gonzalez R, Varela H. Pericytes as a supplementary source of osteoblasts in periosteal osteogenesis. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1992 Feb:(275):280-6 [PubMed PMID: 1735226]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUddströmer L. The osteogenic capacity of tubular and membranous bone periosteum. A qualitative and quantitative experimental study in growing rabbits. Scandinavian journal of plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1978:12(3):195-205 [PubMed PMID: 368969]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBland YS, Ashhurst DE. Fetal and postnatal development of the patella, patellar tendon and suprapatella in the rabbit; changes in the distribution of the fibrillar collagens. Journal of anatomy. 1997 Apr:190 ( Pt 3)(Pt 3):327-42 [PubMed PMID: 9147220]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAper RL, Saltzman CL, Brown TD. The effect of hallux sesamoid excision on the flexor hallucis longus moment arm. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1996 Apr:(325):209-17 [PubMed PMID: 8998878]

Sims NA, Vrahnas C. Regulation of cortical and trabecular bone mass by communication between osteoblasts, osteocytes and osteoclasts. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2014 Nov 1:561():22-8. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.05.015. Epub 2014 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 24875146]

Christodoulou C, Spencer JA, Yeh SA, Turcotte R, Kokkaliaris KD, Panero R, Ramos A, Guo G, Seyedhassantehrani N, Esipova TV, Vinogradov SA, Rudzinskas S, Zhang Y, Perkins AS, Orkin SH, Calogero RA, Schroeder T, Lin CP, Camargo FD. Live-animal imaging of native haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nature. 2020 Feb:578(7794):278-283. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1971-z. Epub 2020 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 32025033]

Hage IS, Hamade RF. Intracortical stiffness of mid-diaphysis femur bovine bone: lacunar-canalicular based homogenization numerical solutions and microhardness measurements. Journal of materials science. Materials in medicine. 2017 Sep:28(9):135. doi: 10.1007/s10856-017-5924-5. Epub 2017 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 28762142]

Lu X, Jerban S, Wan L, Ma Y, Jang H, Le N, Yang W, Chang EY, Du J. Three-dimensional ultrashort echo time imaging with tricomponent analysis for human cortical bone. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2019 Jul:82(1):348-355. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27718. Epub 2019 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 30847989]

He X, Bougioukli S, Ortega B, Arevalo E, Lieberman JR, McMahon AP. Sox9 positive periosteal cells in fracture repair of the adult mammalian long bone. Bone. 2017 Oct:103():12-19. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2017.06.008. Epub 2017 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 28627474]

Ren L, Yang P, Wang Z, Zhang J, Ding C, Shang P. Biomechanical and biophysical environment of bone from the macroscopic to the pericellular and molecular level. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2015 Oct:50():104-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.04.021. Epub 2015 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 26119589]

Zhou X, von der Mark K, Henry S, Norton W, Adams H, de Crombrugghe B. Chondrocytes transdifferentiate into osteoblasts in endochondral bone during development, postnatal growth and fracture healing in mice. PLoS genetics. 2014 Dec:10(12):e1004820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004820. Epub 2014 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 25474590]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSzabó A, Janovszky Á, Pócs L, Boros M. The periosteal microcirculation in health and disease: An update on clinical significance. Microvascular research. 2017 Mar:110():5-13. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2016.11.005. Epub 2016 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 27889558]

Buckwalter JA, Glimcher MJ, Cooper RR, Recker R. Bone biology. I: Structure, blood supply, cells, matrix, and mineralization. Instructional course lectures. 1996:45():371-86 [PubMed PMID: 8727757]

Datta HK, Ng WF, Walker JA, Tuck SP, Varanasi SS. The cell biology of bone metabolism. Journal of clinical pathology. 2008 May:61(5):577-87. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.048868. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18441154]

Grover K, Lin L, Hu M, Muir J, Qin YX. Spatial distribution and remodeling of elastic modulus of bone in micro-regime as prediction of early stage osteoporosis. Journal of biomechanics. 2016 Jan 25:49(2):161-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.11.052. Epub 2015 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 26705110]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChoudry UH, Bakri K, Moran SL, Karacor Z, Shin AY. The vascularized medial femoral condyle periosteal bone flap for the treatment of recalcitrant bony nonunions. Annals of plastic surgery. 2008 Feb:60(2):174-80. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318056d6b5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18216511]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGorter EA, Gerretsen BM, Krijnen P, Appelman-Dijkstra NM, Schipper IB. Does osteoporosis affect the healing of subcapital humerus and distal radius fractures? Journal of orthopaedics. 2020 Nov-Dec:22():237-241. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2020.05.004. Epub 2020 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 32425424]

Szelerski Ł, Żarek S, Górski R, Mochocki K, Górski R, Morasiewicz P, Małdyk P. Surgical treatment outcomes of the Ilizarov and internal osteosynthesis methods in posttraumatic pseudarthrosis of the tibia-a retrospective comparative analysis. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2020 May 19:15(1):179. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01697-4. Epub 2020 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 32430044]

Langdahl B, Ferrari S, Dempster DW. Bone modeling and remodeling: potential as therapeutic targets for the treatment of osteoporosis. Therapeutic advances in musculoskeletal disease. 2016 Dec:8(6):225-235. doi: 10.1177/1759720X16670154. Epub 2016 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 28255336]

Manolagas SC. Birth and death of bone cells: basic regulatory mechanisms and implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoporosis. Endocrine reviews. 2000 Apr:21(2):115-37 [PubMed PMID: 10782361]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEriksen EF. Normal and pathological remodeling of human trabecular bone: three dimensional reconstruction of the remodeling sequence in normals and in metabolic bone disease. Endocrine reviews. 1986 Nov:7(4):379-408 [PubMed PMID: 3536460]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceClark J, Stechschulte DJ Jr. The interface between bone and tendon at an insertion site: a study of the quadriceps tendon insertion. Journal of anatomy. 1998 May:192 ( Pt 4)(Pt 4):605-16 [PubMed PMID: 9723987]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTabuchi K, Soejima T, Kanazawa T, Noguchi K, Nagata K. Chronological changes in the collagen-type composition at tendon-bone interface in rabbits. Bone & joint research. 2012 Sep:1(9):218-24. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.19.2000109. Epub 2012 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 23610694]

Strocchi R, Raspanti M, Ruggeri A, Franchi M, De Pasquale V, Stringa L, Ruggeri A. Intertwined Sharpey fibers in human acellular cementum. Italian journal of anatomy and embryology = Archivio italiano di anatomia ed embriologia. 1999 Oct-Dec:104(4):175-83 [PubMed PMID: 10684181]

Daley ELH, Kuttig J, Stegemann JP. Development of Modular, Dual-Perfused Osteochondral Constructs for Cartilage Repair. Tissue engineering. Part C, Methods. 2019 Mar:25(3):127-136. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2018.0356. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30724134]

Cheng ZL, Cai M, Chen XY, Li P, Chen XH, Lin ZM, Xu M. A novel cutting machine supports dental students to study the histology of the tooth hard tissue. Journal of dental sciences. 2019 Jun:14(2):113-118. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2019.03.012. Epub 2019 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 31210885]

Goldschlager T, Abdelkader A, Kerr J, Boundy I, Jenkin G. Undecalcified bone preparation for histology, histomorphometry and fluorochrome analysis. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2010 Jan 8:(35):. pii: 1707. doi: 10.3791/1707. Epub 2010 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 20062000]

Mohsin S, O' Brien FJ, Lee TC. New embedding medium for sectioning undecalcified bone. Biotechnic & histochemistry : official publication of the Biological Stain Commission. 2006 Mar-Jun:81(2-3):99-103 [PubMed PMID: 16908434]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYang R, Davies CM, Archer CW, Richards RG. Immunohistochemistry of matrix markers in Technovit 9100 New-embedded undecalcified bone sections. European cells & materials. 2003 Dec 31:6():57-71; discussion 71 [PubMed PMID: 14722903]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCano-Sánchez J, Campo-Trapero J, Gonzalo-Lafuente JC, Moreno-López LA, Bascones-Martínez A. Undecalcified bone samples: a description of the technique and its utility based on the literature. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 2005 Apr 1:10 Suppl 1():E74-87 [PubMed PMID: 15800470]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKiani MT, Takzare N, Khoshzaban A, Jalilianfar E, Aghajanpour L, Tabrizi R. Histological Changes in the Periosteum Following Subperiosteal Expansion in Rabbit Scalp. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2018 Apr:76(4):900-904. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2017.08.020. Epub 2017 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 28911959]

McClellan P, Jacquet R, Yu Q, Landis WJ. A Method for the Immunohistochemical Identification and Localization of Osterix in Periosteum-Wrapped Constructs for Tissue Engineering of Bone. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 2017 Jul:65(7):407-420. doi: 10.1369/0022155417705300. Epub 2017 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 28415912]

Frey SP, Jansen H, Doht S, Filgueira L, Zellweger R. Immunohistochemical and molecular characterization of the human periosteum. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2013:2013():341078. doi: 10.1155/2013/341078. Epub 2013 May 2 [PubMed PMID: 23737713]

Melhus G, Solberg LB, Dimmen S, Madsen JE, Nordsletten L, Reinholt FP. Experimental osteoporosis induced by ovariectomy and vitamin D deficiency does not markedly affect fracture healing in rats. Acta orthopaedica. 2007 Jun:78(3):393-403 [PubMed PMID: 17611855]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHultenby K, Reinholt FP, Oldberg A, Heinegård D. Ultrastructural immunolocalization of osteopontin in metaphyseal and cortical bone. Matrix (Stuttgart, Germany). 1991 Jun:11(3):206-13 [PubMed PMID: 1870452]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLi M, Amizuka N, Oda K, Tokunaga K, Ito T, Takeuchi K, Takagi R, Maeda T. Histochemical evidence of the initial chondrogenesis and osteogenesis in the periosteum of a rib fractured model: implications of osteocyte involvement in periosteal chondrogenesis. Microscopy research and technique. 2004 Jul 1:64(4):330-42 [PubMed PMID: 15481050]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLong PH, Tarpley JE, Rowland GN, Lee SR, Britton WM. A simple procedure for preparing and staining undecalcified sections of avian growth plate and metaphysis. Avian diseases. 1984 Jan-Mar:28(1):285-8 [PubMed PMID: 6372780]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGOMORI G. A rapid one-step trichrome stain. American journal of clinical pathology. 1950 Jul:20(7):661-4 [PubMed PMID: 15432364]

Rentsch C, Schneiders W, Manthey S, Rentsch B, Rammelt S. Comprehensive histological evaluation of bone implants. Biomatter. 2014:4():. doi: 10.4161/biom.27993. Epub 2014 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 24504113]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGruber HE. Adaptations of Goldner's Masson trichrome stain for the study of undecalcified plastic embedded bone. Biotechnic & histochemistry : official publication of the Biological Stain Commission. 1992 Jan:67(1):30-4 [PubMed PMID: 1617000]

SANO ME. Trichrome stain for tissue section, culture or smear. American journal of clinical pathology. 1949 Sep:19(9):898 [PubMed PMID: 18137790]

Filgueira L. Fluorescence-based staining for tartrate-resistant acidic phosphatase (TRAP) in osteoclasts combined with other fluorescent dyes and protocols. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 2004 Mar:52(3):411-4 [PubMed PMID: 14966208]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMeagher J, Zellweger R, Filgueira L. Functional dissociation of the basolateral transcytotic compartment from the apical phago-lysosomal compartment in human osteoclasts. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 2005 May:53(5):665-70 [PubMed PMID: 15872059]

Miller SC, Bowman BM, Smith JM, Jee WS. Characterization of endosteal bone-lining cells from fatty marrow bone sites in adult beagles. The Anatomical record. 1980 Oct:198(2):163-73 [PubMed PMID: 7212302]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBisseret D,Kaci R,Lafage-Proust MH,Alison M,Parlier-Cuau C,Laredo JD,Bousson V, Periosteum: characteristic imaging findings with emphasis on radiologic-pathologic comparisons. Skeletal radiology. 2015 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 25269751]

Kim JN, Lee JY, Shin KJ, Gil YC, Koh KS, Song WC. Haversian system of compact bone and comparison between endosteal and periosteal sides using three-dimensional reconstruction in rat. Anatomy & cell biology. 2015 Dec:48(4):258-61. doi: 10.5115/acb.2015.48.4.258. Epub 2015 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 26770876]

Simon TM, Van Sickle DC, Kunishima DH, Jackson DW. Cambium cell stimulation from surgical release of the periosteum. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2003 May:21(3):470-80 [PubMed PMID: 12706020]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYu PK, Balaratnasingam C, Cringle SJ, McAllister IL, Provis J, Yu DY. Microstructure and network organization of the microvasculature in the human macula. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2010 Dec:51(12):6735-43. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5415. Epub 2010 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 20688746]

Crocker DJ, Murad TM, Geer JC. Role of the pericyte in wound healing. An ultrastructural study. Experimental and molecular pathology. 1970 Aug:13(1):51-65 [PubMed PMID: 5459855]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDíaz-Flores L, Gutiérrez R, Madrid JF, Varela H, Valladares F, Acosta E, Martín-Vasallo P, Díaz-Flores L Jr. Pericytes. Morphofunction, interactions and pathology in a quiescent and activated mesenchymal cell niche. Histology and histopathology. 2009 Jul:24(7):909-69. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.909. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19475537]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTonna EA, Cronkite EP. The periosteum. Autoradiographic studies on cellular proliferation and transformation utilizing tritiated thymidine. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1963:30():218-33 [PubMed PMID: 4172521]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRoberto-Rodrigues M, Fernandes RM, Senos R, Scoralick AC, Bastos AL, Santos TM, Viana LP, Lima I, Guzman-Silva MA, Kfoury-Júnior JR. Novel rat model of nonunion fracture with vascular deficit. Injury. 2015 Apr:46(4):649-54. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.01.033. Epub 2015 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 25661107]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHirashima S, Ohta K, Kanazawa T, Uemura K, Togo A, Yoshitomi M, Okayama S, Kusukawa J, Nakamura K. Anchoring structure of the calvarial periosteum revealed by focused ion beam/scanning electron microscope tomography. Scientific reports. 2015 Dec 2:5():17511. doi: 10.1038/srep17511. Epub 2015 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 26627533]

Danalache M, Kliesch SM, Munz M, Naros A, Reinert S, Alexander D. Quality Analysis of Minerals Formed by Jaw Periosteal Cells under Different Culture Conditions. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 Aug 27:20(17):. doi: 10.3390/ijms20174193. Epub 2019 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 31461878]

Liu C, Cabahug-Zuckerman P, Stubbs C, Pendola M, Cai C, Mann KA, Castillo AB. Mechanical Loading Promotes the Expansion of Primitive Osteoprogenitors and Organizes Matrix and Vascular Morphology in Long Bone Defects. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2019 May:34(5):896-910. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3668. Epub 2019 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 30645780]

Boyde A, Hordell MH. Scanning electron microscopy of lamellar bone. Zeitschrift fur Zellforschung und mikroskopische Anatomie (Vienna, Austria : 1948). 1969:93(2):213-31 [PubMed PMID: 4905350]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHe X, Cheng R, Benyajati S, Ma JX. PEDF and its roles in physiological and pathological conditions: implication in diabetic and hypoxia-induced angiogenic diseases. Clinical science (London, England : 1979). 2015 Jun:128(11):805-23. doi: 10.1042/CS20130463. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25881671]

Famulla S, Lamers D, Hartwig S, Passlack W, Horrighs A, Cramer A, Lehr S, Sell H, Eckel J. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) is one of the most abundant proteins secreted by human adipocytes and induces insulin resistance and inflammatory signaling in muscle and fat cells. International journal of obesity (2005). 2011 Jun:35(6):762-72. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.212. Epub 2010 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 20938440]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBeck C, Girschick HJ, Morbach H, Schwarz T, Yimam T, Frenkel J, van Gijn ME. Mutation screening of the IL-1 receptor antagonist gene in chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis of childhood and adolescence. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2011 Nov-Dec:29(6):1040-3 [PubMed PMID: 22032624]

Schnellbacher C, Ciocca G, Menendez R, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R, Duarte AM, Rivas-Chacon R. Deficiency of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist responsive to anakinra. Pediatric dermatology. 2013 Nov-Dec:30(6):758-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01725.x. Epub 2012 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 22471702]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVan Wesenbeeck L, Cleiren E, Gram J, Beals RK, Bénichou O, Scopelliti D, Key L, Renton T, Bartels C, Gong Y, Warman ML, De Vernejoul MC, Bollerslev J, Van Hul W. Six novel missense mutations in the LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) gene in different conditions with an increased bone density. American journal of human genetics. 2003 Mar:72(3):763-71 [PubMed PMID: 12579474]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceO'Driscoll SW. Articular cartilage regeneration using periosteum. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1999 Oct:(367 Suppl):S186-203 [PubMed PMID: 10546647]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen D, Shen H, Shao J, Jiang Y, Lu J, He Y, Huang C. Superior mineralization and neovascularization capacity of adult human metaphyseal periosteum-derived cells for skeletal tissue engineering applications. International journal of molecular medicine. 2011 May:27(5):707-13. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.634. Epub 2011 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 21369695]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGamie Z, Tran GT, Vyzas G, Korres N, Heliotis M, Mantalaris A, Tsiridis E. Stem cells combined with bone graft substitutes in skeletal tissue engineering. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2012 Jun:12(6):713-29. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.679652. Epub 2012 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 22500826]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBurnei G, Vlad C, Gavriliu S, Georgescu I, Hodorogea D, Pârvan A, Burnei C, El Nayef T, Drăghici I. Upper and lower limb length equalization: diagnosis, limb lengthening and curtailment, epiphysiodesis. Romanian journal of internal medicine = Revue roumaine de medecine interne. 2012 Jan-Mar:50(1):43-59 [PubMed PMID: 22788093]

Limpaphayom N, Prasongchin P. Surgical technique: Lower limb-length equalization by periosteal stripping and periosteal division. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2011 Nov:469(11):3181-9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2013-9. Epub 2011 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 21830168]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEdwards DJ, Bickerstaff DB, Bell MJ. Periosteal stripping in achondroplastic children. Little effect on limb length in 10 cases. Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1994 Jun:65(3):333-4 [PubMed PMID: 8042489]

Wei H, Li S, Wei R, Chen Y. [Free fibula flap and computed tomographic angiography in the functional reconstruction of oral and maxillofacial hard and soft tissue defects]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology, head, and neck surgery. 2014 Aug:28(16):1248-50 [PubMed PMID: 25464569]

Abed PF, El Chaar E, Boltchi F, Bassir SH. The Novel Periosteal Flap Stretch Technique: A Predictable Method to Achieve and maintain Primary Closure in Augmentative Procedures. Journal of the International Academy of Periodontology. 2020 Jan 1:22(1):11-20 [PubMed PMID: 31896103]

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Singer FR. Paget’s Disease of Bone. Endotext. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 25905262]